By David Skilling*

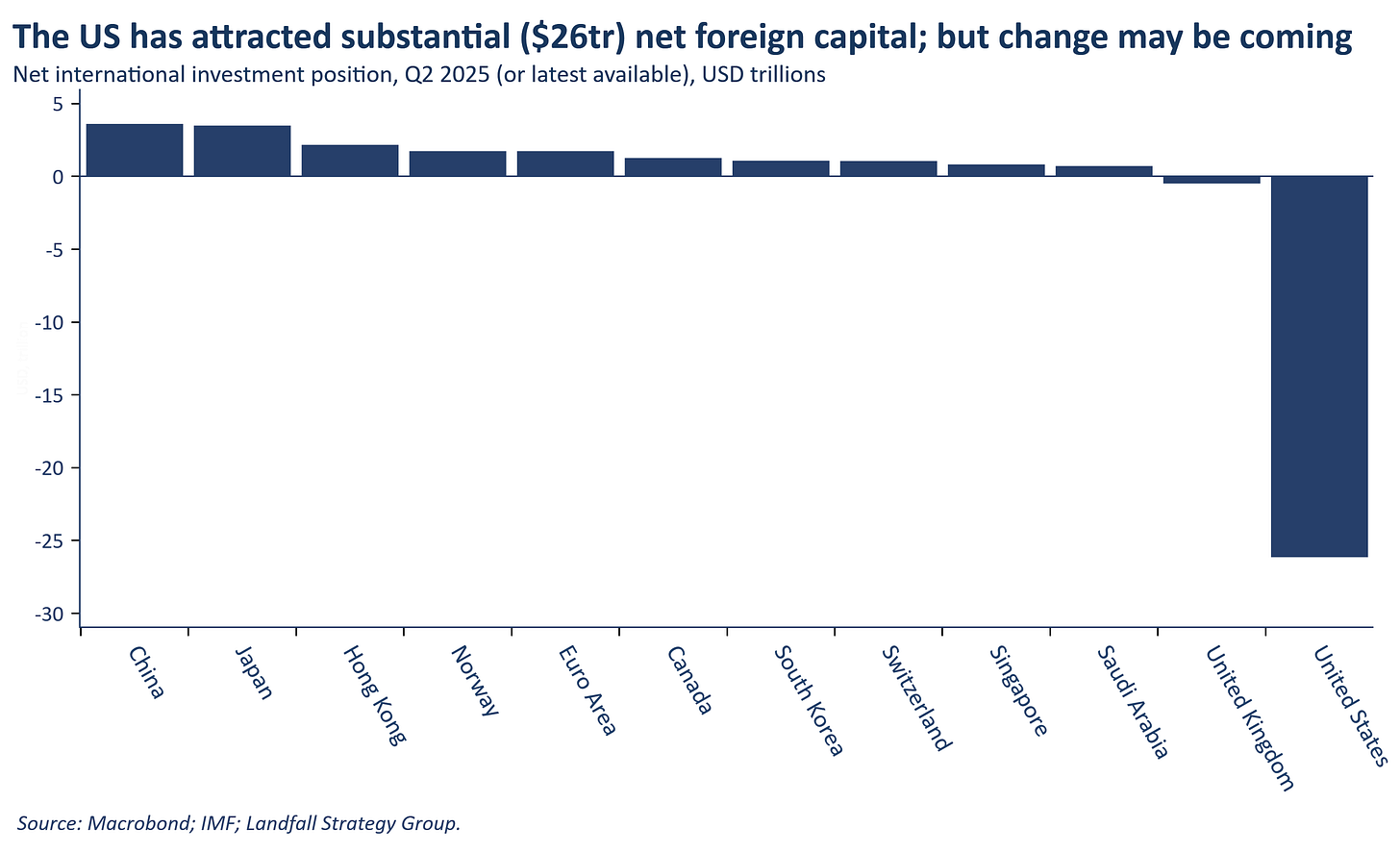

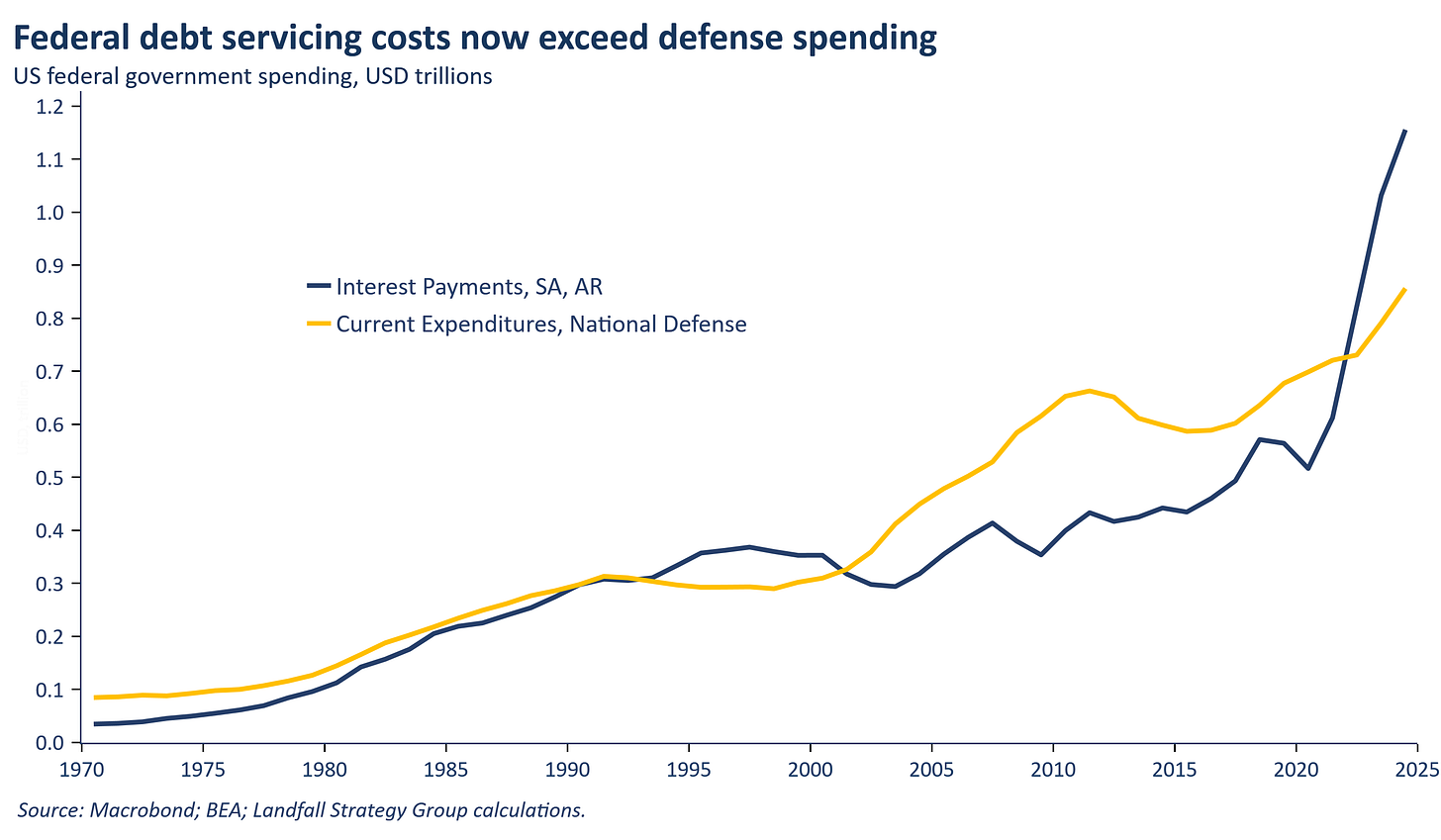

For more evidence of regime change in the US, note the recent striking split-screen of an unprecedented gathering of US military leadership from around the world at the same time as the US federal government was pushed towards shutdown. Despite ongoing strong US economic performance and technology leadership, the combination of changed US economic/fiscal and geopolitical dynamics will challenge the previously unquestioned ability of the US to attract substantial allocations of capital from the rest of the world.

This is just one reason to expect disruptive changes in the profile of global capital demand and supply flows over the coming years, and accompanying policy responses, with potentially seismic economic and financial effects. This note discusses seven recent developments that provide insight into some aspects of these changed capital flows. [And see a recent note for some additional context on the coming capital wars].

1. This time is different

Government shutdowns are unfortunately no longer unusual in the US; and most pass without first-order economic or market consequences. But this episode may be more consequential. For one thing, it may be more prolonged: Mr Trump is not negotiating like previous Presidents, and the shutdown allows the Administration to pursue the Project 2025 minimal state agenda. But even if there is a quick resolution, this shutdown has already reinforced the sense of accumulating political risk in the US. Combined with other developments (such as Liberation Day), this shutdown is a negative signal about institutional stability and effective governance in the US. It is also a reminder of the worsening US fiscal situation.

