By Brendon Harre

Christchurch as fast as it will ever get

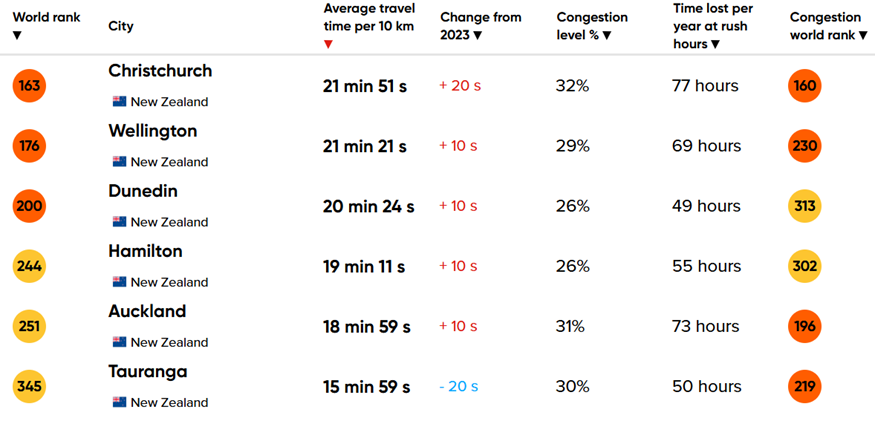

Tomtom data shows driving 10km in Christchurch is slower than New Zealand’s other main cities and that it is taking 20 seconds longer on average to travel this distance in 2024 compared to 2023 (which was 20 seconds slower than 2022).

Christchurch’s roads are getting slower, over a period of a year or two, this is relatively insignificant. Journeys are only a few seconds longer. Over five to ten years these seconds could add up to three to four minutes and the issue starts to become serious. Over twenty or thirty years if nothing is done then congestion will be devastating for Christchurch.

Ironically the reason this is happening is Christchurch has been a success. Greater Christchurch is the nation’s second largest urban agglomeration, with over ½ million people.

Canterbury the region that contains Christchurch has grown faster than the national average despite challenges like Christchurch’s 2011 earthquake. Selwyn the western district of Greater Christchurch is consistently one of the fastest growing districts in the country. Canterbury this century will be a region of over a million people and Greater Christchurch will exceed ¾ of million. Canterbury if it continues to grow at the nation’s population growth rate of 1.5% will have more than 1 million people by 2050 and over 800,000 people living in the Greater Christchurch area.

Canterbury is the nation’s second largest regional economy, having recently overtaken the Wellington region. Canterbury has New Zealand’s second largest residential and commercial construction industry. It is this industry and its ability to build quickly that has contained house and rent price increases, meaning many New Zealanders move to Christchurch to live, study, and work for housing affordability reasons. Christchurch has been so successful it has reversed New Zealand’s northward migration trend. Since the 2018 census 30,000 more people moved to the South Island from the North Island than moved north. Christchurch and Canterbury has been the main recipient.

Canterbury University with its nearly 25,000 students is New Zealand’s third largest tertiary institution (the first two are in Auckland).

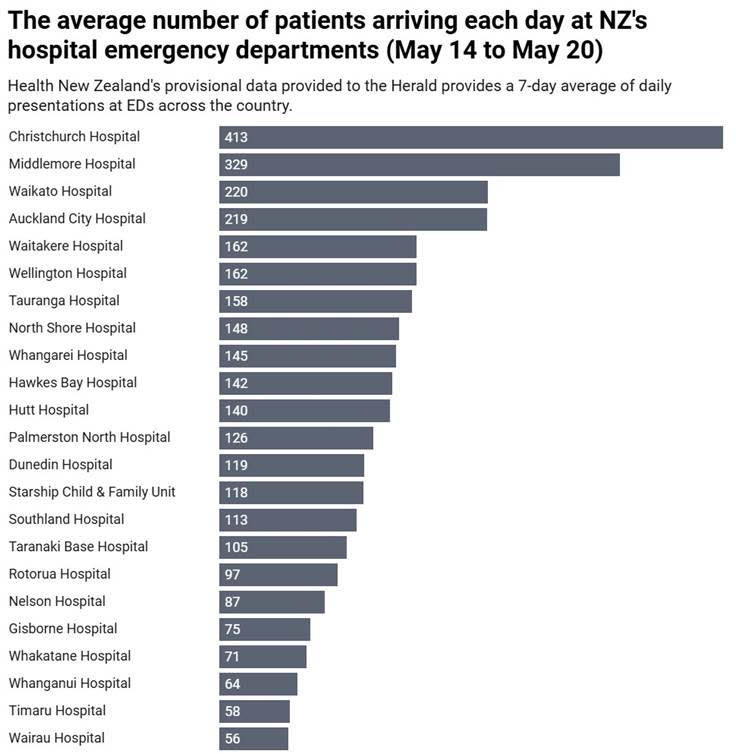

Many services in Christchurch have a scale and expertise that is not seen elsewhere in New Zealand except for Auckland. For instance, Christchurch Public Hospital is one of the busiest in the country, its ED department sees more patients in a day than any other hospital in New Zealand.

