By Brendon Harre*

I hate the messaging in media reports such as “Will the average house price in Christchurch hit $1m in 2022?”. I believe it is a fecking disaster for the young, the poor, and anyone interested in New Zealand having a productive rather than speculative economy.

The economic effects are massive — everything from cost of living, to staff retention, and the homeless situation.

For those affected, for the young people wanting to understand why they cannot buy or even rent a house, workers interested in retaining their productivity, and society wanting to avoid a further ramping up of poverty and inequality they should make the effort to understand the underlying concepts of who profits from land.

Concepts of interest include fixed versus produced assets, economic rent, natural and extractive land rent, the unearned increment, and socialising versus privatising the gains from land.

Perhaps the best place to start is with unearned increment which is the increase in the value of land that occurs without the expenditure or effort of the landowner. Land being defined as a fixed in nature rather than a produced asset, such as a building. In New Zealand this definition of land corresponds to a properties unimproved rateable value not its improved capital value. The term unearned increment was coined by 19th century philosopher John Stuart Mill, who proposed taxing it so that it could benefit every member of society.

Mill’s concept was refined and developed by the economist Henry George in his book Progress and Poverty (1879). George argued that the value of land increased as population growth expanded the division of labour. George believed that a landowner’s exclusive claim on land granted them the ability to collect increasing productivity as economic rent.

George saw how technological and social advances (including education and public services) increased the value of land (natural resources, urban locations, etc.) and, thus, the amount of wealth that can be demanded by landowners from those who use the land. In other words: the better the public services, the higher the rent is (as more people value that land). Further, there is a tendency for speculators to increase land prices faster than wealth can be produced, resulting in less wealth being left over for labour, which finally leads to the collapse of enterprises at the margin, with a ripple effect that becomes a serious business depression entailing widespread unemployment, foreclosures, etc.

In the later part of the 19th century these concepts had a strong public following. George who did the most to explain these ideas to the public was a rock star economist of his day. His book Progress and Poverty (1879) sold millions of copies and arguably kicked off the progressive era of politics — not just in the US, but world-wide.

From the 1890s a series of transport and construction innovations — including the modern safety bicycle, electrified trains and trams, elevators, steel framing and reinforced concrete, and the internal combustion engine allowed cities to expand exponentially in size — both up and out.

There were also cross city and cross state technological and institutional changes supporting international trade of goods and services, the flow of labour, and investment capital. This includes refrigerated ships, containers, aircraft, long distance rail and highways, telecommunications, trade agreements, floating currencies, less war in places that previously had been ravaged by conflict, such as Europe, and so on. These inter-regional and international factors created a competitive network effect.

All else being equal, cities that were overpriced would lose population and investment growth relative to similar cities and regions that were more cost effective.

During the 20th century competition between expansion opportunities reduced the unearned increment problem meaning the Henry George economic rent concept lost its public following.

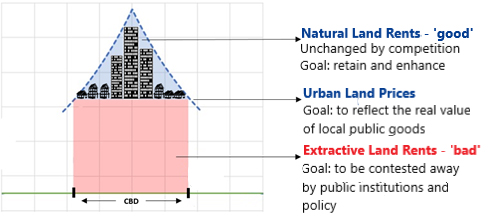

Land rent still existed — what this paper will call natural land rents. Favoured locations because of community growth or access to public services still had higher land values but increasingly in the early and middle parts of the 20th century that land was taxed or socialised in some form or other in a way that facilitated further community growth. The important point was the extractive rent component of land rent — the part that allowed landowners to claim the productivity of others — was contested away.

In more recent decades the political situation has swung away from city building and towards restricting community growth. So much so that the old foe of extractive land rents has returned. Unfortunately, this has not been recognised by many professional bodies as housing writer Phil Hayward notes in his article — Rocket scientists do not forget about gravity so why do planners forget about economic rent?

