Digital technology was supposed to disperse power. Early internet visionaries hoped that the revolution they were unleashing would empower individuals to free themselves from ignorance, poverty, and tyranny. And for a while, at least, it did. But today, ever-smarter algorithms increasingly predict and shape our every choice, enabling unprecedentedly effective forms of centralised, unaccountable surveillance and control.

That means the coming AI revolution may render closed political systems more stable than open ones. In an age of rapid change, transparency, pluralism, checks and balances, and other key democratic features could prove to be liabilities. Could the openness that long gave democracies their edge become the cause of their undoing?

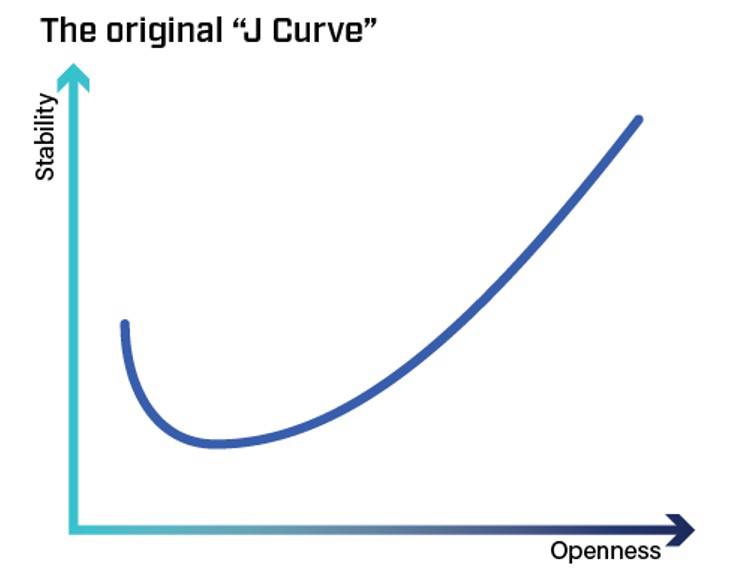

Two decades ago, I sketched a “J-curve” to illustrate the link between a country’s openness and its stability. My argument, in a nutshell, was that while mature democracies are stable because they are open, and consolidated autocracies are stable because they are closed, countries stuck in the messy middle (the nadir of the “J”) are more likely to crack under stress.

But this relationship isn’t static; it’s shaped by technology. Back then, the world was riding a wave of decentralisation. Information and communications technologies (ICT) and the internet were connecting people everywhere, arming them with more information than they had ever had access to, and tipping the scales toward citizens and open political systems. From the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union to the color revolutions in Eastern Europe and the Arab Spring in the Middle East, global liberalisation appeared inexorable.

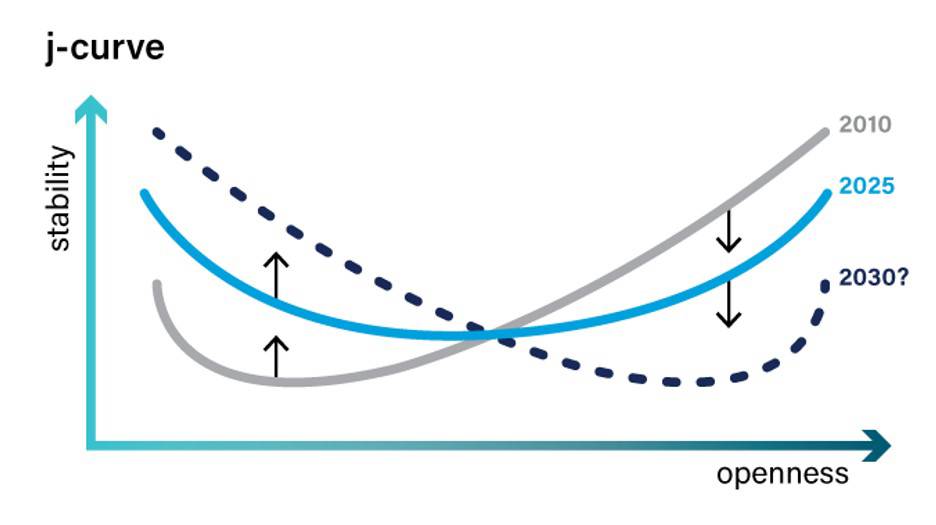

That progress has since been thrown into reverse. The decentralising ICT revolution gave way to a centralising data revolution built on network effects, digital surveillance, and algorithmic nudging. Instead of diffusing power, this technology concentrated it, handing those who control the largest datasets – be they governments or big technology companies – the ability to shape what billions of people see, do, and believe.

As citizens were turned from principal agents into objects of technological filters and data collection, closed systems gained ground. The gains made by the color revolutions and the Arab Spring were clawed back. Hungary and Turkey muzzled their free press and politicised their judiciaries. The Communist Party of China (CPC), under Xi Jinping, has consolidated power and reversed two decades of economic opening. And most dramatically, the United States has gone from being the world’s leading exporter of democracy – however inconsistently and hypocritically – to the leading exporter of the tools that undermine it.

The diffusion of AI capabilities will supercharge these trends. Models trained on our private data will soon “know” us better than we know ourselves, programming us faster than we can program them, and transferring even more power to the few who control the data and the algorithms.