Source: Christchurch ED sees record 400-plus patients daily, raising safety concerns

Christchurch is comparable to Chicago in the sense that if you want to live, work, do business, or study in a large New Zealand city that is neither the capital city nor the nation’s largest city then Christchurch is a good option.

Chicago’s urban development has formed around a spatially planned arterial grid. Christchurch started out with a grid but then transitioned to a more ad hoc radial and dendrite pattern. Source

People who study cities agree that larger cities have greater productivity and higher incomes, because firms can take advantage of greater economies of scale, there is more innovation and knowledge spillover between firms, there is better matching between work skills and labour requirements, and there is more capacity to supply specialisation in manufacturing production, retail outlets, public and private services, and even recreational activities. Larger cities have better network effects, such as, a better online dating scene.

As cities grow, they also experience higher land rents, more crowding, worse traffic congestion, city residents are more likely to experience bad social behaviours like crime, and these residents are often subjected to poor environment characteristics like higher particulate pollution or excessive noise.

Given these positive and negative factors people and firms find their preferred place in a nation’s hierarchy of towns and cities. Typically, urban communities make up the bulk of a nation’s population. The world over is trending towards over 80% living in urban environments. For over a century this has certainly been true in New Zealand.

Urbanist evidence also indicates on average the different urban areas of a country grow at the similar rate. Greater Christchurch is likely to continue to grow at the same pace as the other fast-growing urban areas of New Zealand, which is primarily the golden triangle between Auckland, Hamilton, and Tauranga.

About 1 in 10 New Zealanders have chosen to live in Greater Christchurch because of the opportunities it provides. Going forward this ratio is likely to remain constant.

Underpinning Christchurch’s success is two important factors. It has good housing affordability relative to other New Zealand cities, and it has a city road network that has few geographic bottlenecks, meaning travelling around Christchurch historically has been relatively hassle free.

Unfortunately, the ease of city travel factor may no longer be a comparative advantage. This is not surprising. Arterial roads, intersections, and on-street parking have capacity limits. Motorways have larger limits, but even if they are free flowing, they tend to move congestion bottlenecks around a city rather than eliminate them. In any case, once road capacity and parking limits are exceeded then congestion and slower driving is the result. Christchurch like all population growth cities is experiencing a congestion headwind.

The response around the world has been to construct additional more spatially efficient transport networks that are separate to the congested road network. Mass transit in the form of subways, elevated metros, surface passenger rail, on-street light rail and BRT networks are amongst the different options. This expands capacity on a city’s most useful transport corridors. Provision for walking, cycling, and micromobility can also improve urban connectivity, as can upzoning that allows businesses, services, and higher density housing to be co-located.

Cities in general can afford to fund these upgrades when they require them because as they get larger, greater productivity, higher incomes, and higher land rents mean there are funding sources available. Congestion and parking charges can also be used as funding options. This assumes the urban agglomeration has an effective ‘collective’ organisation with the correct infrastructure funding tools so they can keep pace with their expanding population by implementing upgrades in a timely manner.

This theory of urban development is relatively straightforward. If the reader would like to dig deeper, then books like “Order without Design – How Markets Shape Cities” by Alain Bertaud and “Triumph of the City” by Edward Glaeser are great resources. Unfortunately, the practice of urban development in New Zealand’s towns and cities would be better described as complex, messy, and not straight forward.

