At a glance

The infrastructure shortfall is massive across practically every category. The cost of delivering this infrastructure will overwhelmingly be borne by taxpayers, ratepayers and utilities customers. Third-party funding of infrastructure, while no silver bullet, provides access to funds and skills now, frees Government to focus on service delivery, and includes well-known tools to bridge the gap.

We discuss these key points in Part I. Part II of this series will evaluate the third-party funding tools available, discuss sectors where they are already in play, and set out the main opportunities for New Zealand to apply third-party funding.

Tell me where it hurts

Ever since I began my economics career 17 years ago, and probably for years before, New Zealanders bemoaned the lack of investment in, and maintenance of, infrastructure. Over successive governments, that reality has worsened.

At the same time, public expectations of an acceptable level of service have grown, and central government policy has mandated dramatically improved standards for infrastructure. Add these changes to historically inadequate provision for depreciation of existing assets and cost escalation in the sector pre-dating but exacerbated by disrupted supply chains and closed borders. It should be no surprise that we have reached this juncture.

Whatever one’s thoughts on the water reforms proposed by the previous government, it was helpful to have a starting point for what water improvements over the next 30 or 40 years may cost - $120 to $185 billion was the range provided1. That is more detail than has been provided for some of the other areas desperately in need of new or remediated infrastructure albeit limited assessments have been completed for some of them. As regional councils interpret what the National Policy Statement on Freshwater Management means for, say, wastewater treatment plant standards, local government is being confronted with costs many had never dreamed may be required as they head into the next Long-Term Plan (10-year budget) process.

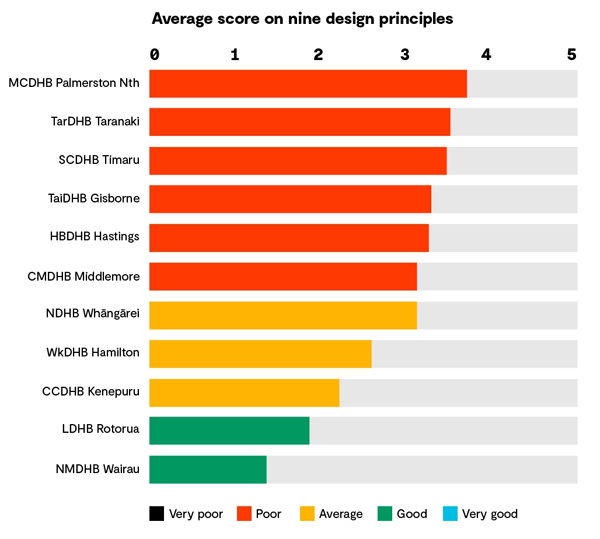

Work done on what fit-for-purpose buildings and other healthcare infrastructure would cost over the next 10 years equates to a cost of $17 billion in 2023 dollars2. With only one major hospital upgrade (Dunedin) announced in the last decade and that one set to be completed in only 2028, New Zealand’s hospitals generally range in age from 30 to over 50 years. Better infrastructure won’t single-handedly solve the healthcare crisis New Zealand faces, but it will certainly help. When some hospitals routinely have buckets catching rainwater, and black mold growing on the walls, it’s well past time for upgrades or even rebuilds3.

Figure 1: Emergency rooms that are not fit for purpose (4)

The main source of funding for land transport – the National Land Transport Fund – simply cannot keep up with the ever-growing number of roading, public transport and cycleway projects it needs to maintain, let alone growth. Over $4 billion was spent each year on transport average between 2011 and 2021, but this was not enough5. Add in cyclone and flood recovery in the Hawkes Bay and Auckland, and the scale of the transport challenge becomes apparent.

As New Zealand aims to electrify to cut emissions and boost its green credentials, an estimated increase in electricity capacity of 170% is required over 30 years6. Costing this is hard, but using recent examples of renewable energy project costs, this could be over $50 billion.

There is still a housing shortfall of perhaps 20,000 dwellings (down from over 40,000) across New Zealand. With less residential development as interest rates have surged, reducing land values, net migration has hit record levels, with a net gain of 110,000 in the last 12 months. Consequently, the shortage is growing by around 5,000 a year. And arguably New Zealand needs to build many more houses than the nominal shortfall. A poor quality housing stock that makes many residents ill carries all sorts of other social costs for the country that could be prevented if everyone lived in warm, dry, safe homes7.

Then there is tourism infrastructure, already bursting at the seams pre-COVID, with very little new investment during the three years of COVID isolation. Auckland still does not have a solution for mooring larger cruise ships downtown after the mooring dolphin proposal was passed and then abandoned, let alone an adequate cruise ship terminal, a nationwide challenge8. Conference centres have opened in Christchurch and Wellington, but there is a significant gap in second-tier cities. There is a need for more public toilets, airport upgrades, and adequate infrastructure along our great walks and in freedom camping areas.

