By David Skilling*

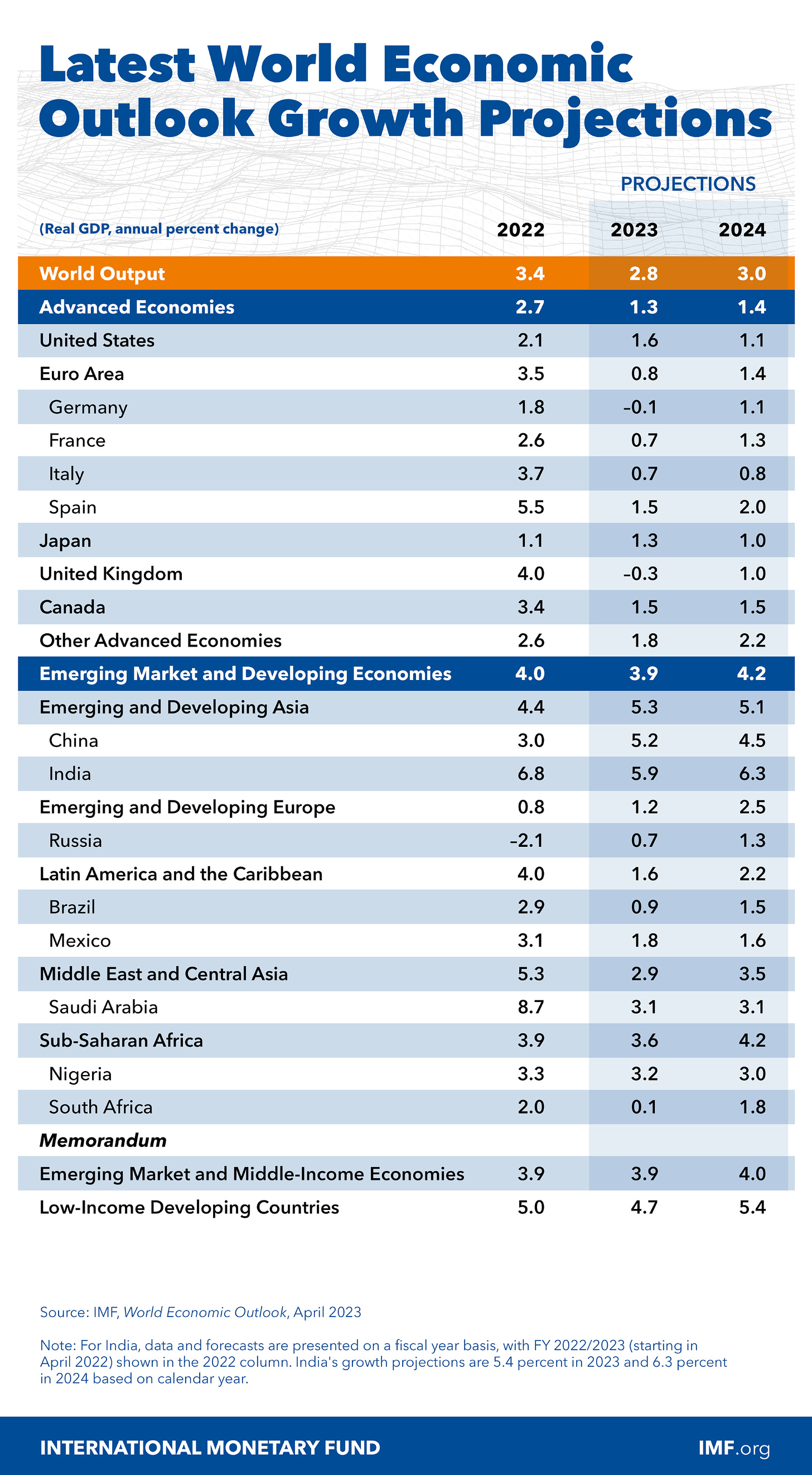

This week’s IMF World Economic Outlook reported that the global economic outlook over the next several years is as weak as it has been for a few decades. But the global economy is showing resilience against a range of headwinds and shocks, notably higher interest rates. And global growth is expected to pick up gradually from next year, in both advanced economies and emerging markets.