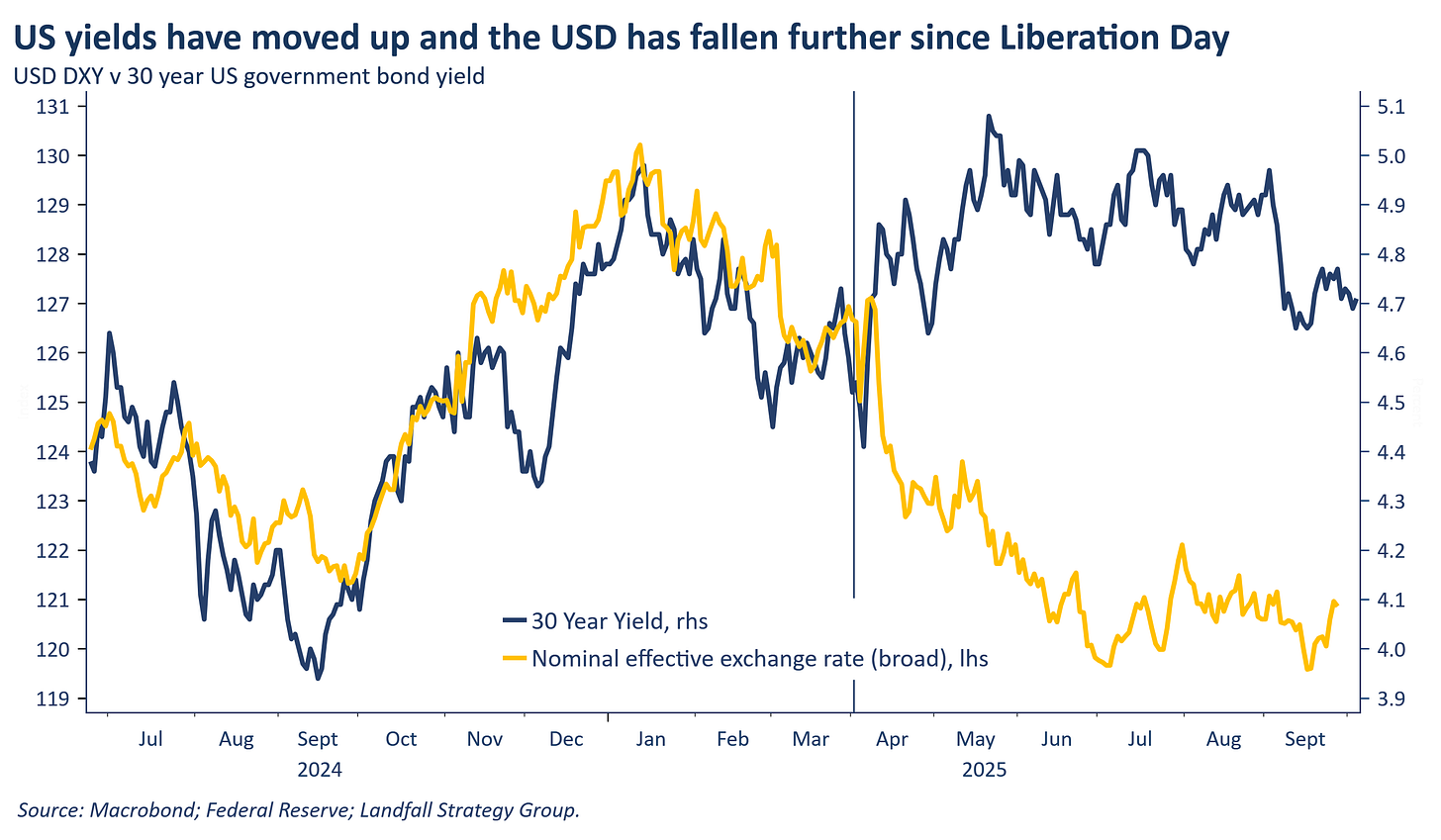

The US will need to attract substantial amounts of foreign capital to fund its widening fiscal deficit, as well as productive investment in AI, energy, and more. This is not a great time to be reducing the attractiveness of the US as a destination for capital. There is little evidence yet of an at-scale reallocation of capital away from the US in response to these political and geopolitical risks, and US equities continue to attract foreign inflows. But USD exposure is increasingly hedged by investors, the USD remains under pressure, and US 30-year rates been elevated through 2025. Political risk will increasingly weigh on capital allocation choices.

