The Australian Labor Party under Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has won a second term in government. And won it convincingly.

The votes are still being counted but it appears Labor will have at least 90 seats in the 150-seat House of Representatives. That’s a gain of more than 14 seats. Labor’s opposition, a coalition of the Liberal Party and the National Party, looks set to lose at least 10 seats and end up with just half the number of MPs that Labor will have.

Independent candidates, including the so-called Teal candidates, held on to their seats and may pick up one or two more.

The election is a triumph for PM Albanese and a catastrophe for the opposition leader Peter Dutton. To add insult to injury Dutton lost the seat of Dickson in Queensland that he had held for 24 years.

At the beginning of the year Labor trailed the opposition Coalition in most of the polls. Voters were angry about the dual crises of housing and the cost of living, and Labor was still smarting from its unsuccessful promotion of a referendum on an Indigenous Voice to parliament. How then did the Labor government achieve such a stunning election victory?

The easy answer is the Coalition ran a terrible election campaign. But there’s more to it than that. The scale of the Coalition’s loss reflects a deeper problem, namely a growing disconnect between the Liberal Party arm of the Coalition and large parts of its erstwhile voting base.

John Howard, a former Liberal Party Prime Minister and one of Australia’s canniest politicians, recognised that the success of the Liberal Party depended on being what he called a ‘broad church’ i.e. a party with wide electoral appeal. That broad church encompassed both conservative voters and small ‘l’ liberal voters.

Australian politics, and this week’s election in particular, indicate that it’s now increasingly difficult for one party to win over both those constituencies. They have very different, and often irreconcilable, views on issues like climate change, the environment, indigenous affairs, and anything to do with the ‘culture wars’.

Inner-city and suburban voters in Australia, particularly women and young people, have become more progressive over recent elections. However, the Liberal Party has not. The result has been a leakage of votes to the Greens, to Labor, and especially to Teal independents.

The latter are progressive on social and cultural issues but centrist on economic issues. That ‘green and blue’ combination is attractive to many Australians who reject the conservatism of the Liberal Party but view Labor and the Greens as too left-wing on economic issues.

Despite its continental size, Australia is one of the most urbanised countries in the world with the majority of people living in the capital cities. That spells disaster for a party struggling with inner-city and suburban voters.

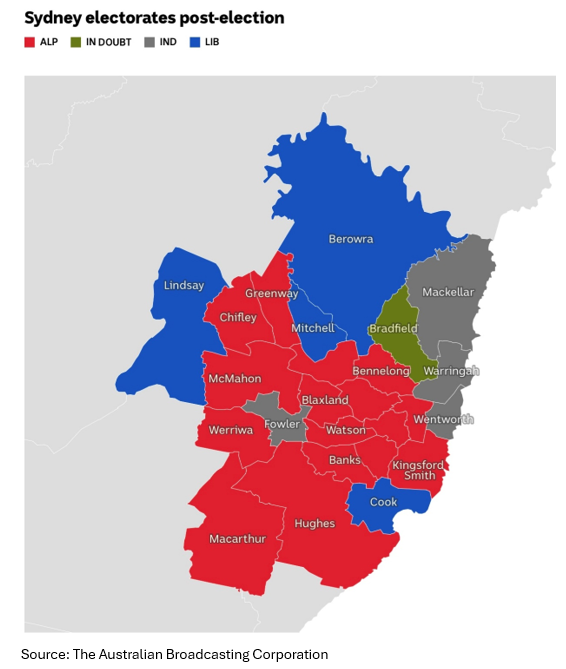

Nothing illustrates the Liberal Party’s dilemma better than Sydney. Current projections indicate the Liberals will win just four of the city’s 20 seats.

The picture is similar in Melbourne.