Pulling off the band aid sooner rather than later

There are no silver bullets for overcoming this shortfall. While there are a number of funding options available, including third party upfront funding, the cost of infrastructure will always be overwhelmingly be borne by taxpayers, ratepayers, or users of the infrastructure. These three groups are in most cases the same people.

At the edges, there will always be some cross-subsidy. Larger urban centres in New Zealand tend to have higher incomes and consequently higher tax takes, but a lower-per-capita spend on things like highway lanes than further-flung areas with low population densities. And so urban centres generally help fund services in more remote areas. This pattern will likely continue via the tax system, even as urban centres seek the funding they need for their own infrastructure shortfalls.

But on these small islands with our handful of people, we have been living beyond our means for decades, not putting aside enough for the rainy day of infrastructure replacement, improvement or growth. It is now bucketing down, and feeling around for coins under the couch we’ve come up empty-handed. To have the infrastructure we need, while balancing environmental and social considerations, we are going to feel a bit poorer when it comes to the nice-to-haves. It is inescapable.

The right salve?

If it is true that there’s no such thing as a free lunch – that New Zealand’s taxpayers, ratepayers or utilities customers will ultimately be the ones paying for bulk of the much-needed infrastructure – is there any benefit to getting third-parties involved to fund infrastructure?

Before answering, it’s worth first explaining what we mean by third-party funding, and second, why we’re discussing it at all.

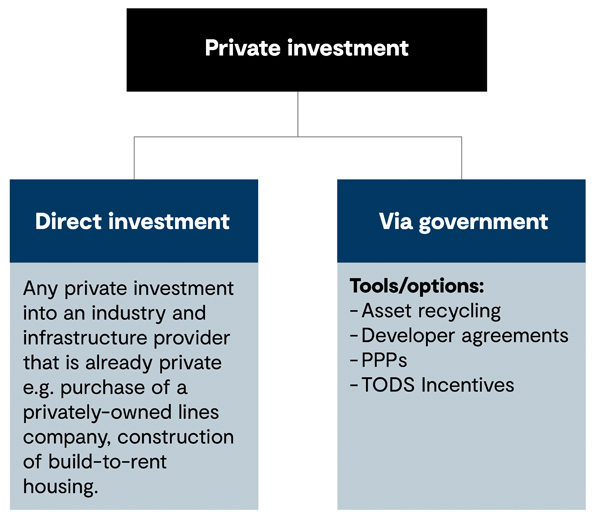

By third-party funding we mean any funding from a source other than a New Zealand government, local government or affiliated agency. It could include our own NZ Super Fund, overseas investment firms, and specialist infrastructure developers and operators. It can even, notwithstanding geopolitical considerations, include overseas governments or sovereign wealth funds.

This third-party funding can be of various kinds, ranging from direct purchase or capacity-adding, to public-private partnerships (PPPs), transit-oriented development (TODs), incentives, developer agreements or asset purchases where money is recycled back into infrastructure. We will explore these investment types in more detail in Part II of this series.

We raise this now as the incoming National Party-led government has clearly expressed a desire to source third-party funding to sate the infrastructure pain, a departure from the previous government.

But is there any validity to this approach? Yes, for several reasons:

- It accesses funds for councils and central government agencies with maxed-out debt: Third-party funding, especially if there is a way for it to be paid for by users of the service directly, or if it can be accommodated by non-monetary (i.e. tax) incentives, provides an alternative to keep debt off a government entity’s balance sheet. An example of this approach could be providing additional development options for an investor who agrees to build a mass rapid transit route (a TOD/incentive amalgam). This latter instance is probably the closest we could get to “cost-less” delivery of infrastructure.

- It accesses skills and expertise. New Zealand is small. How many multi-kilometre tunnels do we bore each year? How many wastewater treatment plants do we build? A willingness to countenance third-party funding opens access to knowledge and experience from those who do this day-in and day-out.

- Owning buildings is not Government’s business. Delivering services is. Many economists would argue that most services can and should be delivered by the private sector. For better or worse, here in New Zealand we have a social contract that today agrees that by and large, things like healthcare and education should be delivered by the state. But nowhere in the social contract is there an expectation that the state should own the hospital building or even the school. Let government focus on delivering surgeries, emergency care and rocket scientists. Let third-parties change the lightbulbs and water the rugby fields.

