This is the third and final part of an ExportNZ paper commissioned from the NZIER. (Part I is here. Part II is here.)

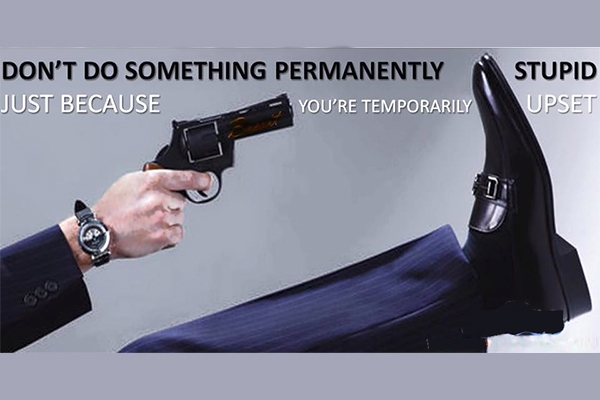

Imposing trade barriers to support job growth is like shooting yourself in the foot

There is little economic logic behind the idea that higher trade barriers will support domestic employment and living standards in the long run.

Protectionism may well ‘save’ jobs in some sectors, but this comes at a cost. There are no free lunches. These workers can no longer be employed in more internationally competitive sectors. This suppresses an economy’s productivity and hence overall wage growth. And tariffs and other trade barriers push up the cost of living, which further exacerbates the negative impacts on households, especially poorer households.

By way of example, Donald Trump has threatened to impose huge tariffs on Chinese and Mexican imports on the basis that they are ‘unfairly’ displacing US domestic manufacturing production. One estimate is that such policies could result in the loss of up to 4.8 million US jobs.1

As we have previously noted, if isolationism from the global economy was the recipe for economic success, then North Korea would be the poster-child.2

Investment rather than protection is the key for helping these industries to adjust

The negative impacts on employment from deeper regional economic integration should not be dismissed out of hand. These costs are real, and can be painful for those displaced. New Zealand workers experienced such challenges in the post-reform period in the 1980s as previously protected sectors such as automobile production and assembly and apparel production – and even farmers – were exposed to greater international competition.

Governments need to do all they can to prepare workers for such changes through greater investment in foundation education and skills and vocational training.3 They should also provide short-term assistance when alternative employment is not readily available.

But these costs also need to be weighed up against the very real benefits that households and firms gain from globalisation and trade liberalisation.

Trade agreements now have impacts beyond goods exports and imports…

This changing [trade] landscape brings challenges. The beneficiaries of trade policies and the bearers of costs from barriers are becoming more diffuse than what they once were. There is a less vocal and identifiable constituency for reducing behind the border barriers or pursuing further economic integration than, say, reforming agricultural tariffs and subsidies.4

Another reason why trade liberalisation’s reputation has been dented in recent times is because of the changing nature of trade agreements. Modern trade agreements have extended well beyond the border (i.e. tariffs and quotas) and now commonly incorporate provisions that aim to regulate trans-national flows of people, intellectual property and investment, for example.

This has made many people wary about how they as individuals or households might be affected by FTAs. The recent TPP public debate rarely centred on market access provisions for our exporters or the extent to which New Zealand would have to lower its tariffs.5 Rather, the main concerns in New Zealand were about the ability of foreign firms to influence New Zealand’s regulatory settings such as the plain packaging of cigarettes, and the potential impacts of the intellectual property provisions on the costs of medicines.

…which means better evidence of the net benefits of trade liberalisation are required

The consensus that trade makes the world richer; the tolerance that lets millions move in search of opportunities; the ideal that people of different hues and faiths can get along—all are under threat. A world of national fortresses will be poorer and gloomier.6

While most of these concerns were overblown7, based on out of date negotiating positions or only marginally relevant precedent agreements, and fuelled by overseas social media commentators, they nevertheless highlighted a sea change in the way that the public engages with trade issues.

