By David Slack

The idea sounds improbable in hindsight. Down here in the South Pacific, as far from London in a leaky boat as it’s possible to go, we decided to make a living out of growing food for Britain. But it worked. We would send them lamb, and butter, and wool and other goods that would have been familiar to the Romans. They would send us money. Our little nation at the far end of the world steadily grew.

Over time, we would lose customers and scramble to find new ones, but we kept on growing, and now, here we are, 5 million souls and a GDP (gross domestic product) of $300 billion. Through it all, the fundamental scenario has remained more or less the same: down here at the bottom of the world, we make a living from turning grass into something the world might buy.

What could possibly go wrong? From time to time, the world economy shows us. We’re vulnerable in the way we have been from the beginning. We’re not diversified enough to be able to just sit out a global cataclysm and fend for ourselves. We need things the world makes that we do not. Pharmaceuticals. Face masks. The new iPhone.

Most of all, right now, two vulnerabilities weigh on us. Tourism, and supply chains.

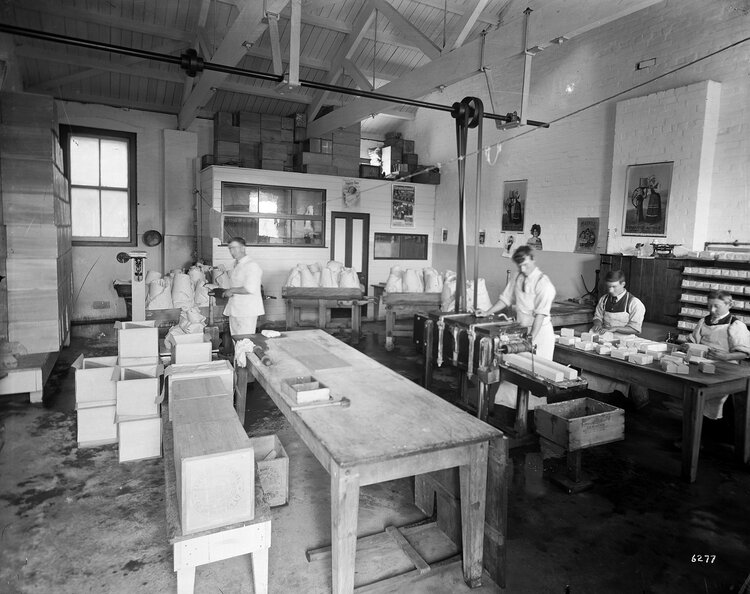

Interior of a dairy factory, early 1900s. (Alexander Turnbull Library, reference 10x8-1145-G)

Tourism and supply chains

The first of those is already painfully clear. Air New Zealand has most of its fleet parked. Tourist businesses have no customers. The borders will be shut for a long time. It’s a $20 billion industry employing directly or indirectly possibly 300,000 people, and it’s more or less paralysed.

As for the supply chains, that’s more of a potential disaster playing out in slow motion. Globalisation and open borders brought us the beauty of the global supply chain. A thing could be made in one country, bringing together elements sourced from twenty factories across the world. It could be made just in time and on time, every time, right up until the day borders closed and economies shuddered as nations went into lockdown—suddenly, we are confronted with some not-great prospects.

When the doors open again, will all those factories still be there? Will those parts be available, and will there be a shipping line to carry them? In the post-COVID-19 just-in-time economy, will those packets and pallets be available when we need them? Who will supply us with masks and ventilators and PPE (personal protective equipment) if we need them?

Now that the supply chains are in question and our borders are closed to visitors, could this be a time to reconsider the notion of greater economic self-sufficiency?

Self-sufficiency in the 1930s and 1940s

We have passed this way before. The Great Depression of the 1930s brought misery: vast unemployment, a world contagion of doors closing to trade, and financial collapse. If you lived through that, you naturally looked for ways to become more self-sufficient, to insulate the country from further economic harm. And so from the 1940s, New Zealand became a protected economy. The aim was to foster manufacturing of a wider range of goods and products, using import licences and tariffs to give local manufacturers a leg up and protection from competition.