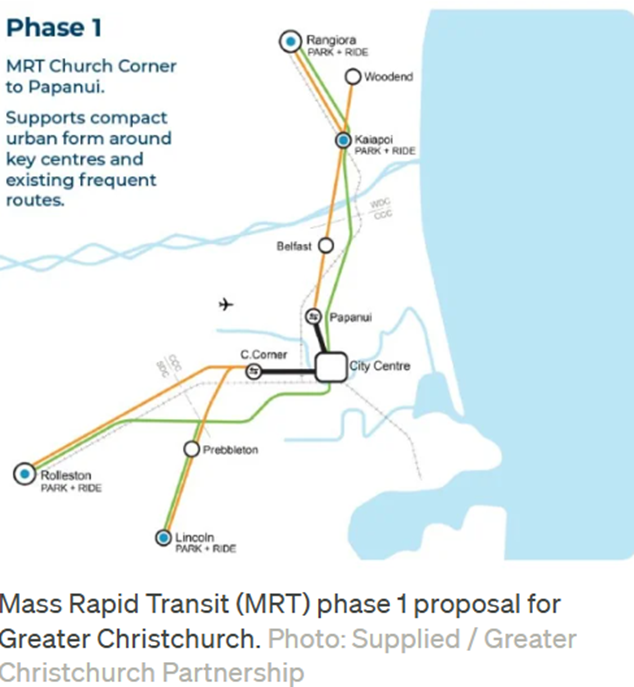

Source: Greater Christchurch councils team up for rapid public transport future

Christchurch has completed a preliminary MRT study of light rail (modern tram) that in phase one would connect Riccarton to the city centre and out to Papanui. The detailed business case is tied up in stop/start politics and currently there is no implementation timetable. The Canterbury Regional Council is looking at funding a business case for a Rolleston to Rangiora passenger rail service using the existing rail corridor.

To understand that both transit options will eventually be required it is necessary to do a deep dive into Christchurch’s history to understand the cities underlying spatial structure. An in-depth report titled Christchurch’s Transport Milestones does this work.

The summary of the report goes like this:

Christchurch was built on the Canterbury Plains separate to its port at Lyttelton which is inside an extinct volcano. The initial plan to connect the two was via coastal shipping through the Estuary and a to be constructed canal.

This changed in 1857 when the Canterbury province decided to construct the 2.6 km Lyttelton rail tunnel, a major evolution of the region’s spatial plan. The Superintendent election that year had the rail tunnel as its focus, with the pro-rail candidate William Moorhouse winning the election. The tunnel was opened in 1867 and cost £200,000, which was financed by a provincial government loan. Canterbury had only 12,000 people in 1857, so land sales emerged as the best revenue source to repay the debt.

This proved the concept that for places where people want to migrate to, adding infrastructure and amenity to land raises its commercial value. Land sales can then repay the incurred costs. In essence, this was a land value capture mechanism.

In effect, Canterbury had created an infrastructure provision model involving democratic governance, evolution of a spatial plan and an infrastructure-funding mechanism.

Approximate route of passenger rail in red. Source

Despite the provinces being abolished in 1876 (by which time Canterbury had repaid its tunnel debt) the rail spatial plan worked well for Canterbury up until the 1930s. Trams (first steam powered then electric) and cycling were added to the transport network. Urban growth in Christchurch largely followed the train and tram lines.

In the 1920s and 30s New Zealand Rail had the opportunity to modernise Christchurch rail transport network by electrifying it, like Wellington, Sydney and Melbourne did. But they chose not to. Canterbury lacked the collective organisational structure and the infrastructure funding tool to do this itself. So, as each train line reached the end of its economic life it was closed. Trams were replaced by buses, largely on the same routes. The rail and tram system that fed each other for the preceding half century began to break down. Because of decisions made in Wellington Christchurch put all its transport eggs in the road dependency basket.

The Main Highways Act of 1924 gave control to central government of roughly 10,000 km of roads designated as main highways. Petrol taxes, car registration fees, and mileage charges initially covered half the costs of the designated highways. While local ratepayers (property taxes) funded 100% of the local road network and half the highway costs. In the following decades in a couple of steps this switched to greater centralisation of control to the point that fuel taxes and road user charges went into a fund that paid for 100% of operating and capital cost of the highway network and roughly 50% of local road costs. More recently the central government transport fund has needed to be topped up from general taxes.

The names of the component parts of the road network infrastructure funding model have been renamed several times. The fund is now called the National Land Transport Fund (NLTF) and the main builder and repairer of the state highways is called the New Zealand Transport Authority (NZTA) or Waka Kotahi.

