But there is more to the story. The divisive nature of the region’s illiberal governments precludes consensus-building, and has so weakened academic freedom and independent institutions that creative policy responses to economic challenges are being stifled. As a result, the only feedback mechanism in the region is demonstrations and civil disobedience. The vast protests now confronting Orbán’s regime may be just a taste of things to come.

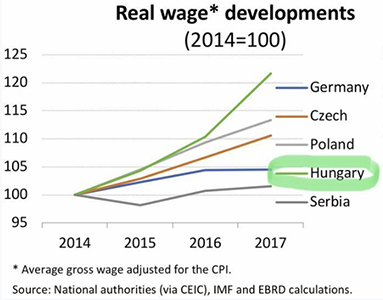

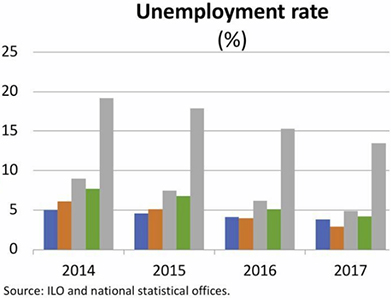

The conditions now facing the region would be difficult to manage for even the most nimble and open of governments, let alone the ideologically blinkered illiberal regimes of Hungary and Poland. Central Europe’s labor markets are tight and labor shortages abound. Unemployment has dropped while real wages have risen markedly (though their levels are still below the average for advanced European Union countries).

This state of affairs reflects strong growth in the region and a shrinking labor force. Central Europe’s economies have expanded at a rate of more than 3% annually in recent years, thanks to still-high EU transfers and domestic monetary policy stimulus in, or under the shadow of, the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing. According to a recent report by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, labor shortages, particularly of skilled workers, have become widespread in the region, as population aging and emigration shrink the workforce. Emerging Europe is “getting old before getting rich,” the EBRD notes. Automation also requires freshly skilled labor, which is missing from the marketplace. All of these factors are pushing wages up.

In Hungary, the unemployment rate dropped below 4% in the fall of 2018, while real wages have been growing at 6-7% annually for the past three years, despite stalling productivity growth (which itself appears related to the emigration of high-skill workers). Employers now complain about labor shortages, and multinational firms have reportedly been considering moving business back to the West or to cheaper EU candidate countries in southeastern Europe.

That is not an idle threat. Competition from re-shoring of production to Western Europe and from Southern Europe in the manufacturing sector threatens traditional jobs in Central Europe. Automation and rapid technology change in vehicle production make it easier to shift facilities to higher-wage advanced European economies, which would simplify firms’ logistics. Southern European EU candidate countries are in the process of adapting their laws to EU legislation, creating an EU-compatible business environment for FDI – and their wage levels and growth are considerably lower than in Central Europe.

It is against this background that Hungary’s government introduced its amendments to the overtime law. The law permits employers to demand up to 400 hours of overtime annually (equivalent to 50 additional working days), payable over a period of three years. If the employee leaves his or her job earlier than the contract stipulates, the remuneration may not be paid at all. With Orbán’s Fidesz party controlling a two-thirds parliamentary majority, the law was rushed through in less than a month.

Demonstrations exploded, forcing the government to publicly interpret some elements of the amended law more flexibly. The lack of consultation and the strong popular reaction are reminiscent of the government’s attempt in 2014 to impose an “Internet tax,” which was withdrawn in the face of popular protest.

Intervention and the use of top-down discretionary powers are the order of the day for right-wing governments. We have seen the use of utility price reductions and non-market-based asset transactions in Central European countries in recent years. In the United States, President Donald Trump pressures individual companies not to lay off workers or relocate business abroad.

And, as Tim Wu of Columbia University argues in his new book The Curse of Bigness, big business and autocrats tend to collude. In exchange for certain favors, corporates receive favorable treatment (such as monopoly powers and curtailment of workers’ rights). In Hungary, multinationals are considered the main beneficiaries of the “slave law.” But they are not alone: even the government now argues that the main beneficiaries will be small and medium-size enterprises, which comprise the new, politically connected private sector.

Central Europe is at an economic turning point. The old export-led convergence model based on access to the EU market and funding, supporting physical investment, productivity catch-up, and low labor costs, has served the region well, but it is exhausted. Central Europe needs a new innovation-based growth model based not on the price of labor, but rather on high-quality labor, which requires investment in education and lifelong training, as well as improved social policies. Budget spending must be prioritized accordingly and academic freedom, creativity, and dialogue – all increasingly in short supply – must be encouraged.