There are risks ahead, particularly relating to the impact of higher rates on the financial sector. The IMF Chief Economist noted that ‘We are therefore entering a tricky phase during which economic growth remains lackluster by historical standards, financial risks have risen, yet inflation has not yet decisively turned the corner’. Regular readers will know my view that this context will constrain further increases in rates, and that policy-makers will tolerate above target inflation for longer.

Beyond this near-term outlook, my key takeaway from the IMF reports (as well as from the WTO and others) is the speed and materiality of the structural changes to globalisation. Regime change is happening quickly.

Global trade dynamics

The IMF forecasts world export growth to average 3-3.5% from 2024 on, after ~2.5% in 2023, broadly in line with world GDP growth. World trade is not the global growth engine it was over much of the past few decades, but it is not retreating.

The WTO Trade Outlook, released last week, also reinforces the claim that global trade flows are changing rather than unwinding. Although merchandise trade volume growth is moderating after the Covid boom, world trade/GDP is expected to hold steady.

But there are significant changes underway in the nature of trade flows. There is greater corporate interest in reshoring activity; and industrial policy initiatives such as the Inflation Reduction Act are explicitly aimed at building domestic capacity and reducing exposure to global supply chains. And geopolitical fragmentation of some trade flows is already underway, as discussed in previous notes. Recent data, for example, shows large geopolitically-motivated shifts in semiconductor manufacturing equipment exports to China. The direction of travel is clear.

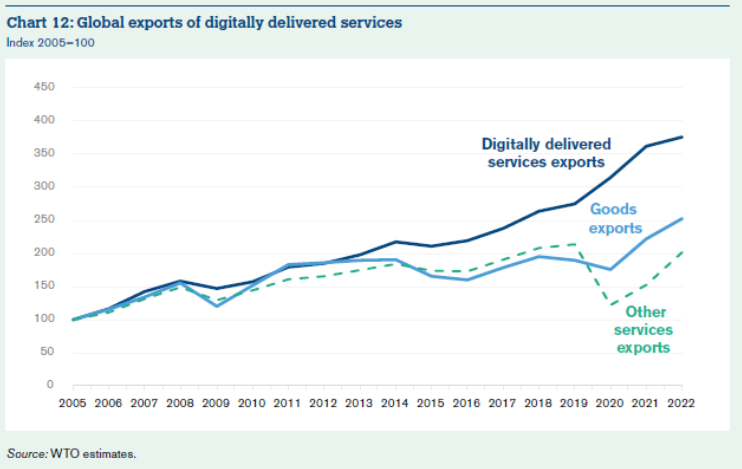

More positively, there are emerging growth opportunities in globalisation. The WTO reports that growth in digitally-delivered exports of services has been very strong over the past several years, increasing by >35% since 2019. Strong growth is expected to be sustained, although digital exports of services will also be subject to growing geopolitical alignment/friend-shoring pressures over time. This matters: these services account for ~13% of total world trade.

Globalisation is becoming more weightless. And it is striking that economic scale seems to be less relevant in determining competitive success in this area. The 12 small advanced economies that I track (~6% of global GDP) account for 26% of digitally delivered exports of services, well ahead of the 16% share of the US; Singapore, for example, accounts for 4.2%.

