Here's my Top 10 items from around the Internet over the last week or so. As always, we welcome your additions in the comments below or via email to bernard.hickey@interest.co.nz.

See all previous Top 10s here.

My must-read today is #5 from Paul Mason on how the future of capitalism depends on the response of voters to changes in migration and technology.

1. It's quiet...too quiet - Tim Harford writes well here at the Undercover Economist about the amazingly low volatility on global financial markets at the moment.

It's the reason why Spanish bond yields are at their lowest levels since the late 1700s and why the New Zealand dollar is at post-float highs.

It's also why (or a consequence of) global stock markets are near record highs.

That's despite continued and frustratingly low economic growth in most of the developed world, big problems in the Middle East and a risk of a China shadow banking crisis.

Investors seem convinced that there is very little risk, and even if there is, central banks will bail them out time and again with fresh bouts of money printing.

Harford takes a nuanced view that it's either a sign of impending disaster or the necessary pre-condition for recovery.

Here's his thinking:

There is a commonsense alternative to the idea that this must be the calm before the storm: it’s that no news is good news. So which view is right? Should we treat low volatility as an eerie portent of disaster in the making, or as a sign that the world economy is finally on the right track?

The answer to the question depends on whether we look at financial markets, or at the real economy of goods and services, production and investment.

From a financial perspective, low volatility should indeed make us nervous. That’s the lesson of the late Hyman Minsky. Minsky was once neglected but, since the financial crisis, we are all Minskyites now. Your bluffer’s guide to Minsky is that when things are going well, people become complacent and take too many risks – in particular, the classic leverage risk of borrowing to invest.

Calm breeds complacency. Stability is destabilising.

3. Fundamental vs bubbly collateral - Alberto Martin and Jaume Ventura write at VoxEU about their research into whether and how central banks can 'lean against' "bubbly" asset booms.

It's a good argument for increasing capital requirements for banks and for our Reserve Bank to use its counter-cyclical capital buffer.

An essential feature of bubbly collateral is that its stock is driven by investor sentiment or market expectations. The credit obtained by borrowers today depends on market expectations about the credit that borrowers will obtain tomorrow, which in turn depend on tomorrow’s market expectations about the credit that borrowers will obtain on the day after, and so on. Because of this, markets may sometimes provide too much bubbly collateral and sometimes too little of it, which creates a natural role for stabilisation policies.

We show that a lender of last resort with the authority to tax and subsidise credit can in fact replicate the optimal bubble allocation. To do so, it must adopt a policy of ‘leaning against the wind’ – taxing credit when bubbly collateral is excessive and subsidising it when bubbly collateral is scarce. We show that such a policy raises steady-state levels of output and consumption. It may have ambiguous effects on macroeconomic volatility, though. The reason is that, by managing the economy’s stock of collateral, the policy reduces the responsiveness of credit to ‘investor sentiment’ shocks, but it may enhance the response of credit to standard productivity shocks.

4. Why DSGE models crash during crisis - This is a lot wonky, but Oxford Professor David Hendry writes a critique at VoxEU of the DSGE (dynamic stochastic general equilibrium) model that most central banks, including ours, uses to forecast the economy.

Unanticipated changes in underlying probability distributions – so-called location shifts – have long been the source of forecast failure. Here, we have established their detrimental impact on economic analyses involving conditional expectations and inter-temporal derivations. As a consequence, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models are inherently non-structural; their mathematical basis fails when substantive distributional shifts occur.

Like a fire station that automatically burns down whenever a big fire starts, DSGEs become unreliable when they are most needed

5. Money laundering in Australia via the Bank of China - Business Spectator reports on how China's CCTV has launched an extraordinary attack on the Bank of China over the help it gives to Chinese citizens who want to launder money through Australia's Significant Investor Visa programme.

“We don’t care where your money is from or how you earn it, we can help you get it out of the country,” a Bank of China employee told CCTV. “We don’t care how black your money is or how dirty it is, we will find ways to launder it and shift it overseas for you,” according to a detailed CCTV investigative report.

