By Paul Young and Geoff Simmons*

New Zealand has so far managed to meet its international climate change commitments despite national greenhouse gas emissions rising significantly since 1990.

In our previous report, Climate Cheats, we showed that one part of New Zealand’s strategy involves huge quantities of carbon credits from Ukraine and Russia which were essentially fraudulent.

The biggest contributor towards New Zealand meeting its targets is, in fact, forestry. Specifically, the huge swathe of pine plantations established in the 1990s. As these pine forests have grown, current rules have allowed New Zealand to gain credits for all the carbon stored, covering most of the gap between our emissions and our targets.

However, when those forests begin to be harvested from around 2020, New Zealand will have to pay many of those credits back.

This report exposes a covert Government plan to change the rules and avoid paying those credits back. To understand the plan requires some understanding of forest carbon accounting.

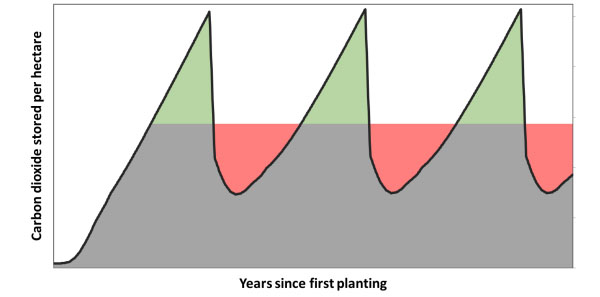

A newly planted forest soaks up carbon as it grows. If and when it is harvested, some of that carbon is returned to the atmosphere. As long as that forest is replanted, the land carbon stock never goes back to zero; there is some carbon that remains stored, fluctuating around a long-term average. As you can see in Figure 1 below, once the long-term average is reached (shaded grey), this cycle operates like a credit card with periods of carbon credit (green) and carbon debit (red).

Figure 1: Illustrative model of carbon stored by a hectare of pine plantation forestry

(The inclusion of harvested wood products complicates the picture somewhat, as the carbon stock grows over successive rotations, but this does not change the essential picture.)

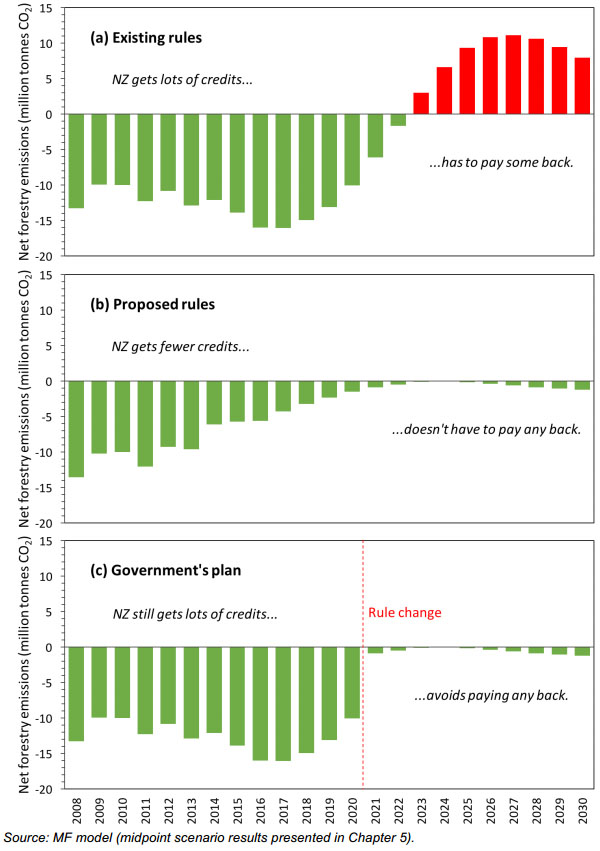

The existing rules track the cycle of carbon stored in the forest; a country receives credits as a new forest grows, but has to pay some of those back upon harvest. The pine forests planted in the 1990s will start reaching harvest age from around 2020. At that point, the forestry ‘credit card’ will be maxed out and would need to be repaid when harvesting takes off in the 2020s. This is illustrated below in Figure 2(a).

Now, the Government is proposing a new method of accounting for planted forests in our first commitment under the Paris Agreement. Under this new approach, New Zealand would only receive credits for carbon stored in a new forest up until it reaches the long term average carbon stock (the grey area in Figure 1). For a pine plantation that would be after around 20 years. If we applied this rule now, New Zealand would receive far fewer credits during the period up until 2020, but also wouldn’t have to pay any back on harvesting. This is illustrated in Figure 2(b).