2. Safe haven?

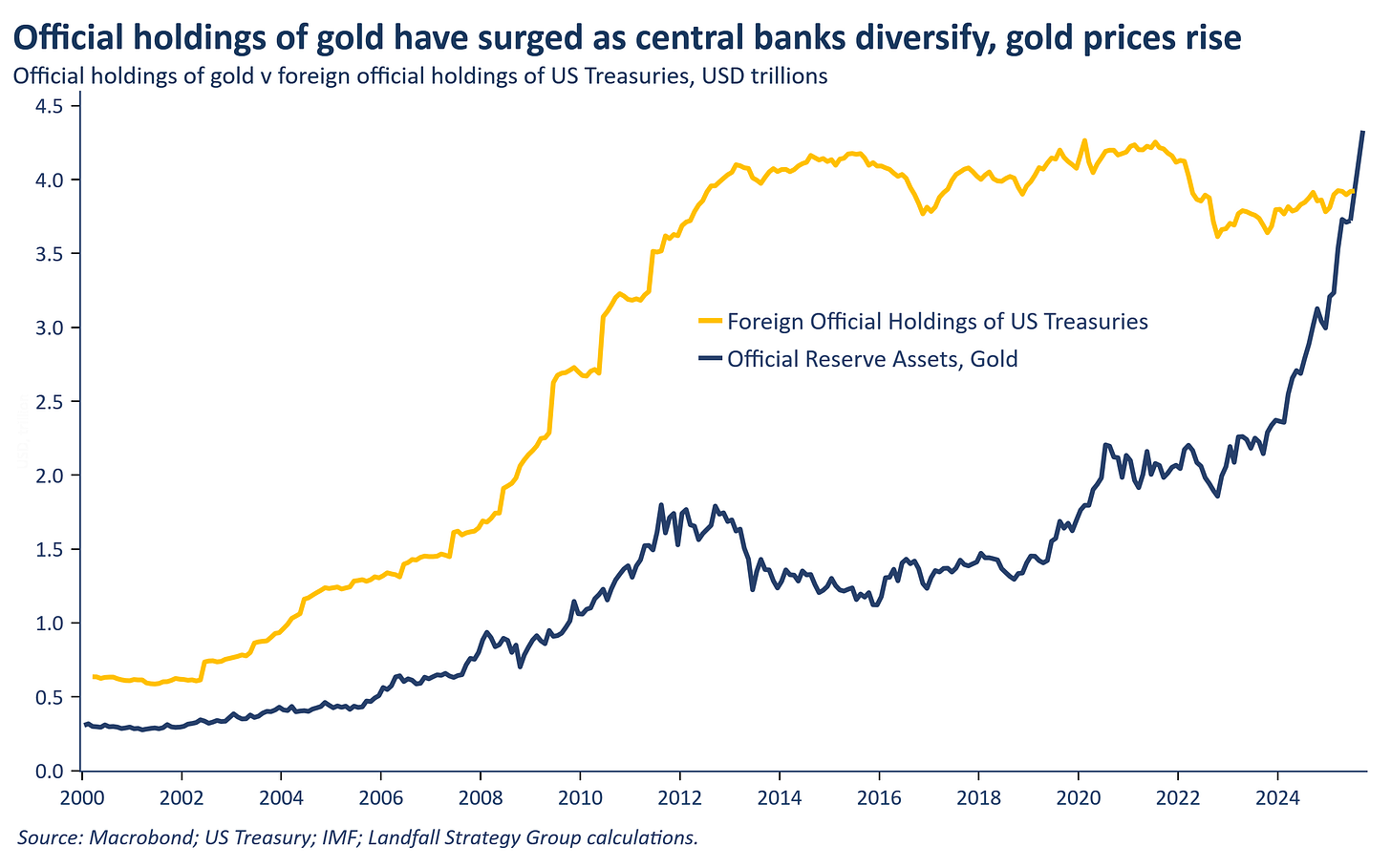

Indeed, there is a slow motion move by foreign investors away from US Treasuries: the share of Treasuries held by foreign investors, including official holdings by institutions such as central banks, has reduced from 49% in 2013 to 31% currently. As another marker of change, the value of gold held in official reserves worldwide has just overtaken foreign official holdings of US Treasuries. This reflects sustained central bank purchases of gold over the past few years (notably China), partly on diversification motives, as well as the surging gold price (up 40% in USD terms in 2025). Private and public investors are looking for alternative safe havens, given the increasing assessed risk of US Treasuries. And in addition to China’s gold purchases, China also seems to be investing its reserves in various commodities.

