By Bernard Hickey 'Second tier' ratings agency Fitch is currently reviewing New Zealand's AA+ foreign currency credit rating. Here's 10 reasons below why it should downgrade New Zealand's rating. Standard and Poor's wimped out. Let's hope Fitch doesn't. We certainly need a lower currency and higher retail interest rates and a credit rating downgrade would probably trigger big moves in both. These would help re-balance our economy away from consumption to production, and away from investing in property to investing in exporting. At the moment we seem locked in a no-man's land of a high currency, low interest rates and a 'deja-vu all over again' feeling that we can go back to the foreign debt fueled spending that got us into this mess. Even Reserve Bank Governor Alan Bollard has begun warning about consumers and homeowners returning to their bad old habits. Unfortunately, his warnings are toothless while he leaves the Official Cash Rate at a record low of 2.5%. His failed warning to foreign exchange markets this week that he may cut the OCR if the New Zealand dollar didn't fall is proof we need something more. We need a credit rating reduction. Here's why Fitch should pull the trigger.

By Bernard Hickey 'Second tier' ratings agency Fitch is currently reviewing New Zealand's AA+ foreign currency credit rating. Here's 10 reasons below why it should downgrade New Zealand's rating. Standard and Poor's wimped out. Let's hope Fitch doesn't. We certainly need a lower currency and higher retail interest rates and a credit rating downgrade would probably trigger big moves in both. These would help re-balance our economy away from consumption to production, and away from investing in property to investing in exporting. At the moment we seem locked in a no-man's land of a high currency, low interest rates and a 'deja-vu all over again' feeling that we can go back to the foreign debt fueled spending that got us into this mess. Even Reserve Bank Governor Alan Bollard has begun warning about consumers and homeowners returning to their bad old habits. Unfortunately, his warnings are toothless while he leaves the Official Cash Rate at a record low of 2.5%. His failed warning to foreign exchange markets this week that he may cut the OCR if the New Zealand dollar didn't fall is proof we need something more. We need a credit rating reduction. Here's why Fitch should pull the trigger.

1. Our current account deficit is WAY too high  Some economic apologists for our high debt and our insanely priced property market say that the current account deficit doesn't matter. They argue that there's nothing wrong with foreign investment and foreign lending to fund consumption and investment. They argue that it's all fine because it shows foreign investors have confidence in us and there's nothing wrong with a young country that uses capital well being helped by foreigners. That's true. It's all fine until they lose confidence that we have the ability to keep servicing our debts and paying our dividends to foreign shareholders. Our growth rate is not high either, unlike 'young' countries like China and Brazil. In other words, the current account deficit doesn't matter until does. And it should now. We have been running a current account deficit of more than 8% for near 5 years. When I was a young and thin watcher of the financial markets I was told that anything over 6% is fatal and will turn any self respecting developed country into a 'banana republic'. In theory it is improving, but one look at this chart combined with the signs of recovery in the housing market is reason enough to downgrade us on sight. 2. Our foreign debt has blown out and is accelerating.

Some economic apologists for our high debt and our insanely priced property market say that the current account deficit doesn't matter. They argue that there's nothing wrong with foreign investment and foreign lending to fund consumption and investment. They argue that it's all fine because it shows foreign investors have confidence in us and there's nothing wrong with a young country that uses capital well being helped by foreigners. That's true. It's all fine until they lose confidence that we have the ability to keep servicing our debts and paying our dividends to foreign shareholders. Our growth rate is not high either, unlike 'young' countries like China and Brazil. In other words, the current account deficit doesn't matter until does. And it should now. We have been running a current account deficit of more than 8% for near 5 years. When I was a young and thin watcher of the financial markets I was told that anything over 6% is fatal and will turn any self respecting developed country into a 'banana republic'. In theory it is improving, but one look at this chart combined with the signs of recovery in the housing market is reason enough to downgrade us on sight. 2. Our foreign debt has blown out and is accelerating.  Our debt to GDP ratio has blown out by nearly 20 percentage points to 141% in two years. Mull that over. If we keep going at that rate we'll hit over 200% of GDP within 4 years. We managed to control it reasonably well around the 100% mark for 15 years until 2005 when it got out of hand. The problem is we currently spend about 17% of our export receipts on debt servicing and our exports are falling. The debt is not falling. It's actually rising faster and the interest costs of this debt are likely to rise too over the next five years. It's simply not sustainable. Only Hungary and Iceland had higher debt-gdp ratios last year. Hungary received a US$25 billion rescue package from the IMF last year and Iceland....well we all know what happened to Iceland. 3. The fiscal deficit is about to go very pear-shaped

