We have long been talking to clients about the fact that the way the world operates has fundamentally changed over the last decade. Sally Auld, our colleague and Chief Economist of National Australia Bank recently pulled her thoughts together on this matter. It’s a fantastic summary of all the issues we have been grappling with so we thought we would share it with you.

Key points

- We focus on some longer-term thematics which are important for investors, business owners and consumers. Headlines can be all absorbing, but they often take attention away from significant bigger picture changes.

- Specifically, we focus on the notion of regime change. We are currently in the early years of a new regime which will look and feel very different to that which began in the late 1970s / early 1980s and lasted until circa 2015.

- The new regime will bring with it significant long-term changes for the global economy and financial markets. Lower long-term US GDP growth, a more volatile macro-economic environment and structurally higher inflation are all likely to be characteristics of the new regime.

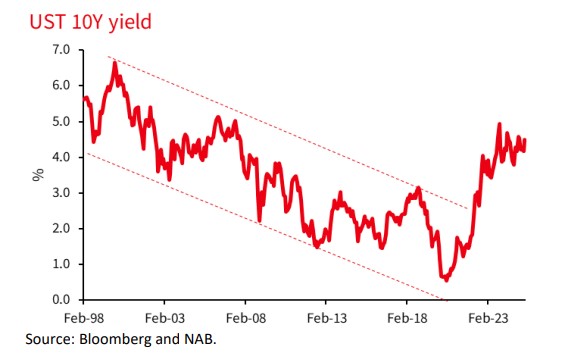

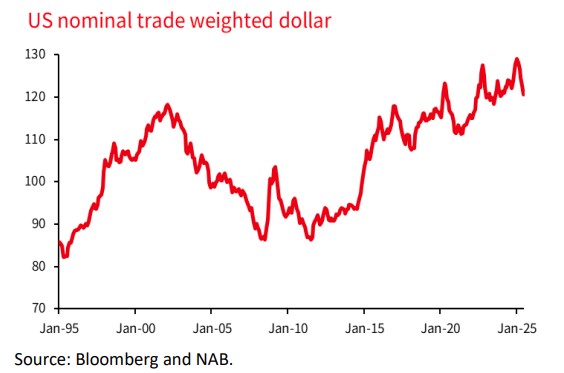

- For financial markets, this translates into a structurally higher and steeper yield curve (think pre-GFC trading ranges), a weaker US dollar and a relatively lower return profile for US vs. non-US equity markets.

- For investors, the new world will demand a different approach to portfolio construction. Some key correlations appear to be shifting, implying that unhedged exposures to US equities are no longer a key source of diversification in portfolios. A new “regime friendly” portfolio might include more inflation protection, more exposure to commodities and energy, and AUD or NZD, less exposure to USD assets, more emerging market exposure, and fewer growth assets.

Thinking longer-term

It can be easy to become distracted by the constant shifts in US trade policy and unexpected geo-political escalations. While these dynamics are important for both anchoring near term forecasts and thinking more broadly about the distribution of risks to those forecasts, they also distract from thinking about some of the longer-term implications of shifts in policy for financial markets and economies. For investors, borrowers and others exposed to financial market volatility, understanding these longer-term trends is critical to gaining a better sense of potential shifts in valuation anchors across rates, FX and other financial variables.

In this note, we take a longer term perspective, first considering the idea of regime change and its utility as a framework for understanding recent developments. We then highlight five longer-term outcomes we think are important and consider the implication of these for financial markets and portfolio construction.

Regime change

The concept of regime change is useful for thinking about longer-term shifts in trends. This framework demands acknowledgment that we have now entered a new, multi-decade economic and political cycle.

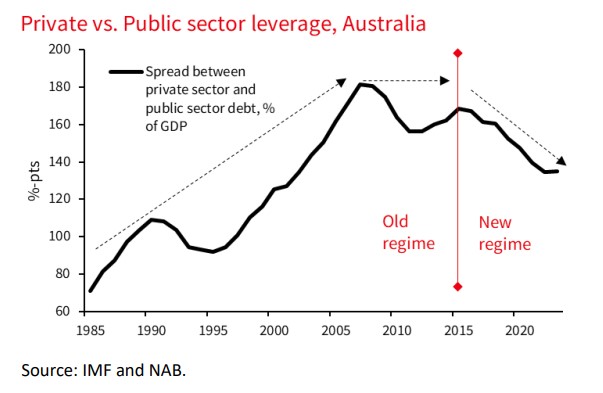

The prior regime was characterised by a commitment to free market policies, and free movement of capital, labour and goods across borders. It was the era of globalisation and the multi-national. In financial markets, it was reflected by a multi-decade secular decline in interest rates, mostly low and stable inflation, and, consequently, a significant valuation boost to real assets (equities, property and infrastructure). It was also an era in which leverage on private sector balance sheets out-paced leverage on public sector balance sheets. The chart below is for Australia but similar conclusions can be reached across the globe.

