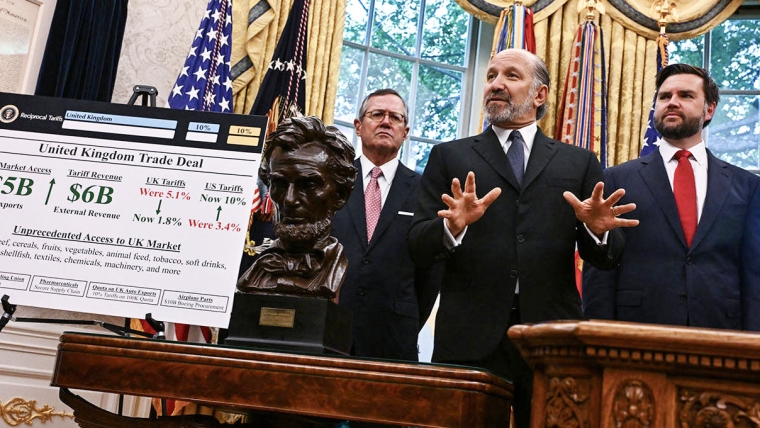

The global trade war that Donald Trump launched on April 2 has entered a new phase: dealmaking. A new memorandum of understanding with the United Kingdom lists “initial proposals” that might eventually be hammered into a “free-trade deal.” In an online post titled “art of the deal,” the White House proclaimed a 90-day suspension of the tariffs that it had unilaterally imposed on China, and an end to Chinese “retaliation.” According to the administration, negotiations are ongoing with “dozens” of other countries.

Such “deals” imply that the United States can and will enter new, binding agreements on trade with other countries. But can the US bind itself credibly anymore?

A country like the US typically makes binding international commitments through statutory legislation or treaties signed and ratified by both governments. If one side can walk away without notice from a law or treaty, its commitment is not credible. Trump’s own actions show that he does not believe himself to be bound by statute or treaty, and no one in the US legal system is willing or able to force him to abide by them in a timely and effective fashion.

Consider statutes first. Since the eighteenth century, Congress has delegated carefully designed trade authorities to the executive. Presidents George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson all had clearly defined authorisations to embargo ships. In delegating such trade authority, however, Congress also imposes limits, which means that trade partners can understand what to expect from the White House by reading the text of statutes.

The Trump administration has short-circuited statutory limits, largely skirting the laws usually relied on for trade matters, such as the 1962 Trade Expansion Act. These statutes impose time-consuming obligations to investigate and make findings before imposing tariffs. But in its impatience to make a political splash, the Trump administration used a 1977 statute, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, to try to justify its “reciprocal” tariffs.

As I and many other commentators have pointed out, this 1977 law plainly does not permit tariffs of the sort imposed on April 2. But if the tariffs on the UK and China were unlawful from day one, White House trade negotiators cannot now credibly claim to be bound by any federal statute.

What about international law? The gold standard is the treaty. But here, too, Trump has shown that he cannot and will not be bound. In 2018, his first administration insisted on renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement, and Congress ratified the resulting US-Mexico-Canada Agreement in 2020. But Trump unilaterally ditched it by imposing across-the-board 25% tariffs on both partner countries this year. He has even gone so far as to suggest that the 1908 Canada-US border treaty creates an “artificial line” that “makes no sense.” As a result, neither US statutes nor treaties provide for a credible commitment in trade policy.

A long-standing ambiguity in US law complicates the situation: Exactly how binding are international agreements supposed to be? Under the prevailing understanding of US constitutional law, Trump can withdraw from treaties without notice to international partners or Congress. The leading example is President Jimmy Carter’s 1978 decision to terminate America’s 1954 mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. US senators, led by Barry Goldwater, tried to challenge Carter’s decision in court, but they failed. The Supreme Court turned their suit aside on procedural grounds.

This commitment problem would be mitigated if there was some other actor in the US legal system that could check the president in a timely fashion. But Congress has been supine. Republican legislators are so terrified of being challenged in a party primary election that they have offered no resistance to Trump, even when confronted with manifestly unqualified nominees to fill senior positions in the executive branch.

Some hope the courts will provide a check on the administration. Just this week, the US Court of International Trade in Manhattan heard arguments in the first legal challenge to the tariffs. But I am not optimistic. Even if judges do act, the litigation process takes so long as to leave Trump with wide practical discretion to use illegal tariffs. His administration has already shown itself willing to disregard court orders in other instances, and its legal arguments for doing so would be even stronger when foreign affairs are at issue.

In short, no other country should take it for granted that Trump’s “deals” as binding or durable. They should heed a warning from the law firms that have concluded deals with Trump. Rather than finding certainty, these firms have found that the president views such arrangements as endlessly malleable. He will not hesitate to renege and impose new conditions whenever it suits him.

Of course, politically vulnerable leaders such as UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer may grasp for deals to secure temporary trade-related relief. But whatever they think they have gotten will be illusory. The very tools that Trump has used to fight his trade war make it far more difficult to reach a peace.

Aziz Huq, Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, is the author of The Collapse of Constitutional Remedies (Oxford University Press, 2021). (c) 2025 Project Syndicate. Used here with permission.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.