Here's my Top 10 items from around the Internet over the last week or so. As always, we welcome your additions in the comments below or via email to bernard.hickey@interest.co.nz.

See all previous Top 10s here.

My must read today is #2 from Ambrose on China's property market. Some of the charts are startling.

1, China and moral hazard - The eyes of the financial markets are on China's property market, its shadow banks and how Beijing deals with the stresses building inside China's financial system.

Earlier this year the Government engineered a bailout of the 'Credit equals gold #1' (the name makes me smile every time) shadow bank.

But earlier this month it allowed Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy to default on its corporate debt, which was, believe it or not, the first corporate debt default in China's modern corporate debt history.

Now there are reports a major property developer in Ningbo, Xingrun Properties, is on the verge of collapsing under the weight of US$570 million of debt.

It seems Premier Li Keiqiang, who overnight agreed to direct convertibility of the NZ$ with the Renminbi, was reported as saying that 'isolated cases of default will be unavoidable.'

This raises that hoary old chestnut of the modern era: when should Governments let financial instititutions fail to avoid the problem of moral hazard for term depositers and bank managers? The US Federal Reserve and Treasury engineered a bailout of Bear Stearns early in 2008 and then let Lehman fail in September, but quickly relinquished the high ground in the moral hazard debate when AIG threatened to destroy the world just a few days later.

Some think 'Credit equals Gold' was China's Bear Stearns moment. Now we wonder if it's about to have its Lehman and AIG moments.Here's Minxin Pei at the FT with a few thoughts on the issue of moral hazard:

Few are likely to share Mr Li’s optimistic view that only “isolated cases of default” will occur. Still, by speaking publicly of the possibility that investors will suffer losses on credit products, he indicated that Beijing may be ready to face the consequences of its decision to prop up growth with credit-fuelled investment. In the past five years credit has grown at an average of 20 per cent a year, more than double the average rate of economic growth over the same period. An astonishing $14tn of new credit has been extended since 2008. Much of this has been spent on building fixed assets such as infrastructure, real estate and factories.

As China’s macroeconomic environment deteriorates, a vicious cycle has taken hold. Slowing growth prolongs the country’s overcapacity problem, depresses prices of goods (such as coal and steel) that have attracted large speculative investments, and destroys the profitability of projects built on rosy assumptions of continuing high growth. The day of reckoning has now arrived. Beijing has two options, both of them unpalatable. It can either admit the obvious and start deleveraging, reducing the rate of credit issuance and allowing borrowers to default when they cannot meet their obligations. Or it can continue to prop up zombie borrowers with more credit.

Should it opt for the latter, a deceptive calm may last for a year or two. But when the inevitable crisis arrives it will be disastrous. According to estimates by Fitch Ratings, at the current rate of credit growth, China’s ratio of debt to gross domestic product will exceed 270 per cent by 2017. Interest payments alone will reach 20 per cent of GDP in that year.

I'm not necessarily suggesting some type of financial ructions inside China would cause New Zealand major grief, even though China is clearly now our largest trading partner. Australia has more to lose than us from a slump in investment in concrete and steel.

We may actually do well out of an internal switch inside China's economy towards consumption-led growth, given our exports are mostly about protein consumed by a fast-growing and increasingly-wealthy urban middle class. Those underlying drivers of urbanisation and rising incomes are unlikely to be hit too hard.

But we still need to watch. China is now the major driver of a good chunk of our economy.

2. Here comes the correction - Ambrose Evans Pritchard writes at The Telegraph about what a collapse of Xingrun Properties might mean for China. He cites some Nomura research.

“As far as we know, this is the largest property developer in recent years at risk of bankruptcy,” said Zhiwei Zhang, from Nomura.

“We believe that a sharp property market correction could lead to a systemic crisis in China, and is the biggest risk China faces in 2014. The risk is particularly high in third and fourth-tier cities, which accounted for 67pc of housing under construction in 2013,” he said.

Nomura said the number of ghost towns has spread beyond the well-known disaster stories of Ordos and Wenzhou to at least eight other sites. Three developers have abandoned half-built projects in the 2.5m-strong city of Yingkou, on the Liaodong peninsular. They have fled the area, a pattern replicated in Jizhou and Tongchuan.

Yu Xuejun, the Jiangsu banking regulator, said developers are running out of cash. This risks undermining land sales needed to fund local government entities. “Credit defaults will definitely happen. It’s just a matter of timing, scale and how big the impact is,” he said.