Here, the J-curve warps and comes to look more like a shallow “U.” As AI spreads, both tightly closed and hyper-open societies will become relatively more fragile than they were. But over time, as the technology improves and control over the most advanced models is consolidated, AI could harden autocracies and fray democracies, flipping the shape back toward an inverted J whose stable slope now favors closed systems.

In this world, the CPC would be able to convert its vast data troves, state control of the economy, and existing surveillance apparatus into an even more potent tool of repression. The US would drift toward a more top-down, kleptocratic system in which a small club of tech titans exerts growing influence over public life in pursuit of their private interests. Both systems would become similarly centralised – and dominant – at the expense of citizens. Countries like India and the Gulf states would head the same way, while Europe and Japan would face geopolitical irrelevance (or worse, internal instability) as they fall behind in the race for AI supremacy.

Dystopian scenarios such as those outlined here can be avoided, but only if decentralised open-source AI models end up on top. In Taiwan, engineers and activists are crowdsourcing an open-source model built on DeepSeek, hoping to keep advanced AI in civic, rather than corporate or state, hands. (The paradox here is that DeepSeek was developed in authoritarian China.)

Success for these Taiwanese developers could restore some of the decentralisation the early internet once promised (though it could also lower the barrier for malicious actors to deploy harmful capabilities). For now, however, the momentum lies with closed models centralising power.

History offers at least a sliver of hope. Every previous technological revolution – from the printing press and railroads to broadcast media – destabilised politics and compelled the emergence of new norms and institutions that eventually restored balance between openness and stability. The question is whether democracies can adapt once again, and in time, before AI writes them out of the script.

Ian Bremmer, Founder and President of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media, is a member of the Executive Committee of the UN High-level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025, and published here with permission.

16 Comments

My wife is a choir director and writes her own songs. Where before she would pay someone to do a demo tape she now runs it through an app and gets perfect singing, any voice, any range, $20/mo instead of $50/hr.

$10k pa became $240 pa. A whole lot of jobs are disappearing fast.

Content creation, editing, proofreading, transcribing, recording etc is now essentially free. As is the cost for legal and tax research what used to get farmed out to grads.

And that money from those income/job losses will transfer over to the owners of that AI.

Yes. But a lot more small businesses will be able to develop things faster and cheaper

If we looked at the last few decades of technological innovation and disruption

Would you say the lions share of financial gain has been for the owners of the technology, or the users?

The users if on total gain. The providers if on unicorn businesses who capture a moment

Australian authors challenge Productivity Commission's proposed copyright law exemption for AI

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-13/productivity-commission-ai-repor…

Senior lawyer apologises after filing AI-generated submissions in Victorian murder case

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-15/victoria-lawyer-apologises-after…

Atlassian co-founder Scott Farquhar has been outspoken about the need to reform Australia's copyright laws to facilitate AI investment and innovation, particularly for LLMs. Farquhar argues that Australia’s current copyright rules - which lack provisions for “fair use” and have stricter “fair dealing” exceptions compared to the US, UK, and EU - are blocking billions of dollars in AI investment. He suggests that updating these laws would unlock major economic benefits and enable local companies and international AI labs to train and host AI models in Aussie.

He wants the right to access people's content. Of course for free. And of course, Atlassian's solutions are not 'open source'.

https://www.capitalbrief.com/newsletter/farquhars-copyright-clash-14050…

I sorta lament the Internet's wasted potential in improving democracy. Instead of being a source of better information for the public to collaborate and make informed decisions over, the economic incentive for click bait means everything is about triggering emotions.

I don't hold out much hope with uptake of AI. It appears it will bias it's reply based on what it thinks the question typer wants to hear.

" It appears it will bias it's reply based on what it thinks the question typer wants to hear."

So its been trained on politicians?...perhaps that is the future, AI generated political avatars.

Most of our money in its various forms is tied up in the internet.

When I vote for everything from the School Board to AGM of listed companies I have shares in I can do it online.

But local and central government elections are still paper based. The establishment is terrified of what will happen when voting moves online

It is simple: one citizen = one unique digital ID. I believe Estonia has done it. Every piece of data anyone holds about you must include the unique ID and every citizen can search every database for their own content. Then move from representative democracy to true democracy.

Yes...they're terrified of a more robust democracy & losing control of their agenda (across the political spectrum/Overton window)

Many new computer science graduates in the U.S. are struggling to be relevant. Despite years of messaging from tech leaders and politicians promising lucrative opportunities for those who learn to code, many graduates now find it extremely difficult to land tech jobs - some apply for hundreds or even thousands of positions with little to no success.

- Major tech companies like Amazon and Microsoft have laid off workers and are adopting AI coding tools, reducing the need for entry-level coders.

- Many computer science graduates report being ignored by tech firms, getting few interviews, or only hearing from non-tech employers like Chipotle.

- The hiring process is described as “bleak” and “soul-crushing,” with lengthy application procedures and extensive use of automated resume filtering.

- The shift is attributed to a combination of over-hiring during the pandemic, aggressive cost-cutting, the rise of AI, and changes in corporate hiring practices.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/10/technology/coding-ai-jobs-students.h…

What happens if different AIs from different countries/companies start interacting with each other on the internet?

Skynet

What happens when post-collapse, the grids go down?

All of a sudden, no medical advice - we find we've no real doctors.

Etc.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.