How did that turn out? Pretty well, for a time. The ensuing decades saw many new factories producing many new goods: fork-lift trucks, water-jet engines, forage harvesters, Axminster carpets, wallpaper, aluminium sheet and foil, wood screws, glucose, dextrose, instant coffee, television tubes and tyres, to quote just a few from this roll-call.

Local manufacturers who are seen today as potential innovators had their beginning then: electronics company Tait, making two-way radios; Clearlite Plastics making plastic products, PDL making plastic, electrical and consumer goods.

These factories were mostly small affairs by international standards, except for the ones processing primary produce—freezing works, dairy factories, and later, aluminium smelter and steel mills, and pulp and paper mills. But by the end of the 1950s, the 5000-odd factories of 1930 had grown to nearly 9000, and put on nearly 100,000 more jobs.

Cutting room at Lane Walker Rudkin, a Christchurch knitwear factory, 1940s. (Alexander Turnbull Library, National Publicity Studios Collection, reference 1/2-034150; F)

1950s to 1980s

This was not a merely reflexive protectionist response. There was a long-term strategy supporting it, championed in particular by Dr Bill Sutch as secretary of industries and commerce from the end of the 1950s. Replacing foreign imports with domestic production would be an initial step towards a more industrialised, diversified economy, manufacturing not only for the domestic market but also for export, adding value to primary produce. The aim was to develop an economy of greater technical breadth and capability, supported by training, industrial design, technology and research, and infrastructure.

How well did they do? On the one hand, New Zealand went through the strongest export diversification of any OECD economy between 1965 and 1980 by product and destination. On the other, we remained lopsided, still primarily a primary producer.

The late 1970s took things a little further. Oil price shocks had brought inflation and economic turmoil. Various expensive projects were instigated under the banner Think Big with the aim of reducing our reliance on imported energy. We would use electricity and gas to reduce our reliance on oil. The projects came on stream more or less in time to see world oil prices fall and make the projects look like a vast waste of money.

Changes in the 1980s

This also coincided with the change of government in 1984 that put New Zealand into the global slipstream of free market reforms, economic liberalism and globalisation that threw open borders to let competition thrive.

Our local protectionism was now examined through a new lens: these local operations, how good were they really? Were they efficient, or were they costly and rule-bound and lumbering? Were we stuck in some kind of unionised Polish shipyard? What sense did it make that car manufacturers would disassemble a car, put the parts in a crate, and send them out to New Zealand to put it back together in a Porirua car plant? And what sense did it make to be assembling TVs and radios, or to be making shoes and clothes here, when we could be buying them for so much less from somewhere in Asia?

The arguments in favour of competition and globalisation were put compellingly; Finance minister David Caygill said you could theoretically grow bananas on the side of Mt Cook with a decent glasshouse, but that didn’t mean to say you should.

Arguments in defence of the self-sufficiency of our economy or the protection of jobs were trumped by arguments about competition making us more prosperous. If someone could offer those products or services at a better price, we should let them do that and play to our own competitive strength.

And so from 1984, import licensing was dismantled, subsidies removed, and tariffs progressively reduced. Many factory industries struggled to compete, and folded.

What were left, in the end, were chiefly export-viable manufacturers: in plastics; organic chemicals; paper and paper products; electrical and electronic goods; and machinery. This might be the place to first ask about the possibilities of expanding local manufacturing.

Those changes of the 1980s carried us into the current settings of free market and comparative advantage, and extensive and elaborate global supply chains.

Looking forward

Life’s enduring lesson is that in curing one problem, you often create fresh ones. Have we made ourselves too dependent on a world from which we can be cut off? Has the pandemic demonstrated to us that certain goods and services matter too much to ever be out of reach?

If we cannot ever hope to be entirely self-sufficient, would it not at least make sense to secure a greater degree of self-sufficiency than we currently have?

If the wait for a vaccine could be long, could it be time for us to explore the possibilities for securing a greater degree of self-sufficiency, if not within New Zealand, then at least in a common market with Australia, for manufacturing in the immediate vicinity and for a shared tourism market? And how might that work?

In the next blog of this series, we’ll explore what self-sufficiency in New Zealand might look like in the short term.