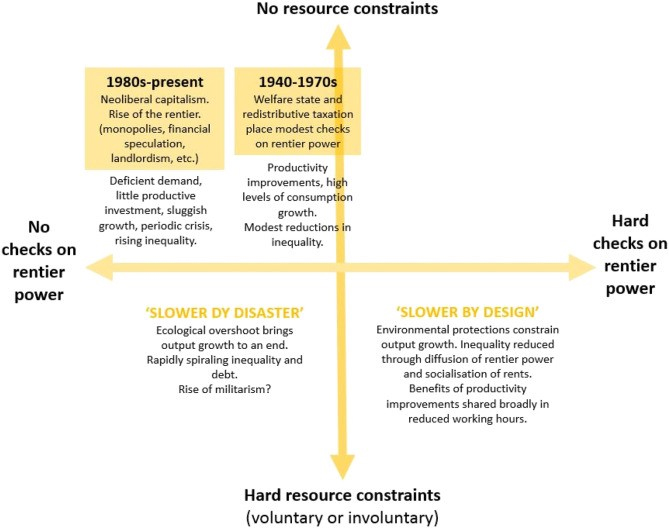

In the 1980s and 90s much of the world, including the Soviet Union and New Zealand, went through a ‘free market’ reform process. The promise of the period — of improving productivity, rising living standards and reducing inequality — has not been fulfilled to the level forecasted. The issue of land rent — the unearned income derived from land ownership and other free gifts of nature — may be a factor in this unfulfilled promise.

For Russia — the major constituent part of the now disbanded Soviet Union — the historic experience since the 1990s has been chaotic oligarchism followed by a re-centralisation of power under a populist, authoritarian and anti-democratic president. The economic advice detailed below about retaining natural land rent for the benefit of society was not implemented.

Over the last thirty years, for much of the world, wealth inequality has risen — most famously reported by Piketty. Yet a more detailed empirical examination of Piketty’s claim that the return on capital has been greater than the rate of economic growth has indicated the problem is not with capitalism in general — but with the excessive rise in house and urban land values.

New Zealand compared to other countries has experienced one of the most dramatic transformations in house prices relative to incomes over this period. Going from a stable median house to income multiple of between three and four for most of last century to over nine in 2021. The on-the-ground reality of New Zealand’s transformed housing environment has been widely recorded by the media — for instance in the podcast — The Impossible Dream of Homeownership.

The country went through substantial economic and political reforms in the 1980s and 90s, yet reforms to the issues pertaining to land rent was not part of that agenda. In fact, the institutional settings required for the acquisition of land to protect future trunk infrastructure corridors and for nation-building public works more generally have been neglected. This meant contestable natural land rents could not be unlocked.

In 1990 an open letter of economic advice was sent to President Gorbachev from a group of independent US and European economists warning of the danger of adopting features of our (Western) economies that constrains prosperity. In particular, the danger in following the West in allowing most of the rent of land to be collected privately.

Ignoring this advice was a missed opportunity — both for New Zealand and Russia.

A key concept in the advice is the natural sources of land rent.

“The rental value of land arises from three sources.

• The first is the inherent natural productivity of land, combined with the fact that land is limited.

• The second source of land value is the growth of communities;

• the third is the provision of public services.” (Note — bullet points added for emphasis)

I would contend the above is true, but the experience of the last 30 years indicates there is a fourth source of extractive land rent, or perhaps better categorised as a subset of the second source — for the situation where community growth is restricted.

Importantly, unlike the first three natural sources of land rent it is possible to contest away extractive rent if public institutions enable it. This has been the underlying focus of many of my previous articles — such as.

- What is the secret to Tokyo’s affordable housing?

- Tokyo does not subsidise its transport system!

- Japanese urbanism and its application to the Anglo-World

- Land Readjustment — Case Study: Kashiwonoha Campus Station

The above suggested approach to contesting away extractive rent has a strong Japanese focus — this is just one of many possible approaches, as the abundant housing series, or my Rack-Rent Housing Crisis series (which has a strong Austrian social housing focus), illustrates.

Restrictive growth can lead to uncompetitive urban land markets that allows private property owners to extract wealth and income from others. The degree that city land supply is fixed or flexible is a key determinant to the degree of extraction, as my paper What is the True Nature of Cities? notes.

This paper does not contend that restrictive land supply is the only factor — a silver bullet — that determines land price inflation. Prices are set by a range of supply and demand factors. For instance, a cogent argument can be made that low interest rates have also fuelled land speculation and asset bubbles. This acknowledgment though shouldn’t undermine the importance of land-use considerations. It is hard to imagine a solution to the housing crisis that doesn’t include the supply of land (up and out) and the building of housing that is affordable for the regular person with a regular job.

For New Zealand policy makers an overarching strategy to city land supply should include socialising the gains from natural land rents to fund the infrastructure required so that community growth is not restricted. The focus being ensuring fiscal incentives are aligned so locational land rents are maximised whilst preventing the growth of extractive land rents. Overall, people should be priced in not out.