Australia is a centrepiece of the investigation due to the country’s Significant Investor Visa program, which offers an accelerated pathway for wealthy investors to gain permanent residency by investing $5 million in Australian bonds, funds or a small business. Chinese nationals account for nine out of 10 applicants since the program was introduced under the former Labor government.

Under China’s stringent foreign exchange law, citizens are only allowed to send $US50,000 or $A53,000 abroad per year. Australia has been repeatedly been mentioned as the destination of “grey money” coming out of China in relation to Australia’s significant investor visa program.

6. 'The best of capitalism is over' - BBC Newsnight's Economics Editor Paul Mason writes this fascinating piece at The Guardian about the OECD's recent predictions about the global economy until 2060.

The roles of migration and technology are crucial.

World growth will slow to 2.7%, says the Paris-based thinktank, because the catch-up effects boosting growth in the developing world – population growth, education, urbanisation – will peter out. Even before that happens, near-stagnation in advanced economies means a long-term global average over the next 50 years of just 3% growth, which is low. The growth of high-skilled jobs and the automation of medium-skilled jobs means, on the central projection, that inequality will rise by 30%. By 2060 countries such as Sweden will have levels of inequality currently seen in the USA: think Gary, Indiana, in the suburbs of Stockholm.

To make the central scenario work, Europe and the USA each have to absorb 50 million migrants between now and 2060, with the rest of the developed world absorbing another 30 million. Without that, the workforce and the tax base shrinks so badly that states go bust.

The main risk the OECD models is that developing countries improve so fast that people stop migrating. The more obvious risk – as signalled by a 27% vote for the Front National in France and the riotous crowds haranguing migrants on the California border – is that developed-world populations will not accept it. That, however, is not considered.

Now imagine the world of the central scenario: Los Angeles and Detroit look like Manila – abject slums alongside guarded skyscrapers; the UK workforce is a mixture of old white people and newly arrived young migrants; the middle-income job has all but disappeared. If born in 2014, then by 2060 you are either a 45-year-old barrister or a 45-year-old barista. There will be not much in-between. Capitalism will be in its fourth decade of stagnation and then – if we've done nothing about carbon emissions – the really serious impacts of climate change are starting to kick in.

7. 'Welcome to the everything boom -- And quite possibly the Everything Bubble' - This piece in the New York Times captures the mood of distrust around the current booms in stock, bond and property markets around the world despite stagnant economic growth. It discusses the savings glut and investment drought ideas.

Around the world, nearly every asset class is expensive by historical standards. Stocks and bonds; emerging markets and advanced economies; urban office towers and Iowa farmland; you name it, and it is trading at prices that are high by historical standards relative to fundamentals. The inverse of that is relatively low returns for investors.

The phenomenon is rooted in two interrelated forces. Worldwide, more money is piling into savings than businesses believe they can use to make productive investments. At the same time, the world’s major central banks have been on a six-year campaign of holding down interest rates and creating more money from thin air to try to stimulate stronger growth in the wake of the financial crisis.

But while central banks can set the short-term interest rate, over the long run rates reflect a price that matches savers who want to earn a return on their cash and businesses and governments that wish to invest that savings — whether in new factories or office buildings or infrastructure.

In this sense, high global asset prices could be the result of a world in which there is simply too much savings floating around relative to the desire or ability of businesses and others to invest that savings productively. It is a reassertion of a phenomenon that the former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke (among others) described a decade ago as a “global savings glut.” But to call it that may not get things quite right either. What if the problem is not too much savings, but a shortage of good investment opportunities to deploy that savings? For example, businesses may feel that capital expenditures are unwise because they won’t pay off.