This is a re-post of a blog article. It is here with permission.

34 Comments

I have an axminster carpet. Tough as nails. Polishes up pretty good considering the hiding it has taken. Shame it never really moved with the times.

We had Axminster too in a rental. Went the distance in perfect condition for almost 40 years. It was only defeated eventually, terminally, when the tenants invited 20 additional family members to come and stay, plus a few dogs. The children pissing on the carpet (not the dogs) were the final straw for that hideously garish carpet.

This is one of our more independent, more original commentators. And the piece promises more.

But unless it addresses resources (finite, renewable and sinks) and energy (including EROEI and entropy) his series will fall short. In closer detail, he has to challenge 'the economy', 'productivity', GDP, growth, and in futher minutae, things like 'child poverty' (really child lack of access to resources/high-EROEI energy).

Still and all, this - along with the Carr letter and coming webinar - is the discussion we need to be having. Kudos to Slack.

I agree...

Deregulation hasn't worked for NZ, and can clearly be shown in our declining standard of living. Roger Douglas, Caygill and Prebble were the biggest clowns out, and corrupted by big business. Their road led to ACT; say no more.

We needed a balanced approach, with the government retaining control of core monopoly assets, so the private owners couldn't abuse their power. Private (especially listed company) ownership objectives are completing different to public, where short term profit maximisation for executives and margin traders is the game. Government (though you do wonder with some past administration) has to govern for the greater good of NZ inc, and think about long term sustainability with their policy directives.

Overseas banks controlling our market has been the biggest thorn in our side, and NZ inc is now paying for it in the high cost of living these banksters have facilitated. No other country allows their banking system to be dominated by overseas banks in the way we do. By now, everyone knows ex politicians have aid and abated their profits; and I'd see them locked up yesterday.

The government needs to focus on bringing down the cost of living for the masses, and if this means reducing profits taken out of the country by overseas investors, I'll all for this. This could and should mean the government entering the market dominated by few players where the profits are over the top, to provide competition which is currently lacking. Banking, Supermarkets, building and infrastructure suppliers would be a good start....

As I am only 27 I have only heard about recessions/depressions of the past.

I've been reading up a lot more lately (a good time to do it - during lockdown). This was a great post to highlight how we have reacted in the past.

The idea of a trans-tasman bubble and economy sounds interesting to me. It seems to make sense. But as I am not an economist or an anthropologist for that matter, I am un sure what negative ramifications it might create. I wonder... If we have a shared economy with the Australians (say an Australian dollar??) do we risk giving up some our a lot of our sovereignty?

I am genuinely puzzling this out. Please correct me (and explain) if this idea is completely preposterous.

My concern is more around the economic disadvantages NZ would have from a trans-Tasman common market. In comparison to the Aussies, we seem to have a lower productivity, a larger infrastructure deficit (which is likely to widen over the next few years as they ramp up works and investments in public projects and we still lack political will to get anything off the ground), fewer skilled workers and lack economies of scale in common industries, except perhaps dairy.

Can we get past this nonsense about ' productivity' please?

Labour is less than 1% of all work-done globally. Fossil energy provides the main portion of the other 99%. And you don't produce output, without energy. No, not even two or three moves removed.

So you're up against thermodynamic limits (to efficiencies of FF use) and you're up against reducing EROEI sources remaining.

So of course your productivity will tail off, plateau, then reduce. Can we get past this scratch in the record, maybe? Economics, as taught, has much to apologise for; the flawed meaning of 'productivity' is merely one such.

When the rest of the world operates with this as a constraint, it will be relevant. But they don't. We could kneecap ourselves for no real advantage while the rest of the world carries on their merry way.

I wouldn't worry about it. Economists are wrong 99% of the time anyway. And the older you get, the more you realise everyone is just making it up as they go along. History is valuable but only hindsight is 20/20. No one should apologise for their views.