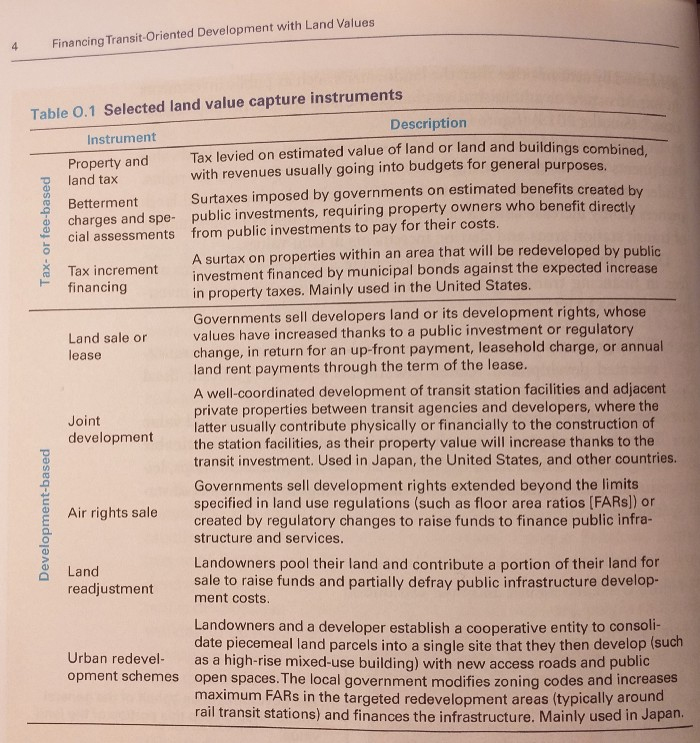

Socialising the gains from land rent to fund infrastructure does not have to be tax- or fee-based, such as, land value taxation or a targeted rate (local government property tax). There are many development-based land value capture tools too — land readjustment for instance, which is well used in Japan, and government land sales which funded some large colonial-era infrastructure projects in New Zealand. Another example is the successful Vienna social housing model which uses an active land bank decades in advance of actual construction. This means todays social houses are priced at yesteryear prices and future social housing will be priced at today’s prices — thus the problem of speculative pricing chasing unearned income is reduced and perhaps eliminated for the most vulnerable communities in the housing market.

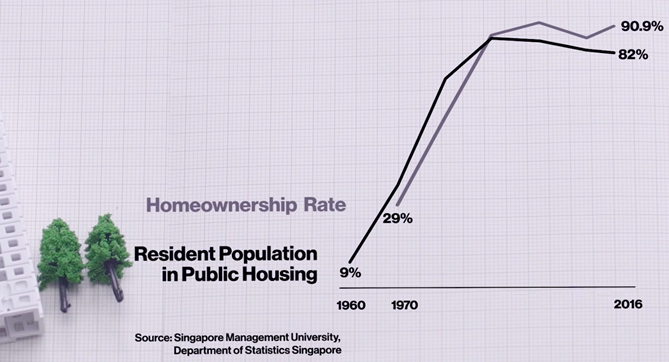

In the first instance, extractive land rent should be contested away. This is certainly possible in New Zealand which has plenty of contestable expansion options — both up and out. Only in situations where community growth is tightly constrained (e.g. Singapore) is there a need to fully socialise extractive land rent by the government owning the vast majority of the land in order to recycle the rent for the public benefit (see the above video link). An Australian economist has suggested for his country a hybrid Singaporean housing model could cut housing costs by 50%.

Governments should to be cautious about removing land price signals. Higher land prices from natural land rent leads to more built floor space being constructed in desirable locations if community growth is unrestricted. Urban planning theorist Alain Bertaud details examples in the Soviet Union and South Africa where governments ignored price signals leading to perversely shaped cities. Others have documented how social housing failed when governments favoured quantity over quality.

For New Zealand though the missed opportunity is allowing private interests to capture land rent pretty much entirely. Moving on from this practice would be a significant mind-shift for the country. Yet it is a strong recommendation of the author that New Zealand further investigates and analyses the issues pertaining to land rent.

Better understanding who profits from land (and other scarce fixed resources) has implications for the resource management system reform programme led by Environment Minister David Parker, local government reform led by Minister Nanaia Mahuta, and how this intersects with infrastructure funding and financing which is led by Finance and Infrastructure Minister Grant Robertson. In the long-term considering how rent extraction might interact with ecological resource constraints may also be important.

Foot Note:

(1) This article provides a useful and well researched perspective but it is important to note it is a UK political party aligned polemic, which the author Beth Stratford acknowledges in her paper. The use of language and the interpretation of history seems to blame the rise of rentier power onto the other side of the political spectrum. Certainly in New Zealand and probably elsewhere too, the re-emergence of extractive land rent and rentier power has been a long-term historic process that has occurred under both left and right leaning governments.

This is a repost of an article here. It is here with permission.

75 Comments

I enjoyed your article Brendon. Unfortunately I doubt we will get any change in strategy in the near-term given the local political climate.