3. USD centrality

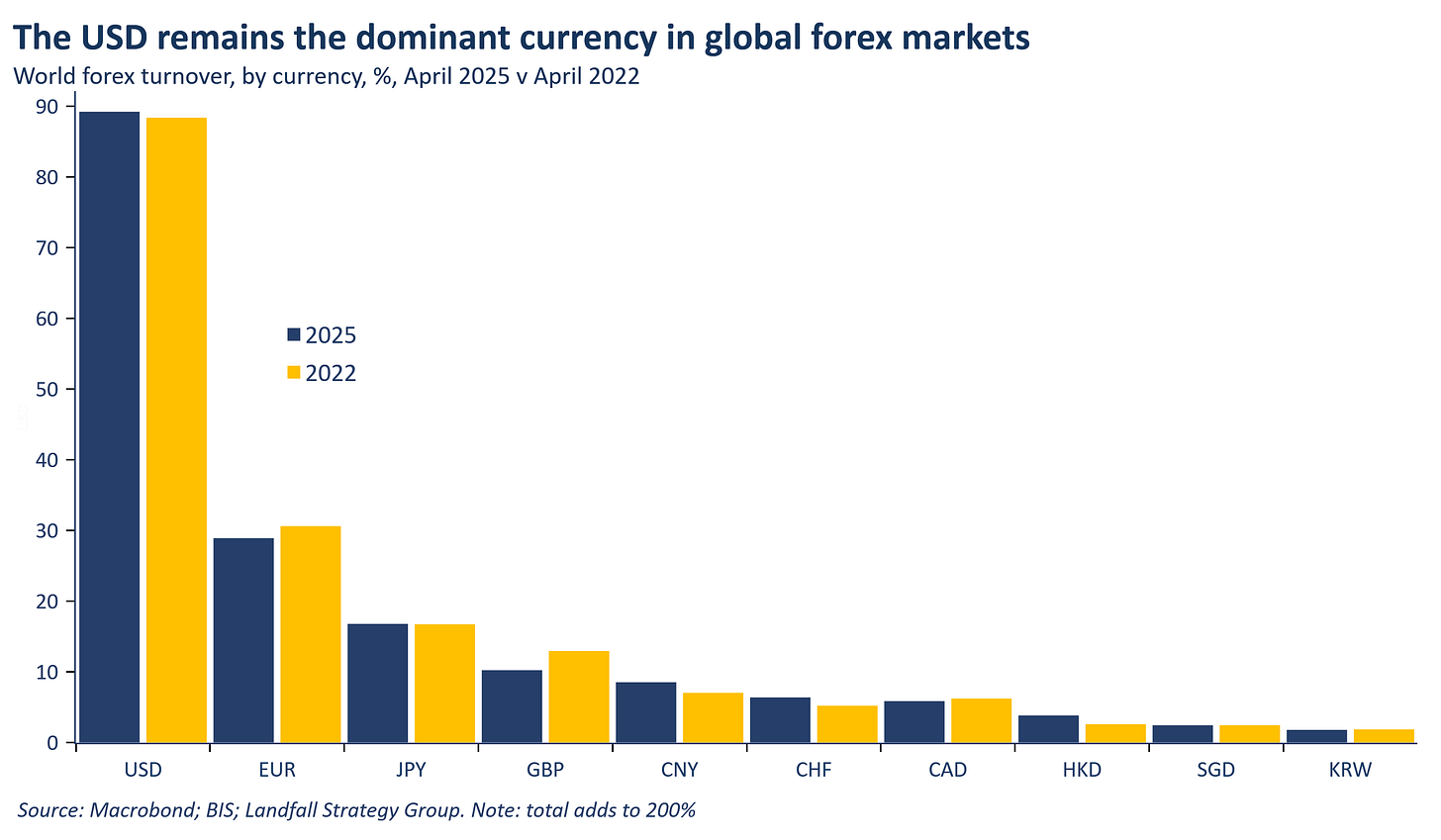

Of course, the USD remains central in central bank reserves (56% share in Q2) and in global payments. The triennial BIS survey of forex turnover was released last week, which showed that the USD remains in a dominant position: the USD is on one side of 89% of global forex transactions in April 2025, up slightly from April 2022. The euro remains a distant second (29%), the yen has a 17% share, with the CHF climbing slightly on safe haven flows. The CNY continued to strengthen to an 8.5% share, nearing the GBP in 4th; separate data shows that over half of cross-border transactions in China are now transacted in CNY. This survey also shows that Singapore continues to close in on New York as the second largest forex trading hub (behind London), one marker of a move to a more multipolar economic system.