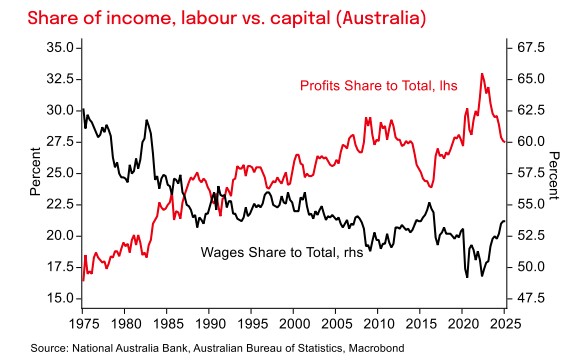

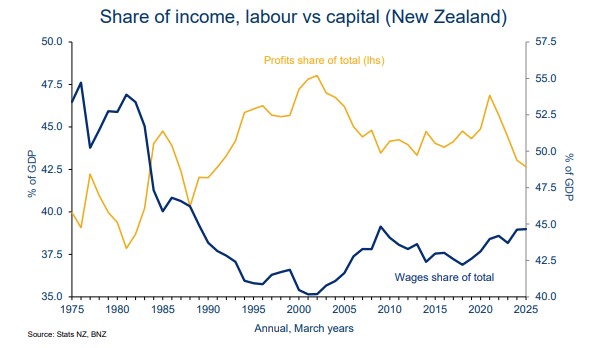

Other features of the old regime were the peace dividend (in a benign world, governments can redirect some portion of defence spending to other priorities), the dominance of liberal democracy in Western economies, and US hegemony. It was also a world in which the gains to capital out-paced gains to labour as surplus was distributed across the inputs to production. We posit that it was this dynamic – inequity in the distribution of the gains of globalisation – which sowed the seeds of regime change. We think we are now moving into an era where the returns to labour may eventually exceed the returns to capital.

The equivalent New Zealand graph is a lot less convincing but we still believe the theme of relative growth in returns to labour will hold. This will be reinforced in New Zealand, and elsewhere, by demographic changes reducing the supply of labour.

In the current regime, which likely began almost a decade ago with Brexit and the first Trump Presidency, the world looks and feels quite different. Many countries are now looking inward, placing national and economic security at the top of their agendas. In the new regime, “old” policies and tools are reimagined – think industrial policy and economic statecraft (tariffs, export controls and sanctions). Supply chain security for critical inputs is paramount.

Economically, the new regime will see less efficient organisation of global production and trade. All else equal, this will come at a cost in the form of lower growth, and most likely, structurally higher inflation pressure. While these forces will work in opposing directions in terms of their influence on long-run nominal yields, we believe there are, on net, other forces pushing equilibrium real rates higher. Indeed, the longer-term influences on the neutral rate of interest is a topic that deserves its own research note.

Against this backdrop, we should expect a higher term structure of interest rates relative to the post GFC trading range (as per the repricing in the chart below) to sustain. This dynamic also aligns with our view of structurally steeper yield curves going forward.

Regime changes are not just reflected in economic shifts, but political shifts too. Indeed, the genesis of regime changes often takes place in politics first, and economics later (think Brexit and the election of Trump 1.0). This is why regimes, as we have described them, tend to be multi-decade events. They are not driven by politics, but rather, political outcomes are the manifestation of slow-moving trends that are the fundamental driver of change.

The big picture

The notion of regime change helps us to put in a bigger context some of the adjustments taking place in the US (and the world) at present across trade, industrial policy and international relations. It should also reinforce the idea that while the temptation might be to think about these changes as only lasting for as long as Trump’s term as President, the broad direction of travel on many fronts is unlikely to reverse once Trump’s term ends.

So, thinking about the long-term implications of some of these changes is important. While the following list isn’t by any means exhaustive, we think it nonetheless highlights some of the more important trends.