Nothing will change. Turkeys don't vote for Christmas, and these turkeys make the rules.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/300357291/the-houses-of-parli…

The turkeys did change the rules. That is the reason for the building bottlenecks through the 80s 90s noughties. The sixties and seventies had a building boom thus the pollies and beaureaucrats thought that was too many houses. So they dreamt up screeds of regulations and restrictions. But now suddenly they realise what they have done and they start going all out... instantly allowed 3 houses on virtually every lot without RC. And the new legislation implemented in record time.

But where is the tax on the windfall gains that will result?

Will be payable if BLT is triggered. Ird is responsible to make sure

It is easy to get pessimistic about NZ ever resolving the housing crisis. I often am - I have been writing about it for long enough to know that effective solutions are difficult to implement, they involve getting multi factors into alignment, and it is important not to give up or be seduced into one-off silver bullet thinking.

There is some interest in this type of thinking in Wellington. But more pressure is required...

The rhetoric around liberal planning rules allowing 'outward' development is almost always myopic - looking at benefits and not the costs.

The outward ad hoc housing development that occurred throughout Japan, due to some legislative anomalies, may have helped supply of housing but it created a whole lot of negative externalities. Many of these areas were not served by sewer, traffic congestion became a major issue, and they had poor amenity. 'The Making of Urban Japan' by Andre Sorensen is an excellent and authoritative text.

Similarly, sprawl advocates promote Houston's approach but choose to ignore the numerous negative externalities that have come with their approach, including flooding and a huge reliance on the car.

Meanwhile, new towns are brilliant concepts but exceedingly difficult to execute.

Urban redevelopment is the best approach, and if the government lifted their house building programme to massive industrial scale, they could be providing a lot of opportunity for affordable home ownership.

Sadly, this government and it's bloated bureaucracy has neither the appetite or competence to execute such a plan.

All the problems you list result from an increasing population. Knock that on the head and we can turn our efforts to improving our own life rather than improving the life of a property developer or an immigrant escaping their own overpopulation.

Yep agree, although we need to redress existing affordability and homelessness issues.

But yep reduced population growth addresses the issue to a large extent.

Not reduced growth, zero growth.

That’s not a good idea. We have a low population density and a low productivity economy. We need a higher population. The only constraints on the growth of our cities are regulatory ones. Even in Wellington.

NZ would be a far more liveable place with a population of 25m.

A country of 20 Aucklands....that sounds real appealing.

I disagree. As I have seen the population grow over the decades I have seen quality of life decline. I think the two are correlated.

If you think 25m is the right size population just move to Oz...it's waiting there for you. We can then both be happy.

Wow 25 million. You would have to love carbonmonoxide,traffic snarls, and processed food. Give me back 4 million any day

I'm not so sure, a lot of externality mitigation can be funded when competing with sections in the boundary over 900k each.

An interesting article on it from Don Brash the other day: https://www.bassettbrashandhide.com/post/are-we-really-among-the-wealth…

Houston is booming though with a lower house price than the US average its attracting workers and businesses. What's the point in building an Eden that an ordinar Joes can't afford to live in? It's just elitism for urban planning.

Yes it has plenty of economic and social benefits. I don't doubt that, as I alluded to. My point is that it's development model comes with some big environmental costs, which are not mentioned by those who tout its benefits.

I recommend Edward Glaeser's book 'Triumph of the City' on this and many other matters.

Compare California and Texas, which you could both say both have big environmental costs if you are making that environmental comparison, but Texas housing is half the price of California.

For the first time in its history, California lost more people and businesses than it gained, with many moving to Texas.

And Yes, there is probably an irony that Tesla has moved to Texas, to build EVs and the environmental cost that will go with that.

Low Taxes are the reason people and businesses move to Texas, but they end up paying for the lower priced homes and taxes with increased prices and fees elsewhere in the state. We have seen they suffer for the privitisation of everything by no power and water in ice storms, and extreme prices for power and other utilities in the heat when there are artificial shortages of power in the summer.

Following that logic, the higher house prices in California must to linked to the devastating wildfires they are having?

California is facing some of the same issues we do, though, with NIMBYism restraining supply of new housing.

Auckland (for example) can readily sustain masses of more intense building within walkable / scootable distance of train and bus routes. We have plenty of space to intensify, if only authoritarian NIMBYs will stop dictating what others can build on their own land. Shared green spaces and good public transport will be necessary for the future, but we can't do that if we merely sprawl.