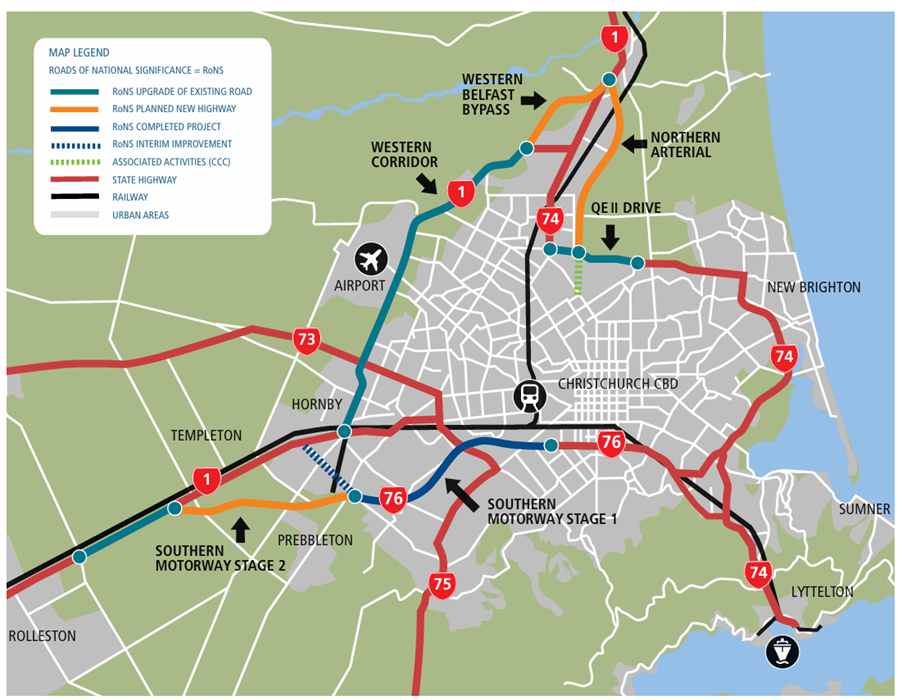

In the century since the Main Highways Act was passed Greater Christchurch has received various state highway upgrades and a new road tunnel to Lyttelton.

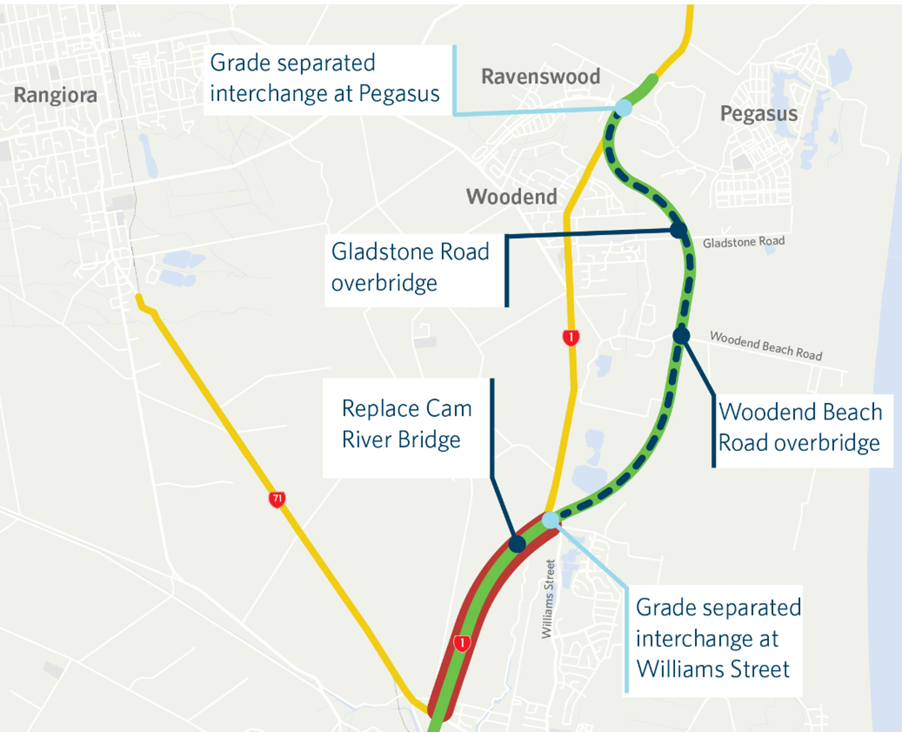

The only major future NZTA project in Greater Christchurch is to extend the northern motorway to bypass around Woodend.

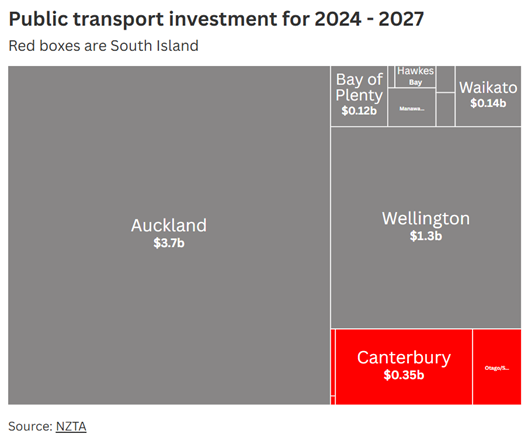

Charlie Mitchell a journalist in a series of charts details how Canterbury’s transport needs are being ignored by central government agencies.