4. Fed independence and fiscal dominance

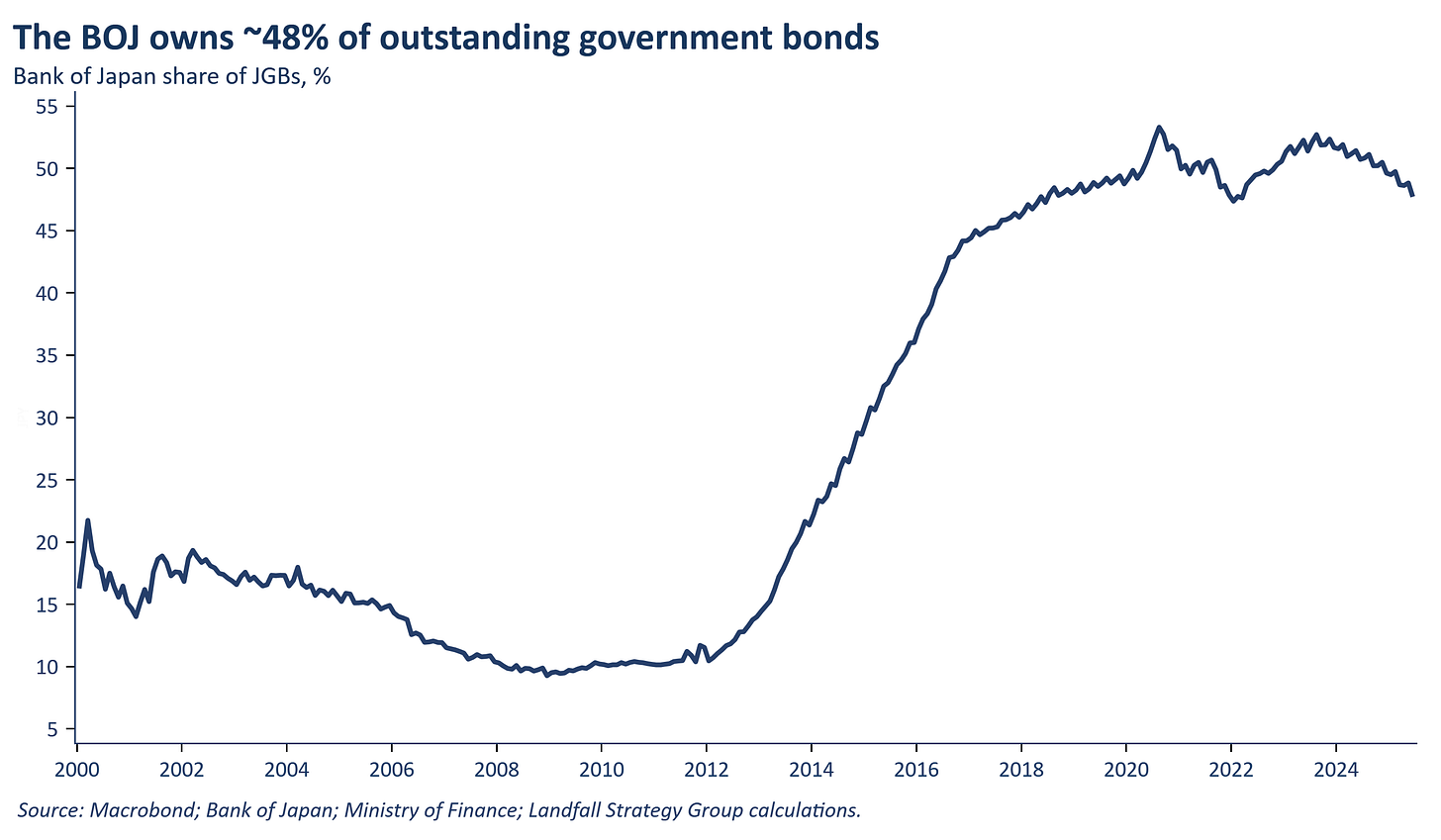

I look at the Fed independence debate primarily through a government balance sheet lens; that it is importantly a response to the financing needs of the US government. Ongoing attempts by the Trump Administration to exert increased political control over the Fed are partly about lowering rates. But it is also likely motivated by a desire to use the Fed balance sheet as an at-scale purchaser of US Treasuries in the context of record levels of public debt; to relax the government’s budget constraint by expanding the pool of demand for US Treasuries. This is a move towards ‘fiscal dominance’, a marked shift in US macro policy. The Japanese model provides some guidance on what this might look like: ~80% of the Bank of Japan’s large balance sheet (total assets of ~110% of GDP) is made up of Japanese government bonds. The Bank of Japan owns a remarkable 48% of outstanding Japanese government debt; the equivalent number for the Fed is 11%. We should be watching for a more fundamental shift in US macro policy than simply policy rates that are lower than otherwise.

