Here's my Top 10 items from around the Internet over the last week or so. As always, we welcome your additions in the comments below or via email to bernard.hickey@interest.co.nz.

See all previous Top 10s here.

My must read today is #9 from Martin Wolf on the subject of Quantitative Easing, who 'creates' money and how banking really works. Have a great Easter.

1. A missing middle class? - One of the great achievements of the last 20 years or so has been the growth of incomes in emerging markets such as China and Latin America.

A growing middle class are demanding consumer goods and services, and luckily for us protein and tourism.

The growth of China's middle class is one of the major reasons New Zealand's economy has fared as well as it has in the last five years.

It has happened at the same time as intense pressure on the real incomes of the middle classes in developed economies, particularly in America.

But the FT's Shawn Donnan and John Burn-Murdoch reckon there's a good chance about one billion of the newly minted middle class could fall back into poverty because of slowing growth rates in the emerging markets.

New Zealand is relying on the continued unbroken growth of these middle classes for its future so it's well worth a read.

One of the things that concerns development economists is that, even before economies began to slow, the “churn” between those below and those immediately above the poverty line remained high. According to the World Bank, in countries such as Indonesia more than half of those below the poverty line were above it the year before.

The International Labor Organisation said it was already seeing the effect of slow growth in emerging economies, with the number of workers worldwide in extreme poverty declining only 2.7 per cent in 2013, one of the slowest rates seen over the past decade.

In an interview, Kaushik Basu, the World Bank’s chief economist, warned that many of those people who had emerged from poverty in recent years remained “very vulnerable” to slipping back. He also said the world economy faced risks, including the possibility that China’s growth could slow even more than it has already, something that would have big repercussions for the developing world.

