This is a re-post of an article originally published on pundit.co.nz. It is here with permission.

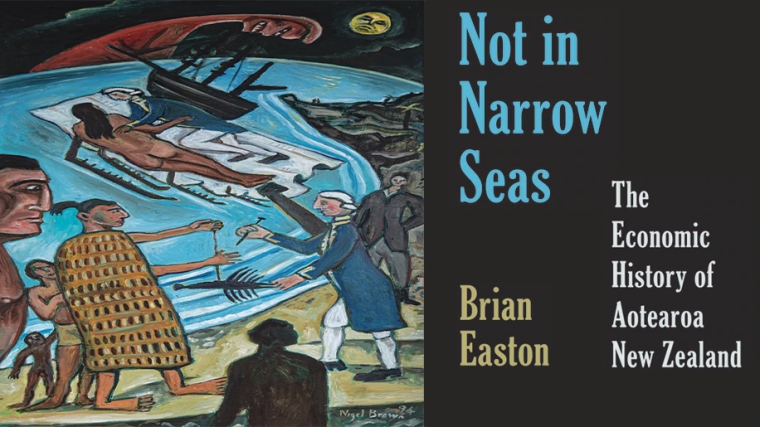

I have been asked what my book, Not in Narrow Seas: The Economic History of Aotearoa New Zealand, out this month, says about the Covid Crisis. The short answer is nothing ... and everything.

Not in Narrow Seas was sent to the printers before the lockdown – before the government had even made up its mind – so Covid19 did not make the history. Historians are no better at predicting the future than economists or weather-forecasters (which puts them ahead of commentators and politicians).

The book does deal with previous major epidemics. Surprisingly, the most important epidemics in New Zealand’s histories have been hardly mentioned in recent months. Yet dysentery, influenza, measles, STDs and whooping cough swept through the immunologically virgin Maori population in the nineteenth century, killing more than warfare did. Add the sterility they also caused and the Maori population collapsed. Fortunately, enough Maori survived and the population recovered, but had they not been decimated by the diseases, the history of New Zealand would have been quite different.

We pay a lot more attention to the wars of the nineteenth century; I suppose they are more heroic. But we should not neglect the epidemics or remain as insensitive to them as one observer who remarked at the time that some late-nineteenth-century waves were ‘mild’ because few Maori ‘succumbed’ to the disease ‘except for children’.

(To make an observation, not merely as an aside, we have to be grateful to Ian Pool for his sterling research in this area, and on Maori – and non-Maori – demography generally. General histories are dependent on the work of meticulous scholars like him. I am so grateful to them.)

The book also discusses the 1918 influenza epidemic which is better documented and leaves a clear mark on the data – now of better quality than nineteenth-century statistics. A greater impact was on Samoa, where 22 percent of the population succumbed – including leaders who might have changed the course of the Mau independence movement. (The book has a chapter on the history of the Pacific Island economies – reflecting a view that we should include a history of where we came from; there are two chapters on Britain and one on the islands the ancestors of the Maori left from.)

In the early stage of the Covid Crisis I was fascinated by its evidence of (often temporary) international mobility. The book I wanted to change was my 2006 Globalisation and the Wealth of Nations which was much troubled by the meaning of nationalism in a population-mobile world. Mind you, if we were doing a second edition I would add more about the diminishing American hegemony. Certainly Donald Trump’s thrashing around is contributing to it but he is responding to his uncomprehending electorate; I saw the same thing as Britain’s world role diminished, although they never descended to a Trump-like leader (even if Boris Johnson has tried).

Fear not, both the nationalism and new world order are also covered in Not in Narrow Seas but not in as much detail. It was damned difficult to pack everything into a quarter of a million words (the first draft was nearer 400,000) as I tried to cover everything from Gondwanaland – when New Zealand was formed – to the Ardern-Peters Government and climate change.

But do not expect a definitive overview of the current government. Histories always struggle with recent events because the real value of a history – other than the factual narrative – is its reflection on the past and the learnings it offers. As I have already said, not the predictions, but each reader will, I hope, use the book not only to give themself a better understanding of where we came from and how we got here, but also to think about the future.

From the study one might ponder on whether the Covid Crisis is another decisive moment in our history. Aside from the nineteenth century, I have gone back to the impact of the Great Depression and the Second World War on the course of New Zealand, and the 1966 Wool price crash, which led to the neoliberal revolution of the 1980s and 1990s, which set New Zealand on an entirely different course (I think, although the book sets out the debate of the extent to which it did).

I was surprised that the Global Financial Crisis did not result more in a redirection of the international course. Perhaps the Covid Crisis will reinforce the GFC lesson that a minimalist approach, which emphasises the market at the expense of the state, does not always lead to quality human wellbeing. I guess that will be explored in the second edition of Not in Narrow Seas – supposing there is one. In the interim I hope the book will enable you to explore such questions yourself.

PS. If you would like a further taste of the book, you can read its introduction on pages 131-143 of the (free) VUP Home Reader. Happy reading.

(Not in Narrow Seas is published in May, with the ebook available now from mebooks New Zealand eBooks; the print edition will be at your local bookshop once we are in Alert2.)

Brian Easton, an independent scholar, is an economist, social statistician, public policy analyst and historian. He was the Listener economic columnist from 1978 to 2014. This is a re-post of an article originally published on pundit.co.nz. It is here with permission.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.