Here's my Top 10 links from around the Internet at midday in association with NZ Mint.

As always, we welcome your additions in the comments below or via email to bernard.hickey@interest.co.nz.

See all previous Top 10s here.

My must read today is #1-10. I've done something a bit different. I have linked to a speech and that speech only. That's one speech and 10 links about it. It's that good. I recommend everyone read the speech in full. It's 46 pages long. Those in the government who use slogans such as 'funny money' or 'wacky economics' or just utter the words 'Zimbabwe' or 'Weimar Republic' in response to talk about 'money printing' should definitely read it.

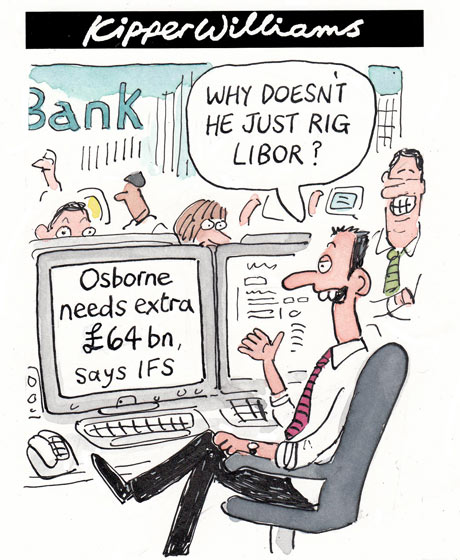

1. Helicopter money - The head of Britain's Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner, has thrown a huge cat amongst the monetary policy and banking policy pigeons with this February 6 speech titled: 'Debt, money and Mephistopheles: How do we get out of this mess?'. HT to Anatole Kaletsky and David (in yesterday's Top 10) for pointing me to this.

This is my must read for today.

Turner's speeches often are.

He has to be the most established and connected member of the economic establishment in the Western World who is seriously questioning the orthodoxy of monetary and banking policy. His argument is detailed, considered and backed up with all sorts of academic research and data. It's about as far from 'funny money' as you could get.

Just a reminder. This guy is in charge of regulating banks in Britain. He is no fringe party nutter or blogger.... ;)

Here's the speech and here's the speech slides.

It is five and a half years since the financial crisis began in summer 2007 and four and a half years since its dramatic intensification in autumn 2008. It was clear from autumn 2008 that the economic impact would be large. But only slowly have we realised just how large: all official forecasts in spring 2009 suggested a far faster economic recovery than was actually achieved in the four major developed economies – the US, Japan, the Eurozone and the UK. UK GDP is now around 12% below where it would have been if we had continued the pre-2007 trend growth rate: and latest forecasts suggest that the UK will not return to 2007 levels of GDP per capita until 2016 or 2017.

In terms of the growth of prosperity this is truly a lost decade. This huge harm reflects the scale of pre-crisis financial folly – above all the growth of excessive leverage - and the severe difficulties created by post-crisis deleveraging. And failure to foresee either the crisis or the length of the subsequent recession reflected an intellectual failure within mainstream economics – an inadequate focus on the links between financial stability and macroeconomic stability, and on the crucial role which leverage levels and cycles play in macroeconomic developments. We are still crawling only very slowly out of a very bad mess.

And still only slowly gaining better understanding of the factors which got us there and which constrain our recovery. We must think fundamentally about what went wrong and be adequately radical in the redesign of financial regulation and of macro-prudential policy to ensure that it doesn’t happen again. But we must also think creatively about the combination of macroeconomic (monetary and fiscal) and macro-prudential policies needed to navigate against the deflationary headwinds created by post-crisis deleveraging.

2. And then he thinks the unthinkable and says the unsayable.

At the extreme end of this spectrum of possible tools lies the overt money finance (OMF) of fiscal deficits – “helicopter money”, permanent monetisation of government debt. And I will argue in this lecture that this extreme option should not be excluded from consideration for three reasons:

(i) Because analysis of the full range of options (including overt money finance) can help clarify basic theory and identify the potential disadvantages and risks of other less extreme and currently deployed policy tools;

(ii) Because there can be extreme circumstances in which it is an appropriate policy; and

iii) and because if we do not debate in advance how we might deploy OMF in extreme circumstances, while maintaining the tight disciplines of rules and independent authorities that are required to guard against inflationary risks, we will increase the danger that we eventually use this option in an undisciplined and dangerously inflationary fashion.