If there was one thing Muldoon did well it was to illustrate through, what he saw as being necessary to protect the status quo, his policy of socialism, subsidies, tariffs, freezes, that NZ’s traditional modus operandi had come to a shuddering halt. The Lange/Douglas ensuing reforms were of dramatic impact on everyone. Farmers lost subsidies and farms. Homeowners and families had realistic budgets blown out of the water by 18% mortgages. But more tellingly two seriously important aspects were then launched. The rise of the corporates and the rise of debt. The established lending restrictions, the corset, of the RBNZ were relaxed and credit cards and other personal finance, eg vehicles, hit the streets running. So how much of our self reliance as a nation has been compromised by individuals having to rely on credit to exist and then, on the other point, the dominant position of certain corporates for instance, the Fletcher group controlling the supply and pricing of building products on a very large scale.

18% mortgages would have been horrible. Thankfully inflation was running at 10 - 15% at the time to erode the value of the debt. Try doing the same again today. Infact, if we are heading into a period of deflation what happens to peoples incomes in relation to their mortgages?

Therein lies the rub. Modern mortgages are basically unrepayable unless you have thirty solid years of work lined up, no redundancy, no time off to have kids and no having to accept lower wages in order to keep money flowing in.

The recent drop to 80% for many private sector workers (with no assurances things will ever return to 100%, in many cases) shows how easy it is to devalue labour in an already-low wage economy. Yet your mortgage doesn't get impaired should you find yourself in any of the above situations. All of the risk, barely any of the upside.

Muldoon seems to get a historical bashing regularly. As a late teen in the early 80s at varsity my rent was frozen and food prices stabilised. I lived on $44 per week with some very small savings from summer work, and parcels from mum. And I hitched everywhere. I just remember being greatful to Muldoon, as the late 70's were pretty tough. I used to do the food shopping with mum. Prices went up in leaps and bounds. Mum and dad had an amazing vege garden and plenty of mutton thankfully. Clothing was expensive. Good jeans could be as much as $40, I pay $29 now at the warehouse. NZ really was a different place back then. The price of clothing and shoes was particularly horrendous.

About the first four years of his government were fine, but the world was changing, Reagan/Thatcher, the oil crisis etc, and hopelessly and haplessly he tried to legislate to banish that change. You know if hadn’t been for one Mr Jones, Muldoon might well have got a fourth term, such was his popularity with traditionalists, reactionaries if you like. Speaking of Bob Jones, recall one of his articles explaining the rise in spending power, you refer to jeans he exampled gum boots. As a child gum boots in our family were as expensive as they were precious and handed down. Nowadays they are a seasonal disposable fashion item.

It only required one income to buy a house and to support a family though and there were no such things as food banks and people living in motels.

Yes but back then people survived because they were a tough as nails, prudent generation. Why when they were children, milk came in a glass jug and not this plastic throw away crap they introduced when they became adults we see today. Today's generations should be grateful for cheap flat screen tvs and ipods, so what if home ownership is out of reach???

You talked to any school teachers lately about what those flat screen tv's and iphones have done to the brains of school aged kids these days?

I have multiple teachers in my extended family. They swear kids are becoming worse in terms of intelligence and attention spans and issues like ADD, anxiety, depression etc.

And home ownership is important to make people feel established, gives security and feel like they're part of society/community. Otherwise you feel as though you are a slave within your own community, which you are to the landlord class.

Stuff was a lot more expensive but it was better made, better looked after and able to be repaired. The range of what you can buy now has expanded enormously and it's relatively dirt cheap. (Some due to globalisation, and some due to advances in technology).

The environment's been the main casualty.

Cars were expensive, needed overseas funds to secure a new one. But they were unreliable too. Recall sighting a brand new Vauxhall Cresta in the show room, a drip tray to catch the oil. We started out on Model A’s handled all the repairs and maintenance ourselves. Not as dangerous though, couldn’t get up to the speeds of those available first time up today. We had a boy at primary school, turned up with handkerchiefs made from old sheets. For our under 7st rugby he came with his sisters netball boots, to which his father had glued lumps of rubbers as studs. None of us teased him. He is of only two of my school year that went on to play for Canterbury.

