By David Skilling*

The headline from China’s ‘two sessions’ meetings over the past week was the (optimistic) ‘around 5%’ GDP growth target for 2024. But also of significance was the ongoing commitment to ‘high quality growth’, with a focus on industrial sectors and advanced technologies.

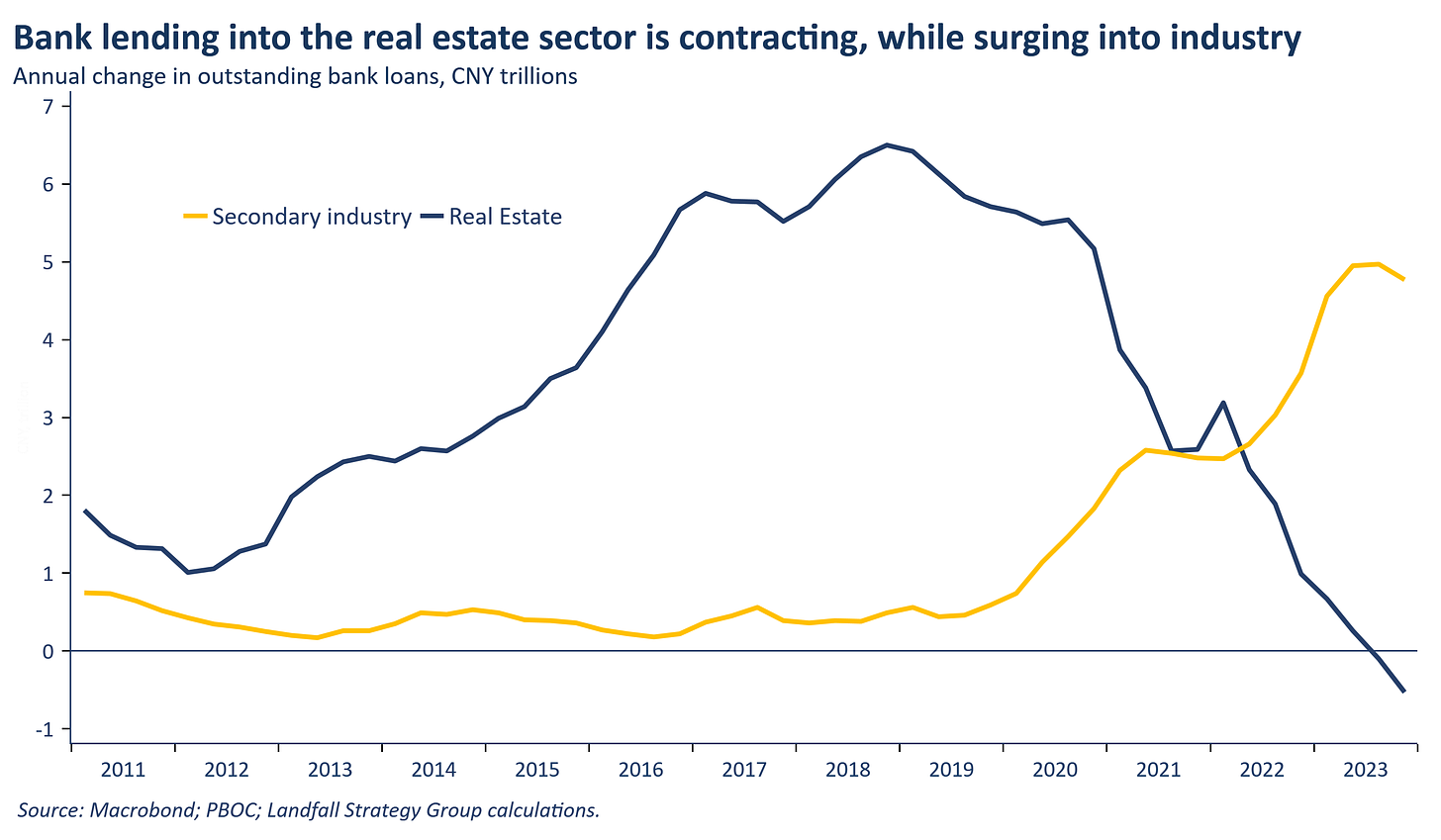

There is an aversion to consumption-driven growth, with little increase in fiscal stimulus or reforms to the social insurance system. Export-oriented industrial growth will be an important contributor to achieving the ~5% GDP growth target. Indeed, there is an ongoing rotation away from the property sector as a driver of growth: bank lending into real estate is declining while increasing into industry