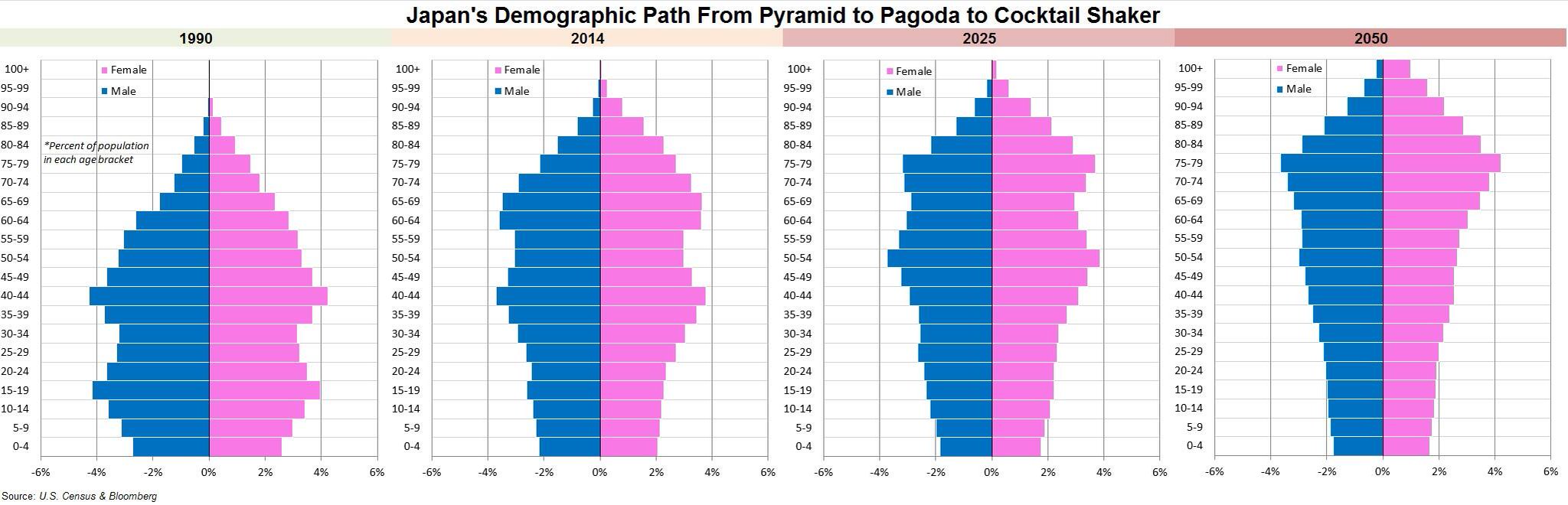

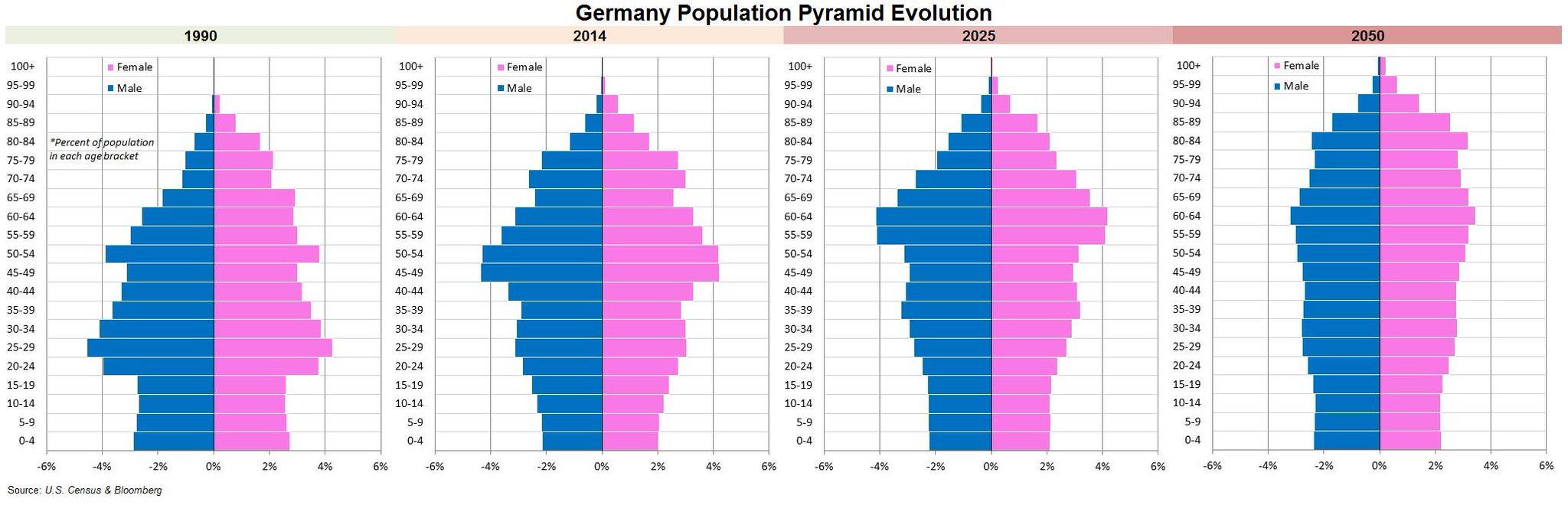

2. The pig in the python of ageing - Sometimes it's worth looking at the age structure charts of the major economies to get a sense of how economies, incomes, savings, jobs and politics are changing.

These charts are worth a look to see the scale of the issues, particularly in China and Germany. Japan is the baseline.

3. China's growth slows - Chinese GDP grew at an annual rate of 7.4% in the March quarter, a tad slower than its previous target, but slightly above the median economist forecast. Credit growth also fell 19% from a year ago, Bloomberg reports.

An extended slowdown would put pressure on Premier Li Keqiang to add stimulus or ease up on efforts to curb financial risks and property-price gains after this month outlining spending and tax relief to support growth. A weaker Chinese economy would limit a pickup in global expansion forecast by the International Monetary Fund and restrain demand for commodities including copper and iron ore.

