By David Skilling*

After several decades of integration and opening up, recent developments suggest we may have reached the high water mark of China’s engagement with the global economy.

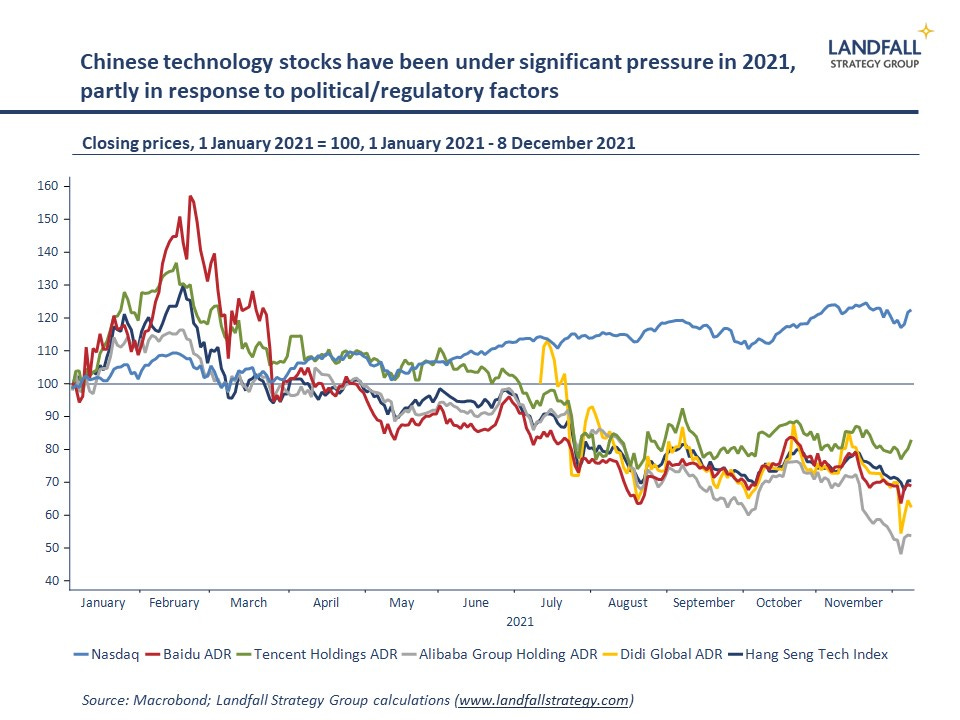

As examples from the past week or so: Didi announced its delisting from the New York Stock Exchange after its June IPO, with expectations of more Chinese delistings to come; China deleted Lithuania from its customs system (effectively banning its exports), and is organising a corporate boycott of Lithuanian firms; and China is preparing new restrictions on foreign investment in Chinese technology firms.

Until recently, economic tensions with China have been more of a shadow war. Despite the noise of trade wars, trade and capital trade flows between the West and China have continued to grow to record highs.

But political choices, both domestic and international, are now shaping economic behaviours to a much greater extent. China has an increasingly domestic focus; and the US, the EU, and others are taking a tougher stance on engagement with China.

Things aren’t like they used to be

These indications of a turning point in the nature of China’s integration into the global economy are particularly striking because they come on various significant anniversaries of China’s opening up.

50 years ago in 1971, President Nixon made a shock announcement of a trip to Beijing (undertaken in February 1972), which he subsequently termed ‘the week that changed the world’. As well as changing the shape of the Cold War, the breakthrough meetings between Nixon and Chinese leadership created a supportive environment for China’s subsequent reform and opening up. But Xi Jingping represents a clear break with the policies initiated by Deng Xiaoping.