Relatively weak domestic demand in China (national savings are >40% of GDP), and the sectors in which China is developing positions of strength, mean that export markets are the vent for surplus. China is now the world’s largest car exporter (overtaking Japan last year) and is a major player in renewables (solar, turbines, batteries). China remains the world’s manufacturing superpower, accounting for ~30% of global manufacturing value added.

And China is determined to maintain this leading position, with significant support flowing into priority sectors (such as EVs, AI, renewables). Substantial over-capacity has been built in a range of Chinese industrial sectors. This will generate a meaningful deflationary impulse into the global economy: China’s export price index was down ~8.4% in the year to December.

Surplus economy

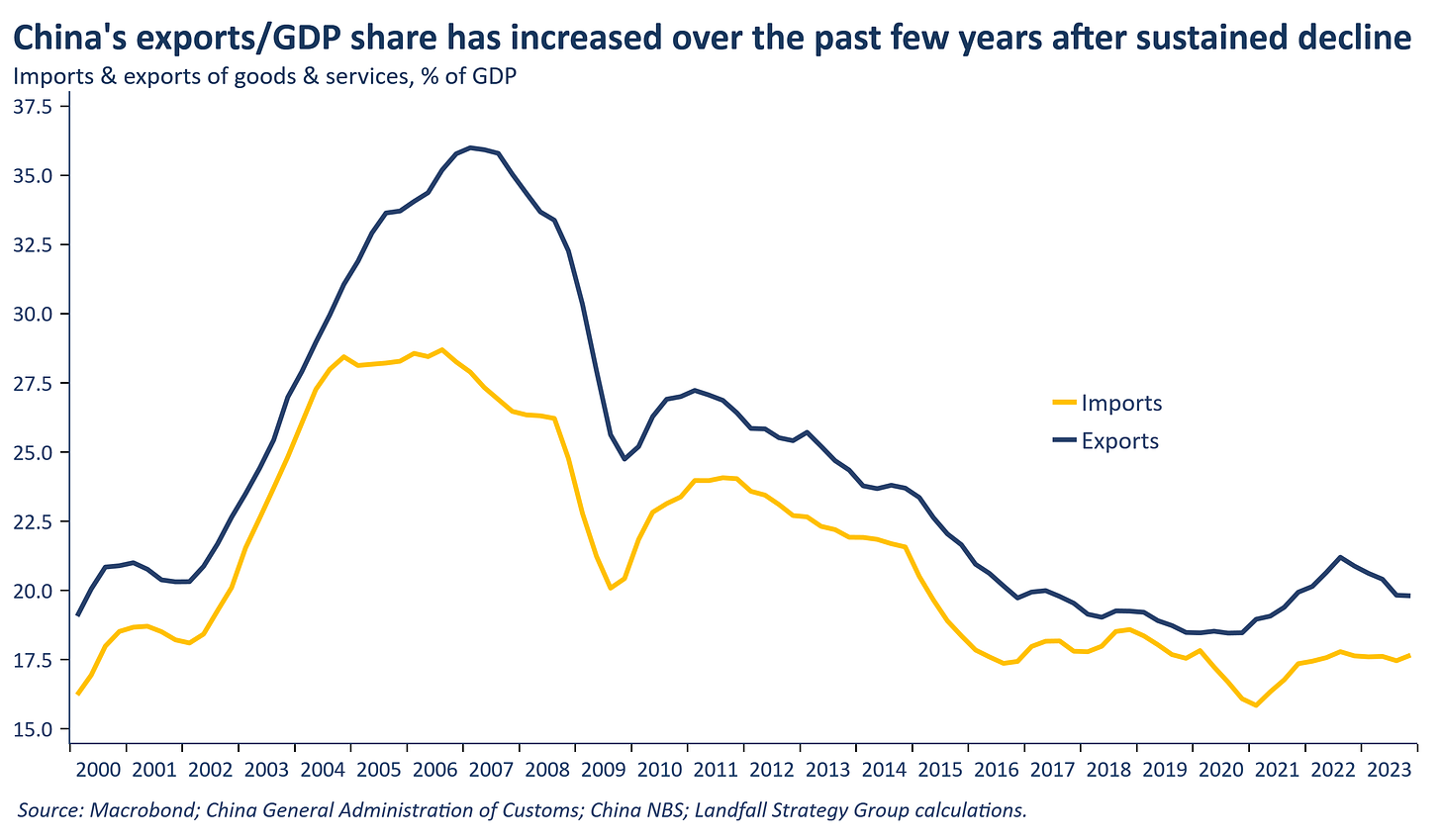

As the world’s largest exporter (~15% of world merchandise exports), China’s export-oriented industrial policies will have a meaningful impact on the global economy. After a period of decline, China’s exports/GDP ratio has increased recently, and is back to 2017 levels. Net exports have made a material contributor to China’s GDP growth over the past few years.