3. He calls it overt monetary finance (OMF).

Even to mention the possibility of overt monetary finance is however close to breaking a taboo. When some comments of mine last autumn were interpreted as suggesting that OMF should be considered, some press articles argued that this would inevitably lead to hyper inflation. And in the Eurozone, the need utterly to eschew monetary finance of public debt is the absolute core of inherited Bundesbank philosophy. To print money to finance deficits indeed has the status of a moral sin – a work of the devil – as much as a technical error.

In a speech last September, Jens Weidmann, President of the Bundesbank, cited the story of Part 2 of Goethe’s Faust, in which Mephistopheles, agent of the devil, tempts the Emperor to distribute paper money, increasing spending power, writing off state debts, and fuelling an upswing which however “degenerates into inflation, destroying the monetary system”(Weidmann 2012).

4. Even Milton Friedman was a fan, says Turner

Before you decide from that that we should always exclude the use of money financed deficits, consider the following paradox from the history of economic thought. Milton Friedman is rightly seen as a central figure in the development of free market economics and in the definition of policies required to guard against the dangers of inflation. But Friedman argued in an article in 1948 not only that government deficits should sometimes be financed with fiat money but that they should always be financed in that fashion with, he argued, no useful role for debt finance.

Under his proposal, “government expenditures would be financed entirely by tax revenues or the creation of money, that is, the use of non-interest bearing securities” (EXHIBIT 1) (Friedman, 1948). And he believed that such a system of money financed deficits could provide a surer foundation for a low inflation regime than the complex procedures of debt finance and central bank open market operations which had by that time developed.

When economists of the calibre of Simons, Fisher, Friedman, Keynes and Bernanke have all explicitly argued for a potential role for overt money financed deficits, and done so while believing that the effective control of inflation is central to a well run market economy – we would be unwise to dismiss this policy option out of hand.

5. Friedman suggested 100% money financing of government deficits.

His (Friedman's) conclusion was that the government should allow automatic fiscal stabilisers to operate so as “to use automatic adjustments to the current income stream to offset at least in part, changes in other segments of aggregate demand”, and that it should finance any resulting government deficits entirely with pure fiat money, conversely withdrawing such money from circulation when fiscal surpluses were required to constrain over buoyant demand. Thus he argued that, “the chief function of the monetary authority [would be] the creation of money to meet government deficits and the retirement of money when the government has a surplus”. Friedman argued that such an arrangement – i.e. public deficits 100% financed by money whenever they arose – would be a better basis for stability than arrangements that combined the issuance of interest bearing debt by governments to fund fiscal deficits and open market operations by central banks to influence the price of money.

His conclusion was that the government should allow automatic fiscal stabilisers to operate so as “to use automatic adjustments to the current income stream to offset at least in part, changes in other segments of aggregate demand”, and that it should finance any resulting government deficits entirely with pure fiat money, conversely withdrawing such money from circulation when fiscal surpluses were required to constrain over buoyant demand. Thus he argued that, “the chief function of the monetary authority [would be] the creation of money to meet government deficits and the retirement of money when the government has a surplus”. Friedman argued that such an arrangement – i.e. public deficits 100% financed by money whenever they arose – would be a better basis for stability than arrangements that combined the issuance of interest bearing debt by governments to fund fiscal deficits and open market operations by central banks to influence the price of money.

6. How money is really created - Turner talks about Friedman and post-Depression economist Henry Simons here too. Those who saw Seven Sharp's banking piece last week and wrote it off as crackpot should read this in particular.

Friedman thus saw in 1948 an essential link between the optimal approach to macroeconomic policy (fiscal and monetary) and issues of financial structure and financial stability. In doing so he was drawing on the work of economists such as Henry Simons and Irving Fisher who, writing in the mid-1930s, had reflected on the causes of the 1929 financial crash and subsequent Great Depression, and concluded that the central problem lay in the excessive growth of private credit in the run up to 1929 and its collapse thereafter.

This excessive growth of credit, they noted, was made possible by the ability of fractional reserve banks simultaneously to create private credit and private money. And their conclusion was that fractional reserve banking was inherently unstable. As Simons put it “in the very nature of the system, banks will flood the economy with money substitutes during booms and precipitate futile efforts at general liquidation afterwards”. He therefore argued that “private institutions have been allowed too much freedom in determining the character of our financial structure and in directing changes in the quantity of money and money substitutes”.

As a result Simons reached a conclusion which gives us a second paradox from the history of economic thought. That the rigorously freemarket Henry Simons, one of the father figures of the Chicago School, believed that financial markets in general and fractional reserve banks in particular were such special cases that fractional reserve banking should not only be tightly regulated but effectively abolished.