Fragmenting FDI flows

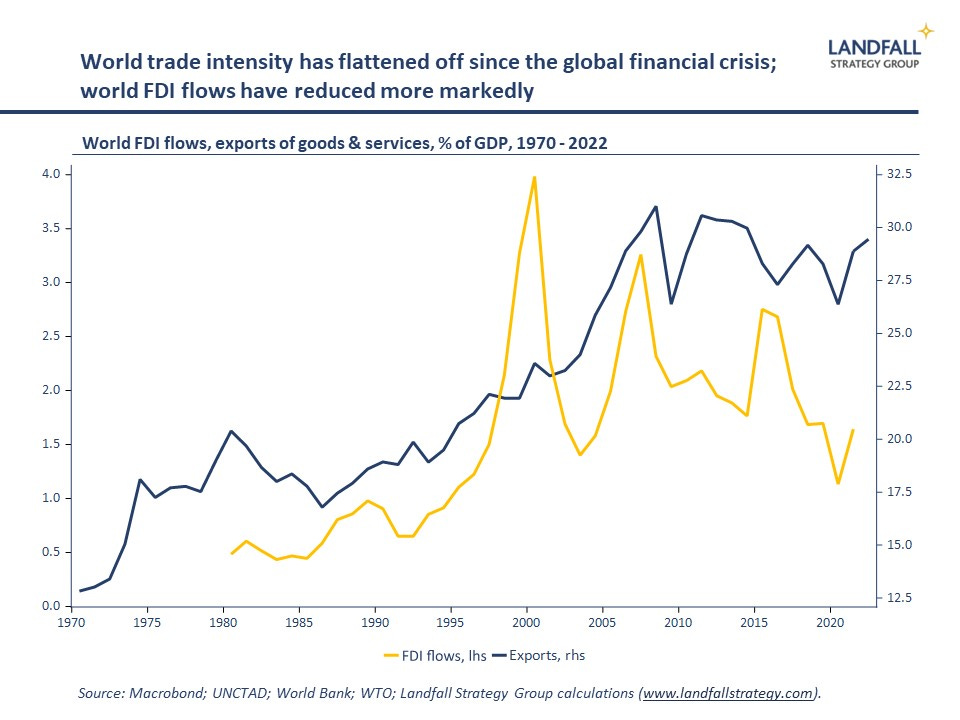

Global FDI flows grew strongly in the decades prior to the global financial crisis as firms established global footprints, by building global supply chains, undertaking M&A, and so on. These FDI flows supported rapid trade growth. And some global hubs, such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and Ireland, have economic models that are built around FDI.

Global FDI flows as a share of GDP have reduced over the past decade, in contrast to the flat trajectory of world trade, although this decline is partly distorted by tax-related flows. Looking forward, growing reshoring and friend-shoring activity will increasingly impact the scale and location of FDI flows.

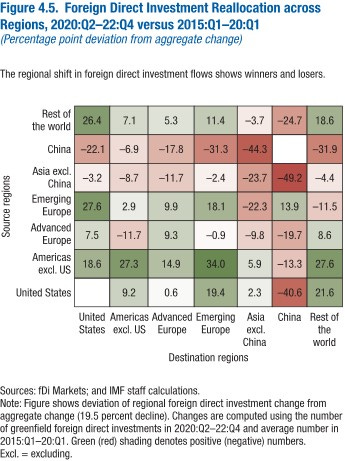

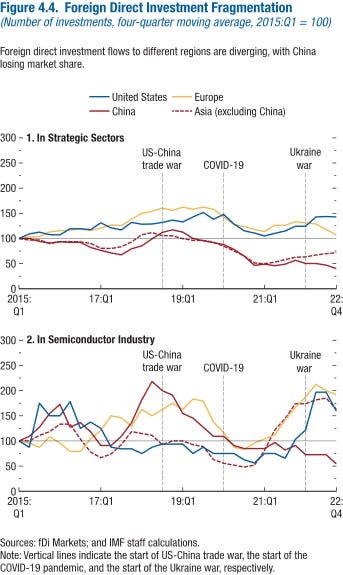

Analysis conducted for the IMF World Economic Outlook showed that geopolitics is already shaping FDI flows. The IMF reported that ‘FDI flows are increasingly concentrated among countries that are geopolitically aligned’. Investors are increasingly allocating capital to economies that are part of the same geopolitical blocs; for example, US firms investing in Europe or South Korea rather than China. The data also suggests that ‘geopolitical distance’ is more relevant to FDI flows than geographic distance.