5. Investing under duress

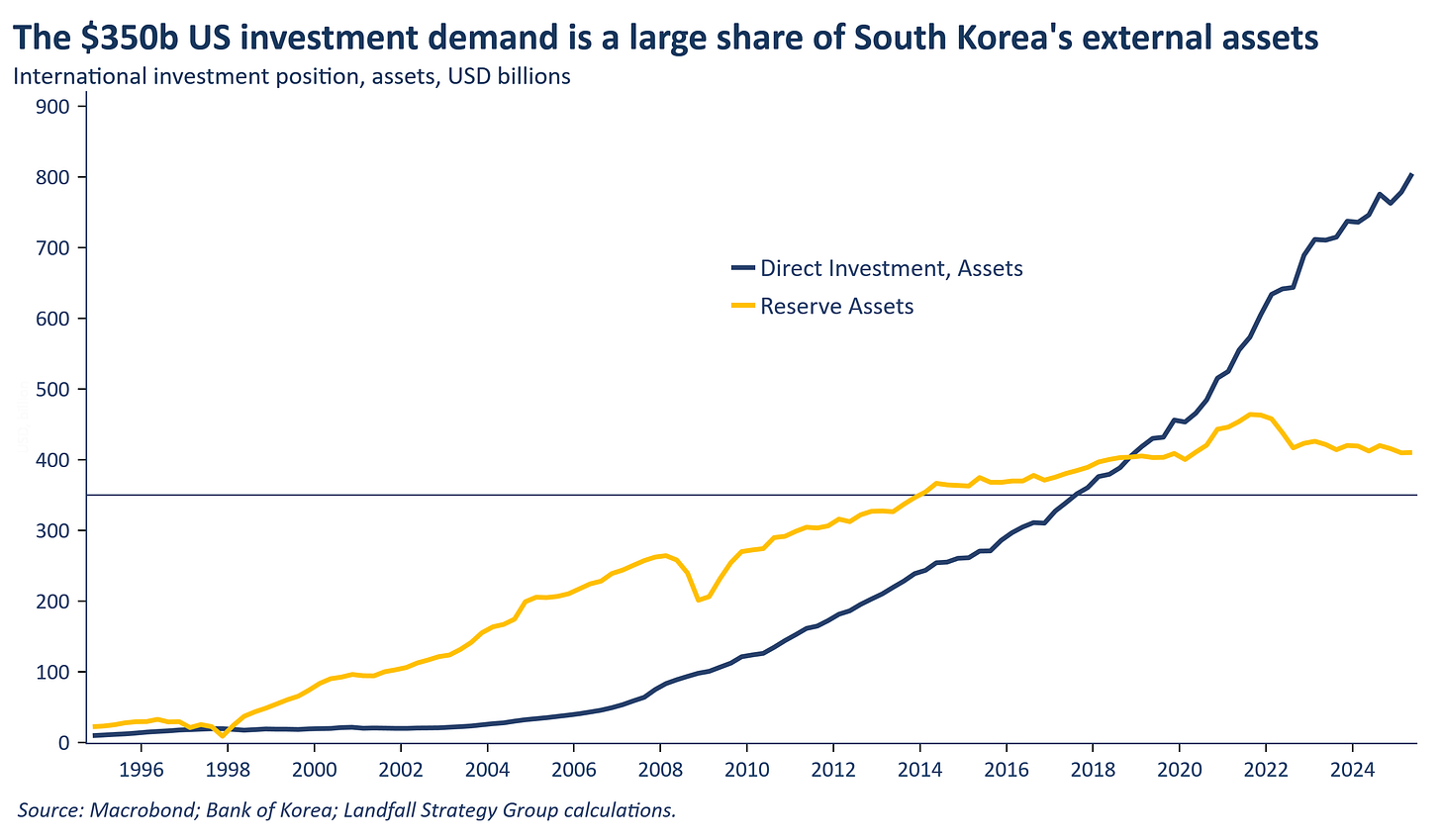

The US is also seeking to attract foreign capital through demanding investment commitments in the context of tariff negotiations: firms and countries (from the Gulf, the EU, Asia and elsewhere) have committed hundreds of billions in investments to reduce tariff exposure. Many of these commitments are exaggerated. However, the aggressive US demands for capital are also running into real constraints. The demands made of South Korea require US investment of $350 billion into strategic priorities determined by the Trump Administration, and with the profits flowing largely to the US. I think that there is a decent chance that this deal will unravel; and possibly the Japanese deal also, which requires $550 billion of investment into the US. This investment is equivalent to >80% of South Korea’s forex reserves and >40% of their existing outward FDI stock. There is an argument that South Korea is better advised to absorb the cost of the tariffs and use this capital domestically. And more broadly, the US is seen as a less attractive investment location – reinforced by the recent ICE detention of South Korean workers in the US. There are limits to what the US can demand in terms of foreign capital allocation.