7. Turner goes on to say it's time to wind back the leverage of banks - Remember, he's the regulator of banks in Britain...

By the way, here's David Chaston's excellent table of the leverage of New Zealand's banks. They're not as bad as those in America and Europe. But still too high, in my view.

Even if we reject the radical policy prescriptions of Simons, Fisher and early Friedman, their reflections on the causes of the Great Depression should prompt us to consider whether our own analysis of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent great recession has been sufficiently fundamental and our policy redesign sufficiently radical. Three implications in particular may follow.

First, that while there is a good case in principle for the existence of fractional reserve banks, social optimality does not require the fraction (whether expressed in capital or reserve ratio terms) to be anything like as high as we allowed in the pre-crisis period, and still allow today6. As David Miles and Martin Hellwig amongst others have shown, there are strong theoretical and empirical arguments for believing that if we were able to set capital ratios for a greenfield economy (abstracting from the problems of transition), the optimal ratios would likely be significantly higher even than those which we are establishing through the Basel III standard.

Second, that issues of optimal macroeconomic policy and of optimal financial structure and regulation, are closely and necessarily linked. A fact obvious to Simons, Fisher and Friedman, but largely ignored by the pre-crisis economic orthodoxy. As Mervyn King put it in a recent lecture, the dominant new Keynesian model of monetary economics “lacks an account of financial intermediation, so that money, credit and banking play no meaningful role”. Or, as Olivier Blanchard has put it, “we assumed we could ignore the details of the financial system”. That was a fatal mistake.

And third, that in our design of both future financial regulation and of macroeconomic policy, it is vital that we understand the fundamental importance of leverage to financial stability risks, and of deleveraging to post- crisis macro-dynamics.

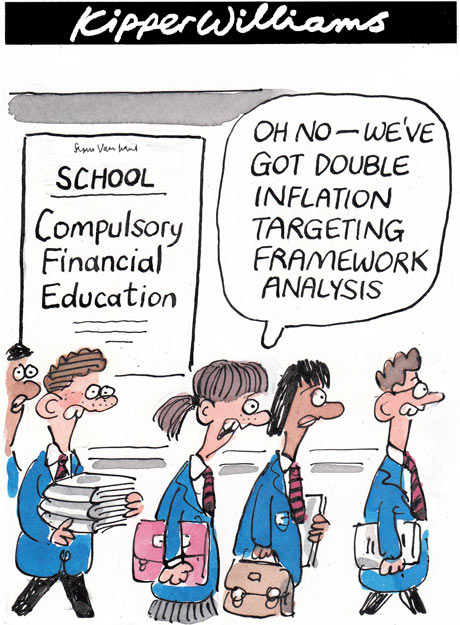

8. Turner then goes on to say the unsayable again by suggesting pure inflation targeting be reconsidered. New Zealand is the purest (and first) of the inflation targeters.

The increasingly dominant assumption of the last 30 years has been that central banks should have independent mandates to pursue inflation rate targets. The specifics vary by country, but orthodoxy and practice has tended to set price stability as the objective and to define price stability as low but positive inflation, for instance around 2%. Central banks typically pursue that objective looking forward over medium-term timeframes e.g. over two to three years. That orthodoxy is now extensively challenged, and a plethora of alternative possible rules have either been already applied or are now proposed.

Blanchard et al questioned in 2010 whether a period of somewhat higher inflation might be required to cope with the challenges of high debt levels and attempted deleveraging (Blanchard et al., 2010). The Federal Reserve has adopted a policy of state contingent future commitment, with a clearly stated intent to keep interest rates close to the zero bound and to continue quantitative easing until and unless employment falls below 6.5% or inflation goes above 2.5%.

Mark Carney has suggested that a range of possible options, including a focus on nominal GDP, should at least be considered. And Michael Woodford, author of a canonical statement of pre-crisis monetary theory (Woodford, 2003) has proposed that central banks should conduct policy so as to deliver a return to the trend level of nominal GDP, which would have resulted from the continuation of pre-crisis NGDP growth.

So why is our own central bank and our new central bank governor stonewalling this debate in the face of a massive reassessment overseas? Are we somehow immune or not involved in the global economy? Are our heads in the sand?

That's when Overt Monetary Finance (OMT) is needed.

He points out, for example, that the existing form of QE may turn out to be more like pure deficit financing because it may not be reversed. Ie. The bonds could be cancelled. So there's not much difference.