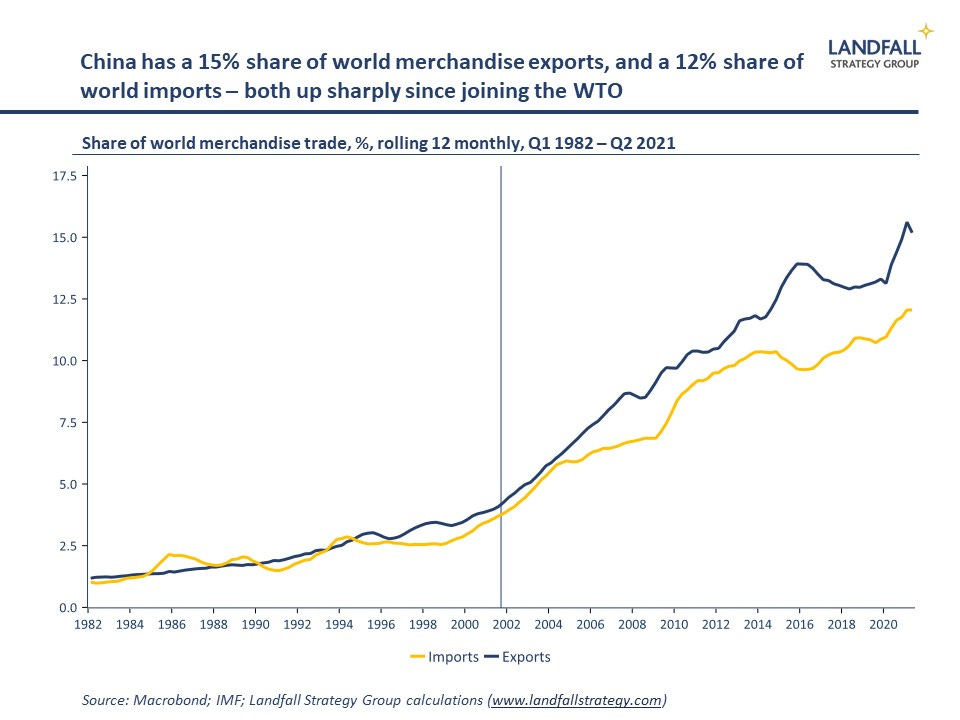

And 20 years ago tomorrow (11 December 2001), China acceded to the WTO. WTO membership formalised China’s entry into the global economy, and accelerated China’s integration process.

Since 2001, China’s share of world goods exports has increased from 4% to 15%. And it has become the largest export market for many countries. China has been central to the process of intense globalisation, becoming the factory of the world: exporting deflation, competition, and labour market disruption around the world.

But China is moving away from an export-oriented growth model. Part of this transition is inevitable as China has developed and because of its very large domestic market. Further declines in its export and import shares of GDP are likely. But this transition has been reinforced by recent political choices to strengthen self-reliance and reduce external exposures.

And under President Xi, China has adopted a more confrontational international political stance with a more inward-looking focus. China’s tough approach to Hong Kong provides an example of the heavier weighting on domestic political factors than on the costs of reduced global engagement.

There are also multiple recent examples of China squeezing smaller economies with which it has political disputes by weaponising trade flows, from Norway and Australia to Lithuania, in ways that are not WTO-compliant.

One marker of China’s changed positioning is the difference in international perceptions of China between its hosting of the acclaimed 2008 Olympic Games – in a sense, China’s global coming out party and perhaps the high point of Western hopes for engagement – and its hosting of the upcoming 2022 Winter Olympics, now accompanied by diplomatic boycotts from the US and several others.

The start of (some) decoupling

China’s changing economic and political model, combined with geopolitical rivalry, will lead to some unwinding of economic engagement between China and Western economies (and beyond).

This will be deeply consequential for the global economy: China is the second largest economy in the world, the single largest exporter, a major FDI destination, and has 135 Fortune 500 firms (more than the US).

But although there will be some decoupling, this will be a gradual, bumpy, and costly process. The powerful economic incentives that have driven engagement between China and advanced economies have not disappeared, and these will shape the speed and nature of the decoupling process. Decoupling is a matter of degree, not a binary proposition.

Trade flows to/from China were at record-highs through Covid, partly on a rotation of consumer demand towards goods (see the ‘Chart of the week’ below). Chinese exports and imports were up 32% and 22% respectively in the year to November. This suggests that meaningful trade decoupling with China will take time.

However, the direction of travel is for reduced economic engagement between advanced economies and China. Some supply chains are moving out of China due to higher unit labour costs, even if this is a gradual process. Bilateral trade in sensitive products (such as advanced technologies) will likely reduce more rapidly in response to strategic autonomy concerns on both sides.

And although overall trade decoupling will be gradual, more rapid decoupling is likely in terms of investment flows. Listings of Chinese firms in the US are likely to reduce, due to Chinese pressure as well as enforcement of US regulatory requirements. China has just announced restrictions on foreign investment into technology firms, with similar measures already having been taken in the US. These developments have been negative for the pricing of Chinese technology stocks.

Tougher FDI screening regimes have been implemented in the US, across the EU, and elsewhere, in response to concerns about Chinese investment into technology and other strategic sectors.

As a consequence, there is likely to be fragmentation in the technology space between China and Western economies. Indeed, China is looking to shape technical standards and to strengthen relationships with non-Western countries in order to support the performance of its technology firms (on China’s terms).

Investment into non-sensitive sectors is less impacted, but still more challenging. China is imposing conditions on knowledge transfers, corporate behaviour, and public statements by firms, which will make it increasingly difficult for Western firms to meet consumer, investor, and government preferences in both China and in their home markets.