6. The curious case of the Argentinian bailout

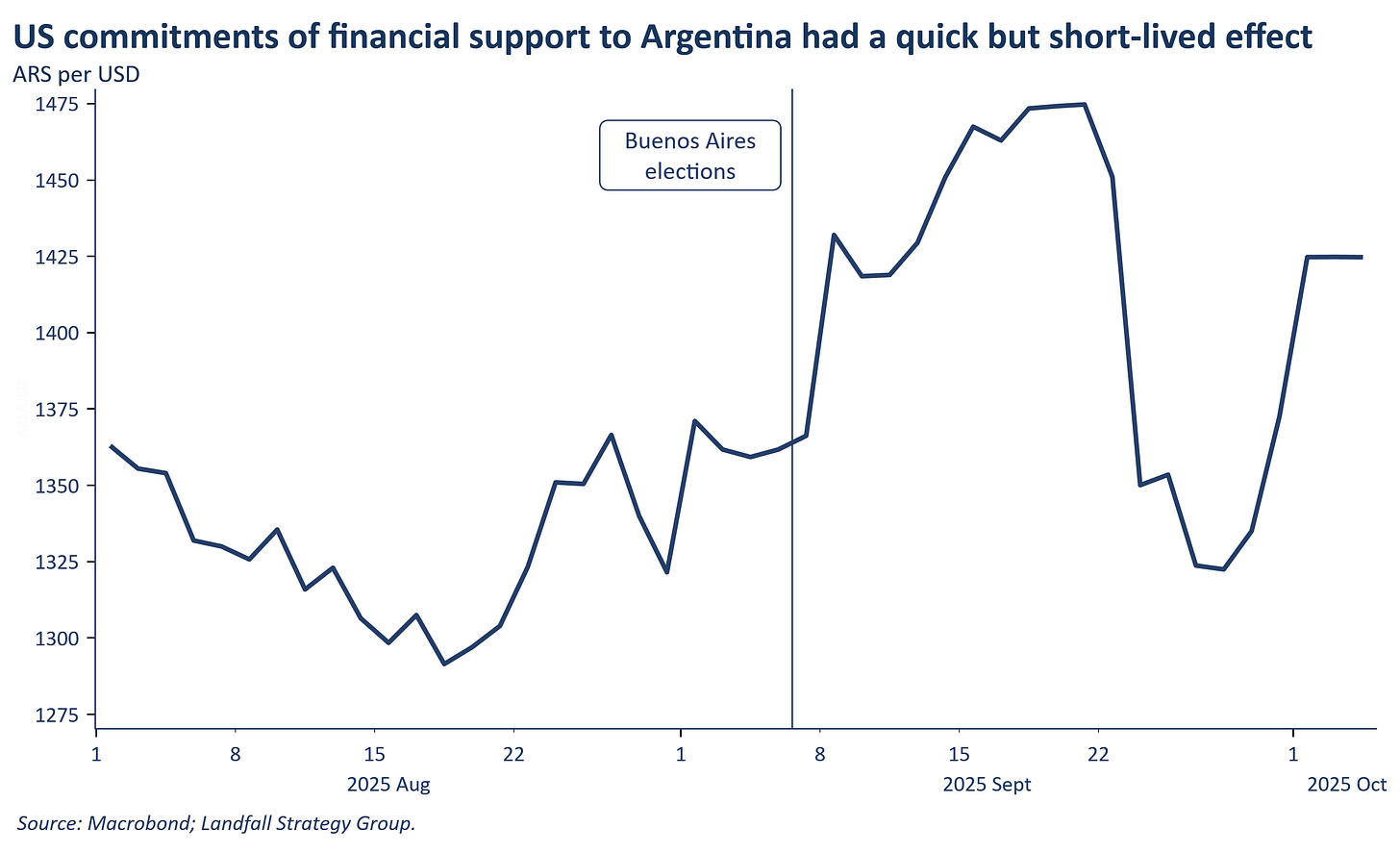

The Argentinian market sell-off after local elections that went badly for President Milei elicited a quick response from the Trump Administration. Secretary Bessent declared Argentina a ‘systemically important ally’ and committed to do whatever it took to support Argentina. There are two broader takeaways. First, it suggests that extension of US financial support (such as USD swap lines) is likely to be conditioned on political affiliation with the White House; it is unlikely that Brazil would have been afforded this support. This reinforces growing concerns that the willingness of the US to backstop the broader global financial system has weakened. Second, that US domestic politics limits the extent of support: Argentina’s markets sold off again as it became clear that US help would be smaller and more short-term than had been initially expected. In an America First world, there are political limits to what the US will do – particularly when China is buying soybeans from Argentina not the US. The perceived weakening of the US backstop increases the likelihood of economic and financial shocks; and will also cause some countries to consider the extent of their reliance on the USD. Indeed, note that Argentina already has a swap line with China.

7. Fiscal v geopolitical strength

The gathering of US military leadership in the same week that the federal government was shut down is a reminder of the relationship between fiscal strength and geopolitical force projection. Governments need to be able to fund their militaries, something that Europe is currently grappling with. But this is increasingly a US issue as well. As I have noted previously, US debt servicing costs now exceed military spending; a dynamic that is likely to continue as interest rates and the debt stock increase. US fiscal issues are becoming a vector of strategic exposure. It was striking that the remarks of the President and of Secretary Hegseth to US military leadership made no substantive mention of China or Russia, but did discuss the domestic deployment of US troops. Mr Trump wants to reset US geopolitical and economic engagement on America First terms, likely with a lower price tag. This is turn has implications for the strength of the reserve currency status of the USD over time.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

5 Comments

Something about the death of the old and the new yet unborn.....what a shit show.

Much of what Mr Skilling once took for granted, is now up in the air.

I bet he's thinking hard.

Great graphs.

Japan is an interesting counter example to the general hysteria about debt to GDP. Most Japanese bonds are purchased by local savers and by the reserve bank. Debt to GDP is 250% and Japan should be an absolute economic catastrophe based on standard economic belief systems. An economic wasteland and destitute ... but it is isn't at all.

Is MMT right? Bonds are just private sector savings not a threat to the economy. The amount of savings (bonds) is an asset to the private sector - not a debt.

Not if there's nothing - or trending less than before - to buy.

"Is MMT right? Bonds are just private sector savings not a threat to the economy."

MMT is both right and wrong (IMO).

Bonds per se are not a problem but it ignores the subsequent effects....such as cross currency trade and distribution.

Great for a self sufficient economy, of which at current expectations dont exist.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.