All QE operations therefore carry within them the contingent possibility that they will turn out post facto to have been (in part or whole) permanent monetisation: and that this may be an appropriate policy. The gross debts of the government of Japan, after netting out holdings by the Japanese government amount to 200% of GDP: of this 200%, around a sixth (i.e. 31% of GDP) is held by the Bank of Japan (EXHIBIT 32). Whether this debt exists in any meaningful economic sense, or whether an element of Japan’s past fiscal deficits has been de facto money financed, is a moot point.

10. And OMF isn't necessarily hyper-inflationary, says Turner.

There is, moreover, no inherent technical reason (as against political economy reason) to believe that OMF will be more inflationary than any other policy stimulus, or that it will produce hyperinflation It is no more inflationary than other policy levers provided the “independence” hypothesis holds. If spare capacity exists and if price and wage formation process are flexible, the impetus to nominal demand induced by OMF will have a real output as well as a price effect, and in the same proportion as if nominal demand were stimulated by other policy levers.

Conversely if these conditions do not apply, the additional nominal stimulus will produce solely a price effect whether it is stimulated by OMF or by any other policy lever. And the impacts on nominal demand and thus potentially on inflation will depend on the scale of the operation: a “helicopter drop” of £1bn would have a trivial effect on nominal GDP: a drop of £100bn a very significant effect and as a result create greater danger of inflation. And if the stimulative effect of OMF subsequently proved greater than anticipated or desired, it could be offset by future policy tightening, whether in the extreme form of Friedman’s “money withdrawing fiscal surpluses” or through the tightening of bank capital or reserve requirements.

The idea that OMF is inherently any more inflationary than the other policy levers by which we might attempt to stimulate demand is therefore without any technical foundation.

55 Comments

Am I allowed a "told you so". Great to see someone of authority articulating (admittedly much better than I ever did) what I've been trying to say here for about 18 months.

Thanks Bernard.

Strangely enough I discussed this on Seven Sharp last week:

http://tvnz.co.nz/seven-sharp/paying-interest-loan-never-existed-video-…

And in NZ Investor magazine last year (note the focus on capital limits):

http://sustento.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/NZ-Investor-Piece-Mon…

And with Kim Hill back in 2011:

http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/saturday/audio/2502425/raf…

And with the Minister of Finance back after the February 2011 Earthquake (also previous approaches in 2008-2009)

http://sustento.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2007/05/A-New-Financial-Deal-…

And previously back in the UK in 2001:

"At the meeting of the Monetary Reform forum in the House of Lords on 12th December 2001 Raf Manji suggested that we should propose an amendment to the next budget bill: that the proposed Public Spending Borrowing Requirement (PSBR) of £3billion should be created into existence by the government."

It's crystal clear that the Central Banks have been printing money for a long time (Japan for 20 years), just as it's clear that the private banking system has always created the credit that makes up most of the money supply. We just need to realise that we can spend that new money directly into the economy and not rely completely on banks. When that realisation comes, suddenly the world looks a very different place.

Raf, what sort of response, if any, did you get from Bill English?

This monetisation of debt really shows a flaw in the understanding of debt. Debt is a claim on future production and resources. If they futher can't deliver, which is likely, then the debt doesn't majically go away by printing, but is simply defaulted on.

New money isn't debt but a representation of current production and resources. The main issue is whether there are enough resources available.

Really its energy, which there is not, enough of, ergo default.

regards

I would go further and state that paper money is merely an evolved proxy for energy. In the final analysis it is energy which props up the whole financial system, whether it be the energy expended by one individual toiling in a rice paddy for a day or the energy burned in a tank of fuel as a jet crosses the Pacific. Energy is the linchpin resource. By extension then debt is merely a future call on energy yet to be produced/exploited/discovered - the implications of this for the debt based system on a finite planet on which our primary sources of energy are rapidly depleting should be very obvious to the economic elite (but are seemingly not). You can talk about monetizing debt or whatever you wish to call it as a solution to our financial problems until the cows come home - but it will have less than zero effect on miraculously creating new sources of energy out of thin air. To be honest I find very little thats new or of interest in this speech (other than the fact that clearly at some point in desperation this approach will be tried and this is part of the softening up process). Much more central to understanding how the system works was this piece from a month ago which was surprisingly completely ignored on interest.co.nz:

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/files/2013/01/Perfect-Storm-LR.pdf

Yes. I posted your link on my facebook wall for a while :-)

Forgive my typos as it should read "if the future can't deliver".

Just a follow up - I did not realise that the promulgation of this speech had Anatole Kaletsky's finger prints all over it. Why Kaletsky is still given a platform is way beyond me - rewarding failure is the least of it. Anyone familiar with his columns for the UK's Sunday Times in the period from say 2000 till the GFC will have realised that he was completely blind-sided by the events of that period. He was unrelentingly in the Blair/Brown borrow to spend /there is no housing bubble camp which has effectively bankrupted the UK.

