Here's my Top 10 links from around the Internet at 9.30 am in association with NZ Mint.

As always, we welcome your additions in the comments below or via email to bernard.hickey@interest.co.nz.

See all previous Top 10s here.

My must read today is #3 on the rise of the robots and challenge of falling middle class incomes. There isn't an obvious way out. #8 from Satyajit Das on Australia's problems (yes there a few) is also a cracker.

1, Now it's Cyprus' turn - The European crisis is far from over.

The next flashpoint is likely to be Cyprus, which is essentially bankrupt. It needs to restructure government debt, which would wipe out its banks, which hold most of the government debt.

So any European bailout would effectively mean bailing out the depositors in Cypriot banks, who, it turns out, are often wealthy Russians.

Rock. Meet Hard Place.

The debt isn't big enough to bring down the euro, but it will be uncomfortable.

One solution might be to sell the gas reserves just discovered off the coast of Cyprus...

Here's Reuters with an excellent analysis of the tangled web in Cyprus.

"Giving a bailout to Russian oligarchs is the worst headline you could imagine," said one EU official.That leaves the euro zone facing a conundrum. Yet there is one element that could prove decisive in the long-run and help square the circle of Cypriot debt sustainability: natural gas.

Cyprus has identified vast reserves of natural gas off its coastline, with estimates of up to 60 trillion cubic feet, with just one block in the Mediterranean basin between Cyprus and Israel estimated to contain gas worth $80 billion. The gas fields are only likely to come on line in 2018 for domestic consumption and 2019-2020 for export, but that does not prevent the future expected income being securitized.

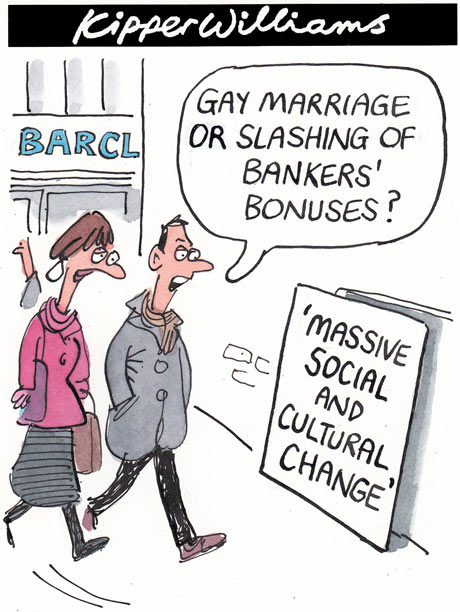

2. So what's wrong with currency wars? - The assumption widely pedalled at the moment is that 'tit for tat' currency devaluations that turn into 'currency wars' are by defnition a bad thing.

But what if they aren't?

Former Goldman economist and 'very serious person' Gavyn Davies writes in a blog at FT.com that the currency devaluations triggered at the beggining of the Great Depression by Britain's withdrawal from the Gold Standard in 1931 were only so damaging because they triggered trade controls.

What if they had just been tit for tat devaluations. Maybe not so bad, Davies says here:

In their definitive study of this episode, Barry Eichengreen and Douglas Irwin trace the slide into competitive devaluations and trade protection on a country-by-country basis, and reach a conclusion which is highly relevant to today’s currency wars. They argue that those countries which left the Gold Standard relatively early in the episode (eg the Sterling Bloc nations, which mostly left in 1931) resorted relatively less to direct trade protection through tariffs, quotas and exchange controls. Meanwhile, those countries which remained on the Gold Standard for longest (eg France and the rest of the Gold Bloc, which remained members until 1936) resorted to direct trade protection relatively more.

This is important because competitive devaluations have entirely different consequences from direct trade protection. Consider the case of a country like the UK leaving the Gold Standard and engaging in a competitive devaluation. This allowed the UK simultaneously to adopt much easier domestic monetary policies, which helped the economy to recover quickly from the recession. Other countries, like France, were net losers because the sterling devaluation switched expenditure away from French producers and towards UK producers.

The conclusion from this is that a currency war which results in tit-for-tat currency devaluations, along with monetary easing, would probably have been much less damaging than the direct trade and exchange control retaliations which actually occurred in the 1930s.

