This is a re-post of Box 4 in the Reserve Bank's November Financial Stability Report, here.

This Box introduces the concept of funds transfer pricing (FTP), explains how a bank manages its exposure to interest rate and liquidity risks through its treasury operations, and discusses how FTP can influence banks’ business decisions.

Banks are typically structured into multiple business units – such as rural and commercial banking, home lending, and retail deposit taking. FTP is the framework that banks use to allocate the costs of funding and returns from lending activity across these units. This provides a benchmark for a bank to assess the contribution that different business units make to the banks’ overall profitability. For example, banks can assess how much interest income the home loan unit makes above the costs of funds it employs, and the risks being taken. FTP helps to ensure that a bank is pricing its loan and deposit products effectively, while centralising risk management. It can also be used to adjust the shape of a bank’s balance sheet over time.

Treasuries play a central role in banks

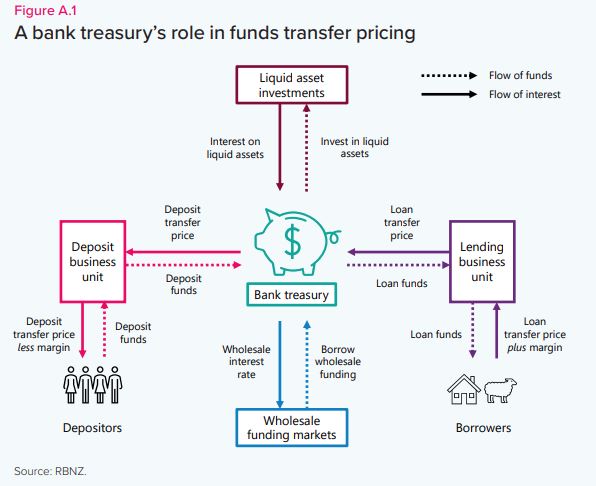

When deciding the interest rate for a loan, a business unit may not know where and at what cost the funds for that loan were obtained. Similarly, a deposit-gathering business unit does not know what loans those deposits will be funding, or how much interest the bank will earn on that lending. A bank’s treasury effectively operates as a ‘bank within a bank’. It receives funds from deposit-gathering business units and allocates the funds to lending business units. It uses FTP to send price signals to the business units about the cost of funds and return on funds (figure A.1).

In this role, the treasury also centralises the management of interest, funding, and liquidity risks. For example, many borrowers like to gain interest rate and cashflow certainty by fixing their interest rate. From a bank’s perspective, being on the other side of a fixed-rate loan means they are open to interest rate risk, which can leave them exposed to economic gains or losses if market interest rates move unexpectedly.

Each business unit is charged appropriately for the funds they use, or credited for the funds they provide, meaning that they have a more stable view of the margin they contribute to the bank. This frees up business units to focus on objectives like portfolio growth and market share.

How a bank estimates its cost of funds

To determine the cost to the bank of funding at different time horizons, a bank takes several steps to construct an internal funding cost curve as part of its FTP methodology:

• Setting a base rate: creating an interest rate curve that provides a foundation view of interest rates at different repricing terms. New Zealand’s major banks’ loan portfolios are larger than their deposit portfolios, meaning wholesale funding is used to close this gap. Typically, they use wholesale interest rates such as the OCR and interest rate swap rates at different maturities as funding cost benchmarks, since these reflect the opportunity cost of creating new loans or taking in new deposits.

• Incorporating additional funding premiums: adjusting the base rate curve to account for deposit stability, loan duration, and the bank’s own credit risk premium. A bank typically pays a credit risk premium above the swap rate when sourcing funds in wholesale markets, and a term premium for longer duration funding. A corresponding amount is added for different loan and deposit offerings based on their expected duration.

• Adding liquidity costs: some types of funding can be withdrawn at short notice. Similarly, loan facilities that customers can draw down on at a future date generate liquidity risks for the bank. To manage liquidity risks, banks hold a buffer of liquid assets. These assets typically earn less interest than loans. Therefore, the FTP framework assigns a higher cost to funding and lending offerings with greater liquidity needs.

The exact FTP methodologies that banks use varies, depending on the complexity and nature of their business models. Smaller New Zealand banks often have simple business models that don’t rely as much on wholesale funding. When setting interest rates, they may find it more appropriate to use average deposit costs rather than a wholesale market funding curve with risk adjustments. While setting the base rates is relatively straightforward, and based on objective metrics like wholesale interest rates, there is a larger role for discretion and judgement in the other parts of the FTP methodology. Moving from the internal transfer price to the customer interest rate Once it has constructed an internal funding cost curve, a bank will use this to determine the appropriate cost for different loan and deposit offerings. To calculate a home loan rate, for example, the bank treasury will assign a loan transfer price at the appropriate term on the internal funding cost curve to the home lending business unit.33

Starting from the transfer price, the home loan business unit will add allowances for:

• Expected losses: the bank expects a small proportion of loans to incur losses in any given year, which is accounted for through pricing.