...good link andyh. You might want to try reading the Cannibals and Kings: The origin of cultures, by Marvin Harris. He published this over 20 years ago and in the last chapter looking forward he predicts the same conclusion as the excellent report you posted. Mind-bending stuff!

Sounds like an interesting read, will try and get a copy thanks.

I wont have a chance to read this end to end til I get home, but a quick read shows its pretty good IMHO.

Thanks

regards

So right andyh.

This is a well written piece and I can't believe it isn't #1 in a Top 10, instead we get more drivel from an economist/banker.

Meh

I'm pretty sure I've linked to that Tullet Prebon piece on energy and growth before. It's very good.

cheers

Bernard

It is very good Bernard. Andyh first linked it in comments to the Top 10 on 24 Jan and I'd be surprised at how many have actually read it. I agree with Andyh that it needs wider circulation hence his suggestion that it be a seperate article.

Cheers

Meh

pt1...helecopter money.

If one was to "print money"... then this way would be by far the most equitable and fair way to do so.

This could also tie in with Gareth Morgans'.. "big Kahuna"... idea of a universal "wage".

Even thou ,philosphically, I don't buy into "printing money".... I can see that if used prudently , and if it was done in this, equitable, way.... I can see that it would/could be a very useful policy tool.

I think we are all sick to death of this money printing... where the main beneficieries are the Banks and banking system , themselves....

Cheers Roelof

Ironic - on the same day Ralph Norris takes on a Board position with NZ Treasury :-).

This is just another guy not wanting to pay his debts run up in the bubble. If he can't pay them, let him default, and the asset price deflate. If we keep trying to scam the game by financial tricks like printing money, there is a massive moral hazard. No reason not to run up big bubbles, by borrowing wildly on over-inflated asset prices - just print money later and everything will be fine. I think deflation would be far preferable. This would clean out of all those who acted irresponsibly causing the bubble in the first place - rather than rewarding them by re-inflating asset prices with money printing.

So, call to action - perhaps a Reader Poll, BH?

Should we buy shares in:

- Fuji Xerox, or

- Rayonier-Matariki Forests, or

- Smith & Wesson

Inquiring minds.....

Smith & Wesson.

Expand it to,

Just about any ammo manufacturer and reloader supplier you care to mention.

regards

Thanks for the tip Pilgrim.

That is hilarious guys, but then sad when you read AJ below.

In California there is no ammo. The gun club cancelled its shoot due to no 9mm ammo available. There are no guns on the shelves, no .233 ammo or any other pistol, out of 308, 306 and most of the rest, out of relaoding supplies no primers nothing. No pistols left on the shelf empty walls.

I had to go in with a friend because they are rationing ammo to 40 rounds ahead, I gave him my share. I wish I could post a photo of the empty shelves at all the gun shops around here.

Aj

I assume it'll be in response to this?

Got your get outta Dodge plan at the ready, Aj?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dodge_City_War

But seriously, I was a kid living in a nice, middle class white suburb of Chicago during the infamous riots during the 1968 Democratic Convention there .. and the talk by the gun toting neighbours was seriously scary... you know the 'bring it on..' type attitude. Given local police forces are state and locally funded (and we know how well that's going in more than a number of states) - well, I wouldn't wanna be there or be trying to get outta there these days.

Don't a lot of Americans keep weapons to defend themselves not against each other but to protect themselves from the Federal Government. Most Federal Agencies including environmental ones and the IRS have heavily armed SWAT teams now and feel the need like their armed forces and intelligence services to generate "enemies" real or imagined to justify budgets.

The FBI and ATF assault and murder of the Branch Davidians at Waco in the 1990's was a prime example. The documentary Waco - The Rules of Engagement (1997) is the most compelling case of abuse of federal power I have seen. Both agencies wanted payback and to make an example of the Davidians after bungling the initial raid. So they incinerated 70 odd men, women and children.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uCfzLFIT5QM

Also the US perhaps more than any other nation celebrates and glorifies its military. A "might is right" mentality isn't conducive to tolerance or negotiation.

The second Ammendment.

regards

Did you know that most bullet proof vests won't stop high calibre centrefire rounds (.308) inside 100m? I think the FBI forgot that at Waco.

Kate, its about jobs around here, no jobs. The unemployment is chronic.

