Aristotle was right. Humans have never been atomised individuals, but rather social beings whose every decision affects other people. And now the COVID-19 pandemic is driving home this fundamental point: each of us is morally responsible for the infection risks we pose to others through our own behavior.

In fact, this pandemic is just one of many collective-action problems facing humankind, including climate change, catastrophic biodiversity loss, antimicrobial resistance, nuclear tensions fueled by escalating geopolitical uncertainty, and even potential threats such as a collision with an asteroid.

As the pandemic has demonstrated, however, it is not these existential dangers, but rather everyday economic activities, that reveal the collective, connected character of modern life beneath the individualist façade of rights and contracts.

Those of us in white-collar jobs who are able to work from home and swap sourdough tips are more dependent than we perhaps realised on previously invisible essential workers, such as hospital cleaners and medics, supermarket staff, parcel couriers, and telecoms technicians who maintain our connectivity.

Similarly, manufacturers of new essentials such as face masks and chemical reagents depend on imports from the other side of the world. And many people who are ill, self-isolating, or suddenly unemployed depend on the kindness of neighbors, friends, and strangers to get by.

The sudden stop to economic activity underscores a truth about the modern, interconnected economy: what affects some parts substantially affects the whole. This web of linkages is therefore a vulnerability when disrupted. But it is also a strength, because it shows once again how the division of labor makes everyone better off, exactly as Adam Smith pointed out over two centuries ago.

Today’s transformative digital technologies are dramatically increasing such social spillovers, and not only because they underpin sophisticated logistics networks and just-in-time supply chains. The very nature of the digital economy means that each of our individual choices will affect many other people.

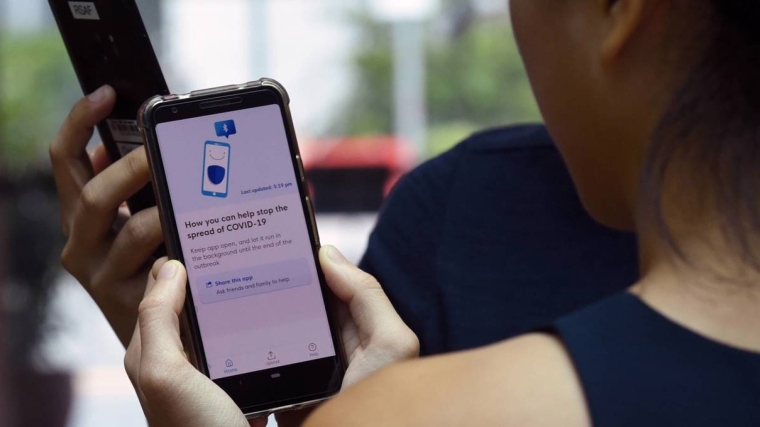

Consider the question of data, which has become even more salient today because of the policy debate about whether digital contact-tracing apps can help the economy to emerge from lockdown faster.

This approach will be effective only if a high enough proportion of the population uses the same app and shares the data it gathers. And, as the Ada Lovelace Institute points out in a thoughtful report, that will depend on whether people regard the app as trustworthy and are sure that using it will help them. No app will be effective if people are unwilling to provide “their” data to governments rolling out the system. If I decide to withhold information about my movements and contacts, this would adversely affect everyone.

Yet, while much information certainly should remain private, data about individuals is only rarely “personal,” in the sense that it is only about them. Indeed, very little data with useful information content concerns a single individual; it is the context – whether population data, location, or the activities of others – that gives it value.

Most commentators recognise that privacy and trust must be balanced with the need to fill the huge gaps in our knowledge about COVID-19. But the balance is tipping toward the latter. In the current circumstances, the collective goal outweighs individual preferences.

But the current emergency is only an acute symptom of increasing interdependence. Underlying it is the steady shift from an economy in which the classical assumptions of diminishing or constant returns to scale hold true to one in which there are increasing returns to scale almost everywhere.

In the conventional framework, adding a unit of input (capital and labor) produces a smaller or (at best) the same increment to output. For an economy based on agriculture and manufacturing, this was a reasonable assumption.

But much of today’s economy is characterised by increasing returns, with bigger firms doing ever better. The network effects that drive the growth of digital platforms are one example of this. And because most sectors of the economy have high upfront costs, bigger producers face lower unit costs.

One important source of increasing returns is the extensive experience-based know-how needed in high-value activities such as software design, architecture, and advanced manufacturing. Such returns not only favor incumbents, but also mean that choices by individual producers and consumers have spillover effects on others.

The pervasiveness of increasing returns to scale, and spillovers more generally, has been surprisingly slow to influence policy choices, even though economists have been focusing on the phenomenon for many years now. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it harder to ignore.

Just as a spider’s web crumples when a few strands are broken, so the pandemic has highlighted the risks arising from our economic interdependence. And now California and Georgia, Germany and Italy, and China and the United States need each other to recover and rebuild. No one should waste time yearning for an unsustainable fantasy.

Diane Coyle, Professor of Public Policy at the University of Cambridge, is the author, most recently, of Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy. This content is © Project Syndicate, 2020, and is here with permission.

7 Comments

Indeed, the author's note that "The pervasiveness of increasing returns to scale, and spillovers more generally, has been surprisingly slow to influence policy choices" is a useful rejoinder to the more common note struck: that returns are diminishing and that policy needs to desperately conserve what little is left of - well anything, really, if the incantations are listened to. Creative, electronic, miniature-scale stuff just doesn't take much resource anymore: a single-board computer like a Pi Zero W literally weighs a few grams, yet runs a full-scale Linux-derived OS and is thus capable of doing real work like running an online ordering website. Brushless tools have more power, smaller size, and greater longevity than the brushed versions of even just a few short years ago. And fibre replacing copper means making glass out of sand, rather than blowing the top off Tasmanian mountains containing the ore-bodies that deflected Abel Tasmans' compasses.

The paranoia with respect to contact tracing using a phone app is possibly a little misplaced, as is the privacy issue. A description of the app that is being developed this morning indicated that the data is stored on the users phone, not a central repository, and would only need to be accessed if the user tested positive for COVID. Even then the data is only phone numbers, not details of the holder of the phones, and a text could be sent to each indicating that they needed to isolate and be tested. Simple really, so some of the mass hysteria about this is wildly misplaced.

Forget paranoia, such apps are not new and have no empirical evidence that actually work.

If they have spare money then increase the budget of the health system, at least then it won't be wasted.

Sorry , but this writer has lost me completely ............ the article is all -over- the place , and even though "interdependence " is the theme / thread , she goes down all sorts of rabbit holes .

Any bugger " interdependence "............... we Kiwis march to the beat of our own drum , have pretty much done our own thing without any help from outside , and we are doing just fine .

When it suits us we will revert to our interdependence with the Aussies , but not before

In the end she is just trying to sell tracking apps.

I agree we are all interconnected, but that’s not news and all human group activity is interconnected. But that doesn’t make it bad, weak or a problem to be fixed.

Many awesome things could never have been achieved without the so called vulnerability of connectedness. Indeed, the very freedom with which the writer argues against it was purchased through highly connected group action.

Privacy is just as important as it has always been, because without privacy there is no true freedom.

But putting privacy aside, the reason we shouldn’t waste time with tracking apps is that there is no empirical evidence they actually work. They produce mountains of false positives whilst introducing all kinds of security problems.

Whatever budget we have for such an exercise should be given to an under funded health system so it doesn't get wasted.

This is a case of a technology trying to find a problem to solve.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.