By David Skilling*

‘History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes’, Mark Twain

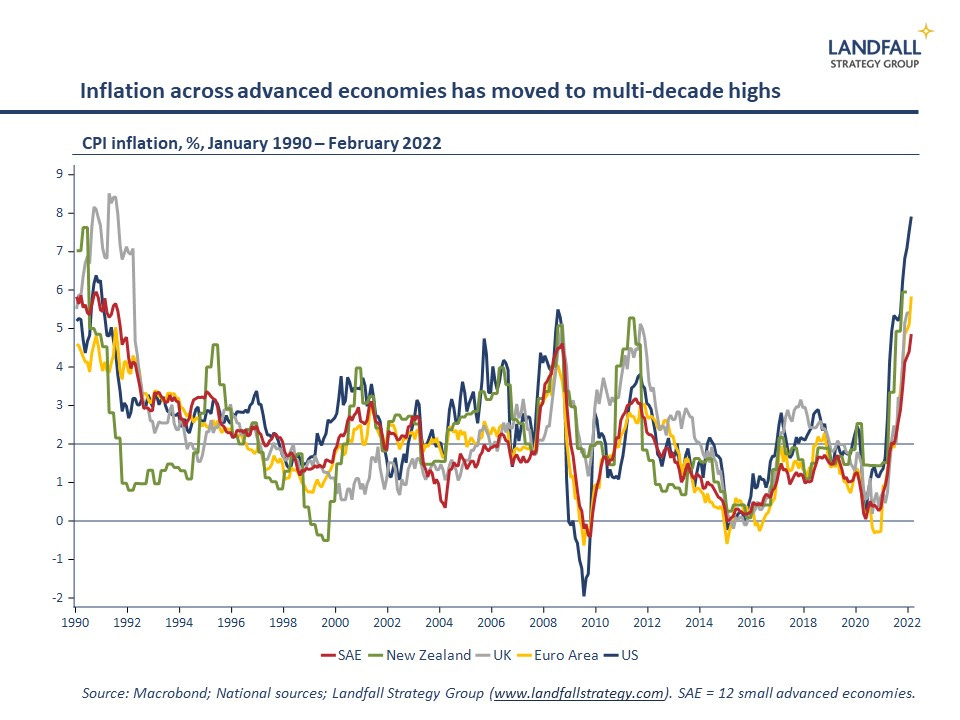

Inflation is at multi-decade highs, energy and commodity prices have moved sharply higher, there is weakening economic activity from Europe to China, as well as geopolitical conflict and tensions, and a fragmenting global economy.

Three decades on from the post-Cold War settlement, the global economy is entering a new regime.

There are parallels to the 1970s. Inflation rose sharply in many advanced economies from the early 1970s, partly in response to expansionary macro policy. And the oil price shocks that came after the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the 1979 Iranian Revolution created price pressures as well as a major economic hit across advanced economies.

International economic and financial turbulence increased after the US unilaterally exited the Bretton Woods system in 1971 and the world moved bumpily to a floating exchange rate system. And the 1970s saw widespread domestic and international political tension and volatility.