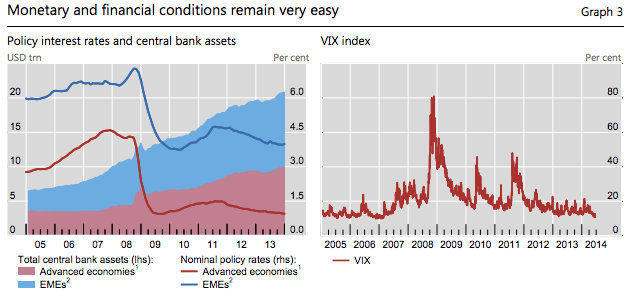

8. 'Deja vu all over again' - The New York Times reports the Bank for International Settlements is, however, worried enough about all this pump priming by central banks simply inflating asset bubbles to sound another warming -- a bit like the one it sounded before the GFC. The chart below tells the story. And here's the speech to go with it.

“During the boom, resources were misallocated on a huge scale,” Mr. Caruana said, according to a text of his speech, “and it will take time to move them to new and more productive uses.”

The organization, which reflects a widespread view among central bankers that they are bearing more than their share of the burden of fixing the global economy, often uses its annual reports to send a message to political leaders, commercial bankers and investors. But the B.I.S.’s language in the 2014 edition was unusually direct, as was its warning that the world could be hurtling toward a new crisis.“There is a disappointing element of déjà vu in all this,”said Claudio Borio, head of the monetary and economic department at the B.I.S.

9. The fossil fuel industry as the new sub-prime crisis - Ambrose Evans Pritchard always talks a good game at The Telegraph. This time he's having a go at the oil and gas industry's recent spending spree.

The epicentre of irrational behaviour across global markets has moved to the fossil fuel complex of oil, gas and coal. This is where investors have been throwing the most good money after bad.

They are likely to be left holding a clutch of worthless projects as renewable technology sweeps in below radar, and the Washington-Beijing axis embraces a greener agenda.

Data from Bank of America show that oil and gas investment in the US has soared to $200bn a year. It has reached 20pc of total US private fixed investment, the same share as home building. This has never happened before in US history, even during the Second World War when oil production was a strategic imperative.

16 Comments

Just commented on NZ's power consumption increase,

http://www.interest.co.nz/news/70868/fed-plans-next-stage-china-sets-mo…

I am watching for June's consumption with great interest. It has been mild weather so if its up a decent % again maybe we are coming out of it a bit...

regards

Re the low-VIX etc and the 'it's too quiet' meme: I've always regarded Doug Noland and Martin Hutchinson as steady voices, and here's what Martin has said recently on this very topic.

"Some of these contracts such as the $584 trillion of interest-rate swaps are not especially risky (except to the extent that traders have been gambling egregiously on the market's direction). However, other derivatives, such as the $21 trillion of credit-default swaps (CDS) and options thereon, have potential risk almost as great as their nominal amount. What's more, there are $25 trillion of “unallocated” contracts. My sleep is highly troubled by the thought of 150% of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in contracts which the regulators can't define!"

And Doug Noland on Janet Yellen: (my bolding)

"After five years, the proliferation of all varieties of instruments, products and strategies have combined with Fed policies and market assurances to create the perception of “moneyness” for all types of risk assets. Endless cheap liquidity, inexpensive risk insurance and profound faith in central bank market backstops have evolved into an all-powerful market phenomenon – I would argue history’s greatest mispricing of finance. And epic misperceptions and securities mispricing remain completely outside the purview of the Fed’s so-called “macroprudential” tools. Dr. Yellen, you just condoned “Terminal Phase” excesses – including one heck of a speculative melt-up/equities market dislocation."

#4: that's rather like saying your car will work most of the time, but not if it is hit by a runaway train. That's not a reason for giving up your car.

If there's a reasonable expectation that you'll get hit by a runaway train then it's a very good arument indeed for finding another vehicle! And with models there's no reason that you can't still use the old one as well.

So what do you think - is there a reasonable expectation that there'll be one of these so called location changes? As far as I can tell, signs point to yes.

#5 money laundering

Business Spectator 9 July 2014

The Bank of China is most powerful government controlled financial institution in China

Business Spectator understands that some private bankers from Australia’s big four banks have been aware of the service for a year.