The lesson is that those who jump first win, and that those who impose trade restrictions lose. Fair enough. New Zealand looks like it will be the last to jump.

3. 'Resistance is futile' - Edward Luce writes about the 'rise of the robots' at FT.com.

During Mr Obama’s presidency, IBM’s Watson has proved computers can outfox the most agile minds, drones have become America’s weapon of choice, the driverless car is now a reality and the word “app” has been detached from its origin. No longer the realm of science fiction, the rise of robots now poses the central economic dilemma of the Obama era.

With each month, the US economy becomes steadily more automated. In January the US economy added just 4,000 manufacturing jobs, and the net increase since July is zero. Yet last month, manufacturing activity rose by its fastest rate since April, according to the Institute for Supply Management. The difference boils down to robots, which pose an increasingly nagging paradox: the more there are, the better for overall growth (since they boost productivity); yet the worse things become for the middle class. US median income has fallen in each of the last five years.

At some point, policy makers will be forced to grapple with what is intuitively obvious – that sustained growth is inconsistent with declining middle class incomes. In their book, Brynjolfsson and McAfee cite a meeting between Henry Ford and Walter Reuther, the union leader. Pointing at his new robots, Mr Ford says, “How will you get union dues from them?” Mr Reuther replied: “How will you get them to buy your cars?”

4. The bullionification of aluminium - Izabella Kaminska at FTAlphaville writes here about the dynamics in the aluminium market that seemed to have locked up a large chunk of supply in warehouses to be used as collateral in real estate deals, similar to the stockpiling seen in China for copper.

The relevance for us of course is that it shows the underlying demand and supply situation for aluminium is not good, which will all play into Rio Tinto's decision on the Bluff Smelter, which will in turn be so important for that region, for the electricity market and, ultimately, the government's State Asset sales programme.

Kaminiska is suggesting it may make sense to sell aluminium before any announcements of supply reductions...

Rather than remaining a pure consumption metal, aluminium’s attractive forward curve structure has turned it into an ideal store-and-pick-up free carry trade. That means — just like the gold market — the actual price is now determined by an ever smaller free-float on the market, despite an overall abundance of the metal above ground. Conventional inventory figures are thus becoming deceptive, since large stock no longer necessarily signals over-supply. This is because a great deal of that inventory will never really be available for market purchase.

In fact, you now have two key factors influencing price. One, is the traditional consumption rate. The other is what might be described as the “re-burying” rate — or, how quickly people can rebury (in warehouses) the aluminium that’s just been dug up, because the forward curve is paying them to do so.

Over in the aluminium market, of course, the reburying rate has not yet been over crowded. The curve, in short, is still rewarding the “reburying”. That said, if and when that curve shifts into backwardation in a meaningful and long lasting way — say because of unexpected production cuts — then we could see a similar shift as in gold. At that point it would no longer make sense to warehouse and financialise aluminium, but rather to do the opposite and to destock.

5. A corporate tax rate that ramps up as a company gets bigger - Richard Stallman, one of the guys behind Linux and the open source movement, proposes in this Reuters piece a novel way to stop companies getting so big they become too big to regulate because of their political influence. He talks about Microsoft, but he could easily have been talking about banks.

It is clear that the larger companies get, the harder it is to enforce antitrust laws against them. Yet, a business-friendly government can vitiate the law simply by launching no antitrust cases – as the Bush administration did. When the government wins such a suit, the court splits up the company to remedy the specific anti-competitive behavior proved. It can’t split the company into 50 parts just to ensure they are all small enough. We can’t fix the problem of too-big-to-fail companies this way.

I propose another method – one that can be applied to all companies. It works through taxes. There will be no need to sue companies and split them up – because they will split themselves up. The method is simple: a progressive tax on businesses. We tax a company’s gross income, with a tax rate that increases as the company gets bigger. Companies would be able to reduce their tax rates by splitting themselves up.

With this incentive, over time many companies will likely get smaller. They could subdivide in ways they consider most efficient – rather than as decided by a court. We can adjust the strength of the incentive by adjusting the tax rates. If too few companies split, we can turn up the heat.