4. So where's the stimulus? - Everyone is waiting and waiting for a significant Chinese stimulus to get Chinese growth going again. There've been a few murmurings, but nothing much yet.

Here's Business Spectator with a look at why the stimulus may not come and why it's a good thing.

5. Here comes the carry trade again - BNZ Chief Economist Tony Alexander points in his weekly update to the growing pressure on the New Zealand dollar from yield hungry investors looking for higher interest rates somewhere else.

Investors will reignite the carry trade whereby they borrow in a low interest rate country and invest in a high rate country to gain extra yield while taking what they think can be a managed exchange rate risk. That means ongoing support for the NZ dollar, especially with our economic growth story going to be so good for the next three years that investors will consider the exchange rate risk inherent in the carry trade to be very low.

In addition, the global search for property is leading investors to NZ with Chinese families in particular looking for stores of value for their rising wealth away from the control of the CCP. The level of foreign buying of residential and commercial property in NZ is going to continue to rise and that will not only push property prices higher and deepen the affordability debate, it will again give additional support to the NZ dollar.

6. Too big to fail is too big to ignore - Martin Wolf at the FT hits the nail on the head in this piece about the problem of banks being too big to fail and why leverage needs to be restricted ever lower.

The Reserve Bank and our Government continue to persist with the figleaf of Open Bank Resolution, which allows the Government and the banks to continue to kid themselves, voters and depositors that moral hazard exists and banks would not be rescued.

It's just baloney. While our Government is solvent, it will of course bail out the banks. We have a track record overseas to rely on and the repo facility set up by the Reserve Bank in late 2008 and early 2009 proved it here in New Zealand.

Here's Wolf on the problem of too big to fail overseas, which is arguably bigger than here, but not as much as most would have you believe.

No solvent government will allow its entire banking industry to collapse. Leveraged institutions whose liabilities are more liquid than their assets are inescapably vulnerable to panics. In a panic, it will be hard to distinguish illiquidity from insolvency. These three points shape my views: the state stands behind banking even though it might not stand behind individual institutions.

One of the obstacles to making the bearing of losses by creditors credible is “too big to fail” – the challenge posed by banks that are individually systemic. A question about post-crisis regulation is whether this risk is gone. The answer is no. Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England and chairman of the Financial Stability Board, himself agrees that “firms and markets are beginning to adjust to authorities’ determination to end too-big-to-fail. However, the problem is not yet solved.”

7. The Great Moderation v 2.0 - Gavyn Davies looks in this FT blog at whether the world is now entering a second era of 'Great Moderaton' where growth is moderate and lasts for a long time with low inflation.

Brilliant. Until....

I've bolded the important bit. All very topical given #5 above.

Here's Davies:

Prolonged periods of moderate expansion, with very low interest rates, usually prove to be good for risk assets, including credit, carry currencies and equities.

Of course, none of this precludes the possibility that the current expansion and bull market will end the same way as occurred in 2008, with a “Minsky moment” in a financial system that has reached too far into risk assets. There are some worrying signs of this in the recent froth in the IPO market for internet and biotech stocks, which now seems set to correct quite sharply. But overall global equity market valuations do not seem to be in bubble territory yet.

Central banks will have to watch all this increasingly carefully, since GM 2.0 could certainly result in an excessive reach for yield and other forms of dangerous risk-taking. It already seems clear that the markets have not learned their lesson in this regard, and both the Fed and the Bank of England look likely to deploy regulatory and capital controls to discourage excessive risk-taking fairly soon. A major question for investors will be whether the bull market can survive such measures, which were of course conspicuously missing in the cycles of GM 1.0.

8. A melting pot of charts and people - This is an excellent infographic from Statistics NZ showing the different population structures of the different ethnic groups as measured in last year's census. The pigs in the pythons are at vastly different stages, which is a good thing overall.