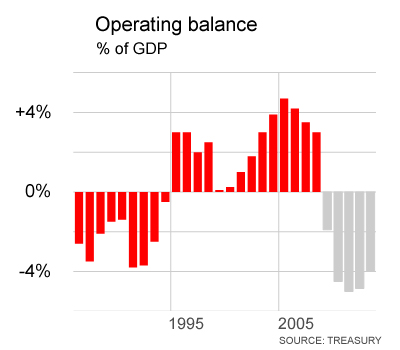

Our debt to GDP ratio has blown out by nearly 20 percentage points to 141% in two years. Mull that over. If we keep going at that rate we'll hit over 200% of GDP within 4 years. We managed to control it reasonably well around the 100% mark for 15 years until 2005 when it got out of hand. The problem is we currently spend about 17% of our export receipts on debt servicing and our exports are falling. The debt is not falling. It's actually rising faster and the interest costs of this debt are likely to rise too over the next five years. It's simply not sustainable. Only Hungary and Iceland had higher debt-gdp ratios last year. Hungary received a US$25 billion rescue package from the IMF last year and Iceland....well we all know what happened to Iceland. 3. The fiscal deficit is about to go very pear-shaped  Up until now one of New Zealand's two saving graces has been the apparent strength of the government's fiscal position. (The other one is our Australian-backed and strong banks) All through the run up in foreign debt from 2004 to 2009 the government was largely not adding to this debt. That's, of course, important for any rating agency because the sovereign rating is for the government's debt. But that benign outlook has gone up in smoke thanks to a quiet build up in government spending over the last 3 years in particular and the not-so-quiet expansion in the last year as the government spends heavily on infrastructure and various job creation and social welfare projects. This chart shows the underlying budget position once interest payments and dividend receipts are taken out. It shows the underlying deficit is likely to be worse than it was in the early 1990s. The government expects to borrow NZ$50 billion over the next 4 years. That's equivalent to 30% of GDP of borrowing from the government alone. And we're currently not projected to be in a significant surplus until nearly 2020. Britney Spears will be a grandmother by then. 4. Our economy is horribly unbalanced

Up until now one of New Zealand's two saving graces has been the apparent strength of the government's fiscal position. (The other one is our Australian-backed and strong banks) All through the run up in foreign debt from 2004 to 2009 the government was largely not adding to this debt. That's, of course, important for any rating agency because the sovereign rating is for the government's debt. But that benign outlook has gone up in smoke thanks to a quiet build up in government spending over the last 3 years in particular and the not-so-quiet expansion in the last year as the government spends heavily on infrastructure and various job creation and social welfare projects. This chart shows the underlying budget position once interest payments and dividend receipts are taken out. It shows the underlying deficit is likely to be worse than it was in the early 1990s. The government expects to borrow NZ$50 billion over the next 4 years. That's equivalent to 30% of GDP of borrowing from the government alone. And we're currently not projected to be in a significant surplus until nearly 2020. Britney Spears will be a grandmother by then. 4. Our economy is horribly unbalanced  Over the last 5 years consumers borrowed heavily from overseas (via our banks) to invest in property and to spend up large on holidays, cars, flat screen TVs and renovations. That meant much of the growth in economic activity was focused on the non-tradeable domestic sectors, rather than the tradeable export and import-substitution sectors. We have not produced any net new jobs in exporting in the last decade. This chart is a damning indictment of our economic performance over the last 5 years and is the reason why our debt has blown out. This meant there has been little development of our export sector. Remember, the only way we can service our debts is by earning foreign exchange...or printing money. 5. Our fiscal position will worsen after 2020

Over the last 5 years consumers borrowed heavily from overseas (via our banks) to invest in property and to spend up large on holidays, cars, flat screen TVs and renovations. That meant much of the growth in economic activity was focused on the non-tradeable domestic sectors, rather than the tradeable export and import-substitution sectors. We have not produced any net new jobs in exporting in the last decade. This chart is a damning indictment of our economic performance over the last 5 years and is the reason why our debt has blown out. This meant there has been little development of our export sector. Remember, the only way we can service our debts is by earning foreign exchange...or printing money. 5. Our fiscal position will worsen after 2020  Just like a lot of other developed countries, New Zealand has its own bulge of baby-boomers about to hit the pension teat, the hospitals and the retirement homes from around 2015 onwards. These pension and healthcare costs will escalate sharply and neither the government nor the public have saved enough to handle it, particularly given both our health and pension systems are open to all and pay as you go. Either some form of rationing will be required (means-tested access to both pensions and health care) or higher taxes will be needed, both of which will suppress growth and our ability to service our debts. Our longevity rates are rising, our birth rates are falling, immigration is relatively low and we have a long term exodus of the working age groups from New Zealand. The ratio of workers to dependents is likely to hit 1 to 1 by 2020, from 1.5 now and 2.5 only 5 years ago. 6. Our productivity performance is awful