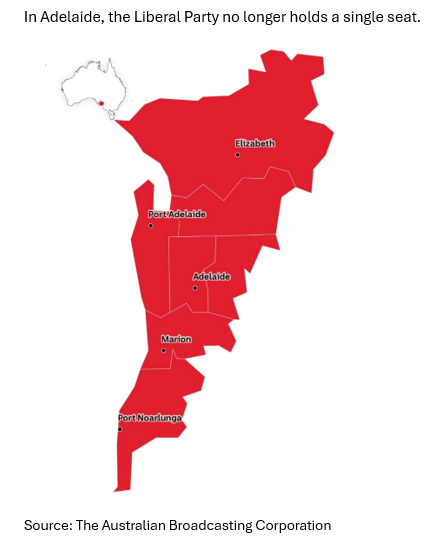

In Adelaide, the Liberal Party no longer holds a single seat.

There’s no path to victory for a party that can’t compete in Australia’s cities.

The Liberal Party’s predicament has been exacerbated by the latest electoral wipeout. Many of the few moderate MPs remaining from its previous election defeat have now lost their seats. That means the conservatives will have an even tighter grip on the party going forward.

Significantly, that conservatism is focused on climate change, immigration, national security, and cultural issues rather than the economy. The Liberal Party no longer practices ‘classical liberalism’. Despite some of its rhetoric, it’s not a proponent of small government and low taxes. Indeed, its spending promises in the election campaign exceeded those of the profligate Labor Party.

The nature of the Liberal Party’s conservatism leads inevitably to discussion of the elephant in the electoral room – Donald Trump. There are certainly similarities in that both appeal to rural and regional rather than urban voters. They also both do better with older voters and share an element of nationalist populism. However, that’s more a case of Peter Dutton pursuing a conservatism he believes in than Dutton just copying Donald Trump.

There’s no doubt the US president had some impact on the latest Australian election, although comparisons with the Canadian election are not useful. Trump has not proposed annexing Australia. Yet.

The president’s primary influence on the Australian election was the economic and geopolitical uncertainty he’s created worldwide in his first 100 days. Uncertainty tends to aid incumbent governments as many voters stick with the devil they know rather than risk an unknown quantity.

That definitely helped the incumbent Labor government of Anthony Albanese. However, the scale of his landslide can’t be explained by uncertainty alone. Domestic politics were the key and specifically the widening ideological gap between the Liberal Party and an increasing number of Australian voters.

There’s an issue here for New Zealand’s National Party. Traditionally a ‘broad church’ center-right party similar to Australia’s Liberal Party, National faces the same task of managing the often-conflicting forces of liberalism and conservatism. The trick is to craft a policy platform that satisfies the liberals without offending the conservatives, and vice versa.

The last two Australian elections suggest that trick is getting harder to perform.

*Ross Stitt is a freelance writer with a PhD in political science. He is a New Zealander based in Sydney. His articles are part of our 'Understanding Australia' series.

5 Comments

I'm curious why the Teals all act as independents instead of banding together to form a team? If they're a strengthening force that's eating away at the Nat/Lib vote, wouldn't making it official help with branding or even succeeding the Liberals as the main opposition? Or does the nature of their proportional representation without coat tailing make it pointless to ally?

Part of the appeal of Teals is they are NOT a party. Voters cynical of party politics can just vote for the person they prefer without voting for a party. But of course many Teals collaborate when their interests align

A 'landslide' and a majority, based on about 35% for the electorate voting for them, and where the coalition picked up about 32%?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2025_Australian_federal_election

That all feels a bit sub-optimum in terms of representation.

...National faces the same task of managing the often-conflicting forces of liberalism and conservatism. The trick is to craft a policy platform that satisfies the liberals without offending the conservatives, and vice versa.

Not so much, we operate MMP and independents don't win seats - no equivalent of the Teals can exist.

Also, NZ has both the liberal ACT and conservative NZFirst parties to bracket the National Party. The National party stands at the centre and both of its extremes either vote for them or their allies.

I think the writer was referring to managing the forces within the National party

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.