9. How banks and money really work - Here's Martin Wolf again riffing on the Bank of England paper on how the money system really works that has everyone talking about. It is an essential read.

Banks are not just financial intermediaries. The act of saving does not increase deposits in banks. If your employer pays you, the deposit merely shifts from its account to yours. This does not affect the quantity of money; additional money is instead a byproduct of lending. What makes banks special is that their liabilities are money – a universally acceptable IOU. In the UK, 97 per cent of broad money consists of bank deposits mostly created by such bank lending. Banks really do “print” money. But when customers repay, it is torn up.

Second, the “money multiplier” linking lending to bank reserves is a myth. In the past when bank notes could be freely exchanged for gold, that relationship might have been close. Strict reserve ratios could yet re-establish it. But that is not how banking operates today. In a fiat (or government-made) monetary system, the central bank creates reserves at will. It will then supply the banks with the reserves they need (at a price) to settle payments obligations.

Quantitative easing – the purchase of assets by the central bank – will expand the broad money supply. It does so by replacing, say, government bonds held by the public with bank deposits and in the process expands the reserves of the banks at the central bank. This will increase broad money, other things being equal. But since there is no money multiplier, the impact on the money supply can be – and indeed has recently been – modest. The main impact of QE is on the relative prices of assets. In particular, the policy raises the prices of financial assets and lowers their yield. The justification for this is that at the zero lower bound normal monetary policy is no longer effective. So the central bank tries to lower yields on a wider range of assets.

This is not just academic. Understanding the monetary system is essential. One reason is that it would eliminate unjustified fears of hyperinflation. That might occur if the central bank created too much money. But in recent years the growth of money held by the public has been too slow not too fast. In the absence of a money multiplier, there is no reason for this to change.

A still stronger reason is that subcontracting the job of creating money to private profit-seeking businesses is not the only possible monetary system. It may not be even the best one. Indeed, there is a case for letting the state create money directly. I plan to address such possibilities in a future column.

10. Totally Jon Stewart on the Ukrainian crisis - The Friday Funny. Or not very, depending on who you are.

23 Comments

http://www.interest.co.nz/category/people/bill-english

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11238867

So which is it, Bill? If it really was the Greens - who've never been in power, despite the PM and some other Minister who's name I forget claiming otherwise - you'd just have to conjure up some 'pro-growth' legislation, from your position of legislative power. Easy peasy.

You can't, because it isn't the problem, Absolute physical limits to growth within any given finite parameter is your problem, Mr English. You ran smack into the last doubling-time of them all, on this watch. T'was predicted, you just somehow weren't listening.

What was the one about the left hand and the right hand - seems to me the problem is that the right hand doesn't know what the right hand is doing, this time. Thanks for the laugh, Minister.

I have figured out why Asian males want to come here - there is a greater % of women than in their country!

#9 is a complete list of why Banks need to be Nantionalised, and the experts put into real jobs

The "incredibly high" prices of New Zealand dairy farms have prompted Aquila Capital to switch its investment drive to Australia, where the dairy sector offers "the best risk-adjusted returns in global agriculture".

http://www.agrimoney.com/feature/incredibly-high-nz-land-prices-divert-…

AEP at his best

The United States has constructed a financial neutron bomb. For the past 12 years an elite cell at the US Treasury has been sharpening the tools of economic warfare, designing ways to bring almost any country to its knees without firing a shot.

The strategy relies on hegemonic control over the global banking system, buttressed by a network of allies and the reluctant acquiescence of neutral states. Let us call this the Manhattan Project of the early 21st century.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/ambroseevans_pritchard/10771…

Andrewj. I'm actually rather shocked that such a controversial article made it into the pages of the Telegraph, the bastion of conservative political discourse. Perhaps there is a growing anti-American sentiment among Britain's the ranks of Britain's conservative thinkers. Perhaps they're resentful of the United States almost complete displacement of Britain's preeminence in world affairs.

