By Bernard Hickey

This economic recovery feels like a Claytons Recovery: the economic recovery you're having when you're not having an economic recovery.

It feels different this time around. Unlike the recoveries after slowdowns during the decade from 1998 to 2008, this one doesn't have any bounce or snap in it. It is distinctly underwhelming.

When you walk down the main street every second shop still has a 50% off sign and every bank is offering to take your money in as term deposits rather than offering to lend you money cheaply. Restaurants are not full. Hotels are quiet. Houses are not selling.

Many consumers and small businesses are starting to get an uneasy feeling. What if the economic recovery we've been in since early last year isn't like the others? Why is it different this time around? What happens next?

I think we face a decade or more of slow, grinding deleveraging of debt that presses down on economic growth rates, employment and asset prices, particularly house prices. When I mean we I mean New Zealand and the other developed economies with household sectors that took on a lot of debt to pump up house prices and go on a consumption spree.

This deleveraging is inevitable. It cannot be delayed or deferred or tricked away or ignored. It has already started and is acting like a glacier grinding its way down the valley. It will carve out a different economic landscape. It will turn our economic recovery from a V shaped one into a U shaped one. It will happen slowly and appear to go on for years.

Those with very high debts will try to tip toe out of its path or hope it melts before it gets to them. They can't get away and it won't melt. This deleveraging grind will change economy from a housing market with a few things tacked on into a more balanced economy driven more by exporting and the productive sectors than by construction, retail spending and consumption.

For many this may seem like a sobering and overly pessimistic forecast, so here's a few factoids to chew over.

I want to use the following 10 charts to explain how this force is inexorable and what it might mean.

Chart 1. Our overseas debt is too high

Chart 2 - Most of this debt is household debt and it's just as high in other indebted countries

.gif)

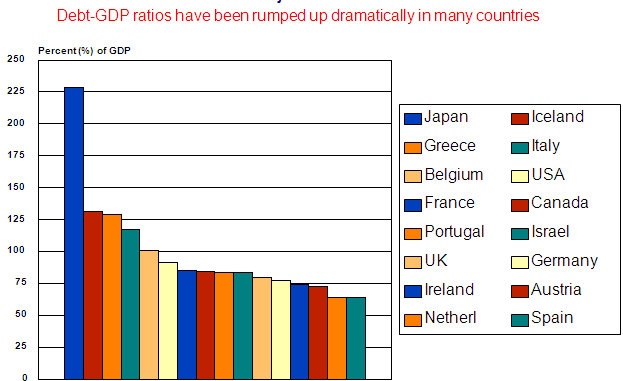

Chart 3 - Other countries such as Greece, Portugal and Spain have debt/gdp ratios that are as high as NZ

Chart 4 - Debt globally is very high and will bear down on economic growth. US debt is much worse than before the Great Depression.

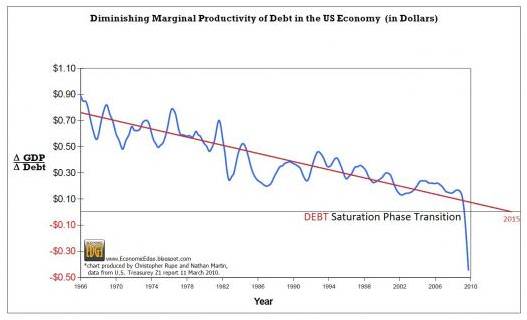

Chart 5 - US Debt has reached saturation point.

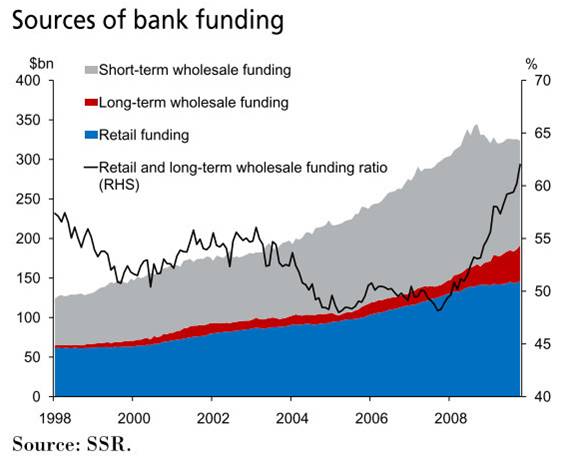

Chart 6. NZ banks are having to raise more expensive funding, which is pushing up interest rates. This combined retail/long term ratio (the black line) is set to go to 75% in 2 years.

