By David Skilling*

In this week’s global briefing:

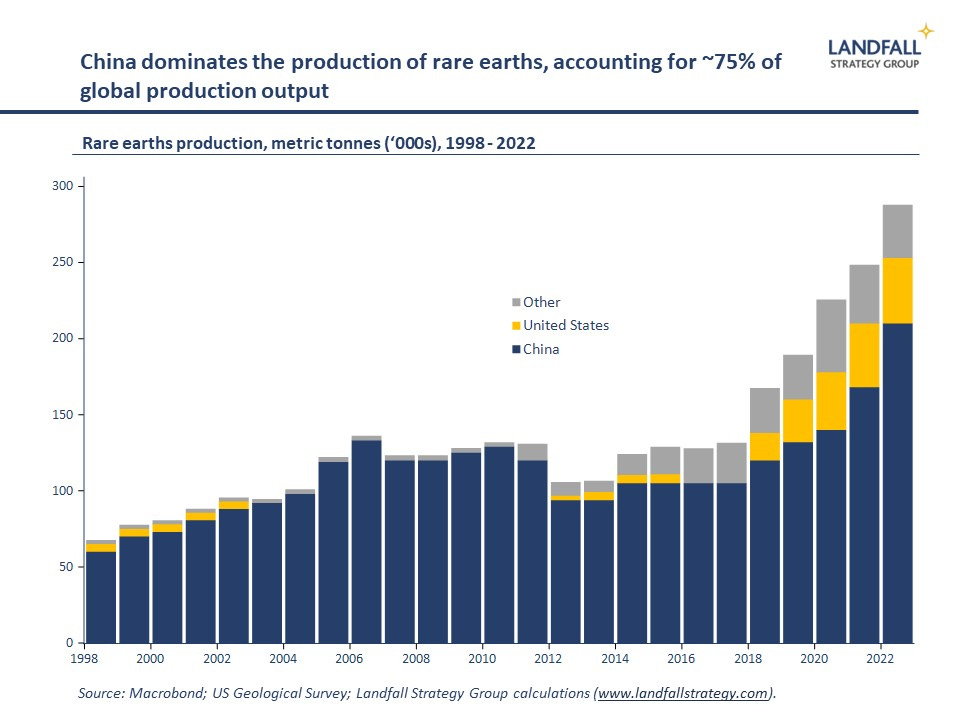

1. China hits back: China’s restrictions on exports of key rare earths are a response to the semiconductor restrictions imposed on it, reflecting some of the leverage that China has. Expect more frictions to come as strategic competition continues.