The notion of the U.S. Treasury department acquiring financial tools and tactics capable of bringing any country they desire to their knees dates to well beyond twenty years ago.

The banking sysem that has come to take such a pervasive role in our lives is a product of an elaborate, premeditated, carefully orchestrated plan, which began in the mid 1970s due to the frustration of many within Big Business interests with the historic bargain between Business and Labour which found expression in the New Deal and Johnson's Great Society. They became concerned about the rise of historically marginalized groups such as the student movement and African American civil rights, which they framed in terms of the "Crisis of governability" (See Samuel Huntington's, Crisis of Democracy). Read the American journalist, Mill Moyers Memorial Speech to John Gardner, former principal architech of Johnson's Great Society and President of Carnegie Corporation of New York. and the growing power and influence of resource rich emerging economic nations which came together under the umbrella of the Group of 77, who were leveraging the abundance of natural resources crucial to the West''s industrial economies to gain influence and concessions from the world powers.

"See for yourself. Read the literature. Start with A Time for Truth, the call to arms by Richard Nixon’s treasury secretary, William Simon, the Wall Street wheeler-dealer. He argued that “funds generated by business” would have to “rush by multimillions” into right-wing causes in order to uproot the institutions and the “heretical” morality of the New Deal. He called for an “alliance” between right-wing ideologues and “men of action in the capitalist world” to mount a “veritable crusade” against everything brought forth by the long struggle for a progressive America. It would mean, as Business Week noted at the time, “that some people will obviously have to do with less...It will be a bitter pill for many Americans to swallow the idea of doing with less so that big business can have more.” But so be it. "

http://carnegie.org/publications/carnegie-reporter/single/view/article/item/282/

Or going back to 1968, where Treasury Secretary George Ball, advocated the creation of a suprapolitical structure to relieve then existing constraints on the action of multinational corporations, due to what he thought was an imbalance in the scope of national governments and multinational business.

"He went on to note the problem of governance of the international firm, given the asymmetry between its scope and that of national authorities, and called for the evolution of some sort of supranational political structure. Recognizing that was not likely, he suggested ‘denationalizing’ MNEs as a second best solution, governing world corporations through a treaty-based international companies law administered by an international institution. ""

http://www-management.wharton.upenn.edu/kobrin/Research/Oxford%20rev2%20print.pdf

It culminated in a research project carried out by the American thinktank, called the Council on Foreign Relations, which was aimed at determining what political and economic reforms were needed to be carried out that would alleviate the necessity of accomoditing rising demands for change that threatened the current social order. One of the publications was a book entitled, Alternatives to Monetary Order, the purpose of which was to conceptualize the reframing of world monetary arrangements that would best ensure the continuation of the pattern of economic relationships, favourable to the interests of the United States. Its conclusion was, œThe obvious danger in such a regime resides in its potential instability. Some limited loosening is by no means unequivocally undesirable. It can be seen as a rational response to the earlier tendency, which was most manifest in the 1960s, for economic integration to run far ahead of both actual and desired political integration, thereby forcing countries into suboptimal policy choices. A degree of controlled disintegration in the world economy is a legitimate objective for the 1980s and may be the most realistic one for a moderate international economic order. A central normative problem for the international economic order in the years ahead is how to ensure that the dis-integration indeed occurs in a controlled way and does not rather spiral into damaging restrictionism.â€

Alternative to Monetary Disorder (Fred Hirsch and Michael Doyle, CFR)

http://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/inecon/v8y1978i3p457-459.html

I myself was horrifed when I read an excerpt of the above and to confirm it authencity I actually ordered a second hand from Amazon. I assure you it is, shocking though it may be.

And the mechanism which they used to achieve their purpose was the high interest rate policy of Paul Volcker, Federal Reserve Bank goveror, which he freely admitted below.

www.newyorkfed.org/research/quarterly_review/.../v3n4article1.pdf

Thanks Anarkist, the connectedness we desire creates our very vulnerability. Perhaps its time we thought about systems functioning independent of external forces, I'm sure Russia is.