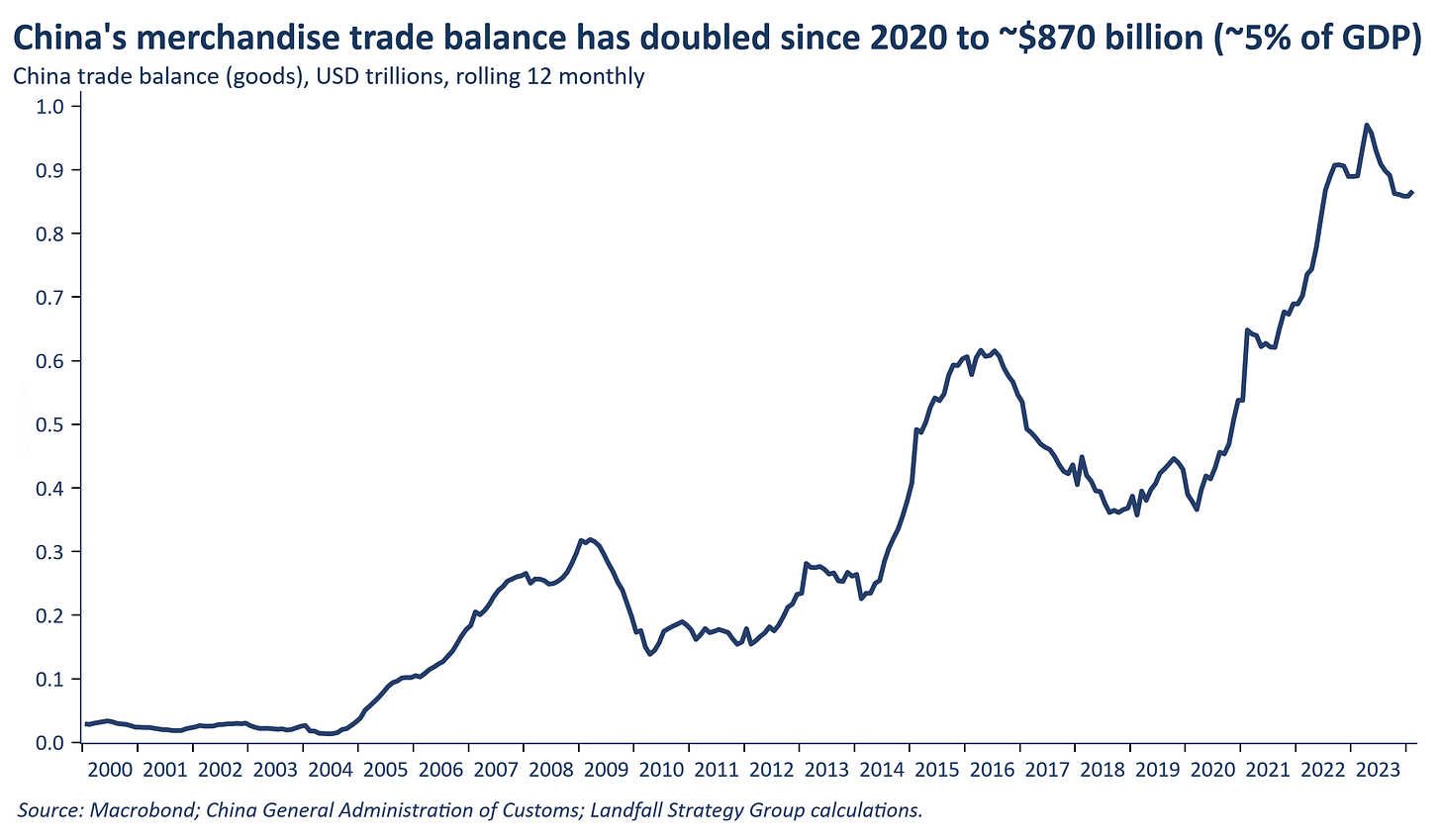

And China’s trade surplus has increased strongly over the past few years. China’s trade surplus was $870 billion in the year to February, doubling since 2020; amounting to ~5% of China’s GDP. This is at close to record levels in absolute terms. And the actual trade surplus is likely to be materially larger than the officially reported trade surplus.