It seems to make less sense to keep expanding into prime horticultural land when we know that food security will be a pressing issue in coming decades too, and when doing so requires incredibly expensive (money and environmentally) new roading networks to do so. Rob Adams, City Architect of the City of Melbourne notes that for every 1 million population you can enable to live around the existing infrastructure routes in Melbourne - instead of expanding at the fringe - Melbourne would save an estimated $110 billion. Meaning a saving of $550 billion in accommodating their projected population increase to 2050.

We only need look at the $300k+ per metre some want to spend on putting another road next to the motorway out at Mill Rd...and massive motorway, street, electrical and waters investments needed as we sprawl.

As bad as California is, it is still cheaper on a median income basis.

The point is continually missed by those promoting density only growth. If you ONLY promote up and not out as well, all you do is provide monopoly landbanking which forces up the price of land and housing resulting in families being forced to the city fringe and beyond looking for affordability, ie compact city ideology promotes sprawl.

It has to be both up and out, this will allow housing to be more affordable and allow those that what to be closer in to be able to afford it.

People are conflating density as a proxy for housing affordability. but there is no city in the world where that has happened.

What makes housing affordable is allowing less restrictive land policies so supply can equal demand in developer real-time.

Add in LVT on the unimproved value of land and you don't promote monopoly landbanking, but density.

People are conflating density as a proxy for housing affordability. but there is no city in the world where that has happened.

Is there a city in their world where increased density has resulted in less affordable dwellings available in that dense area than would otherwise have been the case? I don't recall any where allowing more building has made dwellings less affordable.

Growth is easy when you've got heaps of flat valueless land, and very favourable tax positions. Texas knows it's days of cheap oil income are finite, so like many oil states is enticing as much economic activity into the area as possible. The subsequent boom in residential and commercial construction, and influx of new consumers has a considerable element of fiscal velocity. Then growth slows, and public services mount, taxes get raised to pay increasing costs, traffic turns to shit as the population grows, inner city real estate gets expensive.

If flat land was a prerequisite for affordable housing then Aussie should be giving their land away and have supper affordable housing. Brendon is talking about extractive value, not the physical component of land.

Closer to home, some types of flat land in Christchurch cost more to remediate after the earthquakes than their market value or were highly costly to bring to the market in the first place because of the initial poor ground conditions eg previously drained swampland.

It's the cost of bringing land to 'build ready' development that dictates the value-added value of the land, eg remediate flat land with poor soil conditions, or earth removal/fill of undulating land to give a buildable platform. Any other cost above this is mainly extractive value due to restrictions on total land supply due to land use policy.

The main reason Texas land is affordable is not that it is flat good buildable land (because most of it is not), but because they have land-use policies that prevent non-value-added rentier extraction to occur, ie no land banking. They do this by having land-use policies that enable developers to supply land at a truly free market speed to meet demand in almost equal real-time.

The result is a stable housing market with very affordable housing.

You can get a section in Aussie for 30 grand, that's pretty affordable.

You can see that happening in CHCH, they abandoned areas too expensive to rectify/make good, and again you get cheap sections and affordable housing.

Texas is at the earlier end of development curve. We're seeing more established cities come to terms with relatively high ongoing costs to maintain and upgrade existing infrastructure, which makes additional expansion difficult - therefore councils seek contribution costs on new land for their entire expenses, thus higher prices and greater barriers for developers to create new sections.

Its rare for any suburban city to avoid this problem as it matures.

What you are describing has nothing to do with how Texas develops land or the example you give comparing one of the Christchurch sections affordability that will need mitigation to get it to build level, to all Texas sections being build-ready at very affordable prices.

Over 1/2 the growth of Houston in the last 40 years has been via MUD's (Municipal Utility Districts) which are privately funded developments including infrastructure. Think of a Body Corporate on a subdivision or town scale.

The owners fund the infrastructure and ongoing operating costs, they are both cheaper to buy and to run than our public council-controlled bodies.

Yeah, so Houston and much of Texas have been engaging in a low regulation, privatised development model for decades. It's great for growth, because there's a lot less barriers to entry. But now various aspects have been underfunded or ignored and there are mounting bills to pay, and worse disasters like power outages and flooding.

You're conflating the MUDs which are private with public entities, ie the private entities are well managed and affordable, here is a classic example https://www.thewoodlands.com/ but the State and Federal have been poorly planned to some degree. IE the problem, just like what is happening in NZ is the increase in public involvement in housing.

No more than approx. 5% of the population should need to be supported by Govt. subsidies ie State housing. Once Govt. have to be involved in middle-income housing you know its ideological overreach, and in NZ's case, it is a policy failure.

And yes it is great for growth. AND non-growth because they can also stop the supply if demand drops, to always have supply equal demand. There is less chance of what is starting to happen in NZ where we have record consents, half-completed large developments, a large increase in people having bought off the plan, just as banks tighten up on lending.

