By David Norman*

- A recent bi-partisan announcement brings forward and widens the coverage of more relaxed development rules across high growth cities in New Zealand.

- The changes will allow even more compact (particularly residential) development, which means lower emissions and congestion growth than the alternative.

- But caveats, called “qualifying matters”, could limit the benefit of these changes if the wrong trade-offs are made.

- An objective way of evaluating qualifying matters and practical ways to pay for supporting infrastructure are desperately needed.

On 19 October, the government and opposition jointly announced a plan to accelerate implementation of the National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD), to sharply increase density around city centres, town centres and rapid transit stations. Further, the new rules will increase potential density on an even wider range of properties across high growth cities.

A lot of good news

I argued for increased density for several years and was more welcoming of the original NPS-UD than some. This newly-announced expansion and acceleration must be applauded on a number of fronts.

First, the new rules will stimulate more development closer to jobs, existing public transport and amenities. i.e., where more people want to be. We have already seen a remarkable shift toward brownfield (existing urban area) development and away from far-flung greenfield development as Auckland’s current zoning rules came into force from 2016. In the five years since, 90% of all growth in new dwellings consented in our largest city has been in predominantly brownfield areas, and only 13% of new dwellings consented in total in the year to June 2021 were in predominantly greenfield areas.

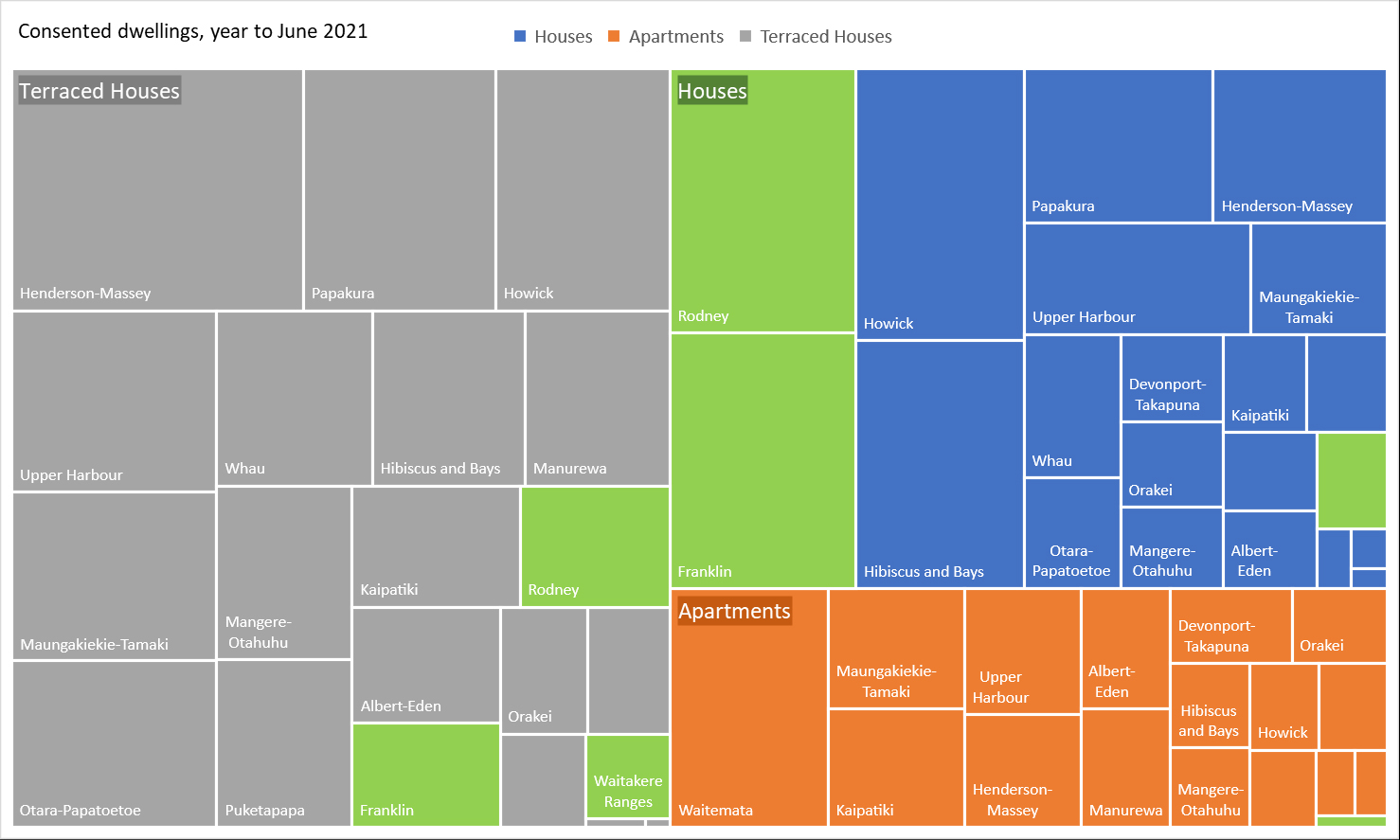

Figure 1 Given choice, people prefer proximity to the city (predominantly greenfield Local Boards shown in green)

Second, development in existing urban areas uses existing infrastructure more efficiently. It is true that the increased density will also trigger demand for more infrastructure, but in areas where latent capacity exists, that will be used first. Existing brownfield areas are also where most new infrastructure is being delivered, such as the City Rail Link in Auckland, which offers huge development potential in areas around Mt Eden for instance.

Third, more development around town centres, rapid transit nodes and wherever land prices (the best indicator of demand) are high, adds to the vibrancy of those neighbourhoods. More housing attracts a wider range of goods and services into communities, bringing improved safety through a more substantial night-time economy, for example.

Fourth, compact development means lower emissions and congestion per home delivered. In Auckland, for instance, more permissive zoning has shifted the share of multi-unit dwellings consented (terraced houses and apartments) from 41% in 2016 to 64% today.

Still too much leeway?