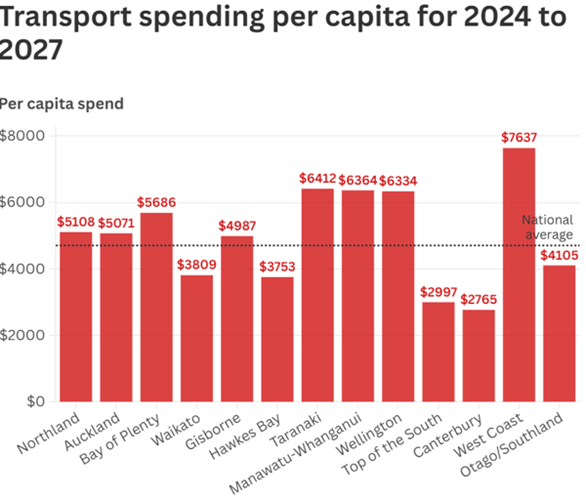

“Canterbury will get the least per capita funding of the 13 regions over the next three years, and the South Island collectively will get 36% less funding per capita than the North Island.”

Note the top of the South Island and Canterbury also received the least funding in the 2021 to 2024 period, too.

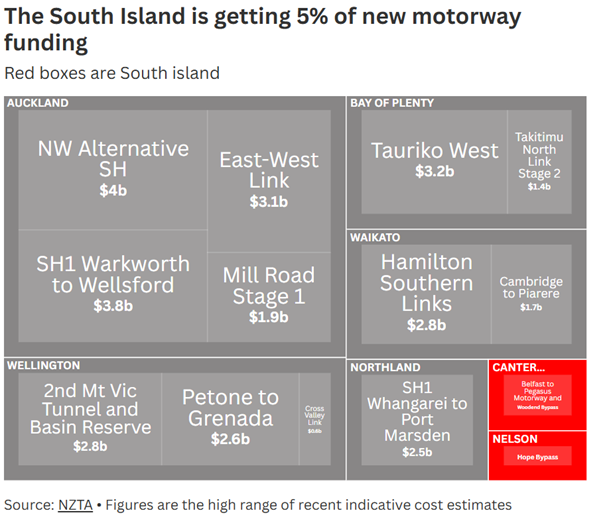

“These figures translate to the South Island, a quarter of the population, receiving about 5% of the major road infrastructure.”

“This isn’t about pitting regions against each other; all have genuine transport needs. It is to highlight the absurdity of a Government claiming to prioritise economic growth while behaving as if its second-largest economy is invisible, obscured by some mysterious fog.”

Canterbury’s transport history shows the state highway era, and its associated funding model hasn’t been good for Christchurch.

Charlie Mitchel notes in his Highway Robbery article that “If funding had matched its population share since 2021, Canterbury would have an additional $2.6b — enough for several motorways, a decade of local road maintenance, or most of a mass rapid transport (MRT) system.”

Charlie is not wrong to call Canterbury’s and the South Island transport funding “highway robbery”. In effect governments of both persuasions every three years have taken about $1500 from me and other South Islanders to give to another island which we may never visit (I have no plans on visiting the North Island in the coming years).

If the Canterbury and South Island fuel taxes and road user charges had been spent on Canterbury and the South Island, then I might receive some benefit. For example, my commute to work might be cheaper, faster, and more convenient. Also freight and business work, such as tradies going about their jobs, might travel more freely, meaning the costs of goods and services that I buy could be lower. This ‘highway robbery’ is one of the reasons I have such little respect for Wellington politicians – they legalise theft and then shrug their shoulders when challenged about it. At best I judge them to be unserious in what they do.

As much as I hate theft from me personally, there is a collective problem as well. The lack of transport investment in Greater Christchurch raises the issue of how sustainable population growth is for the city. If transport spending doesn’t keep up with population growth, then that growth will at some point hit a wall. Christchurch will no longer be a success story. Congestion and slower roads will not stop growth this year or next but eventually it will. That is the lesson from Auckland, which under invested in its city building infrastructure in the post war decades causing its current infrastructure deficit, a housing crisis, and contributed to the productivity crisis. Repeating the same mistake in Christchurch would be folly.

If New Zealand cannot address congestion in its second largest city this raises several questions.

- The social license of the NLTF/ NZTA transport funding model.

- The social license of accepting large scale immigration into New Zealand. Would a populist anti-immigration approach be better?

- The social license of liberals and progressives supporting growth. Would it be better if New Zealand accepted a degrowth mindset.

- There is also the question of how to maintain and improve infrastructure when the government’s budget is under pressure from an aging population. If effective infrastructure funding tools are not created, a downward spiral of insufficient infrastructure provision, aging population/ more outward migration and less inward immigration, leading to a decline in economic activity which causes further reductions in infrastructure provision, could easily be New Zealand’s future.

This is a lot of pressure on the government’s Chris Bishop infrastructure funding review. He is bullishly optimistic that he can achieve success. Beehive announcements such as, Investing in infrastructure for all New Zealanders | Beehive.govt.nz are very positive. The Christchurch congestion challenge will be a test case on whether his deeds match his words.

Christchurch’s mass-transit future: How long will the city wait and what will it look like?

Christchurch is the largest city in Australia or New Zealand without a mass transit system. A critical question is how long the city will wait for a modern transit system.