- We’ve done this before and it has worked. Many of the approaches set out briefly above have been used in New Zealand. In some ways, we are looking back to move forward. And in a global sense, none of these approaches is revolutionary. Each tool has its strengths and weaknesses (a fact we discuss in Part II). None of them are perfect, but they give us options.

- The money is there. Even with interest rates rising sharply across the world, there is plenty of funding available for infrastructure investment globally. GHD works with many of these

Beware the side-effects

As with any funding tool, third-party funding has its strengths and weaknesses. Its detractors mount good arguments in certain circumstances, and opportunities, while many, are not abundant across all infrastructure categories, points we will examine in Part II of this series.

But what we do know is this: we simply cannot continue to let our infrastructure shortfall go untreated the way we have for decades. That would be terminal.

References

1 Department of Internal Affairs (2021). Water services reform: national evidence base

2 Ministry of Health. 2020. The National Asset Management Programme for district health boards. Report 1: The current-state assessment

3 See here for instance

4 Ministry of Health. 2020. The National Asset Management Programme for district health boards. Report 1: The current-state assessment

5 Waka Kotahi. Funding and transport – dashboard and open data

6 New Zealand’s first Infrastructure Strategy sets a path for a thriving Aotearoa | News | Te Waihanga

7 See here for instance

8 See here for instance

David Norman is Chief Economist Australia and New Zealand, at GHD. You can contact him here.

17 Comments

NZ has its own currency the NZ Dollar and which is itself a public utility and which can then finance anything we decide to spend it on. What we don't have though are unlimited resources with which this money can employ and that is the real issue and no amount of alternative funding models can alter that fact.

This opinion piece seems very pro privitisation. Sure the state can operate a hospital, but is renting the building off a third party the best way, long term? As a society / nation we would be better served by getting politicians who think beyond the three year election horizon and by hardening up and committing to some long term spending to prepare for the future.

We seemed to be able to do this in the 50s and 60s, so why not now.

This piece was written BY A PERSON TRAINED IN ECONOMICS!!!!!

Forget pro-privatisation; this person is energy-blind. And resource-blind, I suspect. But thinks he can comment re physical infrastructure because he's not money-blind. Go figure.

'To have the infrastructure we need, while balancing environmental and' sorry, it's nothing like that. It's a case of the finite resources of a finite planet (NNRs, Renewables, and Sinks) and the amounts left and the rates of consumption.

They teach economics as if we had an infinite planet - so growth is forever possible, anthropocentric arrogance accommodatable. Climate alone tells us this is horsepoo - let alone the Great Extinction, the biomass displacement, the sperm-count losses....

Why are we still giving this kind of nonsense oxygen? Has he asked where bitumen comes from? Or what it can be replaced by? Nope; just arguing that someone else can own it. Sheeesh...

This enormous shortfall must be a direct consequence of flooding the country with immigrants. Pretty much the highest in the OECD.

Are these unemployed, barely housed, low grade immigrants going to contribute anything towards paying for this infrastructure and housing shortfall? Are they going to go anywhere near replace the economic contribution of the young Kiwis that they are chasing out of the country? We are going backwards at an alarming rate. No political parties have any plausible plan to deal with the issue. Shear stupidly all round. There is no hope remaking in this country which is rushing headlong into becoming a South Pacific banana republic.

Yep, I explain our infrastructure problem to students in three simple charts:

1. Total NZ Infrastructure Investment per % GDP

2. Public Investment Share of GDP (both central and local government)

3. NZ Resident Population

Pictures tell a thousand words.

The interest required from private debt and equity is over two times that of government bonds.

The present value difference is even larger.

The arguments for why one would use private debt is based on risk transfer to the ppp structure, and efficiencies.

Risk can also be transferred to Alliances and other non ppp structures. And efficiencies are hard to find in any of the Australasian examples of completed projects.

Those lobbying for ppps are usually those who clip the ticket. Or politicians who think they can get a free lunch and are convinced by the PowerPoint slides from the good ol boys.

Yes, a great example would be to sell the Auckland Harbour Bridge to a private equity firm/fund :-).

My understanding is that the institution of the corporation came about to enable many to pay a litte to establish vital infrastructure (water reticulation, sewerage, roads, hospitals, electricity generation and distribution) that all would benefit from. There was no profit driver in there.

That has all changed in the last 40 years.

Rather than outside investment to maintain and develop basic infrastructure (I don't count catering for tourism in that category), bring in outside investment for the nice to have developments such as conference centres.

For the basic infrastructure (hospitals, roading, waste water, schools) bring back the Ministry of works - profit driven models begone.