The newly announced rules[1] still allow for local “qualifying matters” to prevent relaxation of zoning rules to deliver more housing under certain circumstances for the purpose of:

- ensuring the safe or efficient operation of nationally significant infrastructure

- open space provided for public use

- an area subject to a designation or heritage order

- consistency with iwi participation legislation

- sufficient business land suitable for low density uses

- any other matter that makes high density development inappropriate in an area.

This list of extenuating circumstances allows for a fair bit of subjective interpretation, particularly the point about “any other matter that makes high density development…inappropriate”. The NPS-UD does require that if these exemptions are employed, some justification must be provided, including a site-by-site analysis. The exemption needs to be appropriate “in light of the national significance of urban development”, but “appropriate” is still left up to the individual authority to define and defend.

Real-life implications: less housing where it is most valued

In the Auckland context, two main qualifying matters that opponents of more density in their neighbourhoods appeal to are “special character” and “volcanic viewshafts”. The special character rationale has also been applied in Wellington and will likely crop up in other high growth cities.

A criticism of Auckland’s 2016 zoning rules was that it left so much low density zoning closest to the city centre. Around 30,000 mostly central dwellings (about one out of every 18 Auckland homes) were deemed to be of “special character” during that rezoning process. Because these rules restrict development closest to jobs, public transport, and amenities, they also force the city to develop in a more congested, car-oriented, higher emissions way.

Further, the city has preserved over 80 volcanic viewshafts, sometimes from obscure places (such as from vehicles driving south on Highway 1 toward the city centre), and often limiting development in highly desirable parts of the city where housing could be closer to jobs, public transport and other amenities. Viewshafts are not about protecting access to these sites, which have cultural, environmental, and social value, but effectively determine how many people should be able to see volcanoes and from where.

Figure 2 Auckland’s special character areas and volcanic viewshafts, mostly close to the city centre

As an economist, I help clients evaluate trade-offs. In this instance, we must ask how much we want to limit people accessing homes closer to jobs, public transport and other amenities to protect these other valued things. Preserving “best in class” historical buildings and the most prominent volcanic views undeniably has value, but so does housing more people safely, and closer to jobs, public transport and amenities. What is the right number of protected properties to preserve part of our history? The answer is likely much less than 30,000, but is it 2,000 or 6,000? Or what is the right number of viewshafts to protect iconic views?