And TPP rolls on.

I'm still at a loss to why Libya got taken out, baffles me. I don't trust the EU either.

Have you read this book, I haven't.

C.W.Mills - The Power Elite

http://www.amazon.com/The-Power-Elite-Wright-Mills/dp/0195133544/ref=sr…

One of the commentors on the telegraph

Financial war? But the US engaged in financial war against the UK and Europe when they deliberately, knowingly and intentionally offloaded toxic debt onto our banks with the connivance of US banks, knowing that the US property crash was coming. They drove us into recession in order to save their own skins from the result of their own stupidity and greed - and we are still kissing the US's a*se. I sincerely hope that Russia brings the US crashing down. I believe they are up to it because the Russians can put up with hardship; the US can't.

hey Andrewj,

Funny how you mention Libya in the topic of States, like Russia who may wish to seek independant economic functioning in the age of connectivity and interdependance.

"....What do these seven countries have in common? In the context of banking, one that sticks out is that none of them is listed among the 56 member banks of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). That evidently puts them outside the long regulatory arm of the central bankers' central bank in Switzerland.

The most renegade of the lot could be Libya and Iraq, the two that have actually been attacked. Kenneth Schortgen Jr, writing on Examiner.com, noted that "[s]ix months before the US moved into Iraq to take down Saddam Hussein, the oil nation had made the move to accept euros instead of dollars for oil, and this became a threat to the global dominance of the dollar as the reserve currency, and its dominion as the petrodollar."

According to a Russian article titled "Bombing of Libya - Punishment for Ghaddafi for His Attempt to Refuse US Dollar", Gaddafi made a similarly bold move: he initiated a movement to refuse the dollar and the euro, and called on Arab and African nations to use a new currency instead, the gold dinar. Gaddafi suggested establishing a united African continent, with its 200 million people using this single currency."

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/MD14Ak02.html

We live in age of constant conflict. We will just have to get used to it.

"There will be no peace. At any given moment for the rest of our lifetimes, there will be multiple conflicts in mutating forms around the globe. Violent conflict will dominate the headlines, but cultural and economic struggles will be steadier and ultimately more decisive. The de facto role of the US armed forces will be to keep the world safe for our economy and open to our cultural assault. To those ends, we will do a fair amount of killing."

The U.S. government and its foreign collaborators don't seem to be satisfied with destabalising the Ukraine and the toppling of its government which has precitated a confrontation between the Great Powers not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis, but are intent on the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Venezuela when the election didn't go their way.

.http://truth-out.org/news/item/22043-violent-protests-in-venezuela-fit-…

I suspect Chávez was a bit of a dude. We got mislead by western media, a tragedy

http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2013/03/06/chavezs-dead-what-does-big-…

You have prbably seen John Pilger on Chavez, just in case you haven't

From what I have read Chavez is one of the best leaders of modern times. I want to watch that but don't really have the time just now.

Pretty convenient for the powers that be that Chavez died of cancer at such a relatively young age.

Many in the Left accuse the United States of being responsible for his death. Just is well his death wasn't in vain, he had time to ensure his succession, which has what's pissed off the United States and the wealthy in Venezuela, who thought to capitalize on his death with putting their own people in power and dismantling his reform. Nice to see a viable alternative to neoliberal capitalism however imperfect it is.

Graham on The Telegraph may be representative of the views of many of his compatriots, but he also may wish to be careful what he wishes for. A financially destroyed US is a benefit to nobody, as the US is still far and away the world's pre-eminent economy.

Reading the comments under many of the Guardian's articles, I am increasingly observing a strong anti-US sentiment that is based on various events -- the invasion of Iraq, the NSA spying scandal, and a generalised dislike among Guardian readers of what they consider the US to represent -- the home of neoconservatism. Even as a GenX, I still feel a bit sad that the common bond formed between the US and the UK through WW2 is now fading.