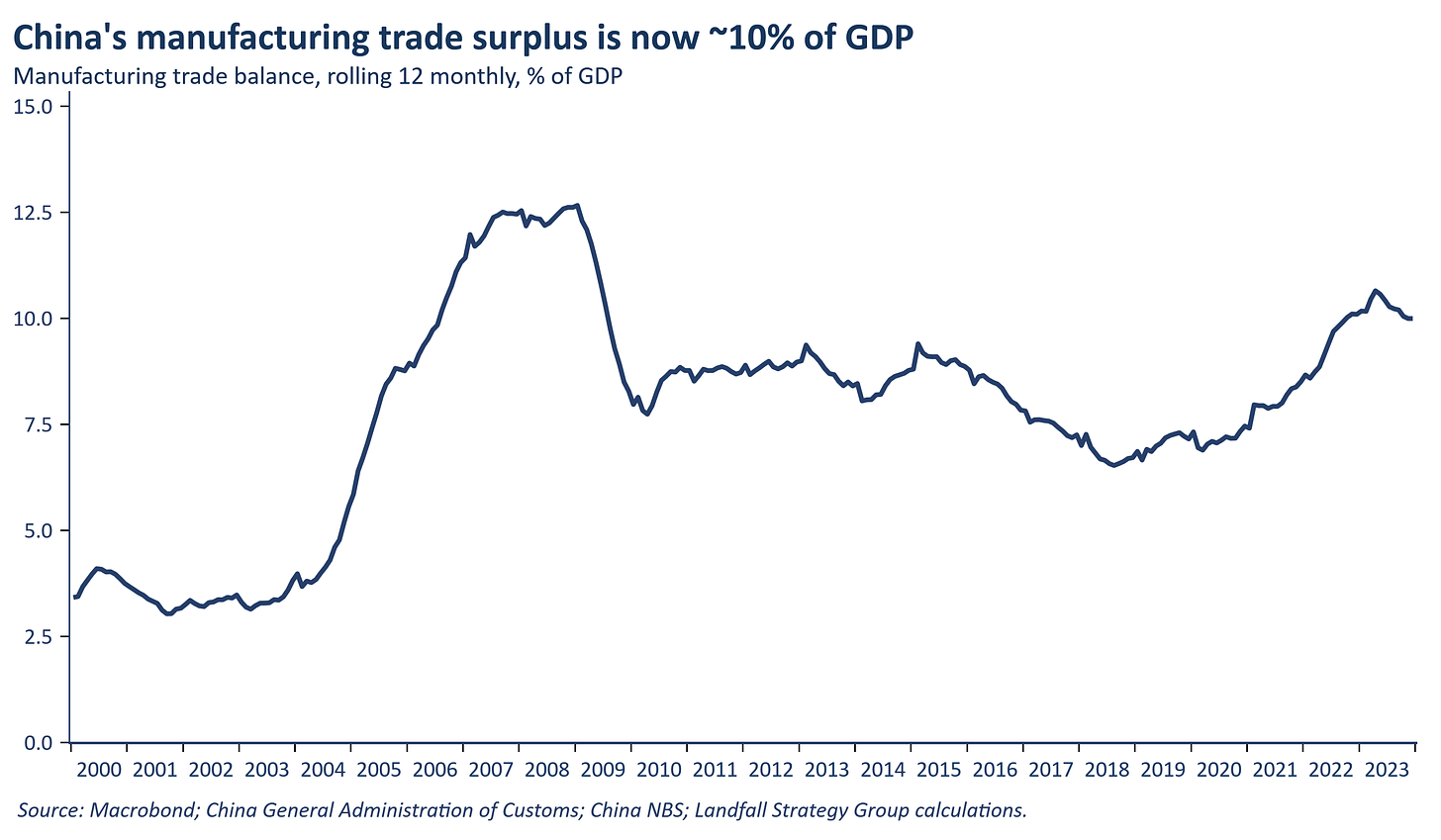

China’s manufacturing trade surplus position is even more substantial, at ~10% of GDP in the year to Q4 2023, sitting at levels not seen since 2009. This is equivalent to a remarkable ~2% of global GDP.

These substantial surpluses are unlikely to reduce soon. Although the two sessions meetings mentioned the need to avoid over-capacity, support for industrial production and technology (‘new productive forces’) is a core feature of the Chinese economic model: both export-oriented and to displace imports into China.

China shock 2.0

Some economies may see cheap Chinese imports as a welfare-enhancing, positive terms of trade shock. For example, New Zealand has a limited manufacturing base in areas in which Chinese industrial exports will be focused: cheap cars, solar panels, or other advanced manufacturing products would be an economic gain. And cheap renewable technology from China can support a more efficient green transition in many economies.

But aggressive Chinese industrial policy also creates challenges. For example, Europe’s auto industry faces intense competitive pressure from increasing market penetration of Chinese EVs. A decade ago, the European solar industry was decimated by subsidised Chinese competition, to which European governments did not respond. This time around, a more assertive response is likely: the European Commission has announced anti-subsidy investigations on Chinese EVs, and similar action is likely in other sectors. A commercial response is also underway, with European auto manufacturers considering an ‘Airbus-style’ model of collaboration to drive down costs in order to compete.

Similarly, the US is using trade policy as well as the design of industrial policy (e.g. incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act) to protect against Chinese imports. And in any case, the US import share is relatively small at ~15% of GDP.

But trade flows are like water, taking the path of least resistance. If some large advanced economies impose barriers, then exports will flow around these barriers.