I just spend a day up the mountain and its very much white middle class but very few people, the lift workers were complianing about how quiet it is and how bad the economy is.

A lot of anti government sentiment all over the western world these days not just the USA, but the unemploymnet is making this place hurt worse than most. Lots of beggars in every town.

Gas is back over $4 a gallon again which will slow the economy. Need high oil prices so the banks can recycle all the US$ you need to buy the stuff.

I suspect there are people around here with enough ammo to start a war, the remnants of Cromwell's army

On the otherside the sharemarket is almost at record highs so 'sunny days' again.

The other crazy thing is the conterfeit 20$ bills about the place, all the shops have a magic pen they use to check every single bloody note.

Where are you exactly, still in the dust bowl of Northern Califonia ..where are there no jobs, basically 100% unemployment and where they checking every USD bill...are you visiting Afghanistan by chance? :-)

I can imagine - according to this (April 2012) Calif. unemployment rate was 11% with only 39% of those unemployed getting any form of unemployment benefit.

http://images.businessweek.com/ss/08/12/1224_states_unemployment/index.htm

An armed and desperate population - recipe for disaster.

and the way the US records un-employment the real rate is far higher....youth un-employed is also the worry....young with nothing to lose and access to guns....not good.

regards

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cCPX9JnngM&list=UUWJHDMgKWWvOsdyRF3HPVE…

800% spike in gun sales.....

regards

plenty of ammo in LA, also tasers going cheap currently...

speckles, I spent last week at Bend Or, what a great part of the world. Mt Bachelor was fantastic and it felt so much better than it does down here.

The money problem with 20 $ bills is associated with the drug industry. Around here is a perfect place to grow hooch and the Mexican gangs are up here in summer. The police even had a shoot out last summer with a gang. The unemployment problem is bad North of Sacramento. Its bad all the way up i5. The towns on the way to Bend were sad, a bit like rural NZ.

Honestly the gun shops arond here are empty. Sportsmans wharehouse is a huge sports shop, notice all ammo is sold out.

http://www.sportsmanswarehouse.com/sportsmans/Handgun-Ammunition/catego…

http://www.sportsmanswarehouse.com/sportsmans/.223-Remington/category/c…

Yeah, maybe the central banks should just create a policy of PYO.

Print your own dollars.

Cheers Bernard...good read, wiil it become whisper to a scream...? not without a digestive aid.

Bernard forgets there is a part a and a part b.

".... His (Friedman's) conclusion was that the government should allow automatic fiscal stabilisers to operate so as “to use automatic adjustments to the current income stream to offset at least in part, changes in other segments of aggregate demand”, and that it should (A) finance any resulting government deficits entirely with pure fiat money, conversely (B) withdrawing such money from circulation when fiscal surpluses were required to constrain over buoyant demand.

How come the part B never eventuates and it hardly ever is even discussed.

Think of coins and notes as public money created by the reserve Bank, there to facilitate real economic activity, a lubricant if you like; and credit as private money, mostly digitally "created" by private banking corporations, mostly overseas owned, harvesting fees and interest and with no limits other than the populations ability to service that interest.

The first makes up less than 5% of the money supply, the second 95%. What's wrong with a bit of rebalancing? Why is private money/credit okay to create and loan to government projects like the Christchurch rebuild but its not okay for the RB to spend it into existence with no or little interest attached?

As Martin Wolf of the Financial Times notes:

"The essence of the contemporary monetary system is creation of money, out of nothing, by private banks’ often foolish lending. Why is such privatisation of a public function right and proper, but action by the central bank, to meet pressing public need, a road to catastrophe?"

Will someone, I wonder, ask Mr Key, English or Wheeler whether they have read the paper; whether they agree with it; and if not, why not? Where is the logical fault in it? Why should we not save ourselves billions in interest and principal; as well as not affect the exchange rate in the way we have been doing for decades, accepting that most of the rest of the world only changed after the GFC. The Nats have had 4-5 years of observing the ROTW acting differently, and so far have done nothing, and shown no signs of doing anything. In fact they are sarcastically hostile to even thinking about it, with facetious comments about Zimbabwe etc.

Approximate cost say $10 billion per annum; both fiscally, and separately, in the current account. A very expensive government indeed. Everything else they do is trivial in comparison.

Mr Hickey,

You have said much in the past that I have admired and respected, but I'm afraid that in recent times you've lost the plot. I try to be mild mannered, but my message to Adair Turner and all the others who feel that they have the right to use printing to confiscate my life savings is this:

#%*! you and the horse you rode in on.

nothing like waxing eloquent whilst ruffling a few feathers, but.....