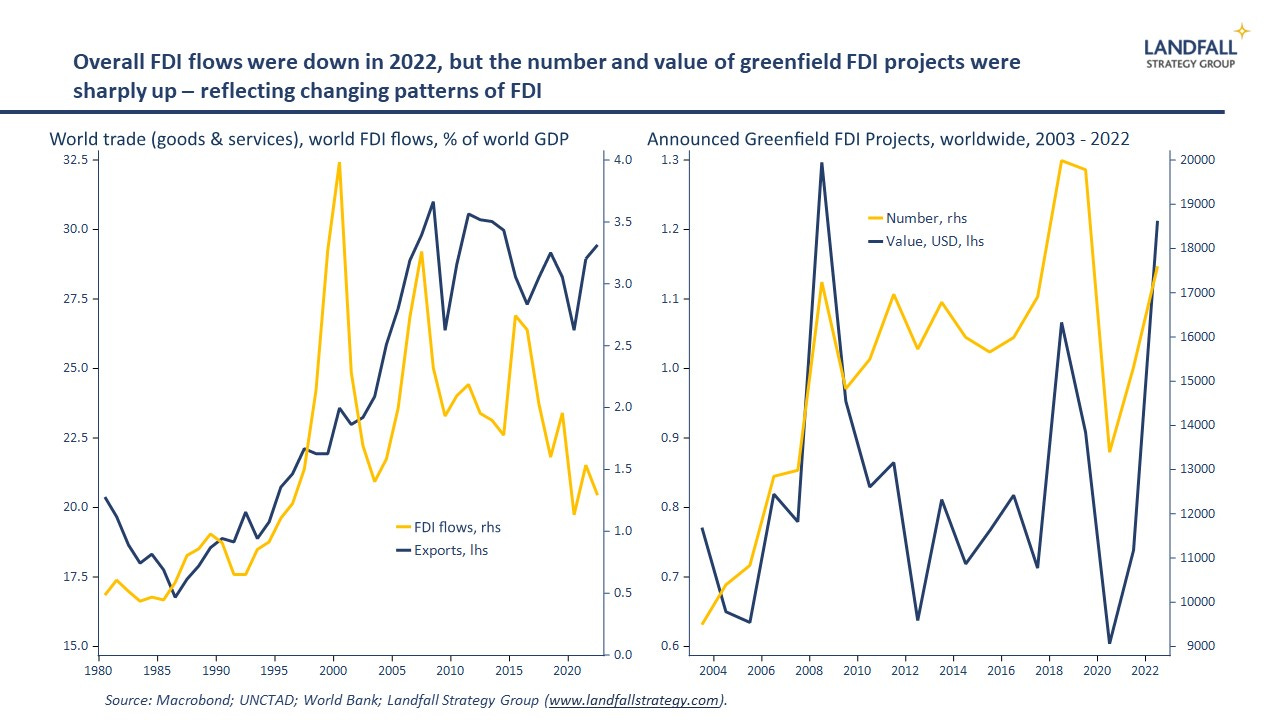

2. Reshaped FDI flows: Headline global FDI flows reduced in 2022, but this conceals an increase in greenfields FDI projects. Geopolitics and competitive industrial policy are reshaping the FDI landscape, leading to increased real economy investment.

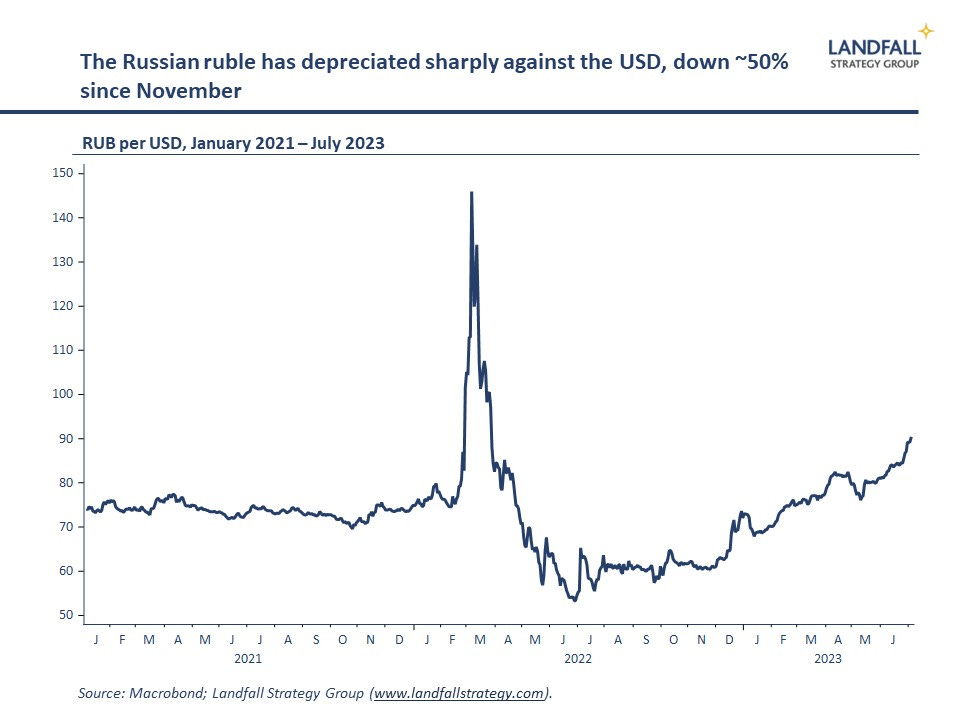

3. Constrained Russia: beyond the short-lived mutiny, Russia faces a series of other constraints. The economic costs of the sanctions are increasingly evident, and it has limited diplomatic support. I’m placing increasing weight on positive scenarios.