Of course, part of the reason for reduced FDI inflows into China is the closed borders and other restrictions during the pandemic. But the outsized variation in FDI in strategic sectors (such as semiconductors) into different blocs over the past several years is instructive, suggesting that geopolitical factors have been relevant to FDI flows into China. Indeed, it is striking how much of an impact geopolitical tensions are already having on FDI flows: we should talk about geopolitics in the present tense not just the future tense.

Looking forward, the implication is that increased geopolitical tensions are likely to lead to FDI being increasingly concentrated within geopolitical blocs. There are various geopolitical scenarios, but a ‘hard fragmentation’ into closed, competing geopolitical blocs will have a strongly negative economic impact as FDI flows are distorted – the IMF assesses ~2% of global GDP – as countries lose the economic benefits that come from FDI.

The global economy will be less efficient than if geopolitical tensions did not exist. But we cannot wish this away. The counterfactual is not some idealised world of 20 years ago, but the real world when countries/firms do need to manage exposure to geopolitical rivals. Firms will incur greater costs if they ignore geopolitics.

The IMF assesses that emerging markets, particularly in Asia, are more exposed to geopolitical relocation of FDI because they receive FDI from a broad range of partners; whereas the EU and Europe receive FDI mainly from geopolitically aligned countries. However, the risk of FDI exit from geopolitically non-aligned countries is lower if there is significant market power in that country, as there may be few meaningful alternative locations (in some sectors, for example, China is dominant).

And much depends on the extent of geopolitical fragmentation. In plausible multipolar regimes, some countries may be able to position themselves as the location for FDI from across the geopolitical spectrum. Examples include Singapore and the Gulf states. FDI may be displaced to countries that can act as a bridge between geopolitical blocs and that have a compelling investment proposition.

These geopolitical dynamics will also reshape other international financial flows. The IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report notes that a rise in geopolitical tensions could trigger a large reallocation of portfolio capital flows. A reversal of capital flows could have significant effects on emerging markets that are reliant on external financing of current account deficits.

Adapting to a fragmented world

Firms and economies that are deeply exposed to global trade and investment flows need to adapt their business and growth models to these geopolitical dynamics. Corporate strategy and national economic strategy will increasingly need to reflect the geopolitical positioning of their home market.

Some of the dynamics around reconfiguring supply chains and market footprint may be efficiency-enhancing, strengthening the resilience of global activities. But the fragmentation of global supply chains along geopolitical lines is likely to lead to inefficiencies, costs, and risks for firms and economies relative to baseline conditions of the past few decades. To remain competitive in markets (and maintain margins) increased firm productivity will be required. And monetary policy will need to adjust to this negative structural supply side shock.

But there are opportunities as well: new growth areas in the weightless economy for small economies; new opportunities to attract geopolitically-aligned FDI (and portfolio investment) that is disrupted from its current location; as well as opportunities to invest in geopolitically-aligned offshore markets that are aiming to strengthen productive capacity through industrial policy.

Already there are examples of firms, investors, and economies responding to these opportunities. Those firms, investors, and economies that quickly adapt to this rapidly emerging global regime are more likely to prosper, even in a challenging global economic and geopolitical context.

If you have not already, you can subscribe for free to receive occasional public notes - or take out a paid subscription for full access to these notes:

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

5 Comments

One of David's better efforts. But as always, the theory is one thing, the reality...

Beyond this near-term outlook, my key takeaway from the IMF reports (as well as from the WTO and others) is the speed and materiality of the structural changes to globalisation. Regime change is happening quickly.

Summers Warns US Is Getting ‘Lonely’ as Other Powers Band Together

-

Former Treasury chief speaks on sidelines of IMF meetings

-

Summers: some voices see US representing less-favorable bloc

Singapore just elevated its ties with China following PM Lee's meeting with Xi Jinping in Beijing --- aaaand like clockwork

But @Audaxes if that FDI reallocation by region grid is correct, it looks like it is China that is getting lonely, rather than the US? The negative FDI figures, both in and out, are in relation to China...

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.