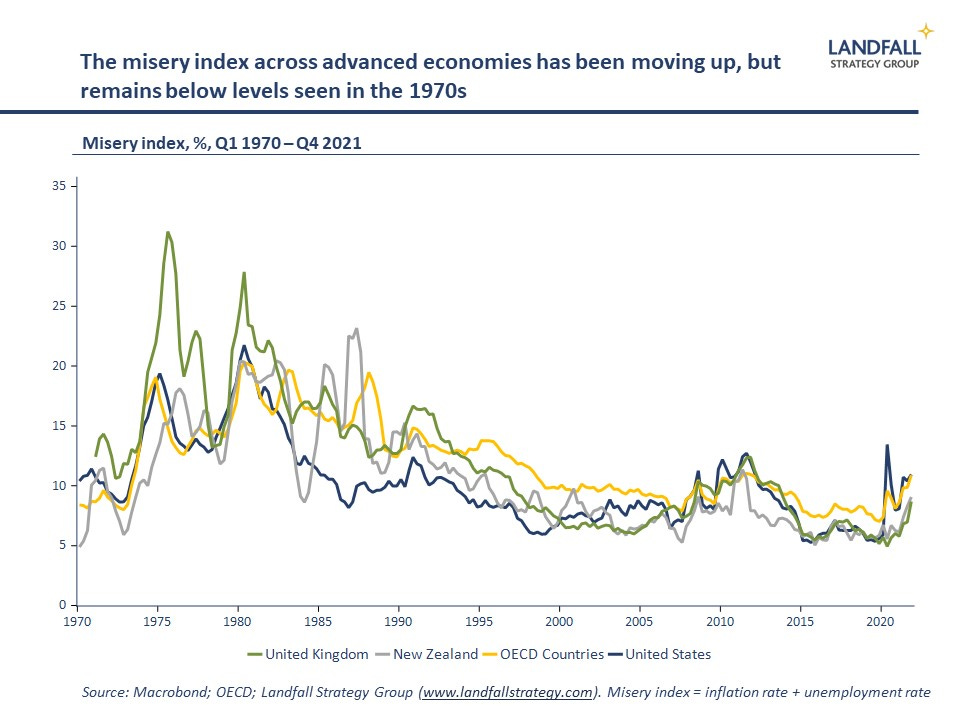

Of course, the analogy is imperfect. Advanced economies are performing better than in the 1970s, with much lower ‘misery index’ scores (inflation rate plus unemployment rate).

Stagflation is a risk, but it is not my baseline: institutions and policies (central banks, wage bargaining practices) have changed across advanced economies, which constrain inflation risks; advanced economies are much less energy intensive; and the underlying economic outlook looks better.

However, the combination of expansionary macro policy (including recent pressures for increased government spending), global supply chain disruptions, decoupling and growing frictions on globalisation (the ‘first world economic war’), as well as higher energy and commodity prices, is likely to create economic conditions that have some similarities to the 1970s.

Economic regime change

But there is a deeper analogy to be drawn to the 1970s beyond higher inflation, energy price shocks, and economic volatility. The 1970s was also a period of economic regime change. The Keynesian economic policy consensus was unravelling, having been pushed to breaking point; the international financial system was changing structurally; and global supply chains were being re-oriented, particularly around energy.

The observed economic shocks, such as stagflation, were largely a function of shifts in this underlying global economic regime.

And so it is now. Consider a few examples. After decades of intense globalisation, a more fragmented global economy is emerging, where global flows are shaped by political forces and where there is a shortening of supply chains. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, together with the accompanying sanctions, has crystallised these changes, and will accelerate a structural reordering of the global economic system.

Covid has also caused major supply-side shocks to the economy, beyond the immediate economic disruption. It accelerated various trends, such as the adoption of new technologies and business models (digital, automation); and seems to have altered labour force participation rates. Covid has also changed the structural growth profile of different sectors, requiring substantial flows of labour and capital across the economy to respond to changing demand.

Energy, industrial, and transport systems are beginning to undergo transformational change to reduce emissions intensity in line with net zero targets as well as changing stakeholder preferences. This will likely be a disruptive process.

And the macro policy consensus has been shifting. There is greater comfort with higher levels of public debt; as well as an emerging tendency towards ‘fiscal dominance’ in which monetary policy is subordinated to fiscal policy.

These significant, intersecting changes that are occurring simultaneously across multiple areas will create new challenges. For example, many of the current inflation pressures are due to the strong global recovery hitting up against various supply-side constraints: global supply chain disruptions; labour supply shortages in high-growth parts of the economy; the rotation of demand towards consumer durables during Covid; as well as higher energy and commodity prices as demand and supply patterns change.

Periods of regime change will likely lead to higher levels of economic volatility, as in the 1970s. At a minimum, we should expect higher inflation than over the past few decades, reconfiguration of global flows, and substantial challenges to labour markets, reinforced by disruptive changes to economic policy across advanced economies.

Policy responses

‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’, George Santayana

The 1970s experience shows that new approaches are required to navigate this world. A key reason for poor outcomes through the 1970s was the policy response, which emphasised demand-side policies and protectionist measures. Policy was designed to offset external shocks rather than to position for a structurally changed world.