At present, these questions, which could be replicated in other parts of the country and for other qualifying matters, such as “outstanding natural landscapes”, are seldom answered objectively. In recent years, the price premium (a good measure of value) people pay for special character properties has declined, while that for properties receiving denser zoning has grown.[2] This implies that the value of homes with special character status may be accruing to those around them, who don’t want more development in the neighbourhood, rather than to the property owner. Meanwhile, those actually purchasing properties find ones with more development potential more attractive.

We are unlikely to remove NIMBYism from the debate without a pragmatic approach to trading off these values. This could include a contingent valuation or similar experiment, where answers can’t be gamed, and where the number of people signing an online petition that does not tackle the implied trade-offs of their preferences is not used as the basis of decision-making.

Real-life implications: two infrastructure challenges

There are two further, infrastructure-related problems related to the announcement. First, the assumption is that properties covered by the new relaxed zoning will be adequately infrastructured. But infrastructure is eye-wateringly expensive, and councils have traditionally not charged the full price of new infrastructure to the properties that benefit from it. Encouraging signs have emerged from Hamilton and now Auckland of development contributions that come closer to the true cost of development infrastructure. But there is a huge gap yet to overcome across high growth councils, and at present no clear plans to fund the gap.

Second, the socialising of private costs of development (one reason for the existence of NIMBYism) is seldom factored into development decisions. For instance, as special character overlays have forced development further from the city, burgeoning new multi-unit development in Auckland’s sellers’ market often socialises private infrastructure costs. An example is parking, often underprovided on private properties (yes, distance from the city means most people still need a car), leading to people socialising those costs by parking on berms, pavements, and across driveways, reducing safety for pedestrians and drivers, and pushing amenity down.

To end, a plea or two

In deciding what qualifies as a reason not to deliver more housing, we must provide empirical, data driven evidence that we are making the right trade-offs.

And with more upzoning due by next September, high growth councils need to have funding policies in place before going out to consultation on how and where zoning will be relaxed. These policies need to demonstrate the large windfall gain properties will likely receive as the upzoning lever is pulled. The policies also need to clarify how part of those gains will fund the infrastructure needed to make development successful, including internalising costs that would otherwise be borne outside the development.

* David Norman is an Executive Advisor in Economics and Strategy at GHD. This article is here with permission. You can contact him here.

21 Comments

"the large windfall gain properties will likely receive". That's all that matters.

"the infrastructure needed to make development successful, including internalising costs that would otherwise be borne outside the development." Not 'that would otherwise' - will.....

The entire article can be summarised in 2 words.

Be quick.

There's some flaws in his thinking. It's rather simplistic.

One of the biggest ones is the assumption that the Housing Supply Bill is good for emissions. I am not sure it is.

Because it basically will enable higher density housing almost everywhere in our biggest cities. This means the potential for lots of ad hoc development in far flung locations well removed from good public transport.

This means a lot of the housing generated will still be heavily reliant on cars.

It depends on how dense we can make population centres. If you just get increasing subdivision then it'll be low impact because Auckland, for example, only has a population density of 1,210 people per square kilometre. Typically cities are looking for around 5000+ people per square kilometer to really get to those cities where people walk or use public transit systems day-to-day.

Auckland population, currently 1.66m, is likely to increase by 0.65m by 2048 according to stats NZ so unfortunately just "building out" won't be nearly enough to get to that density even if every new residence was within the existing city boundary.

Much as to say that what has been struck upon is a messy compromise because we didn't want to substantially improve the RMA as a planning tool.

The Housing Supply Bill will disincentivise high density development near centers and train stations, which is pretty bad if you want people to use cars less and use public transport, walking and cycling more.

Why build apartments which are costlier and higher risk when you can whack up a few townhouses at lower risk and with greater financial return in the middle of suburbia?

He's right on the large windfall gains coming as a result of the changes, something I have been touching on for months, and something I have said could help support higher median house prices.

Overall this effectively increases the supply of land, which will reduce the relative value of land. The areas that are highly sort after for increased density will go up in value, but overall this will be a downward pressure on land values.

In theory yes, not so much in reality.