And the heightened domestic political risk around investing in China in previously non-sensitive sectors (education, ride-sharing) may create concerns about how investable parts of the Chinese economy are. So far, portfolio investment into China remain robust – but there are growing questions about the sustainability of these investment flows.

Although China will remain a key node of the global economy, the intensity of its connections with advanced economies will likely weaken. These dynamics will reshape global economic behaviour and performance: weaker import demand from China, reduced deflationary forces, constrained investment opportunities.

After the transformational impact of China’s rapid integration into the global economy over the past few decades, advanced economies should prepare for more disruption as aspects of this unwind over the next decade and beyond.

To subscribe to David Skilling's email newsletter, use this:

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. This article first ran here and is used with permission. Skilling recently spoke to interest.co.nz in a Zoom interview.

12 Comments

“There are also multiple recent examples of China squeezing smaller economies with which it has political disputes by weaponising trade flows…”

I guess they got that play from the US, which has been weaponing trade, it’s currency, and the international payments system so long the pariahs are clubbing together to decouple themselves from anything under US control.

Seems almost everyone is sick of playing with the others more than they have to.

We are currently seeing cracks appear in chinas RE industry and how this plays out nationally and internationally will be interesting to observe . The BRI will presumably come under pressure also the investing in coal fired power stations has already been withdrawn whether truly for environmental reasons or because it was becoming a stretch. Chinese adventurism in other countries eg. Kiribati, Pakistan etc could do with being curtailed for the sake of peace and this may occur if the domestic economy comes under pressure.

The demographic changes occurring in China, with workforce and population peaking, likely mean the economy doesn't need to be as export orientated any more.

One marker of China’s changed positioning is the difference in international perceptions of China between its hosting of the acclaimed 2008 Olympic Games – in a sense, China’s global coming out party and perhaps the high point of Western hopes for engagement – and its hosting of the upcoming 2022 Winter Olympics, now accompanied by diplomatic boycotts from the US and several others.

The White House apparently sensed that Biden was unlikely to be on Beijing’s guest list. Tass had quoted Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov as saying after a meeting with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi in Dushanbe on September 16 that President Vladimir Putin had accepted “with delight” an invitation to the Games from Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Biden waited for two more months to arrive at the conclusion that he’s not on Xi’s list of invitees. The Olympic rules stipulate that for politicians to attend the Games, they must first be invited by the host country while the International Olympic Committee endorses it.

The Global Times report said that “as the host country, China has no plan to invite politicians who hype the ‘boycott’ of the Beijing Games.” It noted wryly that Biden’s talk of a boycott was “nothing but self-deception.” Link

The Big Panda is big enough to run its own ship. And it has double the market size when you look at the potential of the BRI immediately surrounding them. Then there's Africa up for grabs.

One could argue there's more of a balance to the planet with the unleashing of the 'beast from the east' & we forget very quickly there are more despotic regimes out there then there are good ones - by plenty. Believe me, I've been there. We live in a very insular so-called civilised world of about 1.5 billion people. Most of planet Earth (for the other 6.0 billion) is still a pretty tough place to live. Decoupling won't do any harm. It'll cost a bit more, sure, but we'll control our own IP which is better long term.

Our biggest concern internally is the collapse of our education system to the point where the students are now so far left they will not tolerate learning or hearing anything else. If we cannot teach our own people them we are doomed I'm afraid & until western govts wake up to the woke destruction going on around us & it's anti-everything mandate then within my lifetime (not much of that left to go) China will overtake & control the trade routes that once made us (the West) so envied amongst all the nations.

The noise is about China. But the enemy is within.

Name checks out.

Correct, starts with educating, I mean indoctrinating the young.

This is a deckchair discussion. They are just addressing the sinking in a different manner, as are all nations, more and more. The article correctly identifies that globalism has peaked and that the drift will be to retrenchment behind borders. Then war(s).

Welcome to the Limits to Growth. The trick from here on in, is to keep an eye on the drivers (depletions) and the drivens (political reactions, including blaming as a step towards warring.

Ah well, don't ever say you weren't warned, plenty of us said over and over, when the China appeared to be opening up, pre Xi and early Xi. We warned you all that once China held most of the aces they would start to exert their power in the world. We were called xenophobes, but oh well, I guess it might have made some a few dollars.

Of course, Taiwan's ability to determine its own future is in jeopardy. I guess the west can order in more popcorn.

If China makes a play for Taiwan its going to be all bad. They are one of the worlds largest semiconductor manufacturers and if that stops its going to impact everything. One has to wonder if Taiwan was not doing so well and only had a few sheep instead of their high tech industry, they probably wouldn't bother to invade it.

Adding chips will make the meal more enticing, but even without, it is now a matter of honour for Xi to finish off the Republic of China in Taiwan. But not before the Olympics next year.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.