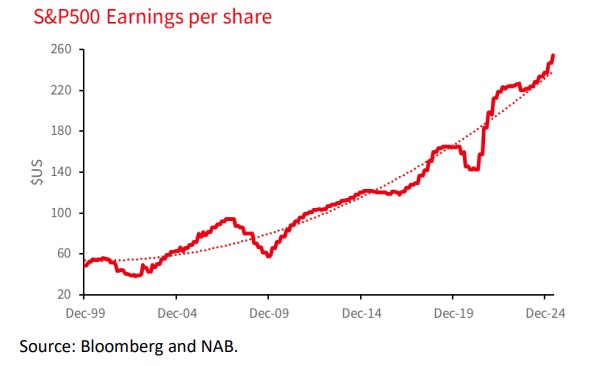

First, tariffs are likely to lower US economic growth (and corporate earnings) in the long run, all else equal. There are a few drivers of this conclusion: first, tariffs will raise the cost of investment, which will lower firms’ demand for investment goods. This lowers the growth potential of the US economy. Second, tariffs also encourage rent seeking behaviour, which forces firms to divert resources away from profit maximization and towards lobbying government. Finally, there is evidence that the most productive and innovative firms in the US are those that are globally connected. Making such interconnection more difficult is likely to come at a cost to the US economy.

Second, inventories will be higher and inventory management more challenging, lifting macro-economic volatility. The desire to secure supply of key commodities, critical inputs into production and consumption goods will mean governments, businesses and households will run higher levels of inventories. In a world of less efficient and possibly disrupted supply chains, the desire to hold inventories will be higher and means that “just in time” inventory management is no longer sufficient.

Running higher inventory levels imposes costs, because in most cases, it needs to be financed or comes at the cost of forgone consumption elsewhere. For businesses, this cost is either passed on to final consumers, or absorbed in margins. For governments, it presents as yet another demand on the public purse. And for households, the opportunity cost of higher inventory carrying costs is foregone consumption.

Regardless, “just in case” inventory management can pose challenges to business profitability and government budgets (too much/too little of the right/wrong good and the right/wrong time). And so it is quite possible that challenges around supply chain disruption and inventory management emerge as a source of macro-economic volatility in both nominal and real variables. While the pandemic experience was quite acute, it nonetheless provides an analogy for thinking about this kind of disruption.

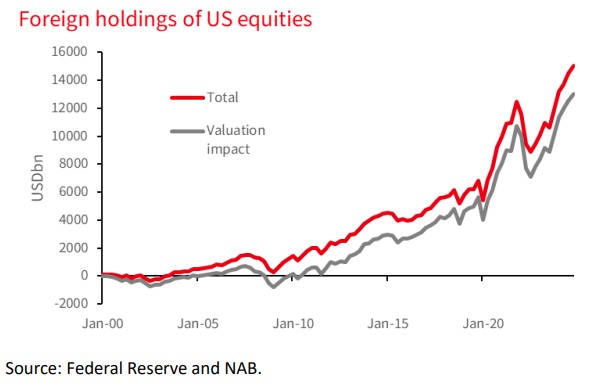

Third, a desire to hold fewer US assets. One of the recent narratives in markets of late has been the “Sell America” theme. We think this is somewhat overstated, given that a relative valuation adjustment (in favour of non-US markets) would go a long way to resolving the extent of (assumed) portfolio overweight in US financial assets. Indeed, if we look at the flow of foreign investment dollars into US equities over the last quarter of a century, we find that most of the increase is in fact due to a revaluation factor, rather than new net buying.

But to the extent that capital inflows have been required to fund the savings/investment imbalance in the US (twin deficits), it is quite possible that a rethink of optimal allocations to USD assets by ex-US investors will require a relative cheapening of both the USD and US financial assets. A shift in hedging behaviour by offshore investors may be enough to generate sustained depreciation in the USD. A de-rating of US equity markets and a repricing of US sovereign bonds may take care of the rest.

We should also note the impact of the shift in US security priorities on the demand for US dollar assets. In the prior regime, many countries were happy to run large reserve allocations to US assets (in the main, US sovereign debt). In the current regime, this may not be such an easily justified decision, because the US security umbrella is no longer providing as much shelter as it once was. Consequently, countries may deploy reserve assets elsewhere or into other financial assets such as gold.