The existing rules bought New Zealand time to get our greenhouse gas emissions down, but Government inaction has squandered that time. Our emissions have continued to climb in excess of our targets and it will now take a huge effort to turn things around.

The challenge for the next decade is compounded by the fact that we have to pay back some of the credits received for forests that will be harvested after 2020. What is the Government’s answer? Change the rules halfway through the game. By changing the rules in 2020, New Zealand can keep all the credits received up until then, but doesn’t have to pay any back – see Figure 2(c).

In principle, there is nothing wrong with the Government’s proposed ‘averaging approach’. The problem is the timing of the change: right when, under existing rules, New Zealand’s forestry credit card is maxed out.

Our investigation into this began with an Official Information Act request to find out the impact the proposed rule change on New Zealand’s projected emissions. The Government has refused to release this information, arguing that it would disadvantage New Zealand in the ongoing Paris Agreement negotiations. In our view, this secretive and undemocratic approach risks genuine damage to New Zealand and to the prospects of the Paris Agreement.

Given the Government’s refusal to release the information, we developed our own forestry emissions model to quantify the potential impact of the proposed rule change. Using official methodology and data inputs sourced from documents obtained through our OIA request, we are confident in the validity of our results.

Our key finding is that, up to 2020, New Zealand will claim 79 million credits (with a range of 65 to 90 million) from forests that are above their long-term average carbon stock. The harvesting or deforestation liability attached to those credits will be wiped by the rule change. The excess emissions this allows equate to nearly one year’s worth of New Zealand’s gross emissions.

Figure 2: Illustrative model of the impact of the change to averaging approach on NZ’s forestry emissions

This approach will violate not only the forest accounting rules agreed under the Kyoto Protocol, but also the Paris Agreement’s key principle of progression. Based on our model results, New Zealand’s 2030 target is not in fact a progression on our 2020 target under a consistent accounting approach. We estimate the target, under the proposed change in rules, translates to a 7% increase on 1990 levels under existing accounting rules.

If we were to also add in the 86 million surplus credits the Government seems intent on carrying over post-2020 (which it only holds due to the use of fraudulent credits bought from Ukraine and Russia), then New Zealand’s target would effectively be a 27% increase on 1990 levels.

Perhaps most damaging of all is that, to secure its preferred rules, the Government is pushing for the most flexible and non-prescriptive approach to forest accounting possible in the Paris Agreement. This negotiating stance combined with the precedent New Zealand is setting by opportunistically changing the rules could do huge damage to global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It risks opening the door for other, larger countries to similarly hide their emissions through arcane accounting tricks. And without consistent and transparent accounting, there is little hope for credible international emissions trading.

The key conclusion is that, while there appears to be some merit in the rule change the Government is proposing, integrity requires a corresponding increase in New Zealand’s 2030 target.

Firstly, the Government should front up with the information to enable the New Zealand public and the international community to engage in an honest and well-informed debate on the proposed rule change.

Secondly, the Government should increase the 2030 target by a level that would compensate for the impact of the rule change. Our analysis indicates this would require a target of at least 25-30% below 1990 levels.

Thirdly, New Zealand needs a real plan to deliver on this target and beyond. For reasons highlighted in this report, that plan should set separate gross emissions and/or sectoral targets. Storing more carbon in forests is an important part of our contribution to global climate change efforts, but it is no substitute for reducing gross emissions. To live up to the Paris Agreement, New Zealand needs a plan to get our carbon dioxide emissions down to zero in a time frame consistent with keeping global warming to well below two degrees.

Finally, the Government is yet to follow the key recommendation in Climate Cheats, to ‘dump the junk’ – commit to cancelling any surplus credits remaining as at 2020. It is especially galling for the Government to want to change to new forestry accounting rules, at the same time as attempting to carry over the proceeds of junk credits from the Kyoto Protocol’s first commitment period.

This is the Executive Summary of a paper written by Paul Young and Geoff Simmons of the Morgan Fountaion. The full paper is here. This summary is reposted with permission.

2 Comments

Cool. Well done the government. Every other government will be cheating in much more egregious ways than we ever will. New Zealand, being fairly honest, by and large, usually gets completely outwitted.

It risks opening the door for other, larger countries to similarly hide their emissions through arcane accounting tricks

The EU for instance, has the appearance of a fishing policy, but by selective policing it might as well not exist. We have a fishing policy that, whilst it is not perfect, it does actually work and we are improving as we go.

Personally, I find these agreements just as creepy as the TPP. Am I alone in this?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.