I'd agree that it's a feeling of the decline of empire that's might be underneath it, just the same as some in the west also feel the same feeling towards the development of China.

Jetliner, you want to read some of the anti government comments on USA bloggs and newspapers, makes one start to fear the future.

There are a lot of disadvantaged and unhappy citizens in the good old U.S of A just waiting for a chance to strike out.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/04/17/us-usa-ranchers-nevada-militi…

I know what you mean, Andrewj. Whatever negativity Guardian commentators have, they don't usually support armed opposition of their own government. As far as US newspapers go, I read the NY Times every day, whose readership is not exactly representative of the rest of the country, I know.

Some of the antigovernmentalism's a hangover from the South's loss of the Civil War, I suspect, as well as a general suspicion of East Coast bureaucrats and politicians. Motives such as the Texas secession and the Southern "rebel identity" are some of the prime motivators of domestic US militarism, I'd say. These most probably link into the socioeconomic disadvantages that you mention, especially now that unskilled/low-skill employment is getting harder to find in some areas.

Don't need to worry about that, we already have the likes of Profile here on interest.co doing that, and the management here wilfully accepting of it.

Bernard I am not completely convinced by Martin Wolf at #9. QE is essentially the reserve bank buying money that has already been created (loaned into circulation) by private banks, which is why it isn't inflationary. But that doesn't mean hyperinflation won't come, sooner or later a move will be made to increase borrowing. If that isn't done by the public (private banks) then it will be done by central government borrowing. Perhaps a war might be the impetus.

However I will ponder on this some more.

Scarfie,

Hyperinflation doesn't happen through the normal financial conduits, it generally happens after a catastrophic economic event and the desperate measures by government to resolve the crisis and forestall capital flight. particularly through money printing. Hyperinflation is an unlikely event in the case of the United States, being the world's reserve currency, but if it does happen, it will be a mere symptom not a major problem itself. We'll have worse things to worry about. Like the total collapse of the world's economy and financial markets.

I tend to agree that history does show this, but that doesn't necessarily predict the outcome of the current situation. GFC, and the associated peak of energy, is a catastrophic economic event but measured on a different time frame to past events. Lol. The way I read this article is that QE isn't actually money printing, but it is simply propping up the private banks ability to print. As I say, buying money that has already been printed and I would take that further and say this is with the hope it frees the way for business as usual. But I don't see that business as usual is happening and in fact the money aggregates are going the wrong way. Certainly velocity is well down, but the (M.V)+i=P.Q predicts that. So my comment from when I first conceived that equation as been that money printing will have to happen to counter the falling velocity, and thus keep GDP (the right side of the equation) positive. That process will be exponentially expanding and will lead to hyperinflation.

The question remains how? You may have also caught my comment in the past about growth requiring an expanding consumption of resources and that a failure of the private sector to do this will eventually bring attempts by central government to spend the way out of trouble. War could be one possibility and could be a way of trying to avoid financial collapse.

I am not sure with the interconnectness of finance that you can isolate one country from the equation, but yes possibly the effects. But the USA is certainly a lot better off than many in terms of energy, so you could be right. As the world empire they are still the beneficiary of the wealth transfer but that will surely kill off the fringes at some stage. Mexico on the front door though and about to run out of energy to export.

We could already be in deflationary collapse as an alternative to all this, as destruction of capital (read debt) is the other scenario. What I mean there is that all the financial assets are a debt somewhere else in the system and that those debts won't be repaid. The crunch only comes when there is an admission they money is gone. Certainly the current situation is not right and there is a divergence between financial and real assets increasing exponentially in size.

Thinking out aloud about what I have said. I would look to the GDP print for timing on preventative, or reactive, actions with the money supply.

#8 Can we conclude that in the near future, it would be our Maori, Pasifika and Asian populations that would be support the aging European population? Make sense to increase immigration.

How does that make sense in any way? To provide a solution you have to first identify the cause of the problem.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.