Members of the public want to know – and rightly so – what trade liberalisation and deeper economic integration will mean for their everyday lives. Many Kiwis won’t care about how many additional tonnes of quota access New Zealand gains from an FTA; they will care if the cost of their Netflix subscription rises or their prescription costs jump.

In our view, the further that regulatory changes from FTAs extend back towards households (e.g. IP, medicines, sentiment around sovereignty), the tighter the supporting analysis needs to be to demonstrate the benefits of these changes to households, not to firms. Researchers and policymakers need to step up the mark here.

This will be challenging because establishing the ‘right’ answer about the balance and distribution of costs and benefits is more difficult with behind-the-border regulatory changes. The net effects across stakeholder groups are more uncertain. But the work needs to be done, reviewed, refined and updated to ensure that officials and politicians have the necessary evidence to hand to explain the wider net economic benefits of further trade liberalisation.

There are plenty of areas of the ‘new’ trade policy that warrant further analysis

Some initial areas to explore with further quantitative analysis might include:

- What are the benefits to Kiwi producers of creative arts from longer copyright terms (as was envisaged by TPP)?

- How do these compare to the additional costs that might be imposed on libraries and other users of such goods and services?

- How might New Zealand’s services sectors benefit from reduced restrictions on their ability to trade in key markets? What impact would this have on employment and wages?

- What are the benefits to New Zealand investors offshore from an investor state dispute settlement that prevents their investments being unjustifiably expropriated?

- What additional gains could be made by improving New Zealand’s trade facilitation procedures?

- How could trade-distorting non-tariff barriers be addressed through trade negotiationss, and what might the benefits be for New Zealand firms and consumers?

- What could be the cost-savings or benefits for New Zealand firms (particularly in ICT) from new rules on the digital economy (for example, around data flows or protection of source code, as envisaged by TPP)?

The potential gains from these areas of trade liberalisation and economic integration are less well-known, partly due to the challenges of modelling them with confidence. But the evidence available demonstrates that the benefits to New Zealand to services and investment liberalisation, for example, are very large.

CIE (2010) explore the potential gains from a global agreement to remove the barriers to the cross-border supply of telecommunications, professional services and international air services, and eliminate barriers on foreign direct investment. This services liberalisation would increase New Zealand’s real GDP by up to 1.6% by 2020, equivalent to around $4.8 billion or over $1,000 per person.

On trade facilitation – which is about how easy it is for exporters and imports to move their products around the global economy – the WTO estimates that a comprehensive Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) would reduce trade costs by 14.5% globally and boost global GDP by between US$345 billion and US$555 billion per year.8 The OECD finds similar impacts of the TFA: a reduction in high income economies’ trade costs of 12-13%. New Zealand-specific results are not readily available, unfortunately.

The evidence base around the potential gains from reducing harmful, trade-distorting non-tariff barriers is limited, largely because determining the severity of such measures is empirically challenging. Recent NZIER work has estimated the potential cost to New Zealand exporters of APEC economies’ non-tariff measures9 at around $8.4 billion per year. NZIER also found the average ad valorem equivalent of APEC non-tariff measures is 9.7%, compared to an average tariff of 2.9%.

One New Zealand study10 compared the gains to New Zealand from global liberalisation of tariffs compared to the gains from removing all NTMs, and found that the latter would deliver over ten times as much as the former. A more recent study11 of the potential gains to New Zealand from TPP estimated that of the $4.2 billion of benefits to New Zealand, 70% could be attributed to a reduction in NTBs.

Conclusion

Kiwis rely on goods trade every day, in numerous ways; from the clothes we wear, the coffee machines and smart phones we rely on to function efficiently, the computers we sit in front of all day, the ethnic food we enjoy, to the wide-screen TVs we binge-watch Netflix on. Trade liberalisation has made these imports cheaper, which makes our wage packets go further, and has given us the export earnings to fund those wage packets in the first place.