We gear our country for property gains then we cry when we dont have any infrastructure. I have two friends that are doctors quite young. Both are packing bags and moving to Auz next month as they dont want to pay 1 million for a $hit box. Think about that. The only way out of this mess is to stop investment in housing and put it into wealth producing infrastructure or assets. Its so simple im often surprised about why we cant do this as a country..... easily solved with the right policy.

I have a friend who's kid is 3rd yr med. He, and his classmates are all planning on moving to Aussie post graduation. They will go straight to the equivalent salary of the highest pay grade specialist in NZ, whic normally takes another fifteen years of training an time. A no brainer really from their perspective.

Reality here is if we don't start bonding entry to med school there wont be any junior doctors.

While I can be as sceptical as other commenters here, nevertheless, thanks for bringing the scale of the issue to the foreground.

My comment is about the governance failure about this failure to disclose.

Is it the people / system we elect to do this governance role? Or is it our civil service? Who should have been talking about this? Who owns this problem?

Currently, perhaps it is no one's responsibility to tell the emperor he has no clothes?

Should we have someone on the bridge of the our ship on lookout duty? Should we have someone on shore whose task is thinking about the best route for our ship?

If truly no one currently owns this problem, what changes do we need to make to our constitution and our systems to get this?

If we don't do this right, we are guaranteed another fine mess. I define it as madness to using the same methods to solve the problem as got us in the problem.

Let's first debate and solve the fundamental issue. It is not the infrastructure funding shortfall. It is the system that has allowed this. Then I think we can decide how to fund the problem.

yes, the System is the problem

But why do you then mention 'funding'?

Maybe you need to understand Systems?

I clarify:. The article indentifies funding as very important. Certainly the numbers are big. Even though these numbers are big, before we engage with the how question (funding), I think we should engage with why, what, when and who.

I am not stroking your ego, but I actually I regard your constant reminders about the closed system we appear to live in, as valuable. As a former farmer, I understand closed systems and system limits.

I do admit slaving to obtain a pass in economics, but soon learned the shortcomings of the dismal science trading cattle.

It seems my brain is focused on "floundering about" , using my lifetime experience, with the question, is there a better way to collectively make decisions, and obtain from the population informed consent? Does it all come down to some kind of coin toss? Is there a better idea than that?

The issue being twofold: the lack of understanding and engagement in local government. Everyone wants the best of everything but they dont wish to pay for it. Also local government putting off key infrastructure as it is physical and often longstanding assets that can be left to make the budgets look better for other things.

Unfortunately everyone meeds to learn that because of these factors, funds have been misspent and key spending deferred and the catchup will be significant. We cant have the best of everything and get it all for free.

The problem is straightforward and simple.

Successive governments:

a) running immigration rates well beyond sustainable levels pushing up infrastructure demand.

b) failure to regulate local government to force it to spend on asset maintenance and renewals ahead of other expenditure and to fund depreciation fully.

c) running a neoliberal tax system that lacks capital gains taxes, and inheritance/death taxes so we are underfunded in the first place.

NZ needs to wake up. We cannot afford to pay for the massive infrastructure deficit we have. We are now a poor country due to the failures of one government after another.

I agree. So it is a system problem? Yes? Doesn't matter who we have managing it, it will always operate, except by random chance, to produce sub optimal solutions? Isn't that what the last 50 years history shows us?

So what shall we do collectively? Change something, or persist?

There is a problem with how central government 'views' depreciation in local government accounting, and how local government actually treats/uses depreciation. Central government 'views' depreciation as an asset replacement funding mechanism, whereas that is not how LGs use monies raised to fund depreciation. The below is LGNZ's submission to the Productivity Commission's response to their inquiry on LG funding:

An important outcome of this review could be to provide clarity on how “depreciation” should be approached. On this point, LGNZ has questions about the depreciation discussion in box 3 on pages 22 and 23. This section makes reference to “providing funds for future renewals” and the amount of depreciation over time having “accumulated” to roughly equal the total cost of replacing a council’s assets. In LGNZ’s view, the latter comment, in particular, is simply wrong if it implies the creation of a “replacement fund”. While councils may choose to build up reserve funds for specific purposes, depreciation does not require them to accumulate a replacement fund.

An optimal approach to investing in long life infrastructure that meets inter-generational objectives would be to raise the initial capital cost through some form of long term borrowing and pay it off over the life of the asset. Consequently, depreciation is the operational cost of renewals and maintenance to preserve levels of service.

LOL - "councils may choose to build up reserve funds" - it doesn't happen in my experience. Look at any LG (District/City Council) budget or annual report - and add up the costs for depreciation and interest. This is the lion's share of where LG revenue is spent - and (effectively) ratepayers get nothing 'concrete' for it.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.