Christchurch is experiencing congestion. Currently the time to travel 10km through the city is increasing by 20 seconds a year. In five to ten years’ time this will be a serious problem that should have a planned remedy. If it is not fixed for twenty or thirty years, then this is the sort of problem that will be devastating to the continued success of the city.

The solution to road congestion is nothing extreme like a campaign hating motor vehicles. The solution is to give people better choices than driving. If some people can use alternative higher capacity transport options, then those people who must drive will face less crowded roads.

Not many people are aware of Christchurch’s multi-modal transport past, but a historical deep dive shows the structural bones of the city was built around street running trams integrated with the city’s main rail corridors. Even to this day many workplaces, schools and other significant destinations are near this rail corridor. I think the underlying structural bones of the city is a good indicator of what form its future transit system should take.

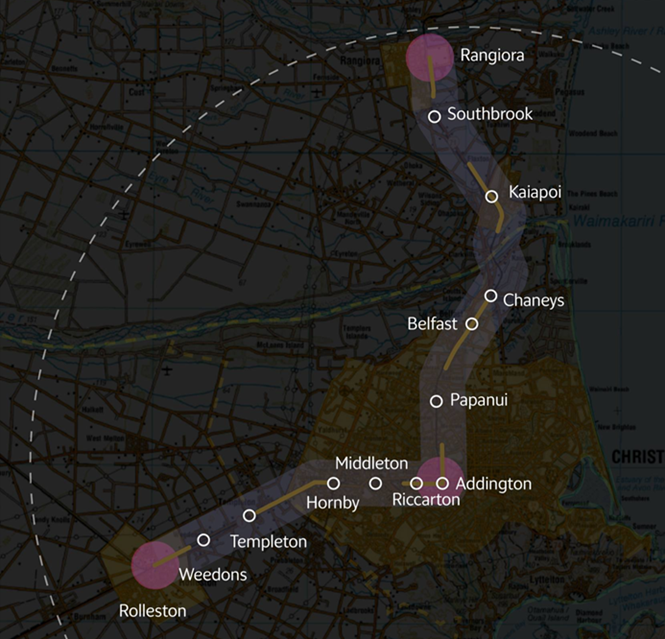

Recently Environment Canterbury (ECan) voted to approach KiwiRail to assist in preparing a business case for a Rangiora to Rolleston passenger rail service.

Councillor Joe Davies moved the motion, which was passed unanimously by councillors. He said a Rangiora to Rolleston service would be ‘‘an easy win’’, compared to the proposed mass rapid transit rail service in Christchurch, as the infrastructure is already in place. ‘‘We can’t wait 20 or 30 years; we need it in five to 10 years. ‘‘There’s a corridor already in place so there would be significantly lower set up costs compared to the mass rapid transit proposal, and this is an opportunity to link Rangiora and Rolleston to the city.’’

The proposed route covers 54.7km and links Rolleston and Rangiora with central Christchurch and serves 13 stations.

John MacDonald from Canterbury Newstalk ZB had a supportive take on the Rolleston to Rangiora rail proposal, saying.

ECAN is showing that it’s thinking about the future, which is exactly the kind of thing I want to see not just from ECAN, but all our councils.

Tell that to Waimakariri MP Matt Doocey, though.

He’s saying today: ‘Rather than coming up with pie in the sky motions, ECAN should focus on reducing rates which have rapidly increased - putting more pressure on ratepayers in a cost-of-living crisis.’’

Compare that to the likes of ECAN councillor Joe Davies who is saying we can’t wait 20 or 30 years, and we need a solution in the next five to ten years.

He says: ‘There’s a corridor already in place so there would be significantly lower set-up costs, and this is an opportunity to link Rangiora and Rolleston to the city.’’

So, he sees opportunity. Matt Doocey sees obstacles.

ECAN sees opportunity and is doing something about it, which is the approach I want to see a lot more of from our local councils.