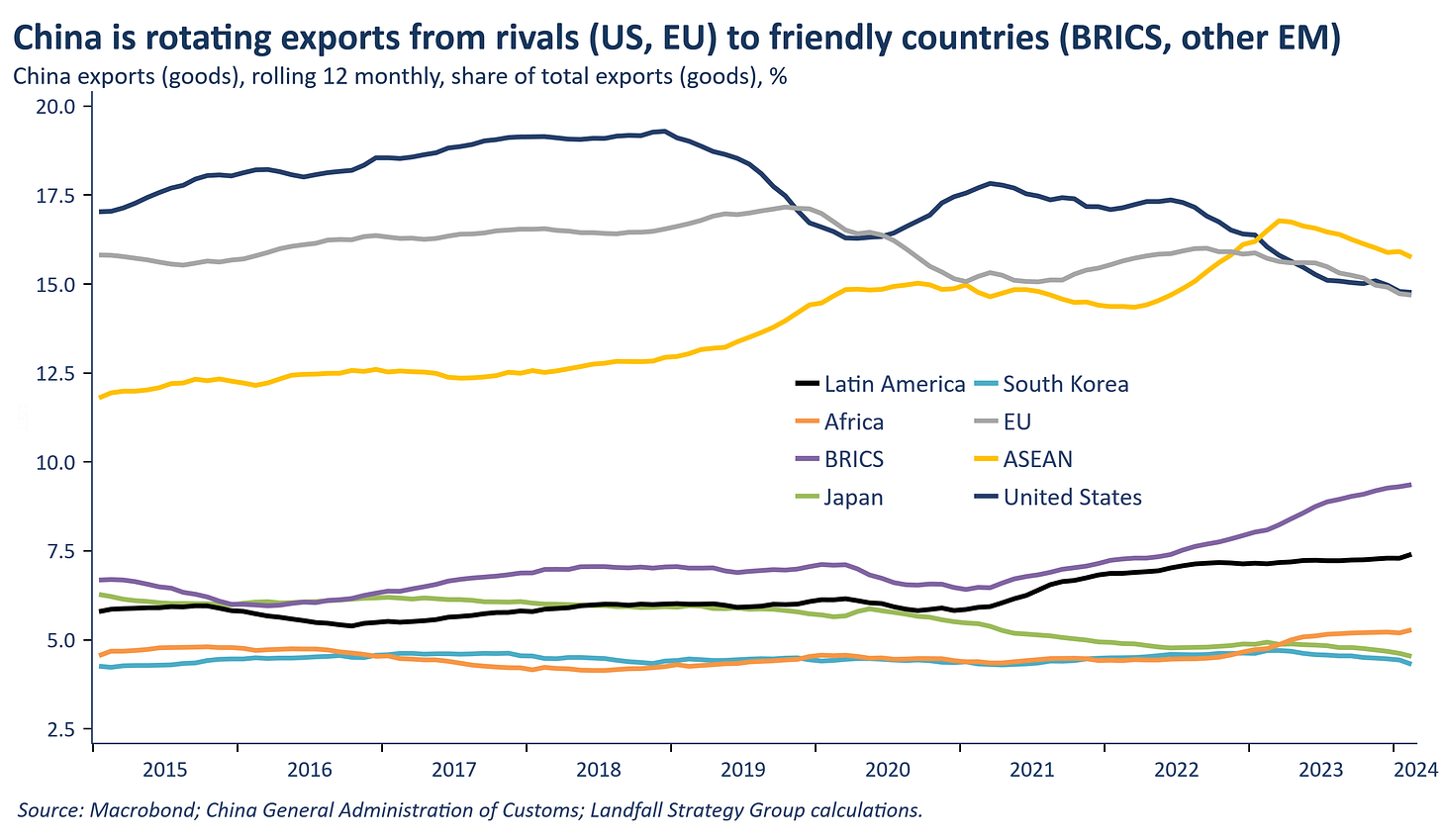

Indeed, China’s export flows are shifting towards economies that are more geopolitically friendly: away from the US, EU, Japan, and South Korea; and towards the BRICS, ASEAN, Latin America, and Africa. This will continue, as advanced economies attempt to manage down their economic relations with China for economic as well as geopolitical reasons.

Many developing countries are unable/unwilling to impose tariffs on the Chinese export of over-capacity of industrial goods, and the WTO can’t help. As discussed in last week’s note, this growing Chinese competition will reduce the ability of these economies to develop their industrial bases, further constraining their ability to undertake export-led growth (and reinforcing ‘premature deindustrialisation’).

China’s approach will generate particular challenges for developing economies, because China is aiming to maintain strong positions in lower-cost manufacturing as well as developing competitive strengths in advanced manufacturing. Many firms in low and middle income countries are facing intense competitive stress from surging Chinese imports.

China’s aggressive industrial policy will also create challenges for small advanced economies, whose growth models are built around exporting of advanced industrial goods (think Sweden, Switzerland, and others). Small economy firms will face more intense competition from Chinese industrial firms in China and in other third markets, and will need to adapt their products and business models: Danish renewables firms are an example of this exposure.