Your 'life savings' are based on a misjudgement based on a chimera steeped in a religion. Those 'savings' expect to be able to purchase bits of the planet, in a thing called the future. A lot of other folk, also with no direct relativity to said planet, have concurrenly been storing up digital '1's and '0's.

Good luck in the auction....

The government is currently giving away your life savings to the Germans, Swiss, Japanese, Chinese, Aussies et al at a NZ wide rate of approximately $1 billion per month. Adair Turner points out that that process is unnecessary, with no more inflation effect than borrowing their money, or selling them assets, as we insist on doing at present.

Have you noticed the currency wars going on at present? Little else is being talked about on places like CNBC. New Zealand is just collateral damage. In fact we are walking out in front of the bullets saying "Hit me, hit me".

Seriously what choices do we have that dont court greater risk and impact? I'd lower the OCR 1%, true, but beyond that? uh no Really look at say Greece, when the investors run its in a few weeks and its over in at most 4 months. We just dont have the depth of defence of the EU or USA. If confidence drops in us then all that is left is to print and pay out in what will be wotrhless NZD...ie i dont think we'll see a "nice" correction but a large and nasty one.

Then listen to the screams compared to the whining we have now, we'll need ear defenders...

regards

ANZ chief economist Cameron Bagrie is already panicking and pleading for that never to be found fix it all "productivity" to redress the so-called imbalance - I have too much money deposited with this outfit - maybe I need to get the hell out and move the funds to one of the nations that Stephen L quotes while the NZ$ remains bid.

ANZ chief economist Cameron Bagrie said all four quadrants - business, the unions, central government and local government - need to get together to define a strategy to lift competitiveness and productivity.

"The bottom line is the New Zealand dollar is going to remain elevated for another couple of years. That's what people need to get their heads around.

"People are talking about intervening, printing money and cutting interest rates - but that is not going to do a thing. We need to identify a realistic solution we can achieve rather than taking pot shots at the Reserve Bank."

The "brutal reality" was the New Zealand economy had a mismatch of about 10 per cent between local fundamentals and where the currency resided.

"New Zealand needs to be targeting how we get that 10 per cent lift in productivity and competitiveness," Bagrie said.

To realign the New Zealand currency with local fundamentals, a ruthless obsession was needed across the nation, with all four quadrants prepared to give and take. Read article

Stephen,

You are absolutely right to be cynical about this frequent demand for us all to be "more competitive and productive".

Bagrie, who otherwise is normally reasonable, has notably left out the solutions. The government is doing some micro things like training and apprenticeships (although all governments do these things); but if your currency has gone up 33%, it is not realistic to either fire a third of your teachers and nurses and police and everyone else; nor to pay them all a third less. (That is the Greek solution in the end) A few less MPs, while perhaps desirable, wouldn't make much difference. Trading industries have had to find such savings to stand still, and if they haven't, they die.

And a further catch is that the system will always keep the carrot of a fairly priced currency (defined as say a balanced current account) a couple of feet in front of our nose. Get more productive, sell more and buy less from foreigners, and what do you know, the currency appreciates even further.

Getting the currency right is first prize; having it stable is second; not paying foreigners unnecessarily for debt is a bonus from 1 or 2.

Where we are now is several lengths back; a waste of otherwise great resources, and willing people.

I agree with Cameron Bagrie.

There should be short, medium and long term goals.

Short-term changes should see the immediate ceasing of all income taxation on those who pruduce exportable products. Include every worker involved.

This would drive the population into becoming efficient and having to produce something that is able to be sold off-shore.

If your not exporting or involved in the manufacturing of something that can be exported then your going to have to pay income tax and at a higher rate than now.

Rewarding people who take the risk and who are productive is sensible.

Disincentives to whose who are unproductive is also sensible.

The easy quick wins, based on Adair Turner's points, are to print at least that part of new government debt that would otherwise be borrowed from foreigners (and that ultimately right now is sourced from their money printing, so don't feel too bad about it).

Am not sure what proportion of government debt is foreign, but say three quarters in terms of ultimate source (including the Aussie Banks sourcing foreign funds for the government); then there would be approximately $9 billion per annum in saving on principal; and an extra 200 million in interest. By definitoin this would not increase our money supply one cent, so from that point of view would not be inflationary.

If this process happens to correct, or even stabilise, the NZD, then even better in terms of the effects on our trading industries. If it does not, then no loss at all to consumers, and zero effect on inflation.

"Seriously what choices do we have that dont court greater risk and impact?"

I think my point still stands....