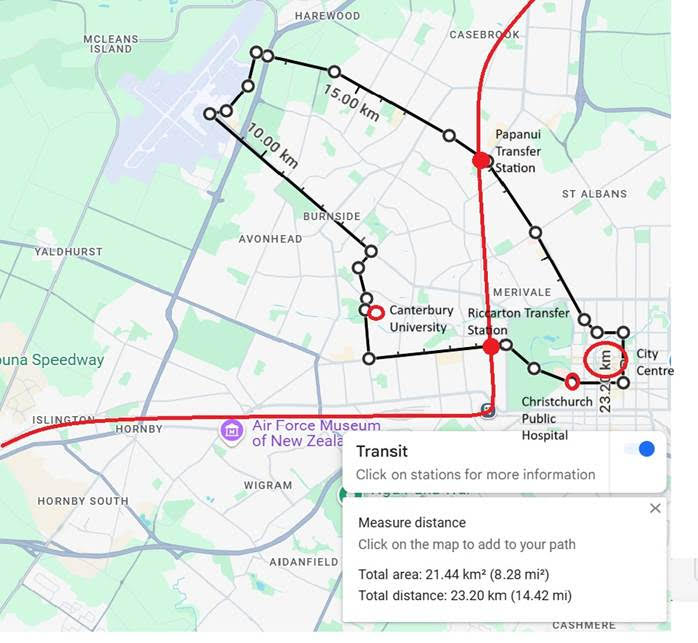

Unfortunately, not all of Christchurch’s significant destinations are near the Rolleston to Rangiora rail corridor. The university with its 25,000 students is not on the corridor, neither is the main hospital which is the largest employer in Canterbury and nor is the city centre itself. So, ultimately it will make sense to connect those significant destinations using an integrated tram and train network like the city has done in the past. Something like the light rail loop depicted below.

If the rail corridor is built first, then initially a high frequency bus service with dedicated bus lanes connecting Canterbury University with the hospital, and the city centre should be upgraded. The rail corridor would cross this route in Riccarton. There would be space between Riccarton and Kilmarnock Roads to build a transfer station. Thus, the first steps of a MRT network could be delivered relatively quickly and quite simply. When additional capacity is required then the high frequency bus services can be upgraded to light rail which can carry more passengers per vehicle. This would be like the proposed phase one of the preliminary designed MRT service, except the Riccarton end would go to the University not Church Corner.

Light rail in Christchurch when it is needed should be much less costly per kilometer to build than what was proposed in Auckland or Wellington. As it doesn’t require tunnelling, and it could be built in stages.

Eventually the light rail corridor could be expanded into a circle. The length of this proposed loop is similar to the Helsinki Light rail scheme. Which is an arc not a circle and takes about an hour to travel end to end. A Christchurch light rail loop as depicted above with vehicles travelling in both directions would mean that nowhere on the circle is further than 30 minutes away, and most destinations would be significantly less than that.

Hopefully Ecan will get commuter rail between Rolleston and Rangiora up and running in the next five to ten years. If the central government politicians in Wellington find Canterbury’s missing transport funding, then there is the money available to do it.

In the medium to long term for New Zealand cities to properly implement modern transit systems in my opinion they will require a new and better type of collective organisational structure(s) with a transit focus. This organisation(s)will need its own specific infrastructure funding tools. KiwiRail with its freight focus is not adequate. Neither is NZTA Waka Kotahi with its state highway building history and its main infrastructure funding tool being sourced from motor vehicles.

Both Auckland and Wellington have existing transit schemes yet are struggling to expand their networks. Both transit systems have quality issues, such as, a large amount of out of service delays and cancellations. So, the existing transit provision model of local councils partnering with NZTA and KiwiRail has not delivered good outcomes. Especially as it has required a series of ‘one-off’ ad hoc funding injections from central government, which itself faces in the coming decades a tightening fiscal budget due to the pressures of an aging population. New Zealand could do better.

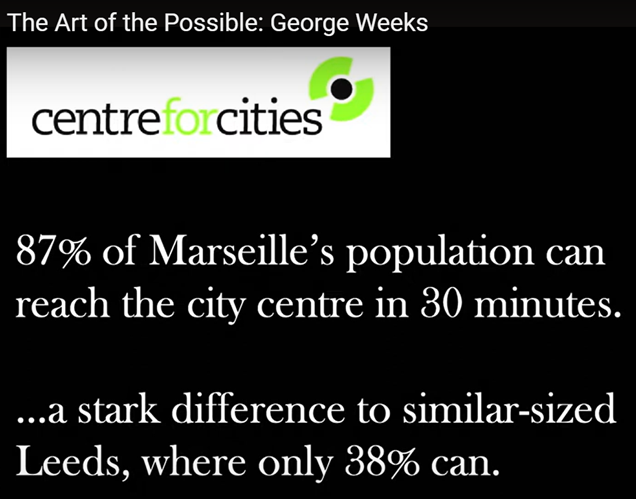

Marseille employees who work for large employers pay a 0.55% income tax to a local transport fund to get far better city access compared to Leeds residents who do not have this infrastructure funding tool. It seems like a good deal to me.

There are overseas transport funding models that New Zealand could and should copy. For instance, urban planner George Weeks, in a video titled art of the possible – shows how French cities funded the rebirth of mothballed tram services in ways that stimulated urban development and increased the number of city residents who could access significant destinations in a timely manner. This included some French cities that are much smaller than Christchurch.