Trade supports hundreds of thousands of jobs in New Zealand, providing households with income to spend on a wide variety of imported goods and services. Trade and trade liberalisation also helps New Zealand firms become more efficient, which supports productivity growth and higher wages.

Broader notions of trade, which include services trade, investment flows, and the movement of people and technology, also deliver daily benefits for Kiwis, even though they are harder to show in a tangible sense.

We take many of these benefits for granted – trade is as much part of the New Zealand way of life as watching the All Blacks win or enjoying a pavlova on Christmas Day. But we shouldn’t.

At a time when there are increasingly vocal concerns overseas – and to a lesser extent in New Zealand – about how trade and globalisation affect households, it is important to remind ourselves of how we all benefit from New Zealand being integrated with the global economy. When parts of the community raise concerns about the potential downsides of becoming further integrated, those concerns need to be calmly heard and responded to.

The costs of the alternatives need to be pointed out too. A deeper trading relationship with the world will make us better off; more protectionist alternatives would impose costs across the economy that would cause our living standards to deteriorate.

With a nod to Churchill, the inherent vice of globalisation is the unequal sharing of blessings; the inherent virtue of isolationism is the equal sharing of miseries.

Notes:

[1] Peterson Institute for International Economics. 2016. ‘Assessing Trade Agendas in the US Presidential Campaign’. PIIE Briefing, September 2016. https://piie.com/system/files/documents/piieb16-6.pdf

[2] NZIER. 2016. ‘Trumponomics; Risks to the New Zealand economy’. NZIER Insight 64/2016. http://nzier.org.nz/static/media/filer_public/f7/f9/f7f9becf-8dbf-459f-a207-adf442e14599/nzier_insight_65-trumponomics.pdf

[3] The Labour Party’s ‘Future of Work’ programme touches usefully on many of these issues, albeit primarily with a focus on the dislocation that may occur through further automation in the workplace.

[4] NZIER 2013, ibid.

[5] This is partly because New Zealand has very few tariffs to lower, and those that are in place are little more than negotiating coin rather than genuine industry protection measures.

[6] http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21702748-new-divide-rich-countries-not-between-left-and-right-between-open-and?frsc=dg%7Cc

[7] See https://nzier.org.nz/static/media/filer_public/bc/21/bc21a5b2-3a6b-4ba2-8cf7-2f90fd5c6909/isds_and_sovereignty.pdf for a discussion on the controversial investor state dispute settlement provisions of FTAs.

[8] WTO. 2015. ‘World Trade Report 2015: Speeding up trade: benefits and challenges of implementing the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement’. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/wtr15_e.htm

[9] Note that non-tariff measures include ‘legitimate’ measures as well as more protectionist barriers. See NZIER. 2016. ‘Quantifying the costs of non-tariff measures in the Asia-Pacific region: Initial estimates’. NZIER Public Good Working paper 2016/4, November 2016. http://nzier.org.nz/static/media/filer_public/51/5f/515f28b2-4c78-41f3-a908-5638613e10d8/wp2016-4_non-tariff_measures_in_apec.pdf

[10] Winchester, N. 2008.’ Is there a dirty little secret? Non-tariff barriers and the gains from trade’. University of Otago Economics Discussion Papers, No. 0801, January 2008. http://www.otago.ac.nz/economics/research/otago077106.pdf

[11] A Strutt, P. Minor and A. Rae. 2015. ‘A Dynamic Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) Analysis of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Potential Impacts on the New Zealand Economy’. Report to MFAT, September 2015. Note that the benefits figures used in the government’s communications were somewhat lower than this – see https://tpp.mfat.govt.nz/assets/docs/TPP%20-%20CGE%20Analysis%20of%20Impact%20on%20New%20Zealand,%20explanatory%20cover%20note.pdf

This is the third part of an ExportNZ paper commissioned from the NZIER. Part I is here. Part II is here. The full Report is available here. This article is here with permission.