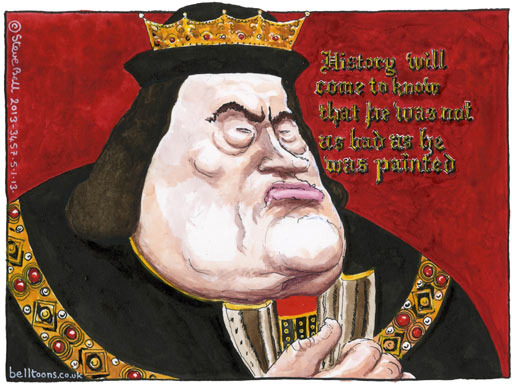

6. Japan isn't actually so bad - Paul Krugman makes an interesting point in his NYTimes blog about Japan's economic growth rate over the last couple of decades by looking at real GDP per working age person (see chart below), which strips out the effects of an ageing population, a low birth rate and little migration.

He concludes Japan did better than most people realise, but not quite enough on the monetary and fiscal side to revive the economy and return to full employment. Interestingly, overnight, the Bank of Japan Governor resigned early so the new Prime Minister Shinzo Abe can get his way. He's determined to print money to get some inflation back into the economy.

What Abenomics seems to be is an attempt, finally, to do what should have been done long ago: combine temporary fiscal stimulus with a real effort to move inflation up.

Oh, and what about the US relevance? What I think you can argue is that because we don’t share Japan’s demographic challenge, our liquidity trap is probably temporary, the product of an episode of deleveraging. So in our case fiscal stimulus is much more likely to serve as a bridge to a revived era of normal macroeconomics. That said, I welcome efforts by the Fed to modestly raise inflation expectations, and would like to see more.

So, is Japan a cautionary tale? Yes, but not the tale everyone tells. Its performance isn’t that bad given the shortage of Japanese; and it’s a tale of fiscal and monetary policy that have been too cautious, not of stimulus that failed.

7. Argentinian price freeze - BBC reports Argentina has frozen the prices of goods in supermarkets for two months. I'm no fan of this, but it's interesting to see some of the old tactics of the 1970s returning in some places.

8. The end of the never ending story - Satyajit Das writes at Economonitor about the end of the mining boom in Australia and wonders if the lucky country might eventually share the fate of Nauru. It was the world's richest country in the 1960s and 1970s because of phosphate mining, but frittered and lost its fortune once the guano was gone.

The resource sector has high levels of foreign ownership; for example, foreign ownership of LNG projects is over 80%. This means that once in operation earnings from projects may flow overseas rather than remaining in Australia, limiting the benefits. The high capital cost equates to large tax write offs, depreciation and capital allowances, which means that the tax revenue benefit to Australia may be much less than expected for some time.

Mining also exploits non-renewable resources. Australia has economic demonstrated reserves of iron ore which at the 2009 production rate would last 71 years. The comparable figures for coal and LNG are 98 years and 61 years. However, this overstates the sustainability of Australia’s mineral wealth.

Low cost reserves are exploited first. As low cost reserves, such as the Pilbara iron ore reserves and Bowen Basin coal resources, are depleted, Australia’s resource competiveness will decrease. This will be compounded by the country’s high cost structures and its poor record in terms of cost escalation, which will encourage investors to look elsewhere.

This line is particularly telling.

Australia may have substantially wasted the proceeds of its mineral booms, with the proceeds channelled into consumption. The nations did not channel enough into strategic long term investments or develop a new industrial base. According to one study, the commodity boom increased government revenues between 2002 and 2008 by around A$180 billion of which A$36 billion was used to repay public debt, A$69 billion was placed into the Future Fund (to meet the cost of public sector superannuation liabilities) and $75 billion was transferred to households in the form of tax cuts and payments.

He points out unilateral banking regulation just rammed through parliaments in France and Germany reveal EU banking union plans to be flawed.

The most important signal sent by the unilateral legislation in France and Germany is the lack of political will to sort out the banking mess, which is at the heart of the eurozone crisis. Instead, governments are seeking refuge in symbolic gestures.