4. Disinflation: PPI data from Europe and beyond show the scale of the supply side shocks that are working their way through economies. This sharp unwinding of producer prices will contribute to lower core and headline inflation.

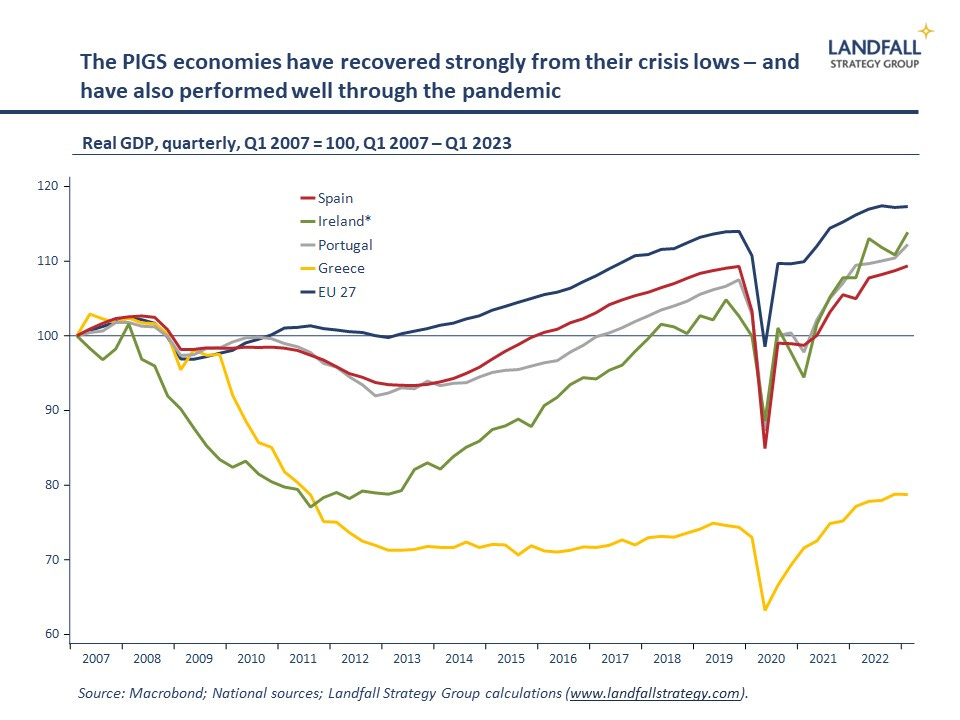

5. PIGS are flying: over a decade on from economic crisis, Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, are growing strongly – largely on the back of good policy choices, which position them relatively well for a more challenging global context ahead.

1. China hits back

Another week, more restrictions on commerce between China and Western economies.

China announced export licences would be required for exports of gallium and germanium from August, rare earths that are used for semiconductor chips, electric vehicles, and other technologies. China is currently dominant in these minerals, as well as in rare earth production more generally; other countries have endowments, but it will take time to build the production capacity to compete.

These moves are at least partly in response to tightening restrictions on China’s access to advanced semiconductors. This week, US plans to impose restriction on Chinese access to US cloud computing services that use advanced AI chips were disclosed. And China’s announcement came just days after the Netherlands announced the details of the export restrictions on advanced semiconductor machinery, which went slightly further than signalled in March.

These Chinese restrictions are a reminder that China has some leverage in this strategic competition, as a result of its sustained investment. The West is currently reliant on rare earths from China, and more broadly for key inputs into the green transition, from solar panels to EV batteries. Firms that are exposed to these inputs are exposed to higher prices and possibly reduced supply.

Indeed, for some time, China has been restricting exports of graphite to Sweden, perhaps to constrain competition from Swedish battery-maker Northvolt, even as it exports graphite to European plants of Chinese firms.

It will take significant time and investment for Western economies to reduce their exposure to China in these areas, although this process is beginning. And these restrictions are likely to accelerate this process of de-risking from China. The challenge for China is that alternative supplies of rare earths can be found; accessing alternative supplies of advanced technologies is much more difficult.