New Zealand, for example, responded to the oil price shocks (and the simultaneous loss of preferential access to the UK, its largest export market) with expansionary macro policy and protectionism to support self-sufficiency. Relatively little effort (beyond diversification of export markets) was made to respond to structural changes underway. This did not end well. Massive economic reforms were required from the 1980s to begin to address the problems created.

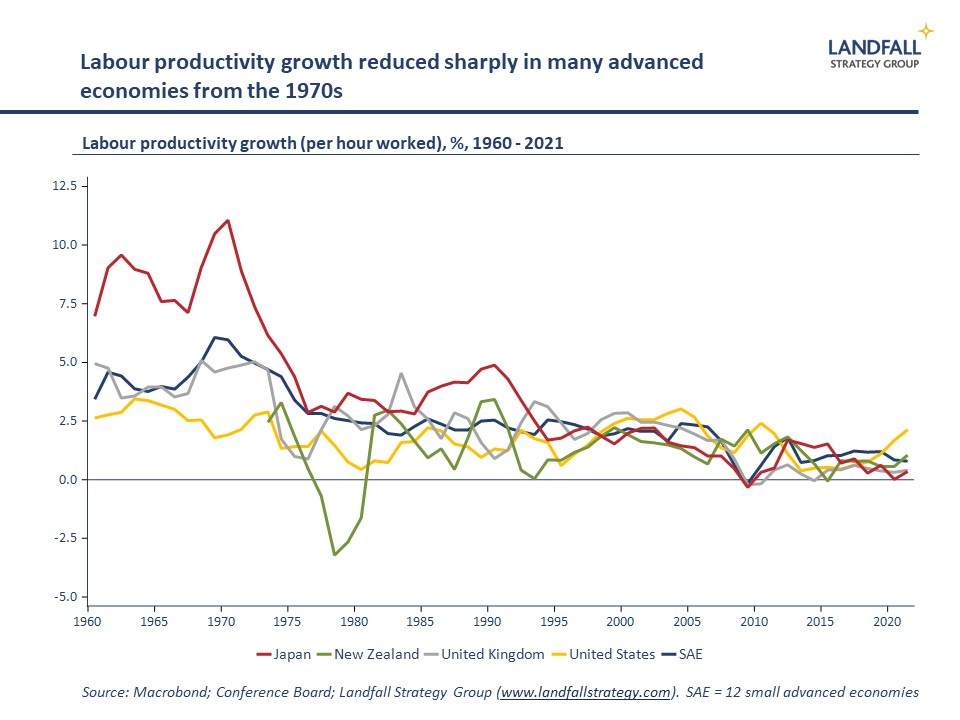

The New Zealand example is perhaps extreme, but it is not unique – directionally similar policies were adopted across many advanced economies. It is instructive that labour productivity growth began to decline across advanced economies from this time.

This experience cautions against over-reliance on macro policy to respond to the current economic challenges. The risk of poor economic outcomes such as stagflation will be higher if governments rely too much on fiscal stimulus to support economic activity (which can create inflationary pressures if bottlenecks in the economy persist); or on increasing interest rates to control inflation that is due to supply-side constraints (which can lead to sharp contractions in economic activity).

The supply-side shocks require supply-side responses, as well as a high pressure economy. For example, governments should be investing to expand productive potential: in renewable energy, to improve the resilience and efficiency of energy systems; in upgrading skills and supporting the movement of labour across the economy, so that people can take advantage of new opportunities; and supporting business investment in new technologies that will enhance labour productivity.

Similarly, the approach to strategic autonomy and supply chain resilience should be based on the disciplined management of exposures rather than de facto protectionism.

The silver lining

Setting government policy and company/investment strategy is difficult in periods of regime change. Deliberate strategic responses are needed to structural change, in the presence of substantial uncertainty.

But despite the many and obvious challenges, there are opportunities as well. There is potential for a post-Covid productivity renaissance in countries and firms that invest heavily in technology and new business models. Indeed, the challenging 1970s saw the birth of companies like Apple and Microsoft – and the development of the successful East Asian growth model.

