Jensen Huang believes questions of whether artificial intelligence could destroy humanity are fear-mongering – and get in the way of progress. The founder of Nvidia, which makes the computer chips enabling AI such as ChatGPT, he was rankled when a journalist wondered if he is “an AI Robert Oppenheimer”. He’s not building bombs, he responded.

But for journalist Stephen Witt, what he terms “The Fear” (shared by arguably “the three most cited computer scientists alive”) was a motive for writing The Thinking Machine, his history of Nvidia. His book, which doubles as a biography of its founder, asks: what does the artificial intelligence Nvidia facilitates mean for the future of humanity?

Review: The Thinking Machine – Stephen Witt (Penguin)

Nvidia is currently one of the world’s most highly valued companies. At over A$5 trillion, its valuation is close to that of one of its largest customers – Microsoft.

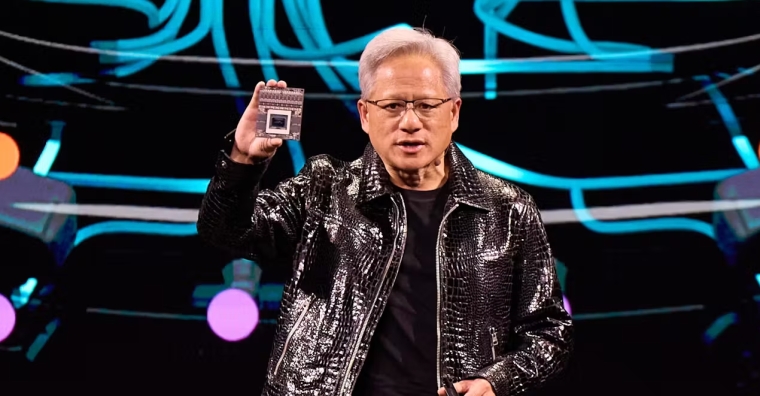

Founded to produce video game graphics, Nvidia pioneered “parallel processing”: doing more than one thing at a time. It developed an electronic circuit board that can quickly perform many mathematical calculations, called a “graphics processing unit” (GPU). Then, Nvidia looked for other users who needed a lot of computing power.

When its equipment was applied to “neural networks”, or computer systems which mimic brains – a key technology in AI – it struck the goldmine.

Huang believes AI is a force for progress, spurring a new industrial revolution, writes Witt. Huang enthused “the marginal cost of calculation has gone to zero, and this has opened up incredible possibilities”. He dismisses concerns, saying of AI: “all it is doing is processing data”.

A success story

Jensen (originally Jen-Hsun) Huang was born in Taiwan. His family’s story is a classic example of successful immigrants. His father was a chemical engineer and his mother a primary teacher. They were hardworking parents who made sacrifices to give their children successful lives. They sent Jensen and his brother to stay with an uncle in the US when he was ten and joined him two years later, Witt writes.

Jensen excelled, both academically and at table tennis. He studied electrical engineering at Oregon State University, where he met his wife Lori. Both got jobs in Silicon Valley.

Witt compares Huang to Samuel Brannan, who became California’s first millionaire in the mid-19th century by selling prospecting equipment during the gold rush, rather than being a miner himself.

Nvidia boomed around the turn of the century, when Huang first became a billionaire. Its share price crashed after the dot.com bubble burst, but the company struggled back. By 2016, Huang was a billionaire again. He is now thought to be worth over US$100 billion. Nvidia’s 30,000 employees generate an average of over $1 million profit a year.

Nvidia contributed to work that won Nobel prizes in both physics and chemistry in 2017. Scientists used the company’s GPUs to analyse vast amounts of data generated by laser beams, detecting gravitational waves, and the detailed structure of single cell organisms. This helped them learn more about phenomena at both a very large and very small scale.

But when its GPUs began to be used to mine bitcoins, “many inside Nvidia were appalled”. Witt reports that many of the Nvidia engineers to whom he spoke “regarded crytpo as an idiotic distraction from the company’s far more important work” and were concerned about the energy-intensive crypto mining’s contribution to climate change.

A CEO for longer than Bill Gates

Huang has only recently become widely known. Yet this overnight sensation has spent 32 years as CEO – longer than Bill Gates led Microsoft.

He works over 12 hours a day, six days a week. Perhaps this is why neither of his children initially wanted a career in tech, writes Witt. His daughter wanted to be a chef and his son a photographer. But both ended up at Nvidia: the daughter is a marketing director and the son is in the robotics group.

Huang described himself to Witt as “a serious person doing serious work”. Huang could be a demanding boss, and could shout at employees in front of their peers when disappointed with their performance. But he would try to lift their performance; dismissing them was only a last resort. He could be very generous to staff facing medical problems.

While Witt calls Nvidia’s headquarters a “panopticon”, most of his staff seem to like it – and to hold Huang in great esteem. As Nvidia says in its annual report, “our employees tend to come and stay”. Of course, as Witt notes, working at Nvidia has made many of them “insanely, incredibly rich”.

Witt seems to admire Huang. He describes him as “charming, funny, self-deprecating” and a “family man” who keeps his political views to himself. Unlike some of his peers, he does not seem to assume that being rich and a talented engineer makes him the smartest person in any room and an expert in any field. He was not part of the Greek chorus of plutocrats at the Trump inauguration.

He seems as grounded as a centibillionaire could be.

Thinks like an engineer

Huang had not read Witt’s New Yorker profile, the basis for this book, but helped him meet contacts to write it. Witt feels Huang “doesn’t think like a businessman, he thinks like an engineer”.

To draw a superhero analogy, it seems to me Huang is more the talented, workaholic genius Reed Richards of the Fantastic Four than the volatile, arrogant Tony Stark from Iron Man (who is often compared to Elon Musk).

Witt suggests Huang has taken over Steve Jobs’ position of “visionary tech executive with a signature outfit […] an important ceremonial role in American culture”. Around 2015, Huang developed his look: a black leather jacket with black trousers and shoes.

What he has not developed is a succession plan. None of the 55 staff directly reporting to him is a designated deputy, Witt writes.

Important questions about AI

Witt sees the development of AI as fulfilling the 1964 vision of science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke. Huang would be less keen on a later work by Clarke, who co-wrote the screenplay of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, depicting a sentient computer that kills humans.

The Thinking Machine contains an interesting debate on the dangers of AI. By the end of the book, Witt still seems to have “The Fear”, despite Huang’s assurances.

I’m inclined to agree with Huang that AI deleting humanity is unlikely. But it should be given more consideration than Huang seems to think.

This is not the only risk posed by users of Nvidia’s GPUs for AI. They use a lot of electricity. Witt observes that a student getting ChatGPT to write an essay uses as much power as running a microwave for an hour. A Google search using AI consumes ten times the power of a standard search.

On the other hand, Nvidia staff have also used their chips to run complex climate models, which may help develop policies to abate and adjust to global heating, Witt writes.

Like Kara Swisher’s Burn Book, this is a book about the tech world that a non-tech audience may find very interesting.![]()

*John Hawkins, Head, Canberra School of Government, University of Canberra.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.