So at the same time, China is also acting deliberately to contain Western de-risking/decoupling initiatives. Last week’s note discussed China’s charm offensive, which has been partly successful (particularly in Germany). On the same theme, in a speech to the SCO leaders’ meeting this week, President Xi said that countries should ‘reject the moves of setting up barriers, decoupling and severing supply chains’.

But the logic of strategic competition is for expanding restrictions with tit for tat behaviour. The ‘small yard, high fence’ approach proposed by Jake Sullivan (discussed here) is likely to lead to a much larger yard over time. The political incentives in the US are for increasingly stringent restrictions; and China is increasingly likely to punch back in key areas: there are many other export categories that China could limit in areas that are of strategic importance to Western economies.

Secretary Yellen, who is on the conciliatory side of the debate, is in Beijing for meetings this week – but expectations are low of meaningful progress. Indeed, last week, China introduced a new Foreign Relations Law, which formally allows for countermeasures to foreign sanctions (effectively codifying the status quo). It also exposes firms that are operating in China to heightened risk of breaching (ambiguously phrased) national security laws.

Implications: Although Western reliance on China for critical inputs means that decoupling is costly, the process of sanction and counter-sanction between the US and China – and to a lesser extent between Europe and China – will likely continue. Exposed firms/economies should prepare for more of this. In a wartime economy, strategic imperatives often outweigh near-term economic costs.

2. Reshaped FDI flows

World FDI flows as a share of GDP have been on a declining trend since their highs in 2000, consistent with the ‘slowbalisation’ story that is seen also in world trade. But neither do FDI flows provide persuasive evidence of deglobalisation: companies and investors continue to deploy substantial capital around the world.

One report that I watch for is UNCTAD’s World Investment Report, providing annual data on FDI flows. The 2023 report with data for 2022 was released on Wednesday. The headline numbers show a reduction in global FDI flows in 2022, down 12% on the year after a big increase in 2021.

This is not entirely surprising: increasing interest rates, the disruptive effects of the war on Ukraine, as well as the expanding impact of investment restrictions arising from strategic competition with China. Indeed, the IMF identified significant impacts on FDI flows already, particularly in sensitive sectors, as global economic fragmentation strengthens. And I have frequently noted that decoupling from China is more evident in investment flows than in trade flows.

However, the FDI data also show interesting dynamics below the surface.

First, reduced FDI flows were largely due to reduced financial transactions by developed country MNCs; for example, reduced M&A activity on the back of higher interest rates. However, there was a substantial increase in the number of greenfields FDI projects (by number of projects and by value). Indeed, in a world of reshoring and competitive industrial policy, FDI will often be a substitute for trade flows. There is more investment in the real economy.

Second, by sector, big investments were made in semiconductors as well as in multiple elements of the green energy value chain (battery plants, and so on). This is partly in response to growing demand (e.g. a need for increased semiconductor production, increased EVs, and so on).

But it also reflects the early stages of competitive industrial policy, as countries like the US encourage massive investment in domestic production (semiconductors, renewables). Indeed, as I’ve described before, factory construction is going through the roof in the US – with substantial investments being made by foreign firms as well as US firms. New investment is needed in sectors where supply chains are being restructured, including for geopolitical reasons.

Third, by country, the biggest number of greenfields FDI projects remains in the US. What was more striking was that China was not in the top 5, either by number of projects or value. Interestingly, India was in the top 5.

Implications: These FDI data are consistent with globalisation being restructured for a world of strategic competition, as well as preparing for the net zero transition. Globalisation is not unwinding, but the nature and location of FDI by firms are changing – driven by geopolitics and policy choices.

3. The walls are closing in on Russia

The most obvious recent challenge to Russia and Mr Putin was the short-lived mutiny by the Wagner forces. This weakened Mr Putin, and has broadened the distribution of possible outcomes (I assess there to be a positive bias to this change, favourable to Ukraine). However, much remains curious: Prigozhin is reportedly still in Russia, not Belarus as had apparently been agreed.

But external constraints are increasingly binding on Russia. On the economic side, pressure is growing as a consequence of the sanctions and other costs of war.

Gas flows to Europe are much reduced, with few alternative markets; and sanctions mean a substantial discount (~30%) between the price for Russian oil and global benchmarks. The attempts to prop up oil prices (with Saudi Arabia) by cutting production are not working well, with oil prices continuing to be under pressure. Russia’s oil and gas revenues are down substantially over the past year, with a rapidly deteriorating current account balance and fiscal position.