The 70's wasn't all beer and skittles, reliability of machines and appliances...didn't even exist. Everything broke down and constantly needed repairing. The mind boggles. Political leadership has steadily deteriorated over the decades, no doubt about that, the current coalition are a step back from total disaster but this country accepts poor leadership far too readily. This nonsense about a transtasman bubble is just another cluster f#ck in the making, the Aussies will just rip us off. Think of who owns Countdown Supermarkets...get the picture?

Any thoughts if current NZ is better or worse than say NZ prior to 1980's? Obviously looking to the thoughts of the elders of interest.co.nz to give their perspective..

Well, I'm old enough to count. Born '55.

NZ was more resilient, more able to fix what it had, more adaptable and less specialist. It was also more egalitarian, and a murder was a one-off, talked about for years. It was a nicer, more caring, less selfish place. But the selfish were there, and in the intervening years have had more and more power. The removal of democracy in Canterbury will be the only remembered legacy of the Key govt, in 20/30/40 year's time (how many remember Nordmeyer and Nash? All that is referenced is 'the Black Budget').

Now I see more indebtedness, less useful skills, less all-roundedness, less learning, more assuming, more sense of entitlement. In all respects, a society worse off. 5G a society does not make.

Good Lord, I'm an elder millennial and I can still remember shops being closed on weekends. Up until recently this was still the norm in places like Taupo. Main street NZ closing at 4:30pm instead of 1pm is a very recent development.

It depends on your perspective. My family was lower middle class. We seemed to have enough to survive on, but my children would find it very austere. Tech was expensive e.g. K9 Colour TV was the equivalent of $5,000. Cars were expensive. Clothes were expensive. In fact everything was expensive compared to today, except housing, but even then mortgages were hard to come by. My grandfather had a long list of unacceptable partner traits for his children: religion, ethnicity, club membership etc. I wince even hearing them spoken about. It was a society of stay in your lane and had many hidden secrets. I have good memories of most of it but I wouldn’t want to live in that environment again. If it hadn’t been for Rogernomics I would be a lot poorer.

Ok so the warehouse jeans at $29 are hit and miss. Some of the material is really bad. So I might buy 2, to find 1 good pair. But then I will go back and buy a couple more of the good pairs and stock up.

The cotton itself was much better back in the day. Generally mens clothes now arent too bad. But a good womens cotton shirt say is very hard to find. Let alone girls clothing. Take a walk down the girls aisles looking for something warm, then do the same down the boys aisles. Its shocking. Good warm stuff for boys. Pretty pink rubbish for girls.

As for the 70s mum made most of our clothes. Most mums had to be good sewers and knitters. We had lots of great warm jerseys, that were passed down between us kids.

Car safety was hilarious. We use to do trips down to the grandees. All of us would be cuddled up in the back seat with blankets and pillows. I remember nearly having an accident in Auckland on the way through and us kids all hitting the front seats. No seat belts. Even in the 80s I had friends that would chuck the kids in the back of the canopied holden ute to sleep on their way to and from rural parties. They always got home safe.

The early 90s was very bad for unemployment. In fact all thru the 70s 80s and 90s there was very little in part time work. Teenagers found it difficult to earn a bit extra. The so-called gig economy has been a boon for the younger generation. If you want to work its there for you. It really was a struggle years ago. I remember in the 90s the Rotorua paper would regularly have only 2-3 jobs advertised. And that was the only place jobs were advertised.

High interest rates and inflation had been beaten into us as being normal. So to currently find my farm loan sitting at 3.3% yesterday was ....unbelievable. I never ever thought I would see that.

I had a conversation with my son earlier. I heard some advise from Peter Beck(Rocket Lab) Now is the time to leverage yourself into something. My son who is a bit of a goer, he has bought some land and is working hard. Makes a good quid. Came back with why? That money maybe isnt that important and perhaps we should be all enjoying our lives more. I think it was a wise bit of advise to his mum.

Australia has two distinct advantages that NZ will never overcome. They could, but won't.