16 Comments

Once over lightly yet again. He sets up weak arguments that folk are not making - like isolationism per North Korea and then knocks them about. Not difficult.

But he ignores other things. The issues are about more than jobs for the worker ants.

As before from part one "..........Seems to me an important component of globalisation is ownership of the enterprises, which this article ignores. Note the chinese moves into vertical integration and control within the dairy industry. That could be promoted as "trade and good", but in my view delivers as always the benefit to the owners - so bad.

Remember always what Marx says - the ultimate benefit always flows to the owner - which is why I have always tried to be the owner........."

National does not stand in the way of Kiwis who want to sell their assets to whoever they want. If Kiwis would prefer only to sell to other Kiwis, that is their business; if they are happy to sell to a foreign buyer offering a better price, that is their business as well.

How does this make the legacy for future Kiwis worse? Let's think it through.

Andrew Kiwi does not sell his farm to anybody and instead bequeaths it to his son Andrew Kiwison, who keeps it. Good for Andrew Kiwison, but how does this benefit any other Kiwi?

Bob Kiwi bequeaths his farm to Bob Kiwi Jr, who doesn't like farming but is very interested in IT. He sells the farm to Chris Kiwi and invests the money in an IT startup which enables him to make a great deal more money than he could have on the farm. He leaves the money to his son Bob Kiwi III. Bob Kiwi Jr's family and Chris Kiwi are both better off, but how does this benefit any other Kiwi?

After a few years of farming Chris Kiwi sells the farm to Dave American and retires on the money he made on the sale. Dave American makes a few investments to improve the productivity of the farm. Chris Kiwi is better off, and the NZ economy as a whole and NZ export earnings both benefit.

How does any of this affect the legacy of Ed Kiwi?

Yes, he doesn't own Dave American's farm. So what? He doesn't own Andrew Kiwi's farm either. What's the difference between him not owning a farm because Andrew Kiwi owns it, and not owning a farm because Dave American owns it? They are both equally likely (or not) to sell, and he is equally likely to be able (or not) to buy from either of them.

How is any of this improved, through what seems to be your preferred approach - not allowing Chris Kiwi to sell to Dave American?

It might improve the prospects of Ed Kiwi being able to buy a farm. But it would leave Chris Kiwi worse off; he would have to either keep the farm which he no longer wants, or to accept a lower price for it than he could have got from Dave American. And if Ed Kiwi doesn't have as much money as Dave American, he may not be able to make the investments to improve the farm's productivity, so the NZ economy as a whole is worse off and export earnings are not as high as they would have been with Dave American's involvement.

Sorry, but no. It's not obvious how allowing Kiwis to do what they want with their own property makes things worse for future Kiwis.

Big wall of text but I'd also suggest reading NZ's history, including why we ended up with land tax (not just income tax, as it's now disproportionately) targeting land banks to discourage foreign land-lordism and get more land into more average Kiwi hands. TOP's got some good ideas around rebalancing.

At the moment it's Kiwis who have to bear the brunt of funding NZ's taxes while land has been receiving a free ride - we're only going to grow mult-generational haves and have-nots, not a great outcome (except for those who were born at the right time to benefit from both earlier societal efforts and subsequent changes).

I don't have a problem particularly with a land tax; I agree that the absence of a land tax means that other taxes are higher, and that it distorts investment decisions. But I'm not sure how it is relevant to the issue of foreign ownership of property in NZ.

Why would a land tax discourage foreign land-lordism any more, or any less, than it would discourage Kiwi land-lordism?

Why would it mean land getting into average Kiwi hands any more, or any less, than it would mean land getting into average foreign hands?

I liked your farming story Ms De Meanour so I made up my own..