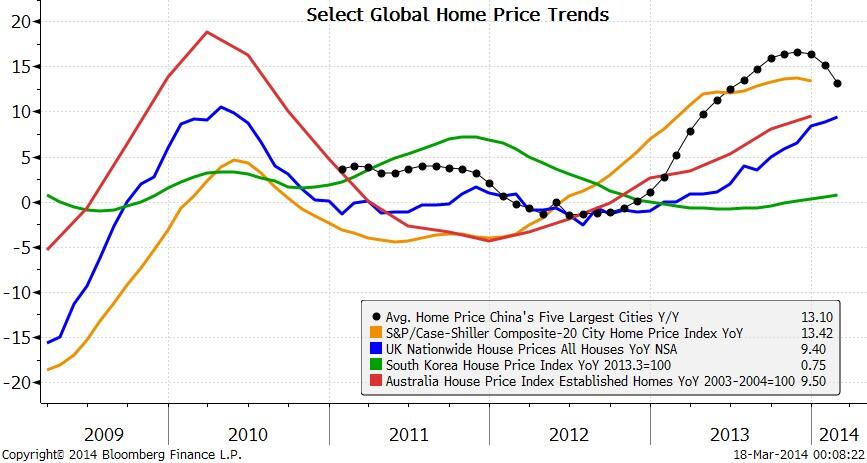

3. Don't be so sure about urbanisation - Ambrose also highlights that urbanisation in China is not as much of a sure thing as we in New Zealand think. The chart below showing a turning point in house prices inside China is also interesting. China is the black dotted line. Australia is the red line.

Optimists hope that the country’s urbanisation drive will stoke demand for years to come, but this too is in doubt. China’s workforce contracted by 3.45m in 2012 and another 2.27m in 2013 as the demographic crisis began to bite. The number of fresh rural migrants to the cities each year has already halved from 12.5m to 6.3m since 2010. Nomura said there could be net outflows by 2016.

4. China's American syndrome - Paul Krugman points to the issues inside China in this piece, suggesting a 'Minsky Moment' is near. He points to some chunky research here.

In the middle years of the last decade, China was able to sustain growth despite weak consumer spending thanks to massive and growing trade surpluses. But as the surplus eroded, it turned to sustaining extremely high and probably low-return investment via credit expansion — and now debt levels are looking scary.

We used to worry about America experiencing a China syndrome; but maybe we now need to worry about China experiencing an America syndrome.

5. An Anzac solution? - Former Reserve Bank of Australia Deputy Governor and now Lowy Institute fellow Stephen Grenville has suggested Australia joins with New Zealand to create a bigger more powerful nation and economy. He seems keen. I'm not so sure, but here's his case: (His equating of New Zealand and Tasmania and the use of the word mendicant is not encouraging)

We wouldn't merge in order to elbow other countries aside with sheer physical heft. We'd mainly do it because of its intrinsic logic. Countries and economies do best with a mixture of diversity (to avoid putting all our eggs in one basket) and homogeneity (so that we don't use up too much energy getting along with each other). Putting Australia and New Zealand together would improve the mix.

Looking first at our external positions, Australia has (sensibly) followed its comparative advantage into heavy dependence on resources and on a single customer: China. New Zealand's comparative advantage is in growing grass, so it dominates the global milk trade, again with China as main customer. This specialisation creates vulnerabilities which could be reduced by aggregating our export mix.

With essentially interchangeable legal systems, this would be one of the easiest amalgamations of all time. Australians shouldn't dwell on the fact that we offered New Zealanders the opportunity of inaugural membership of the Federation and for more than a century they haven't felt the need to take up our offer. The constitutional paperwork is still there, just waiting to be dusted off.

6. The IMF's new prescription - The IMF is particularly interested these days in reducing inequality and has a few suggestions here on how governments could do it.

Options for redistributive policies that help minimize efficiency costs, in terms of their effects on incentives to work and save, are the following:

In advanced economies: (i) using means-testing, with a gradual phasing out of benefits as incomes rise to avoid adverse effects on employment; (ii) raising retirement ages in pension systems, with adequate provisions for the poor whose life expectancy could be shorter; (iii) improving the access of lower-income groups to higher education and maintaining access to health services; (iv) implementing progressive personal income tax (PIT) rate structures; and (v) reducing regressive tax exemptions.