It's called transport. Or distribution.

a) Rail. Australia chose to go with wide gauge rail which carries the heavy load of moving freight around the country during evenings. Plus high speed passenger trains 200 kph. Very well patronised. Facilitates commuting from Bendigo, Ballarat and Geelong. Current resurrection of the NZ commuter service between Hamilton and Auickland takes 2 hours to travel 80 kms. The AU rail network has been upgraded with continuous welded rails and wooden sleepers replaced with concrete sleepers. NZ cheap-skated and went with narrow-gauge rail with a maximum speed of 80 kph for passenger rail. The rail network has largely been mothballed. What remains has been starved of mainenance

b) Highways. Have a read of the history of the duplication of the Hulme Highway 840 kms between Melbourne and Sydney. Took 50 years to complete. Duplication works on the highway began in the 1960s and concluded in 2013. The entire route between Sydney and Melbourne is now a dual carriageway. The Hulme Highway, particularly, and others are used by truckers to move food and small goods overnight. Harvest mangos and Lady Finger Bananas in Queensland today, available in Melbourne tomorrow.

It's called "Think Big" which has a dirty name in NZ

And Mines. 40% of world's Li comes outta Greenbushes and Mt Cattlin in WA, Cu used to come outta Mt Lyell in TAS, Pb is refined at Port Pirie SA, U/Cu at Olympic Dam (also SA). Sn from Renison Bell (TAS). None of this is available in NZ....

The missing link is .....

From the late 1800's until 1973 NZ sold most of its rural-based production into the UK and we grew rich on it. During that period NZ was in the top quartile of wealthy countries, all on the back of a guaranteed market from a benevolent empire. Then the UK joined the EEC leaving NZ to fend for itself. Mind you, NZ had 10 years notice that it was going to happen. Then the 2 oil shocks happened. Then things got tough

The article misses entirely the lack of historic self-sufficiency in many raw materials. The author rhapsodizes over "fork-lift trucks, water-jet engines, forage harvesters, Axminster carpets, wallpaper, aluminium sheet and foil, wood screws, glucose, dextrose, instant coffee, television tubes and tyres" without understanding that even in terms of the metals involved - Cu, Al, Sn, Pb, or the rubber, cotton, and oil for the textiles, tyres and plastics - NZ was not and never has been 'self-sufficient'. So there's considerable confusion here between raw materials and finished goods.......and we long ago perfected the art of turning Wool into Copper, Meat into Tin, Milk into Rubber and so on via Exchange. A true 'self-sufficiency', also known as Autarky (or as a Lincoln lecturer noted to me ' a Siege Economy'), has a long and generally inglorious history. That's not to say that there isn't a middle path. But at least we should get our terms straight....

Agreed Waymad.

One can stock up on all kinds of things, but if they're imported or their raw materials are, the clock is ticking as per 1959 De Soto's in Cuba.

Yes, almost everyone misses the point on this. There's no point manufacturing things here as we need to import the raw materials, and we refuse to extract any raw materials we could produce (virtually banned drilling or mining). Its the most pointless argument, increasing energy production for large scale industrial production is also difficult (and not likely cost effective) with renewable energy unless we build more dams or expand geothermal. Farm, horticulture and wood products value adding are likely the only exceptions but we are already "self sufficient" in those and economics decides if they are viable for export.

We are much better off importing finished products than importing raw materials and making them un-competitively into products.

An important factor is missed here when working out what is made in New Zealand.

Ownership.

We saw entrepeneurial people start industries, grow and prosper. But ownership passes in time from the family. Types such as private banking, or corporates take over.

In time the activity goes offshore.

If the ownership remained local, and or connected, much would stay in New Zealand.

Lets recognise the influence of "ownership" in this equation. Or to use "ownership" as a method to retain local enterprises.

Two points.

Tahi...Anyone who is Tangatawhenua should not encourage closer ties with Australia, it is even more racist than Aotearoa.

Rua...due to the inherent racism in Aotearoa, subsequent to the collapse of the terms of trade in our economy when the UK left this country high and dry and joined the EU...NZInc has failed to materialise, due in large part, I feel, the failure to realise the economic potential of Tangatawhenua. I am here yet you do not see me.

Got a daughter in local government, she constantly comes up against co workers who simply see no reason to engage with local iwi. She can see it's obvious as a way to progress and that in ten years will pay real dividends.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.