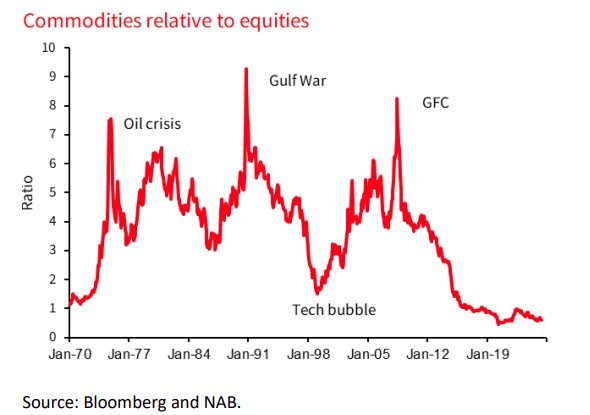

Fourth, and perhaps importantly for Australasia, we think these changes will be supportive for commodity demand and by extension, commodity currencies. While the commodity demand story could be couched as a consequence of broader themes such re-industrialization, re-militarization and reconstruction, there is more to this story.

In a world of more uncertainty – particularly as it pertains to supply chains, national interest, security alliances and energy supply – countries with a natural endowment of commodities (both soft and hard) are likely to be sought after. Shifting global alliances amid renewed national interest priorities are likely to mean less reliance on the US as a global hegemon (and hence less willingness to hold USD assets) and more appetite to look to other nations for mutually beneficial trading relationships.

A final point on commodities – they look relatively cheap as an asset class.

Financial Market Implications

For fixed income markets, we have already noted the prospect of a structurally higher term structure of interest rates, and structurally steeper curves too. We have written previously that this backdrop suggests scope for a structural shift down in the trading range for the AUS-US and NZ-US 10Y bond spreads. While this move might in the near term be driven by changes in interest rate differentials, over the longer term we think it is likely to be driven by compression in the 10Y term premium spread between Australia\NZ and the US.

In credit markets, swap spreads are already very negative in the US. While the US fiscal outlook is in flux at present (with Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” yet to be legislated by Congress), markets are already in the process of rethinking the credit risk of the US government. Against this backdrop, swap spreads are likely to stay negative, and it is possible that some high grade credit spreads trade negative too.

In FX markets, and as noted above, we suspect the main dynamic of the regime change will be a weaker US dollar. This expectation is already embedded in our FX forecasts; we expect a ~12% depreciation in the USD dollar (basis DXY index) in the next 18 months. In trade weighted terms, the chart below highlights the elevated valuation of the US dollar despite a 6.5% depreciation so far this year. Our near-term target for NZD is USD0.65 by year end, with further scope for appreciation likely in 2026.

In equity markets, we think the main challenges are two-pronged; first, the trajectory of profit margins and earnings, and second, elevated valuations. In the prior regime, companies benefitted from cheaper labour (China’s ascension to the WTO in 2001), freer trade, lower company taxes and declining interest rates. It is not difficult to foresee a world where most of these are no longer a tailwind to earnings growth.

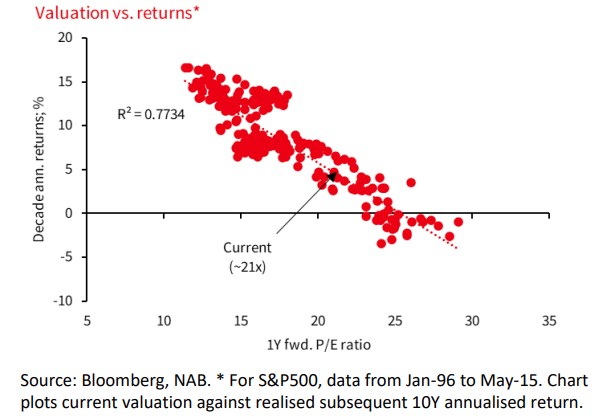

While we have some sympathy for the notion that there has been a structural uplift in the valuation multiple applied to US equity markets, we have more sympathy for the view that long run returns are largely determined by current valuations. A valuation multiple at current levels is historically consistent with an annualized return over the next decade of ~4%.

Portfolio construction

The potential for repeated shocks to supply chains – either because of higher frequency extreme weather events or disruptions to global production – means that investors will likely need to become accustomed to more regular inflationary episodes, short-lived or otherwise.