Countries and firms that adapt most quickly to the new economic regime are likely to perform well. Strategic agility and responsiveness become key assets in periods of disruptive change.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

32 Comments

Draw parallels with the 70s, sure.

Is it the same, no. Internet and media is available, even in orwellian states. Saudis would not have snubbed the US or UK. And China watched the USSR with awe then, now it is the reverse.

China is ascending, building its third aircraft carrier, complete with home made jets. Speaking of peace and trade, every so often.

In our planet, from my eyes, the poorest countries are in Africa and the Indian sub-continent. China has built railways and other infrastructure, but have slowed down, content with natural resources from Africa and new trade routes.

On the finance and economics side, the supply and creation of money, a topic that I know little, morphed into a giant- cannot be easily reversed.

The world population grew, with migration to cities.

And all this while, wars flare up now and then, some larger ones like the world wars and tiny ones.

Homo sapiens, like chimpanzees, go to war.

Some of those poor countries are growing wealthier fast. World Bank annual real GDP growth rate 2013-2018:

6.72% Bangladesh

7.16% India

4.11% Sri Lanka

5.12% Pakistan

compares to 3.25% New Zealand.

the question is : does GDP =wealth?

And GDP per capita?

Breath of fresh air. Countries that agree and deliver the right strategy in the 2020s will enjoy the rest of the century. The right strategy will be focused primarily on securing the real resources that the country needs to live well.

Countries that focus on the money and nudging 'the market' will have a torrid time and will end up just being an increasingly miserable supplier of low value resources to other countries.

Good article. And this very smart man is spot on with this:

or on increasing interest rates to control inflation that is due to supply-side constraints (which can lead to sharp contractions in economic activity).

That's been my central argument as to why the RBNZ shouldn't / won't rise the OCR drastically.

What happens if the supply side constraints aren't resolved in the near term? And we enter a stagflationary recession. Do you leave rates at zero (i.e. the stimulatory setting and ever increasing demand) and hope the supply constraints resolve themselves while inflation continues to rip?

If that scenario plays out, at what point do you say enough is enough and take action (as a central banker)?

Well, if the supply side issues don't resolve, raising interest rates certainly is not going to do anything to help at all.

Interest rates clearly need to rise to take some heat out of the demand side. But as you know, my contention has always been that it won't take much raising of the OCR to decimate the demand side - up to 1.75 would be more than sufficient.

At 1.75, mortgage rates will be starting with a 5. So the cost of debt would have doubled at that point.

Anyway, I know I'm a broken record and in a very small minority!!!

Going to to be an interesting year…either way the central banks have made a real rock/hard place for themselves by electing to kick the can down the road through insane market intervention and pain/recession avoidance 2008-now.

Bond markets are signalling danger ahead with inversions so it is quite possible central banks raise rates into a recession. Could be painful if you have a lot of debt.

H M,

I'm right behind you on this. I think it might get to 2%, but not higher. Why? because by then, the slowdown in consumer activity will be very obvious. Far fewer boats, fancy cars, pools etc will be going on the mortgage even if the banks will allow it.

From a purely selfish viewpoint, with no debt and lot's of cash, it would suit me just fine to see an OCR of over 3%.

Exactly. As Bill Mitchell said so acutely in the NZ context: how will raising the OCR speed up the ships and plug the labour gaps?

It may not speed up the ships, but it does reduce demand for the products on those ships and it frees up labour from marginal businesses.

And that is not to say its all positive but there is a logic to it...sadly a logic thats provided at the expense of those not responsible, yet again.

A competent central banker would be focusing on the quality of credit (who gets it and what for) rather than the interest rate. Slap an extra 200 points on highly leveraged borrowing for residential property by all means, but increasing borrowing costs (input costs) for NZ businesses and expecting prices to reduce is just stupid.

Yes but the horse has already bolted. Our solution to stimulate the economy was the lend more and more money to residential property and that loans were only good while interest rates continued to be lowered to zero.

We should have done what you suggest about 2013 before our bubble exploded beyond what is recoverable without significant pain. Instead it’s been a 10 year property/debt binge…and now we have an external inflation shock, we can’t do anything about it because we don’t control the price if oil or food. Not do we control the Fed whose decisions on interest rate settings and inflation significantly impact foreign exchange markets and as a result inflation experienced by importers and exporters.