A senior manager with one of the Big4 Australian banks said Bank of China was crucial to the bank’s migration business

Is that the same as ICBC?

The biggest bank in the world, China's state-controlled ICBC, is setting up in New Zealand

ICBC 9 January 2013

http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/money/8155831/Giant-China-bank-seeks-NZ…

ICBC 19 November 2013

http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/money/9417158/China-banking-giant-lands…

New Zealand happens to have a similar "significant investor program" also

Does one assume the same business arrangements apply in New Zealand?

Wonder what Bernards take is on this.Read article this morning published on th "Business Spectator" .seems to me this is what has been allowed with "no search" for people flying in on SC Airlines to gamble at Sky City.

If it`s true that "a senior manager with one of the big four Australian banks told CCTV reporters that the Bank of China was crucial to the banks migration business,are we to believe that the banks in NZ owned by their ones in Aus,are not facillitating same but different in NZ?

Is our government,driven by the law of the jungle money ways,turning a blind eye to similar practises and at the same time selling our souls ?

Arent we allowed to think that we`ve been morally sold out to whatever the source our so called investment income comes from?

We`re a better people than this type of shenanigans aren`t we?

#4. I went to a talk on DGSEs yesterday. My take on them (rightly or wrongly) is that they are linear approximations of non-linear systems, so it probably shouldn't be too much of a surprise that the post-shock equilibrium is not where they think it should be.

"Is our government,driven by the law of the jungle money ways,turning a blind eye to similar practises and at the same time selling our souls ?

Arent we allowed to think that we`ve been morally sold out to whatever the source our so called investment income comes from?

We`re a better people than this type of shenanigans aren`t we?"

But, ..but, ..not if we keep reelecting a smiling assassin bankster as PM..

#6 "a long-term global average over the next 50 years of just 3% growth, which is low."

Really?

That's a quadrupling of current output. Probably accompanied by a roughly similar growth in energy usage.

It isn't going to happen - at least not without totally destroying the biosphere.

As a rough guide historically a 4% increase in GDP =s a 2.5% increase in energy use. ie we use energy to make things, cant get around that.

regards

"next 50 years of just 3% growth, which is low."

In 50 years there will be no fossil fuel to speak of.

So the entire fossil fuel industry has to be replaced. Even if that is possible that isnt "growth" it is a swapout.

regards

What a Math failure,

3% per annum growth btw = 70/3 = 23. So the world economy doubling every 23 years, or in 50 years it will be 4 times (roughly) the size it is today.

Consider what that means in terms of energy demand, population and stress on the eco-system.

Then consider what that means for AGW.

It is far more likely that we'll be at 2billion or less in 50 years, (actually I suspect 20~30 years). As the "Green revolution" was all about turning fossil fuels into food, no more fossil fuels, no more food.

regards

"or a 45-year-old barista. ....... if we've done nothing about carbon emissions – the really serious impacts of climate change are starting to kick in."

You think by then there will even be a sizable coffee crop as such?

hmmm.

Oh and who will be left with enough $s to afford to pay barristers? and how many will be needed?

I think not.

regards

You really do have to wonder if the likes of Bernanke &Co really do understand the system they're suppoesd to control. Global Savings Glut; WTF?

In case he wasn't aware we have a credit/debt based money system; allow that to expand at 10% a year and you're going to have a 10% increase in savings to balance the increase in debt. If the economy expands at half or less that rate you're pretty soon going to have a pile of "savings" that are impossible to absorb - even with interest rates at multi century lows.

What's so hard to understand about that?

I don't understand why people are still surprised by the economy's inability to deploy all that capital. It's like they think that things ought to magically just work. It's not as if you need to be able to see into the future to understand that. Heck you barely even need to be able to see into the present anymore - it's been happening for best part of a decade now! Or three decades, when you include the long slow pileup of household debts. Households don't have enough money to buy more things. Simple as that.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.