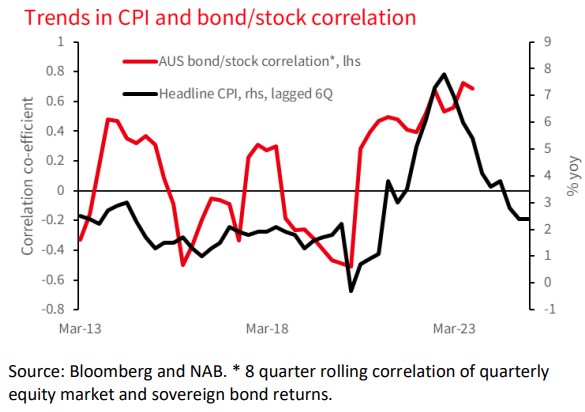

This has implications for portfolio construction, because supply-side inflation often forces a shift towards a more positive (or less negative) correlation between stock and bond returns. For multi-asset portfolios fundamentally premised on a negative correlation between bond and stock returns, this may prove problematic.

We should acknowledge that the low and stable inflation environment of the prior regime (particularly post-GFC) allowed central banks to focus on the labour market aspect of their dual mandates. When demand shocks threatened growth, central banks moved aggressively to protect the downside for fear of inflation falling further below target. Unsurprisingly, stock/bond correlations were quite negative through this period. Most would now happily argue we are no longer in this regime for both central banks and the correlation of asset returns.

While the chart below only reflects the past decade of history, there does nonetheless seem to be some (lagged) relationship between movements in bond/stock correlation and inflation in Australia. It will be interesting to observe whether this persists in the new regime; historically, the chart suggests that the bond/stock correlation should become less positive now that disinflation has taken its course. But the nature of current shocks – geopolitical events, threats to central bank independence and meaningful shifts to trade policy and supply chain security – suggests that asset class correlations will continue to be pushed away from those which persisted in the old regime.

Relative to the prior regime, a new “regime friendly” portfolio might include:

- More inflation protection;

- More exposure to commodities and energy, and AUD and NZD;

- Less exposure to USD assets

- More emerging market exposure; and

- Less growth assets.

Conclusion

There are some significant long-term shifts taking place in economies, politics and financial markets. It is easy to lose sight of these at a time when there is a lot of short-term noise. However, as we have observed, these developments have important implications for financial markets and relative asset price performance. Framing the analysis using the idea of regime change is helpful for providing a context for thinking about such changes. And for anyone with exposures to financial markets, whether they be an investor, borrower, hedger or otherwise, understanding the long-term signal is always more consequential for performance than listening to the short-term noise.

11 Comments

TLDR: MAGA is here to stay according to the BNZ/NAB.

Consequently, countries may deploy reserve assets elsewhere or into other financial assets such as gold.

Hasn't it already been happening?

Gold has overtaken the euro as the world's second-largest strategic reserve asset, according to the ECB's June 2025 report. At the end of 2024, gold accounted for approximately 20% of global official reserves, surpassing the euro’s 16% share.

https://www.wsj.com/finance/commodities-futures/gold-surpasses-euro-as-…

I agree with most of the individual points that the article outlines, but IMO there are some glaring contextual omissions.

#1 THE BRICS ALTERNATIVE - How on earth can this new paradigm be discussed without mentioning the huge multi-trillion dollar BRICS/BRI payment systems, cooperative trade, connectivity, and security projects that are all up and running?

These initiatives already form a multipolar alternative to the status quo US-based financial system - one which chose to weaponise the privileged position that had allowed it to live far beyond its means for decades.

#2 FIAT - A BROKEN EXPERIMENT - Surely it is high time we accepted that the fiat system is broken beyond repair and that the 54-year casino experiment is about to be replaced with a sound money system

We also need to understand why this change needs to happen - and ask the question as to why there is barely a single sustainable egalitarian fiat currency economy out of the ~190 countries on the planet.

China and Russia, both of which deploy a public utility banking model have worked, even in some of the most challenging circumstances - but even they are in the process of throwing out the fiat system.

In fact, on June 26, China quietly announced that they are gold-backing their yuan.

The Bank for International Settlements told us back on Jan 1 2023, that they were preparing to throw ALL fiat currencies under the bus when they designated allocated gold an NSFR Tier 1 balance sheet asset.

Then came the revelation, that based on 2023 numbers, the US true Productive GDP is only one-third of China's, and that now in 2025, India too has surpassed the PGDP of the US, relegating it to position #3.

China's recent announcement is the first major consequence, in terms of a major country reacting by hard-backing its currency.

Now that China has taken its first step - expect other BRICS countries to follow suit, and a brand new reserve asset architecture to evolve for the entire global financial system.

Because of the need to avoid the Triffin Paradox, I would expect that China will be very supportive of other BRICS countries following their lead, and moving to hard-back their currencies too.