The brain drain continues, eroding Russia’s ability to generate income growth. And capital continues to flow out, with offshore Russian deposits increasing. The ruble is at a 15 month low, having lost ~50% of its value since November. Increasingly, there are constraints on the ability to Russia to prosecute the war and maintain some semblance of a functioning society.

The war is taking a massive economic and humanitarian toll on Ukraine as well; but economic and financial support is flowing – with talk of EU accession commencing later this year. This Western support provides breathing space for Ukraine, at least for now.

Things don’t look much better for Russia on the diplomatic side. At this week’s virtual SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) meeting, hosted by India, Mr Putin thanked members for their support during the Wagner mutiny – although it wasn’t obvious what support this was. Nor was it clear what support Russia can get from this group. Although Iran has just joined the SCO, tilting the balance towards autocrats, it does not have a coherent view on the West. Mr Modi is just back from a successful state visit to DC; and there is some discomfort with Russia’s actions.

The friendship without limits with China remains limited. China is not providing material support to Russia, no agreement has been secured to build pipeline infrastructure to China (indeed, China is entering into long-term gas contracts with the US and Gulf countries), and China is concerned about political instability in Russia. I still see potential for China to exert pressure on Mr Putin to move towards a diplomatic resolution.

Implications: Russia has increasingly limited economic and diplomatic options – as well as unclear military options. By itself, this may not change Mr Putin’s incentives. But his hand may be forced. Combined with the recent if short-lived mutiny, there is a case for placing more probability weight on positive scenarios – which would lead to a massive reconstruction process in Ukraine, as well as the relaxation of various frictions on food, fertiliser, and so on.

4. Disinflation

Recent PPI (producer price inflation) data gives a sense of the magnitudes of the supply-side shocks that have hit economies around the world, and which are now working their way through the system.

Europe was hit by supply chain disruptions through the pandemic, and then was deeply exposed to higher energy prices after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. PPI inflation peaked at 43% in the year to August 2022, and has been declining since.

This week’s release of Eurozone industrial producer prices, which captures ‘factory gate’ inflation, showed PPI inflation in the year to May of -1.5% across the eurozone – and down 1.9% on the month. This is driven by a combination of lower prices in the energy sector (down 13.3% on the year) as well as intermediate goods. Further producer price disinflation is expected.

Similar, although more muted, dynamics can be seen in the US and China. In the US, less exposed to higher energy prices, the run-up in PPI inflation was less pronounced (peaking at 12% in the year to March 2022) before declining: it is now sitting at 1%. And China’s PPI inflation was primarily shaped by the disruptions through the pandemic, peaking at 14% in October 2021 – it is now sitting at -5%.

Consistent with this PPI data, CPB report that import and export prices are both contracting worldwide (by around 3-4% in the year to April).

These disinflationary dynamics are partly due to unwinding supply side disruptions as well as by weakening demand in industrial sectors: manufacturing PMIs are in contractionary territory across many advanced economies as well as China.

This is contributing to lower goods inflation, and over time will filter into lower services inflation as well: industrial prices are an input into the cost structures of firms across the economy – including in the services sector.

Implications: Regular readers will know that I think that there are significant transitory elements at work in driving inflation across advanced economies; and that as these supply side shocks work their way through the system, inflation (core as well as headline) will continue to reduce – and perhaps more rapidly than is priced in.

5. PIGS are flying

The newly re-elected Greek PM has been outlining his second-term agenda, building on recent progress. Among other things, ongoing fiscal consolidation with commitments to pay back crisis loans early (Greece is on the cusp of receiving investment grade rating), privatisations of state assets, ongoing economic reform, attracting more FDI, and growing Greece’s export share to 60% of GDP.

Greece continues to grow strongly, on renewed investment as well as buoyant tourism (to which I look forward to contributing over the next couple of weeks). GDP remains well down (~20%) on the inflated levels prior to the global financial crisis, but it is now as high as it has been since 2011. And Greek unemployment is as low as it has been since 2009. Greek equity markets have been on a tear as investors recognise the Greek story.