I'd prefer the OCR drop myself rather than printing...its easy to recall the drop, not soo with some hundreds of millions printed. In fact Im pretty sure dropping the OCR is the first stage of "printing" and sicne we are at 2.5% and not 0.25% we shouldnt print, yet.

regards

Then Im afraid you are mis-guided, mis-informed or deluded.

After all the printing for 4 years just where is inflation? ie more moeny in ppls pockets? for most ppl except the parasitic; bankers and top 1%, nowhere. Thats the problem of the zero bound trap.

Consider the more likely scenario that they are printing to avoid, deflation and a severe recesion/depression...In times like that banks close.....wave bye bye to your money over a weekend.

Where do you think your interest comes from? well its either gained from a slice of a company's profits or its of say CCs which is parasitic...during a depression/recession both are hard to service.

Just where did you earn your money from? well ultimately over your working life, taking one time resources such as energy out of the earth and converting or wasting it. So far you have managed to use up half of it in about 70 years, the half that is left wont last 30 years....

and the interest you so think you deserve has to come out of what energy is left....

We have screwed ourselves, suck it up mate....

regards

Great article. Thanks at last some alternatives are appearing in the mainstream. Inevitable anyway as the world approaches the limits to growth but a planned approach to changing from an economy dependent on growth would be far more desirable than just continuing along with our eyes shut.

triple post!

fat chance, the re-alloction of what resources we have left need to re-directed away from iphones, new obsolete cars and mcMansions and into projects to reduce energy needs and build alternatives.

To start with no pollie will admit or say we need to start this on the scale of the run up to WW2 because they'd be laughed out of office. Throw in the vested interests who wont want change and think they can keep getting a bigger slice of a shrinking cake. And last but not least the voter who cant contemplate the 30 year 95% mortgage or other large and long term debt they have taken on will cost them all the have...and be either worthless (New Range Rover etc) or worth a lot less (huge house) to boot.

So the choice is, eyes wide shut....

regards

FYI Here's Matt Nolan's response to this Top 10

http://www.tvhe.co.nz/2013/02/13/overhyping-nothing-the-nz-context-for-…

cheers Matt

Evident from his discourse title, Turner makes a point of taking issue with Buba chef Jens Weidmann's very skeptical stance towards QE but disingenuously misrepresents Weidmann's arguments by quoting in selective fashion. Turner quotes Weidmann from his notorious Faust speech where he stated that printing money degenerates into inflation, destroying the monetary system and counters with the argument not if it is done correctly and in limited amounts. However Weidmann has also stated that printing money is a "sweet poison" to which governments too readily become addicted, to which Turner counters with not if controlled by rules and central bank independence (....as if). And to Weidmann's assertion that money printing destroys the incentive for economies in need of structural reform to undertake such reforms... well Turner doesn't really go there.

Case in point USA where Turner believes the current policy mix is reasonably successful and may post facto amount to OMF, but admitting so openly may simply make the politics more difficult. Really? Pretending that a lack of aggregate demand is the problem and this can be solved by QE, whereas structural issues (excessive debt, lack of competitiveness, unaffordable entitlements) remain unaddressed? Without politically suicidal structural reform the US will remain addicted to the "sweet poison" QE4EVA. Weidmann is right, Turner is wrong. Monetary system destruction is inevitable, the only question is when.

RT: You said the amount of the fiscal gap in the United States is, in your estimation, $222 trillion. This is an astonishing number, which is like three times the world GDP. This is more than what the world makes.

LK: Twenty times higher than the official debt in the hands of the public, which is $11 trillion. So if you add all the spending obligations into the distant future, and you compare them with all the taxes, and you include in the spending all the interest payments, and principal payments on the debt, and the official debt, you have $222 trillion of present value. Now, this is 12 per cent of GDP on an ongoing basis, and we need to get 12 per cent more in GDP either in tax increases or spending cuts in order to have the fiscal gap in zero.

We’re doing far too little, too late. It’s like operating on a person with cancer, and you say, “Well, there’s a big tumor here, we’re just going to take a little bit out today, and we’ll come back in five years, and we’ll take out some more.” But maybe in five years the patient is dead because the tumor got bigger. So this is why we are in worse shape than Greece – in Greece, it’s about 10 per cent of GDP they need on an ongoing basis, in Italy it’s about 5 per cent, in Germany it’s about 5 per cent. So when you look at it from this perspective, it’s a whole different story than if you look just at the official debt because these governments are making choices what to call official obligations, and what to call unofficial.

http://rt.com/usa/news/debt-crisis-us-kotlikoff-535/

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.