But the region’s illiberal democracies will have a hard time managing this shift, because they deter free thinking and innovation, and they loath expertise-driven institutions. In Hungary, for example, the government’s parliamentary majority obviates the need to consult with the opposition, or to work with the countries’ best minds and talents.

The good news here is that when the need to tackle economic change becomes unavoidable, the natural shortcomings of illiberal democracies will eventually lead to their erosion. The demonstrations and civil disobedience currently playing out in Hungary could be merely a taste of things to come.

Piroska Nagy-Mohacsi is Program Director and Senior Fellow at the Institute of Global Affairs, London School of Economics. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2019, published here with permission.

6 Comments

I know little about current affairs in Poland and Hungry and am a little skeptical of what I have read. However I would not trust anything written by this author - clearly she is unable to present both sides of an argument. Take ""the ideologically blinkered illiberal regimes of Hungary and Poland"" as a starting point. What is wrong with ideology - or does it have to be a left-wing ideology? Who defines what is and is not 'liberal'? So long as they remain democracies let their voters decide what they want; obviously they voted for a change at the last election.

meanwhile the idea that left wing labour governments are immune from influence by rich businessmen is a joke. What about Harold Wilson's resignation knighthoods to Lord Kagan and Eric Miller? What about Armand Hammer dealing with Lenin? What about Yikun Zhang receiving a New Zealand Order of Merit last September with praise from various Labour politicians. Oligarch's have always tried to influence governments. It is only aristocrats who have a cultural mechanism to resist them.

We're at an interesting time in human history. Knowledge has driven capitalism for 250 years but it is currently struggling to win over those who do not share in its world view. The reality is that people will learn & then earn, or not. If you will not learn, you will not earn - very much.

The problem with the rich is that they like to show it off, which just pisses every else off. If they paid their fair share of taxes & were more humble with their lot, then we probably wouldn't mind so much, but the press incessantly follow them around and show & tell everything they do & we all swallow it up like feeding ducks at the park. We need rich people. They create wealth by creating products or services that we all like & buy & use. This is how wealth is created. I like wealth. It gives me choices. A life with many choices is what I consider to be a good life.

Those people in wealthy countries that don't learn anything & don't earn anything only have themselves to blame.

In fact, you could argue that if you don't learn & don't earn & live your life on the dole, then your the winner, because all those people working & paying their taxes are underwriting their lazy lifestyle, so they're the winners, not those who work.

To me, the poor choose to be poor when they choose not to learn. They should be bloody grateful that we underwrite their failings. But they're not.

It's tough being middle class these days.

"" the poor choose to be poor when they choose not to learn "" that is just rubbish. Wealth is a mix of luck and knowing when to take the opportunity. I heard of a Auckland bus driver who sold his house and moved to Dunedin 15 years ago and now has reason to move back to Auckland. Somehow his family missed out on the half million mine made by staying put. Nothing to do with learning, just bad luck.

You are right about the rich and showing off. Some Asian immigrants like a house with an impressive frontage; I'm happy to have a house down a ROW that is hidden from the road; my wife comes from a Melanesian culture where it is considered 'bad luck' to have a house better than your neighbours. So you can find coffee millionaires who travel by helicopter but live in a small hut.

LJM,

You betray your ignorance and total lack of humanity. Dickens described people like you in language I cannot match. You clearly believe in the discredited trickle down theory whereby you cut taxes for the rich and everyone else gets the crumbs that fall from their table-and as you so graphically put it,should be bloody grateful for it.

Who uses tax havens? I doubt if even you believe that its the poor people. Remember the Panama Papers?

Next time I donate to my local Foodbank I will be sure to tell them not to give anything to the undeserving poor.

I pity people like you.

Good article, interesting as we don't hear much from that neck of the woods.

However Right wingers tend to have small Govt interventions and Left wing( think China, Russia, North Korea Venezuela etc) have a definite leaning to top down "discretionary powers", to say the least.

"intervention and the use of top-down discretionary powers are the order of the day for right-wing governments"

(Our Labour led Govt must be pretty right wing then by her logic??: think Twyford's compulsory land acquisition, Kiwibuild, School hubs etc)

I see she did time at the LSE, so must be quite a bit between the ears anyway.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.