But this is a broader phenomenon across the PIGS group of formerly troubled economies (defined here as Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain; removing Italy). These economies have staged strong recoveries since their crisis experiences a decade or so ago. Ireland’s GDP contracted by 20%, Greece’s by 30%, and Spain and Portugal had substantial falls – with high unemployment and fiscal problems. But GDP across the PIGS has recovered to pre-GFC levels (except in Greece), even using a more conservative, modified version of GDP for Ireland.

These economies have also had relatively good experiences through the pandemic, particularly in Ireland and Greece. Ireland has benefited from very strong FDI inflows and Greece’s recovery from a deep Covid shock has benefited from a rapid rebound in tourism.

These economies have recovered by following a small economy playbook. There has been a strong focus on fiscal consolidation, supply-side reforms to strengthen the underlying competitive position of their economies, and the pursuit of externally-oriented growth models. Export shares of GDP – a key marker of underlying competitiveness, as well as an engine of productivity growth – has increased very substantially across these economies over the past decade.

In the cases of Portugal and Greece, this has been importantly about tourism. And across all of these economies, inward migration has also played an important role with policies aimed at attracting migrants – sometimes too successfully, which is why various golden visa schemes are being tightened or discontinued.

It also highlights the importance of state capability and political institutions. Greece’s crisis was worse, and its recovery slower to begin, because of policy choices made by the Greek government – the recovery only started with the arrival of a serious, reforming government. In contrast, Ireland responded quickly and aggressively to its crisis and its recovery was super-charged as a consequence.

Implications: These economies have corrected the problems the led to their crisis experiences, and have restructured their growth models more aggressively than many others in Europe. They are well-placed to continue to perform even in a challenging global economic context.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

If you have not already, you can subscribe for free to receive occasional public notes - or take out a paid subscription for full access to these notes:

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

11 Comments

Sorry kids.

"President Biden agrees to send controversial cluster munitions to Ukraine

It's hoped the weapon will boost Ukraine's lagging counteroffensive but the UN says they should never be used - and more than 100 countries have banned them."

https://news.sky.com/story/us-agrees-to-send-controversial-cluster-muni…

3. The walls are closing in on Russia

But what would you expect from Charles Koch and the Cato Institute? Just talking their own book.

If you want to go beyond Wikipedia this is worth a listen.

Charles Koch, the mega-billionaire C.E.O. of Koch Industries and half of the infamous political machine, sees himself as a classical liberal. So why do most Democrats hate him so much? In a rare series of interviews, he explains his political awakening, his management philosophy and why he supports legislation that goes against his self-interest.

https://freakonomics.com/podcast/why-hate-the-koch-brothers-part-1/

or this.

It is disappointing how partisan you are David. MotherJones!? The articles big reveal the Koch brothers gave the NRA $2-3 million to get members voting?! I'm sure you are aware of the hundreds of millions Zuckerberg spends on elections. If you took the time to listen to the podcast you find even people like Obama can give credit where it is due. Life is more nuanced than left billionaires good - right billionaires bad.

Go on David - broaden your horizons and listen to the podcast. It may get the site more subscribers if there is a more non-partisan feed on Interest perhaps?

"We hear praise from some unlikely quarters:

President Barack OBAMA in a clip from the White House: You’ve got the N.A.A.C.P. and the Koch brothers. No, you’ve got to give them credit. You got to call it like you see it. "

Koch Bros? Self entitled rich pr!cks. :-) Why am I not surprised you're a fan?

Oh bless, Palmtree. I love your ignorance. Don't go changing.

"George Soros and Charles Koch don’t agree on much. But they are linking arms to advance a major foreign policy objective they both share: winding down America’s “endless wars.”

https://www.politico.com/news/2019/12/02/george-soros-and-charles-koch-…

On the surface the PIIGS might look OK but, except for Ireland, when you look at ageing populations in Europe they are struggling because birth rates have collapsed and young people left for better jobs.

Spain looks to be doing ok from where I’m sitting

Oh great - Greece is recovering. The only OECD country with a worse balance of payment deficit than us, and they are pulling up. Time to wear the dunce's cap again.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.