In developing economies: (i) consolidating social assistance programs and improving targeting; (ii) introducing and expanding conditional cash transfer programs as administrative capacity improves; (iii) expanding noncontributory means-tested social pensions; (iv) improving access of low-income families to education and health services; and (v) expanding coverage of the PIT.

Innovative approaches, such as the greater use of taxes on property and energy (such as carbon taxes) could also be considered in both advanced and developing economies.

7. Re-fighting yesterday's battle tomorrow - This WSJ blog by Justin Lahart wonders whether central bankers are too focused on inflation because they are old and their formative experiences were during the inflationary 1970s and early 1980s. Fair point.

Serious inflation has been absent from the American scene for years–but for the Federal Reserve, the threat remains omnipresent. Indeed, recently released transcripts show that even in the dark days of the 2008 financial crisis, many Fed officials were more worried about inflation than the economy collapsing around them.

Maybe they’re just born that way.

8. Why escaping the Malthusian trap is not enough - The Economist's Buttonwood writes more here about the Thomas Piketty book on economic growth, wealth and inequality that everyone is talking about because it suggests the reduction in inequality seen from the 1940s to 1980s is not a natural state. Maybe, Buttonwood suggests, we need to get used to widening equality and that politics may not redress the balance.

What stands out is the way that the last 400 years, and in particular the 20th century, breaks from the rest of history. Both population growth and economic growth have been much faster than before. We escaped from the Malthusian trap.

But we know, going forward, that population growth is likely to slow. Projections from the UN indicate that global growth will average 0.7% a year between 2012 and 2050, and then slow to 0.2% between 2050 and 2100. By the second half of the current century, the only area to show a population rise will be Africa. Asia's population will be falling, along with that of Europe where a decline is expected for the first half of the century as well.

So we know that, even if productivity pessimists like Robert Gordon are wrong, total economic growth will slow as well. To assume that productivity will grow faster than before is an act of the purest optimism.

In a previous post, I argued that the assumption that this situation was sustainable didn't allow for the existence of democracies or indeed for 1789-style mass revolts against entrenched wealth.

But, of course, one can reason in the other direction. Democracy came about, in part, because the rising middle classes and industrial working classes demanded political recognition for their increased economic power. But if economic power has gone back to the rich, we may be sliding back into plutocracy, where government is controlled by the rich; look at the expense of US political campaigns or Larry Bartels's work on the correlation between congressional votes and the views of their better-off constituents.

9. A failure of ideas - David Sainsbury of the Sainsbury fortune in Britain has written a thoughtful piece here at Project Syndicate about how the failure of the Maggie Thatcher free-market reforms of the 1980s and beyond has yet to spark any real alternatives. He has a few ideas.

In the new global economy, which is awash with cheap labor, Western economies will not be able to compete in a “race to the bottom,” with firms seeking ever-cheaper labor, land, and capital, and governments seeking to attract them by deregulating and shrinking social benefits.

The only way Western economies will be able to compete and improve their standard of living is by seeing themselves as being involved in a race to the top. That is, firms must improve their value added through innovation in existing industries, and by developing the capability to compete in new and more sophisticated industries, where value added is generally higher.

Companies will be able to do this only if governments abandon the belief that they have no role to play in the economy. In fact, the state has a key role to play in providing the conditions that enable dynamic companies to innovate and grow.

10. Totally Clarke and Dawe on Australia's immigration policy 'debate'. I laughed. If only we could get them to do their thing on New Zealand politics.

4 Comments

At the time of Federation New Zealand was closer, easier to get to and had more ties to NSW and Victoria than Western Australia did

"(i) using means-testing, with a gradual phasing out of benefits as incomes rise to avoid adverse effects on employment"

is it just me or are there a lot of BIG assumptions present in that suggestion? Sounds like a case of counting chickens to me.

#5: Stephen Grenville needs to read up on a bit of history. In spite of the "bigger is better" and "economies of scale" drivel that they still teach at universities, confederations and empires of various descriptions have been failing with clockwork-like regularity for the past few thousand years at least. Start with Greece, then the Roman Empire and now the EU....just to name some minor examples. These schemes only serve the in-power elites and lead to monopolies and other anti-competitive structures and corruption that never serve the greater good. However, like old-time communists and socialists, these guys keep spouting the same failed theories with religious-like fervour....

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.