The Texas model is very reactive to economic conditions of supply equalling demand and can provide volume at a variable rate, both an increase and a decrease and this helps prevent a housing price boom in growth economic times and a housing price bust in low growth economic tomes.

Prices there tend to remain more stable, and the stabilities also helps keep prices more affordable.

It's easy to have cheap everything when you use undocumented immigrants at slave labour rates and the minimum wage of $7.25 p/h wherever possible, which would be twice as much in California at $15 an hour, or more in Australia or New Zealand for our minimum wages. Exploitation does pay.

https://theworld.org/stories/2017-03-06/californias-undocumented-worker…

'She said garment workers, who are often paid by the piece, earn an average of $5 to $6 an hour — far below California's $10.50 minimum wage. Factory owners, many of whom are themselves immigrants, get away with it because a large number of workers are undocumented and afraid to speak out.'

Texas housing approx. 3x median income, California approx 7x median income, NZ approx. 10x median income. You are left with more disposable income in Texas than you are in other states, which you can spend on whatever you want.

Let's all move to Texas!!

https://stateimpact.npr.org/texas/2014/04/22/texas-pollution-worsens-as…

https://environmenttexas.org/reports/txe/illegal-air-pollution-texas-20…

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/plastic-nurdle-pollution-in-texas

https://www.texastribune.org/2014/06/19/texas-among-nations-worst-water…

https://www.npr.org/2018/01/18/578865204/more-states-turning-to-toll-ro…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toll_roads_in_Texas

https://www.dallasnews.com/news/politics/2020/01/09/with-no-state-incom…

https://www.bankrate.com/taxes/state-with-no-income-tax-better-or-worse/

https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/best-states-for-educat…

You are really confusing correlation with causation

You know half the links you have listed, like road tolls, are positives, or fiscally neutral.

And yes Texas has some pollution problems, just like every state does, as does NZ with its very poor infrastructure, Wellington's wastewater, Auckland's drinking and wastewater, and NZ poor river water quality as a few examples.

And at the end of it, Texas house prices are a third of the price of NZ house prices based on median income. NZ houses use to be the same median income.

The question you need to ask yourself is, Why are NZ house prices one of the highest in the developed world compared to our median income, when historically up to 1993, they were one of the most affordable?

It makes me sick hearing left-wing Chardonnay Socialist homeowners pearl-clutch over urban sprawl when house prices are 12x incomes and urban areas only cover 1% of our land area.

It’s not like we need to pave over exceptional landscapes; much of the county is covered in revolting dairy wasteland.

Thoughts on Auckland, though? We have limited good horticultural land in comparison, don't we?

I get sick of Chardonnay Socialists who prevent intensification too, including erstwhile Labour politician turned conservative NIMBY Phil Goff who suggested that Mt Eden is no place for Ockham to be allowed to build affordable apartments.

Must be a place for allowing massive intensification around train and bus routes while ensuring we also plan for future food security.

The outward ad hoc housing development that occurred throughout Japan, due to some legislative anomalies, may have helped supply of housing but it created a whole lot of negative externalities.

Really? From what I have seen in both urban and rural Japan is housing development with rich amenities in terms of infrastructure, which are far superior to what is on offer in NZ and most countries. FYI, I was living there and worked in both the CE and FMCG spaces. I wasn't just visiting so I was living the experience, not just observations.

Curious to know what the negative externalities actually are because everywhere I look in Japan it seems that the place is incredibly well engineered (water systems and public amenities). NZ is not in the same league.

I agree JC. Lots of positive systems. In particular I like the way they fund high amenity greenfield rail projects with land readjustment as a land value capture tool funding 2/3rds of the projects multi-billion dollar rail construction costs. It is genius that NZ if we had the intellectual capacity could copy.

It's an interesting approach with some good outcomes, but again be careful - there's been some failures too!

Japan is NOT an urban development utopia!

But it's a very interesting place to analyse and learn from.

Japan is NOT an urban development utopia!

Do you have an example of anything better?

I don't. Some of that is partially cultural, we number 8 our way through, the Japanese are aiming for precision and being meticulous. It's also a lot more productive when everyone's on roughly the same page, instead of having to cater to the individual.

Hard to say given the different population densities whether we could come close to replicating their approach.

Gee, you are a funny dude sometimes, especially about Japan

What's the problem? I don't get it.

Every place has it's good points and not so good points.

Including Japan. It's not utopia,

Including Japan. It's not utopia

OK, but I think you were suggesting that somehow the weakness of Japan's housing is its integration with public amenities. But that is not the case at all. Its integration with public amenities is incredible. Nothing like it anywhere in the world.