In the wake of the immediate crisis, the priority should have been the recapitalisation of the banks with public money, the closure and merger of weak banks, and to ensure that banks are not trying to adjust their balance sheets by running down loans to companies. This is what is happening in southern Europe now. My estimate is that the eurozone’s banking system is undercapitalised to the tune of €500bn to €1tn. The problem is not only Spanish banks, but also German and French ones, which have been more skilful at hiding their losses. If the recovery turns out to be as shallow as I expect, these losses will show up not too long from now.

10. Totally Jon Stewart on China hacking into US newspaper systems and Iran shooting a monkey into space.

12 Comments

#6, I was going to comment on it, the interesting thing is the effect of demographics....its a brilliant experimental output of an aging population on an economy.....our future if nothing melts down....yet ppl think we are going to see good growth and inflation return.....japan shows not.

regards

http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/business/aussie-builders-we-cant-give-i…

Australian housing developers are resorting to discounts, gift cards and help with mortgage payments to compete for dwindling buyers as home sales slow.

Stockland, Australia's biggest listed home builder, is giving rebates and gift cards of as much as $30,000 at projects in Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales states.

Little mention anywhere about NZ Herald's Sunday story about how the eSOE's have cooked the books over the past decade to double electricity rates above what they should be. Cheap energy is what drove modern economies. WE no longer have it and are suffering needlessly.

Who says that the mining " boom " was ending in Australia , Bernard ?

... the last time I looked , the price of iron ore was back up ... OK , the froth and bubble has left the market , but the industry as a whole is still in fine health ...

But for the ill thought out super-profits-mining-tax , which sent many companies scurrying for cover , and put dozens of new projects on hold , the mining industry would currently be positively robust ... ....

and the net benefit of the tax ? ...

even the Greens in the Federal Senate are asking of Julia Gillard how many profits it raised for the government ..... methinks zero $ ... but it did give Julia the top job !

7. Venezula did the same for eggs, result no eggs for sale....

regards

Mainzeal in Receivership - another Sth Canty Finance size disaster, I would expect direct govt intervention to protect subbies to be consistent

Fat chance....

regards

Yes - of course the government will bail them out - far more benefit bailing Mainzeal than bailing SCF and various others eh!

not surprised, I've been calling the slow train wreck of the NZ economy (in particular construction) for the last 2-3 years.

The bank economists say all will be swell, unemployment down below 6% in a year....yeah right

Me - I think my prediction of around 7 - 7.5% at year's end is looking too optimistic. Spoke to a mate in the weekend who works in a big engineering company and he reckons something is going to give soon - too many big companies, not enough work.

If it climbs above 8% nationally (9% + in Auckland) then housing prices in Auckland will become vulnerable

watch out

I worked in engineering for 20+ years, every time there was a downturn I either got made redundant, or the threat was there. Throw in that for a B.Eng the money was mediocre at best, and then to follow with threatened periods of un-employment and I moved into IT, never looked back...except to feel sorry for those still in it. You are right there is simply to little such work in NZ for the excessive numbers of engineers.

JK has said I think that he intends to target un-employment this year, he has to....but I agree I think he and we will be lucky if we can keep it where it is for the next 2 years. If he's serious he has to get exporters moving, to do that the exchange rate has to get down to 7%, that means the OCR has to be 1.5% and stay there for 2 years...

fat chance.

regards

Emergency action required - slash the OCR now!

#5 - typical Utopian drivel.

Companies are far quicker to react to changed markets, regulatory environments or structural constraints, than Gumnuts can be in devising or creating them. It has ever been so, since the first major company (Dutch East Indies: VOC) was allowed to emerge by Royal Charter.

And, most telling, this type of proposal has to be transnational, or it simply invites a race-to-safe-havens offered by opportunitic national Gumnuts. For a current working example of this reaction in - er - action, see Boris the Johnson's overtures to French firms leery of their own tax-and-spend Gumnut.

Anyone with more than a couple of functioning neuron, keen on seeing the UN (motto: let's hold committee meetings until they're all dead), trying to get this all up and running?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.