• Capital charges: capital enables the bank to absorb large but infrequent unexpected credit losses. The bank needs to fund a portion of its lending with capital (e.g. equity) to meet its regulatory capital requirements set by the Reserve Bank. The amount of capital depends on the riskiness of the lending.34

• Operating costs: the cost of systems and people needed to create and manage the loan.

The difference between the final customer rate that the bank charges and the sum of these components represents the profit that the lending business unit is contributing to the bank as a whole (figure A.2).

On the funding side, the bank treasury will assign transfer prices to deposit-gathering business units to compare the interest rates paid on each type of deposit. The transfer prices reflect the value of the funds they receive. For example, a 6-month term deposit rate offered using the FTP methodology will be based on the internal funding cost curve, adjusted for the expected maturity of the deposit. Typically, deposits are a very stable source of funding for banks, and so the average maturity of deposits is often longer than their contractual maturity. For instance, a bank may assume that an on-call or 6-month term deposit will in practice have an average maturity of 2 to 3 years.

To calculate the deposit rate paid to customers, the deposit gathering unit then deducts operating costs, and the profit that the deposit-gathering business unit is contributing to the bank from the transfer price (figure A.2).

Some deposits, such as transaction accounts, pay minimal or no interest. As a result, they provide funding for much less than the transfer price, creating an important source of profit for many banks. Transaction balances represent around 18 percent of total bank funding currently. Changes in interest rates would result in volatility in banks’ profitability from these types of deposits as the OCR changes. Banks use hedging strategies to smooth out these changes in profitability over OCR cycles (see Chapter 4).35

The FTP framework provides different business units with neutral and clear pricing signals, which then allows them to set deposit and loan interest rate offerings in the market based on factors like market share ambition and desired profitability. In turn, by centralising liquidity and interest rate risks, FTP gives the bank’s management a more objective measure of each unit’s contribution to the bank’s overall profitability.

Adjustments and risks with funds transfer pricing

Banks in New Zealand each have their own FTP methodologies, and these can be adjusted over time depending on macroeconomic conditions or specific business goals. Banks continuously assess their FTP methodologies to ensure that appropriate pricing signals are being sent to business units, and apply adjustments based on judgement to achieve their strategic objectives.

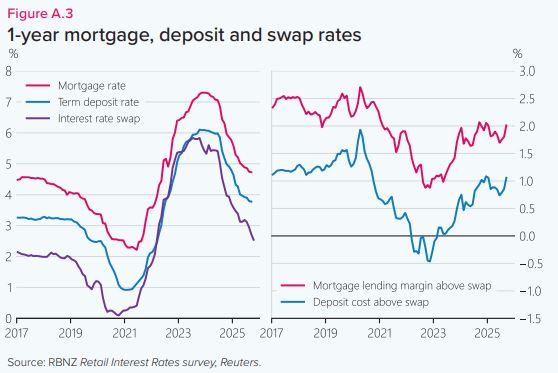

For instance, during the period of monetary policy tightening between 2021 and 2023, wholesale interest rates rose significantly faster than deposit rates (figure A.3). At this time banks were able to maintain relatively lower term and savings deposit rates, improving the profitability of these products from an FTP perspective. This reflected conditions of an abundant supply of deposits compared to demand (a consequence of the higher COVID-level period of savings, higher levels of liquidity, and weakening credit demand).

The impact of this development on margins would have depended on the nature of each bank’s FTP framework. Banks whose FTP frameworks closely aligned their internal funding cost curve with wholesale interest rates would have seen their loan margins decline during this time as the spread between lending rates and wholesale rates narrowed. In contrast, those banks whose methodologies put more weight on actual deposit costs would have seen less change in their loan margins. Such differences in FTP methodologies would influence how profitable a bank sees their loan book at a point in time, and how hard they compete with one another on loan pricing and for market share.

In addition to responding to macroeconomic developments, banks can use their FTP methodologies to tilt the composition of their balance sheet over time. For example, adjustments to pricing of the different components can be used to encourage longer-term deposits, assign higher costs for a bank’s liquid asset holdings, or to enhance the competitive position of specific business units for strategic purposes.

Footnotes

33 Typically, banks use an assumed behavioural maturity for a loan, rather than the legal contractual maturity. A home loan with an initial contractual maturity of 30 years will on average tend to mature well before this, typically within 5 to 10 years. This happens for a variety of reasons, including accelerated principal repayments, or the loan being restructured when the borrower sells their home to purchase another one.

34 See the RBNZ Bulletin article “How risk weights affect bank lending” (https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/hub/publications/bulletin/2024/how-risk-weight…) for further discussion on the role of risk weights and regulatory capital requirements in banks’ lending decisions.

35 Commonly New Zealand banks use interest rate swaps to convert their stable zero-interest deposit funding into a “replicating portfolio” that mimics a more market-sensitive funding structure. Instead of treating these deposits as zero-interest, zero-duration liabilities, banks construct a replicating portfolio of interest rate swaps with staggered maturities, for example dividing the value of these deposits into a 5-year rolling portfolio, with 1/60th of the portfolio maturing every month. The FTP framework can incorporate the replicating portfolio by assigning a transfer price to the deposits that is equivalent to a 5-year funding instrument.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.