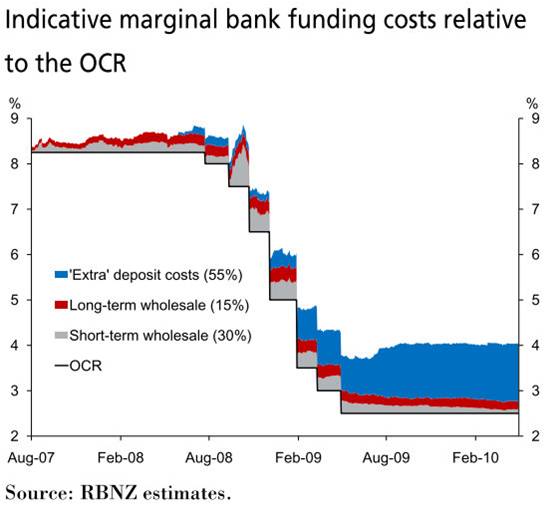

Chart 7: Bank funding costs have risen, pushing up relative interest rates and discouraging both borrowing and lending.

Chart 8: New Zealand money supply is already contracting faster than it has done in recent history

Money supply

Select chart tabs

Chart 9: NZ mortgage approvals have been falling for more than two years, accelerating the deleveraging.

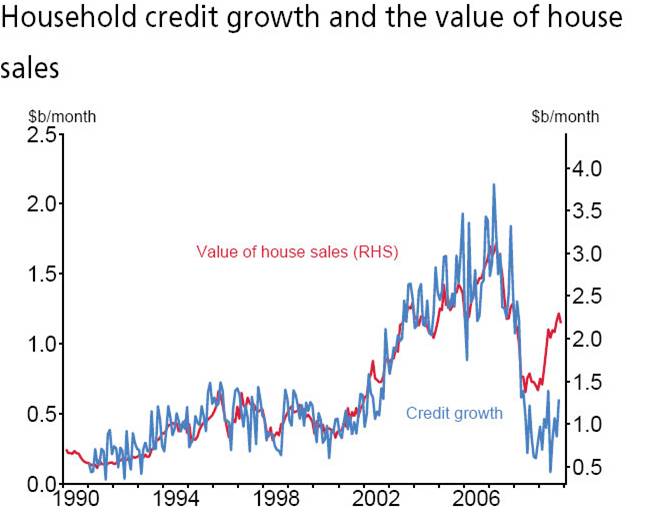

Chart 10: New Zealanders are already saving more. This chart shows housing market turnover (red line) has now broken from housing credit growth (blue line) and the gap is households saving. Borrowers are paying more than they need to and some homeowners are downsizing to repay mortgages.

Deleveraging can be done in a couple of ways

We can reduce spending and save more, which we have already started doing. Or we can stop borrowing more and let our incomes rise to reduce our debt to income ratios. Or we could have a forced reduction of debt where the lender forgives debt and takes a loss that hits their shareholders.

The last one isn't going to happen without some sort of financial catastrophe in Australasia, which is very unlikely. So we face the slow grind of reducing debt and constraining spending while building incomes.

Banks are restraining lending, real interest rates are rising and the money supply is contracting. The Reserve Bank is ensuring banks are more careful about how they fund their lending, the banks themselves are passing on higher funding costs and borrowers have reached a debt saturation point.

Given we face a relatively low inflation environment, we can't rely on inflation to do the work for us. It will be a long and hard road. It will be very tough for retailers and for anyone expecting house prices to keep rising.

We'll now have to produce for living and spend only what we earn, or even less.

Your view? I welcome your thoughts and comments below

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.