The Unitary plan has enabled a lot of density in many locations, yet land values have soared. Might they have soared more without it? Maybe.

Theoretically, the extra abundance of density potential might limit the extent of land value inflation.

But there's a lot of factors beyond zoning that affect supply in existing urban areas. Things like the size of sections, the age and quality of the housing on them, ownership structure, slope, presence of hazards, access to and availability of infrastructure etc. all mean that readily redevelopable sites are a fairly small subset of all sites zoned for higher density. The other reality is that many owners of property don't want to redevelop, or don't have the means to do so.

I guess it will be interesting to see how reality plays out against theory.

Essentially, the argument made is for betterment (planning gains) to be paid for by the developer as per the legislation in the UK;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planning_gain

But why limit such a charge to development only. I think we need to go further with this thinking and expand consideration of both betterment and worsenment (planning gains and losses) as a method for determining property rates (i.e., across all property whether being developed or not).

We already have a mechanism to charge development for infrastructure needs - the Development Contribution.

Take heritage overlays for example. They provide a betterment (increased amenity value afforded by the planning system) - and so a component of betterment should be calculated in the consideration of rates for all those protected by the overlay. And the opposite (lower rates) should be true when a worsenment (such as a new highway in near proximity) occurs.

Too many of the rating tools we use are fixed price per residential unit - and thus, the land value component of most rating systems has diminished significantly over time. This trend away from land value tax started with the move away from LV to CV as the basis for the general rate, and then moved even further away with the introduction of the UAGC;

https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/property-rates-valuations/your-rate…

Rates is a land value capture mechanism

An easy way would be to set the rating differentials to reflect the range/extent of activity/development allowed as a permitted or controlled activity under the zone/overlays/precincts applying to a property.

Yes, with GIS it's easy. Just bearing in mind that my point is that the land with greater development controls (meaning less ability to develop - less ability to have views affected, etc.) are the ones that would see a higher differential paid. Essentially because planning rules/laws protect the existing amenity values of those properties. A sort of NIMBY differential.

First of all, well done David Norman in writing an article on housing that talks about costs and trade-offs and who gets to use the windfall gains, but does not mention 'affordability' once. That is a special skill and takes some effort to do that.

And windfall gains, yes, but who's windfall?

At present, it's all been to the seller of the developable site and is all in the land value.

What makes the council think they can have access to this, or just tack it on as a fee, other than charge what is the true cost of providing infrastructure?

Once again, prices go up, and housing quality goes down. Are the trade-offs worth it?

Just increase rates appropriately to pay for infrastructure maintenance and growth. Preferably levied against land values only for incentive purposes. Currently Auckland council generates about one third of it's income from property rates. So much has been stacked on the cost of development and new builds. Rates should cover all of the infrastructure and maintenance, then maybe we'd have affordable housing which would be more of a utility than a money printing tree for the rich.

Sorry, why should ratepayers pay through the nose when central government keeps opening the flood-gates for migration without the financial assistance to help support it?

Benefitting from the value increases, benefit from the corollaries. Can't have one without the other.

There's no true benefit from valuation increases because it's still the same house. If you sell & buy another, both valuations will also reflect that money is simply the medium of exchange.

But properties certainly gain betterment financially from the city around them. Fair enough to recapture some of that. Has to be funded somehow and places benefiting the most can return the betterment at the same percentage rate that places benefiting less do. Pretty fair, and provides other benefits such as encouraging good use of the land.

Council with it's hand out for money once again. They are rapacious.

Higher development potential, equals higher rates. It has always been this way to promote/force landbankers to move on and allow development to progress.

While the intent of the legislation make sence (more in the middle), but could decimate heritage areas and streets. Hopefully its I.plementation can be moderated. One also notes that without billions being spent on much larger poop, water, and electrical infrastructure, much of central Auckland cannot be upsized anyway.

Would add that smart money was buying future upsize zoning when the draft super city plan came out. Those buying now are a bit late and will have to wait ten years or pay tax.

Indeed, has been that way since NZ first put in land tax in the 1890s.

"Heritage" areas is a bit of an exaggeration in NZ though. Not every drafty old house is special, and very few in Auckland are of any particular note.

Better to allow more freedom for people to use their land.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.