This will mean that within the BRICS bloc, countries will be comfortable with holding a variety of hard-backed currencies as reserves, and this too will soften the Triffin effect on the exchange rate effects on reserve currencies when they become too dominant.

#3 SOVEREIGN BONDS - As I see it, the huge global sovereign bond market, which is far bigger than all of the stock markets combined, will have to be completely re-invented, once these currencies that carry negligible currency shift and counterparty risks, enter the limelight.

Countries will subsequently have a wide array of choices in their reserve asset portfolios, including the most obvious ones...

(i) Physical allocated gold - already an NSFR Tier 1 balance sheet asset.

(ii) Other precious and semi-precious metals, including silver, which could become monetized in the very near future.

(iii) Many durable commodities (that carry no counterparty risk) that can be held in reserves for future use.

(iv) Any other hard-backed currencies of other countries, especially those that they already trade with.

(v) Fiat-based US dollars and treasuries, and those of other countries, that have considerable counterparty risk - particularly those that can be weaponised/seized/stolen/etc, at the drop of a hat.

I find it very curious that none of these monumental impending changes in the entire global financial architecture were mentioned in this discussion.

This seems to be the standard reaction regarding all things BRICS, amongst the banking establishment.

IOWs, act as if this juggernaut doesn't exist and hope it disappears quietly into the night - a foolhardy 'strategy' if you ask me - especially in NZ's case, where we have done a big fat zero to get our house organised in time for these massive changes.

Cheers

Col

Physical allocated gold - already an NSFR Tier 1 balance sheet asset.

Gold is recognized as a Tier 1 balance sheet asset for capital adequacy purposes under Basel III, but it is not treated as a Tier 1 asset for liquidity purposes under the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR).

Yes, this liquidity issue is certainly a hot topic for debate, Phoenix.

I assume you are referring to the High-Quality Liquid Asset (HQLA) definition for the Liquidity Coverage Ratio.

Many experts disagree that HQLA Tier 1 assets are limited to cash, central bank reserves, and certain high-quality government securities.

It might also be a jurisdictional issue too - especially in countries like China and India. I'm not saying you are wrong - I need to research this subject more.

Cheers

Col

Here's a clarification from LBMA.

Tier 1 refers to capital rules that were written in the original Basel Accord in July 1988 which became known as Basel 1. HQLA is a function within the liquidity rules of LCR and NSFR which were first written into Basel 3 and implemented by Basel on January 1, 2019. People are getting mixed up between capital rules and liquidity rules. LBMA is advocating for gold to be reclassified as Level 1 HQLA – again note this isn’t Tier 1 because HQLA relates to a liquidity rule.

https://www.lbma.org.uk/articles/gold-and-hqla-correcting-misleading-on…

as people extract savings to buy gold (unless paper via banks) it is INCREDIBLY DEFLATIONARY to banks, they are lending at 20-30-40 times your savings.... if you take $5800 out to buy an one ounce ... and 1 million did this

DO THE MATH

Who are you buying the gold from and where does the money you give them end up?

There is also the wealth sentiment that can come into play, IT.

When gold prices rise, as opposed to paper wealth that is always quietly eroding, physical gold holders tend to feel wealthier, and may spend more, offsetting some of the potential deflationary demand for goods and services.

Some individuals may choose to store a moderate amount of physical gold in a new concept like Kinesis, where you store some of your wealth as allocated gold collateral, and you get a monthly yield on your holding rather than a bill for storage.

Kinesis is already up and running in NZ and is compatible with the NZ dollar.

This system allows you to send money to many global jurisdictions within seconds for negligible charges. It is a cooperatively owned payment system that relies on billions of daily transactions at minuscule charges to make the system work. There are no third-party rent seekers or profit clipping the ticket.

This is the beauty of the sound money renaissance that we are witnessing around the world as the casino fiat systems self-destruct. There are many ways that the commercial banking cartels can be dis-enfranchised, money velocity and liquidity enhanced, and the silent wealth thief (inflation) tackled.

Advances in technology and the efficiency with which goods and services can be supplied, in a sound money system, mean that the natural state of the economy can be deflationary - this encourages a savings culture, and those savings can then generate a real yield for depositors.

Liquidity for the economy and loans can flow from old-fashioned fractional reserve lending on this collateral, rather than as in the status quo, where a cartel of private bankers creates ~98% of MS out of thin air when they write up loans.

A constructive & thought provoking article, thanks

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.