Just like a lot of other developed countries, New Zealand has its own bulge of baby-boomers about to hit the pension teat, the hospitals and the retirement homes from around 2015 onwards. These pension and healthcare costs will escalate sharply and neither the government nor the public have saved enough to handle it, particularly given both our health and pension systems are open to all and pay as you go. Either some form of rationing will be required (means-tested access to both pensions and health care) or higher taxes will be needed, both of which will suppress growth and our ability to service our debts. Our longevity rates are rising, our birth rates are falling, immigration is relatively low and we have a long term exodus of the working age groups from New Zealand. The ratio of workers to dependents is likely to hit 1 to 1 by 2020, from 1.5 now and 2.5 only 5 years ago. 6. Our productivity performance is awful  Our ability to increase the amount of GDP per hour worked has been woeful over the last decade, as this chart shows. It is the core driver of our ability to service our foreign debts and grow the economy without inflation. The government has launched a 2025 Taskforce to boost productivity and close the gap with Australia, but any serious reform is utterly dependent on the political will to take some tough decisions. There is little indication these options will be taken. Prime Minister John Key has already ruled out some of the tough options, including a capital gains tax and an extension of the retirement age. 7. Our banks and consumers show no signs of changing Despite a big scare last year, our banks and consumers have fallen back into the same old habits of borrowing overseas to invest in residential property and farming. New Zealand banks lent an extra NZ$545 million to the agriculture sector in June. This was not to expand production or productivity. This was to pay the interest payments on the previous debt taken out with banks. This is capitalising interest via overdrafts. Lending to businesses fell NZ$361 million from May as banks wind back facilities and impose new covenants. They have also left business lending rates at nearly 10% while the OCR fell to 2.5%. Housing lending rose NZ$192 million, thanks to interest rates falling to 6% from close to 10%. 8. Commodity prices are falling and output is flat at best

Our ability to increase the amount of GDP per hour worked has been woeful over the last decade, as this chart shows. It is the core driver of our ability to service our foreign debts and grow the economy without inflation. The government has launched a 2025 Taskforce to boost productivity and close the gap with Australia, but any serious reform is utterly dependent on the political will to take some tough decisions. There is little indication these options will be taken. Prime Minister John Key has already ruled out some of the tough options, including a capital gains tax and an extension of the retirement age. 7. Our banks and consumers show no signs of changing Despite a big scare last year, our banks and consumers have fallen back into the same old habits of borrowing overseas to invest in residential property and farming. New Zealand banks lent an extra NZ$545 million to the agriculture sector in June. This was not to expand production or productivity. This was to pay the interest payments on the previous debt taken out with banks. This is capitalising interest via overdrafts. Lending to businesses fell NZ$361 million from May as banks wind back facilities and impose new covenants. They have also left business lending rates at nearly 10% while the OCR fell to 2.5%. Housing lending rose NZ$192 million, thanks to interest rates falling to 6% from close to 10%. 8. Commodity prices are falling and output is flat at best  The New Zealand dollar prices of the commodities we produce have fallen from their peaks and will continue to fall while the rest of the developed Western world goes through an extended period of debt-deleveraging and switching from debt-driven consumption to savings-driven production. The rise in the New Zealand dollar and higher agricultural production costs (largely due to inflated land costs) are causing farmers to stall any growth in dairy output, which is now the dominant export earner. Sheep and beef farmers are doing OK after years of winding back output, although they are now focusing any growth on servicing the dairy sector with runoffs. 9. NZ does not have low enough domestic inflation Non-tradeable inflation, which is the inflation linked to the government, retail, infrastructure, telecommunications, banking and other non-export sectors, has been above 3% for most of the last 7 years and is only now dropping back into the Reserve Bank's 1-3% target band for the entire inflation rate. This is all part of our unbalanced economy. We need higher interest rates and a lower currency to help push this inflation back into line over the longer term. 10. We simply are not saving enough

The New Zealand dollar prices of the commodities we produce have fallen from their peaks and will continue to fall while the rest of the developed Western world goes through an extended period of debt-deleveraging and switching from debt-driven consumption to savings-driven production. The rise in the New Zealand dollar and higher agricultural production costs (largely due to inflated land costs) are causing farmers to stall any growth in dairy output, which is now the dominant export earner. Sheep and beef farmers are doing OK after years of winding back output, although they are now focusing any growth on servicing the dairy sector with runoffs. 9. NZ does not have low enough domestic inflation Non-tradeable inflation, which is the inflation linked to the government, retail, infrastructure, telecommunications, banking and other non-export sectors, has been above 3% for most of the last 7 years and is only now dropping back into the Reserve Bank's 1-3% target band for the entire inflation rate. This is all part of our unbalanced economy. We need higher interest rates and a lower currency to help push this inflation back into line over the longer term. 10. We simply are not saving enough  This chart shows that corporates and banks (it's actually mostly banks) are not saving enough. They're still drawing down on foreign debt and the government is about to join the party. It's not sustainable. If we can't make the tough choices for ourselves, a ratings agency and international investors will have to do it for us.

This chart shows that corporates and banks (it's actually mostly banks) are not saving enough. They're still drawing down on foreign debt and the government is about to join the party. It's not sustainable. If we can't make the tough choices for ourselves, a ratings agency and international investors will have to do it for us.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.