Japan have some fairly large problems, massive public debt, shrinking economy, and underlying xenophobia that makes migration harder.

Still, it's safe, clean, kinda affordable, and the people are obedient and friendly.

I have described some of the problems very briefly above. Of course they aren't universal problems and there's good development too.

Andre Sorensen was a long time resident and academic and expert on urban planning based in Japan and knows his stuff. I have his book which I reference above but it's not cheap or easy to get. He describes in detail the many problems with the ad hoc housing development that occurred on the edges of some cities, in the Peri-Urban locations.

From my own time living in Japan in the mid 90s and having visited many times my view is that much of the housing built up to the mid 1990s is poor in terms of its design, construction quality and amenity but that the quality has improved a lot in the last 20 years. Of course a lot of the older housing is extant, but will he redeveloped in time to presumably much higher standards.

It also depends where you hang out. My family who live in a wealthy suburb of central Nagoya live in a nice (but very cramp) townhouse in a very pleasant neighborhood. But as you will know from your time there an awful lot of urban Japan is very utilitarian and downright ugly.

But great infrastructure, as you say. And great vibrancy.

Actually, many of Sorensen's papers are available online.

As an expert on Japanese cities, he is very balanced in acknowledging both their great attributes and their problems.

This paper outlines some of the problems, with a case study of Urawa City. He builds on this analysis in his book:

https://ur.booksc.eu/book/48186120/3ce944

I have his book too, somewhere. From memory it is about 20 years old so it misses some of the more recent legislative developments that make it easier for Japan to build greater and better urbanism.

I have a book called "Analyzing Land Readjustment - Economics, Law, and Collective Action" which was published in 2007. Andre Sorenson has a chapter in it, too.

The outward ad hoc housing development that occurred throughout Japan, due to some legislative anomalies, may have helped supply of housing but it created a whole lot of negative externalities.

dp

"Sadly, this government and it's bloated bureaucracy has neither the appetite or competence to execute such a plan." So exactly like the previous government then.

What do you mean by industrial scale and how could that be done without enough skilled workforce , materials now. We already have near record high consents , crica. 2,500 state houses built last year. Throwing the kitchen sink at it could cause a bust, especially without a bipartisan population policy.

Good piece. I fear however that the ever present problem of transition (or time) remains....how do we go from where we are to where we need to be without collapsing that which exists in the process?

New Zealand is too insular, too anti-intellectual and too greedy to change.

If not here, where oh Brokkie?

Probably Nordic Europe. Sounds a bit too leftie for you but.

Too accustomed to living it up off debt the next generations are expected to pay.

Jacinda Ardern has finished what John Key started. Feudality has returned, "Sir".

“In the 1960s the planning department of the London County Council, whose unofficial motto was 'Finishing What the Luftwaffe Started,' decided that what London really needed was a series of orbital motorways driven through its heart.”

We could para phase the new Labour Housing Motto as ' Labour - Finishing what National started.'

Ben A's 'Rivers of London' books are a delight....and like Kate Atkinson's, are full of pithy asides about Life......

A few links from under the images are missing - check them out here if you are interested.

See the book — The color of law a forgotten history of how our government segregated America

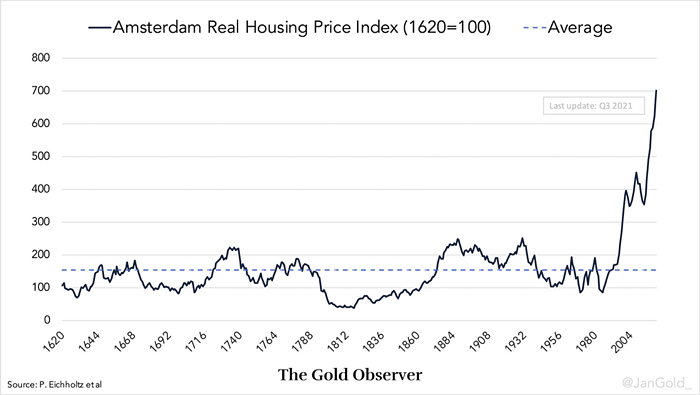

Source — Amsterdam Real Housing Prices Highest in 400 Years. An Analysis of a Bubble

Source: video — How Singapore Fixed its Housing Problem

Source —The Threat of Rent Extraction in a Resource-constrained Future by Beth Stratford in Ecological Economics, Volume 169, March 2020 (1)

How come all so called experts are wise after the event when damage has been done.

Question should have been asked when NZ was burning with housing ponzi.