This paper started out investigating why Greater Christchurch’s roads are getting slower, but it has ended up talking about Christchurch the hero. The city has faced challenges, the 2011 earthquakes, and the missing transport funding in the 2020s, have been particularly bad. Going forward if congestion is not address due to underfunding city building infrastructure this could be devastating. Yet despite these challenges 1 in 10 people have chosen to live in the city. This is not the 1 in 3 people who choose to live in Auckland or the 1 in 2 people who live north of Taupo, but 1 in 10 New Zealanders is not nothing.

In a good tale, the hero triumphs over the villain. It is my hope that Christchurch overcomes its challenges. New Zealand cannot afford for a large chunk of its population to be unsuccessful. New Zealand needs all its towns and cities to succeed.

8 Comments

Great article, Very informative - some very interesting stats in there. Highway robbery - it's a good catch phrase, but do we need to balance that lack of funding with CG funding for post-EQ facilities development. Certainly agree with you about the comparisons to Chicago. I grew up there in the suburbs and no one commuting in 5 days a week did so other than by train!

Before the motor car became so obtainable, trams, buses and trains sufficed. In those days the CBD was it, Cashel, High and Colombo Streets and adjacent. Department stores, Farmers, DIC, Beaths, Hays, Armstrongs, Drages, Drayton Jones and the only survivor Ballantynes. However the easy ability to expand the city with abundant flat land in every direction except east invited the suburbs to sprawl out and as families acquired their own vehicles more easily so it naturally did. Now apart from, work, entertainment, sport or sightseeing there is little to draw in the locals as the CBD once did. On the other hand a large number of shopping hubs have sprung up in the outer suburbs and of course there is online shopping.This situation was apparent at the time of the earthquakes. Sir Bob Jones wrote then a well constructed article pointing out the trend and why it would continue which was pointedly ignored. There was even a notion of relocating some of the University of Canterbury faculties back in the central city. However the city council commenced concocting all sorts of fancy street design and management which still exist and contribute markedly to the slow traffic flow identified in this article. In fact, on the face of it, the council, doesn’t seem to think it has introduced anywhere enough. At the end of the day it’s rather difficult to see just where the volume of daily commuters, to and from the CBD, will be drawn from. The bird has flown.

Yes, I bought a very large/extensive book which explained community input to rebuilding CHCH well before any of the plans started being put on paper/implemented. From that reading, it wasn't only Bob Jones that was ignored.

That said, I am amazed at the level of achievement (like it or not in design and concept) in rebuilding the city. Not being from there - I guess from an outsiders pov one is perhaps more impressed not knowing what else could have been.

From the beginning, I thought it really silly to attempt a rebuild of the Cathedral. I loved the Church's new cardboard cathedral - much more contemporary and practical for current needs. I felt the old Cathedral ruins should have been partially deconstructed to meet safety standards as a shell, and to be incorporated into a memorial outdoor museum-type public gathering place to record both the old and the new for generations of visitors and Cantabrians to come.

Who knows, perhaps that will be where we/it ends up anyway.

Aye the cathedral emblematically, rather sums up all the conflicting strife and poor decisions made. An opportunity to raise a symbol to Christchurch’s revitalisation wasted by vainglorious idealism, denying the realities on hand. For a start, as would be expected, it was hardly a cathedral in the grand sense of say a Salisbury or Lincoln. More like a reasonably large church in muted, modest gothic form. Renowned Christchurch architects Warren & Mahoney offered a masterful design that would have embodied a new era and remain as a commemoration, but sadly to no avail. Instead the ruins just sit there now a stark reminder daily of firstly the destruction that hit the city and secondly, the ineptitude of those who should have known better.

At last, somebody else making that suggestion about the cathedral ruin. Thank you Kate. I suggested it several times about, but too new an idea for folk to get their head around.

The fiasco remining there is a great example of local advocacy madness. Good on Nicola Willis for leaving them to wallow in it.

Yes, thanks, and the prime example was there to model such a memorial design off. They left the ruin (shell) as a memorial in Britain after Coventry Cathedral was bombed during the WWII;

https://www.coventrycathedral.org.uk/locations/the-ruins

I do like/respect the beautiful Avon River memorial site, but still think something very beautiful and moving and contemplative could have been done with Cathedral Square.

Christchurch has no geographical barriers. A flat surface. (Other than the Lyttelton hill issue, largely solved)

Queenstown on the other hand has developed appalling gridlock, and the challenge to any solution is the confines of lake, confined between steep mountains. It's squeezed.

Doppelmayer gondola systems offer a solution above the surface challenge.

Queenstown does not look like the South American cities, but has the same challenges with surface.

Was there a year ago during these winter school holidays - after not having visited for around 5 years. Oh my, the new suburban, subdivision development; the streets being dug up for upgraded infrastructure needs; and the traffic from town centre to airport...

And of course I remember it from decades ago when it was just a quaint sleepy hollow :-).

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.