Bob is a farmer just like his father and his fathers father. He sells his farm to Zhang Wei (a purely fictional character) who has ties to the Chinese communist party and pays 500K more that the competing NZ bidder. The OIO approves the sale with MP’s mysteriously writing letters of support on behalf of Wei. Zhang Wei decides not to employ NZ workers but rather fly temp workers in to maintain the farm because they demand lower wages. Zhang Wei also has ties to the Yanshili processing facility in Pokeno and has the milk processed to a minimum level for export to China where it is then converted to valuable infant formula. Additional work is created in China for patent attorneys lawyers and engineers etc. who are more “competitive” than their NZ counterparts. Bob uses the money from the farm sale to buy four houses and a boat.

In a land called New Zealand the citizens owned all the farms. Owners do the best so they were very happy. In a parallel universe a guy named Tex in Texas owned all the New Zealand farms and the New Zealand citizens all worked for him. Owners do the best so Tex was very happy.

Point being MdM is that I am not a citizen of the world but of New Zealand and I am interested more in the interests of our citizens.

In a third parallel universe the New Zealand citizens owned the New Zealand farms and the farms in Texas as well and Tex worked for them. Here the New Zealand citizens were very happy.

Tex was very happy because he understood globalisation ( the cunning New Zealanders had sent over a guy call Ballingall to éducate' them.) Thanks to Mr Ballingall he was so happy to have a job and had moved into the shacks at the back of the farm with his former employees, the Mexicans.

What we also have happening in NZ are foreign investors buying forests, steel mills, electricity generation, farmland and processing the product in NZ, Then selling to associated business in homeland for a very small profit. Small profit means low tax for NZ. The associated business in homeland then sells for true value. NZ just got screwed. We are selling our productivity into foreign ownership and becoming tenants in our own land.

Ms de Menour,

Your first sentence is just plain wrong. There is such a thing as the Overseas Investment Office which vets foreign purchases(if not very well),above a certain level.

Are you really saying that you would be happy to see every NZ business owned by a foreign entity? Can you name a country that would permit that? No? I thought not.

How far would you go? What about our public services? The defence force,such as it is?

""The consensus that trade makes the world richer; the tolerance that lets millions move in search of opportunities; the ideal that people of different hues and faiths can get along—all are under threat. A world of national fortresses will be poorer and gloomier.""

Just off the top of my head: Catholic/Protestant Northern Island, Hutsi/Tutsi, Serb/Bosnian/Kosono Muslim, Turk/Armenian/Kurd, Iraqi/Kurd, Brazil's Amazon Tribes, Tibetan/Chinese, Chinese Han/Uyghurs, Mexico indigenous peoples, Baltic states and Russian minorities, Ukranians and Russian minorities, Burma and Muslim and other minorities, Philipines and their Muslims, Thailand and their Muslims, Sri Lanka civil war, Anti-Christian and Anti-Muslim activities in India, most of ex USSR central Asia, Lebanese and Syrian civil wars, 2000 years of inter-caste conflict in India, 2000 years of intermittent persecution of Jews in every country, Australia and its aborigines, England and Scotland, England and Ireland, Spain and Catalans and Basques, etc..

That's right we do all get along fine don't we...

The common feature is neither religion nor race, it is identity (ref Caste and Hutsi/Tutsi). Can people of different hues and faiths get along? YES when there is a dominant dictator (ref Ottoman Emperor, Stalin). And YES when there is a superior identity (ref all Jehovah Witnesses. In the USA at Ellis Island immigrants left their past behind and saluted their new flag). But NO when you have a democracy and it is politically advantageous to appeal to identity.

So why does this writer and the writers of the Economist who he is quoting believe otherwise (and so do most of our NZ political parties)? Because they are all identifying with their own special caste: the intellectual academic.

So globalisation is a success until you start moving and mixing people. Therefore NZ should handle immigration with care. To quote James Shaw it is a matter of values but what he doesn't realise it is a matter of getting every Kiwi and every immigrant sharing a set of common values. Just takes time and effort and avoiding the multi-cutural myth.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.