In my latter years I have come to believe that we never truly "own" land and shouldn't. We do not respect it enough, and believe we have some god given right to alter it forever

A land tax is obviously the one one policy NZ needs. TOP over-complicated it, and Labour ruled it out for seemingly no reason after they got reelected. There’s a Christmas tree farm in the middle of Mt Eden FFS.

Don't Jacindas parents own a farm? They wouldn't approve of a land tax.

We need to address dynasty, monopoly and the unfair monetary system (money creation).

I fully agree. I am bewildered by the massive wealth tumbling down to offspring, tax dodge trusts, property empires extorting unearned cap gains, intergenerational gangsters by any other name

Great article, Brendon. But as ever, the burning question remains: how do we get to the Sunny Uplands of Affordable Housing from here? Here, being defined by:

- A massive housing bubble.

- FHB's left in the gutter.

- Demand for social housing through the roof.

- Gubmint distracted by LG reform, 3 Waters, RMA reform and other top-down initiatives which collectively fail to address any of the drivers of the situation.

- RBNZ conspicuously failing to fulfill their statutory but completely irreconcilable responsibilities for financial stability, housing, employment or even, channeling Michael Reddell, basic research.

- A demonstrable lack of competence in Gubmint delivery of, well, anything really, tax excepted....

- Overlaid with a rising lack of public trust in institutions, 'scientists' who have morphed into minor celebrities, Narratives which are full of logical holes ('vaccines' which don't prevent infection, 'lock downs' which cause mental stress, mandates which cause empty supermarket shelves, and passes which eerily resemble the CCP Social Credit Score system - it is a long list). Trust has to be earned back, and this could take decades.

Given all this, or even some of it where to start?

If you could believe, like they tell us, that the Govt. are in control of things, then we could assume that where we have arrived at is by design, then we could also assume they could enact policy to have a controlled reversal.

The question then also becomes if unaffordable housing is by design, why would they want to reverse a policy they obviously think is good?

Personally, I think they haven't a clue as to what they are doing, hence that is why we are in this mess, and that they have no clue as to how to reverse it in a controlled manner.

I think it will follow the law of universal dualities, Night/Day, Ying/Yang - Boom/BUST.

The only control they have is the public perception of whether the BUST was their doing or by some external event out of their control.

Hence the teams of PR flacks, desperately adding spin upon spin, piling Helion upon Ossa, to keep the Narrative alive. Ardern's major was, after all, Communication......

Political will is a huge issue.

But once the decision is made to act then there are a lot of different approaches to making housing more affordable. For instance - Houston, Tokyo, and Vienna each have more affordable housing than Auckland or Wellington, which they each achieve by very different means. So, this is not a TINA (there is no alternative) situation - there are genuine policy choices.

Waymad as a fellow Cantabrian my recommendation for our region to achieve the sunny upland of reducing extractive land rents and building more affordable housing would be to lean into properly resourcing Christchurch as NZs 2nd city.

I wrote about it here

Sorry Brendon, now in Kaikoura awaiting a consent for a self build of a kitset cottage up here on the Peninsula....Christchurch will just have to soldier on without moi.....

Sounds lovely. Good luck with the project.

Kaikoura, one of the few places in the world where climate change is reversing, notice how the sea level has fallen up to 3 meters in some places ;-)

Fascinating to see the plants march seaward onto the newly exposed land: weeds, ngaios, grasses. Soon there will be humus, then more plants....And out in the briny, the krill, fish, crays, dolphins, paua and seabirds are still there in abundance.

Add to that the rise of anti-intellectualism. Scientists have had to attempt to rise to the task of communicating directly to the public given their advice is so often ignored, yet we've now seen a backlash against science itself.

Certainly started heavily with for-profit propaganda against climate science, but now seems to have flowed through to medicine and more. The amount of absurdity and bizarre anti-science, anti-intellectual stuff spouted on social media has only been growing.

I've even seen people posting anti-science memes that blame science for times companies fought against what the scientific community was saying, to continue selling unsafe products - tobacco, DDT, asbestos etc.

+1 Broadly agree Brendon

1) Very low worldwide interest rates - push asset prices higher (we are in a bubble)

2) Over leveraged mortgage availability for purchasers - 5% deposit minimum (but now raised to 20% for most)

3) Inadequate capital ratios for banks (being somewhat addressed)

4) Non - recourse mortgages unavailable. (Recourse mortgages should be banned) - this would lower the risk of productive business lending relative to housing lending

5) RMA - planners wrote very restrictive landuse rules they dont bear the costs of. Govt changes will help (3 houses + NPS)

6) Taxation - no land tax (re: housing) and no level playing field with comprehensive capital/wealth tax system

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.