Changing the quality of lending now that all of the risk is baked in (ie the debt has been extended to everyone) would likely make no difference at all. In fact it may make it worse…hence why LVRs were removed in 2020 so that banks could lend to almost anyone at all to save the market!

Fair points. I guess the challenge is that no political party has the guts to take action to deflate the housing bubble or take action to kick the speculative investment out of rental housing.

But I thought that is exactly what is happening right now. The bubble is starting to deflate?

A little bit of air is escaping the bubble. My view is that there are too many things propping up the prices for any serious deflation - e.g. hundreds of thousands of equity rich households who will be competing to get into the right suburb as prices drop; serious investors who will buy on the downturn as yields rise; huge injection of govt accommodation supplement to support higher rents (and yields) in less desirable areas; borrowing still cheap etc etc.

sorry pal the numbers don't stack up..yields are too low

and with no increasing values there is no reason to buy

only hot air and hope

we no longer enjoy the job security we had in the 70s,many jobs included housing at cheap rents.so it would be tougher second time around.

advanced economies are much less energy intensive

really?! or have they outsourced some of their energy use? (manufacturing and waste disposal)

ah, it seems he's probably talking about a specific econmic term related to GDP

https://yearbook.enerdata.net/total-energy/world-energy-intensity-gdp-data.html

but surely what really matters is this...?

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-energy-substitution?country=~OWID_WRL

I think this is more a return of the 1940's....we have war time levels of debt...severely negative real rates....and wild swings between avoiding deflation and now inflation.

War time levels of debt? At the end of the last fiscal year, Govt had $285bn of financial assets and $185bn of liabilities (debts). If my maths is right, that's.... errrrm, $100bn in the black?

Look under Govt Financial Statistics here: https://infoshare.stats.govt.nz/

Have a look at US debt to GDP ratios and how that impacts interest rates at different periods including 1930/1940 and comparison to now.

The market has confidence in sovereign Govts with reasonable reputations - the debt to gdp ratio is borderline irrelevant these days. Bond yields reflect the relative desirability of the bond compared to other financial assets. As you said above, this is why the Fed rate matters so much.

$285bn of financial assets

Subject to market forces? Which could drive down the market capitalisation?

Yes, of course.... remember, the value of your investments can go up or down Mr Robertson!

"The supply-side shocks require supply-side responses, as well as a high pressure economy. For example, governments should be investing to expand productive potential: in renewable energy, to improve the resilience and efficiency of energy systems; in upgrading skills and supporting the movement of labour across the economy, so that people can take advantage of new opportunities; and supporting business investment in new technologies that will enhance labour productivity. "

Of course they should! They should have been doing this for the past couple of decades, with the only real major forward thinking infrastructure investments coming from the roll out of fibre. They should be building all the consented wind farms to and looking at making electricity significantly cheaper. High house prices cause employment lock in as well - people virtually unable to upskill or open businesses because they have to keep paying huge rent/mortgages. I have been calling for the mass rollout of the Halter farm management systems as well, a home grown bovine stock management system which could hugely increase farmer productivity - the government could subsidise this to the tune of a few billion per year collar subsidy and reap the benefits of dramatically increased farm productivity. The glacial pace of the studies regarding lowering our farm emissions is also ridiculous, where a billion or so should be put into it a year to transform our climate contributions and potentially create large feed export industries.

There's so much that could be done, if we had forward looking leaders. We don't.

We do have forward looking leaders. They are looking forward to getting re-elected, or elected. Everything else is secondary.....

Buy now, pay later is the best way to beat inflation at a personal level.

The no1 driver for all this is the averageman needs a roof over his head. Rents and prices to the moon from cheap debt and the greed of tax free speculation. DTI will fix this. Why is Orr acting scared now that he has it?

The way banks price loans needs to change from incentivizing residential investors to emphasis on business. If the interest rates were changed to reflect this we might achieve some changes. For example business secured loans cheaper than residential investor loans, family home on lower rate as usual but second home rates dearer than business investment

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.