US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Jared Bernstein, former President Joe Biden’s chief economist, appear to agree that US interest rates are too high. So, are we about to see a bipartisan consensus in favour of cutting them? That would be nice, but don’t get your hopes up.

Writing in The New York Times to declare himself a “budget hawk,” Bernstein has discovered a bit of math that former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard first wrote about over 40 years ago: “a government can sustain modest budget deficits so long as its economy is growing faster than the interest rate on its debt.”

I made the same point, even more strongly, for the Levy Economics Institute in 2011: “[W]here the real interest rate is below the growth rate … the sustainable deficit gets larger as the debt ‘burden’ grows. This is why big countries with big public debts can run big deficits and get away with it, as the United States has done almost without interruption since the 1930s.”

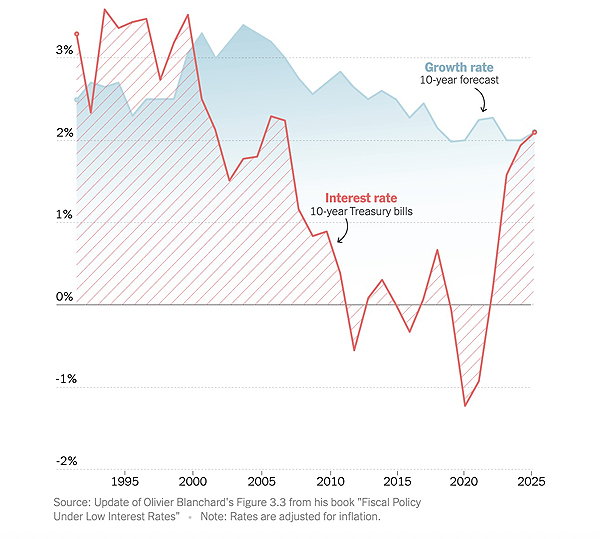

But when interest rates exceed GDP growth, the ratio of debt to GDP starts to rise. Bernstein illustrates this fear with a chart, taken from a recent Blanchard book, updated and “adjusted for inflation.”

The chart is very strange.

According to Blanchard’s chart, the sustainability problem was worst in during Bill Clinton’s presidency, a time recently celebrated in another New York Times essay by two Treasury secretaries from that period, Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers. Their time in office, they claim, “set off a virtuous economic cycle of growth, deficit reduction, lower interest rates and thus more investment and growth.” The chart claims the opposite.

And Blanchard’s sustainability index improved under George W. Bush, in the 2000s, despite tax cuts, the 2001 recession, and rising deficits, all preludes to the US subprime mortgage collapse and ensuing Global Financial Crisis of 2008, which drove deficits through the roof, but improved Blanchard’s index! If you’re beginning to doubt the practical value of this metric, you’re not alone.

Finally, “real” interest rates start to rise in 2020 – in the heart of the pandemic. But that is only because prices fell at first, with the collapse especially of oil markets in 2020. Actual interest rates did not start rising until March 2022. And why was that? Not in response to “inflation” – that was the excuse, not the cause. Interest rates rose only because the Federal Reserve decided to raise them. But the Fed plays no role in Bernstein’s analysis and is not mentioned in his column.

Summers – that other great deficit hawk – was recently in the news again, condemning the Republicans’ “Big, Beautiful Bill” and backing an analysis by the Yale Budget Lab that shows the debt-to-GDP ratio rising by 40 percentage points (relative to baseline), GDP 2.9% lower after 30 years, and the interest rate on federal debt up 0.6 percentage points – a number Bernstein calls “significant.” In fact, both the projected GDP shortfall and the interest-rate increase are trivial, and the Yale analysis shows no effect on the economy: it projects stable 2% inflation and steady full employment for decades to come. What, then, is the “burden” of all that debt?

Bessent blasted Summers for claiming that the budget bill’s cuts to Medicaid will yield thousands of premature deaths as coverage is lost, rural hospitals close, and nursing homes are squeezed. Excess deaths are indeed a plausible consequence of such cuts. But the cuts themselves are the direct result of the scaremongering over deficits and debt that is built into the budget process and the mentality of economists like Summers and now, sadly, Bernstein. It will get worse. If Medicaid and SNAP (food stamps) are expendable, who is to say that Medicare and Social Security are not?

The Yale Budget Lab does admit that “the Federal Reserve would be expected to raise interest rates” in the wake of the Republicans’ budget bill. Well, yes – and that is (again) the only reason why interest rates would rise. But the expectation might be wrong. The Fed might cut interest rates instead. If it did, the interest rate on federal debt and the debt burden might not rise. Inflation might (or might not) be a bit higher, further reducing the ratio of debt to (nominal) GDP. Investment might be a bit stronger. And, by the logic of both the Yale Budget Lab and the Congressional Budget Office, the unemployment rate would be unaffected.

Bessent is therefore correct to call out the Fed and press for lower interest rates. But, as the Fed is independent of the executive branch, his pressure may be counterproductive. Fed chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues cannot buckle without losing credibility.

A smarter move would be for Congress to move a resolution demanding lower interest rates. Congress, unlike the Treasury or the White House, does have that power, and it has, on distant occasion, threatened to use it. Now would be a good time to take that old cudgel out of the closet.

*James K. Galbraith is Chair in Government/Business Relations at the LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin and the co-author (with Jing Chen) of Entropy Economics: The Living Basis of Value and Production (University of Chicago Press, 2025). Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025, and published here with permission.

1 Comments

Are you joking? Congress uses it's power to lower interest rates?

Firstly, interest rates are not an economic recovery tool. Demand does not increase because of lower interest rates. NZ current economy is proof of that.

As the US government reduces spending over the next 12 to 18 months the US economy will contract and this contraction will increase unemployment and may help to temper inflation. What's more the tariffs are effectively a sales tax on US consumers - any gains from tax cuts are likely to be lost to tariffs.

The Fed will follow the economic conditions to set interest rates as it is proscribed to do but as a lagging indicator not a leading one.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.