This is another vector of China-related economic exposure that economies and firms need to respond to: beyond the challenges of accessing a slower-growth Chinese market, and pressure to de-risk China-exposed supply chains, there is growing global competitive pressure from Chinese firms – many of whom are moving rapidly up the value chain.

However, there are limits to the economic contribution from this policy approach – which means that China can’t pursue these policies indefinitely. The collective size of developing economies cannot compensate for reduced access to advanced economies. Although China’s trade surpluses have been increasing with countries like India and Mexico, this group of economies do not have the capacity to absorb China’s large trade surpluses. China will need to continue to engage with advanced economies – and to strengthen domestic demand.

The ‘China shock’ from the 2000s – as China’s grew its global export market share strongly – was felt acutely across advanced economies; and contributed to subsequent political disruption. This China shock will have a different global impact because of policies in large advanced economies to de-risk from China. This will limit their China exposure, even as it contributes to a more fragmented global economy. However, emerging markets and economies with material footprints in priority sectors for China, will be highly exposed, with impacts on their growth models.

This will create political stresses, particularly across developing countries. China’s leadership position among these countries will be challenged to the extent that it is seen to be pursuing its national interest at the expense of others (in a similar way to the pushback on aspects of the BRI).

Industrial policy in China, as well as in the US and the EU, is reshaping the global economy. Multilateral institutions like the WTO are unable to manage these behaviours. A fragmented global economy is emerging, driven by the self-interested actions of large economies (and the strategic logic of competitive rivalry). This is an increasingly challenging environment for globally exposed economies and firms, and will require rapid, deliberate adaptation.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

18 Comments

Although China’s trade surpluses have been increasing with countries like India and Mexico, this group of economies do not have the capacity to absorb China’s large trade surpluses.

There is NO meaningful decoupling of global trade from China. China's trade surplus with countries like Mexico (black) and Vietnam (blue) is up massively. Those goods don't stay in Mexico or Vietnam. They're trans-shipped to the rest of the world. No decoupling, only rejiggering. Link

Furthermore, Russian oil exported to India is recycled at a higher price to Europe.

Skilling is increasingly discussing repercussions as if they were drivers.

The issue is that Chinese assets may be not safe to hold for westerners....................................................

...Or the Chinese judging by their stock market.

agree not good

The issue is that Chinese assets may be not safe to hold for westerners

Do Westerners own Chinese assets? I owned a Shanghai Top50 ETF through SBI up to 2013-14. Dreadful investment.

I saw a local Kiwi mechanic having a quality online rant about the quality of Chinese cars (especially from SAIC) recently. Sounds like those assets (ok, liabilities) may not be that safe to hold either, beyond the short term.

I don't see Chinese growth ploughing on for the next two decades like the last two, their fertility rates has just been too low and the working age population is already normalising:

https://data.worldbank.org/share/widget?indicators=SP.POP.1564.TO.ZS&lo…

Also they can't keep piling on debt like they did in the last decade becuse they'll run out of fiscal headroom:

https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/rngs/CHINA-DEBT-HOUSEHOLD/010030H…

Also they can't keep piling on debt like they did in the last decade becuse they'll run out of fiscal headroom:

H'hold debt to GDP is much lower in China than in NZ. And their savings rate is far better.

Much like Japan, their net debt is eye watering. But they have infrastructure.

Much of which, is a white elephant.

buy gold here

Lots of options, bullion, coins, miners, goldcorp certificates

Generically known as proxy.

Which is not the real thing, by definition

Ahh yawn, I've just woken up, that comment put me to sleep

It was just a dream

You haven't woken up yet, trust me on that.

Chinese do buy gold. Not just central bank purchases.

yes they encourage it, they can always steal it later as required.... harder to have a boating accident if you do not own a boat

China is aiming to maintain strong positions in lower-cost manufacturing

this implies China is aiming on compete with lower prices, which is not true. China does have plans to move up the industry food chains.

the Chinese aims here is not keep low cost manufacturing, the aim is keeping the employments stable. low cost manufactures are no long making much profits, but they do keep people employed, and socially and economically stable.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.