Like New Zealand, Australia is facing some serious economic challenges. Three stand out – improving productivity growth, achieving budget sustainability, and maintaining resilience in the face of global economic and geopolitical instability.

To address these challenges, the Australian federal government is holding an ‘Economic Reform Roundtable’ in Canberra next week. It will be attended by ‘a mix of leaders from business, unions, civil society, government and other experts’.

Cynics rightly question whether such a diverse group can achieve the government’s desired ‘consensus’ on ways to improve productivity, budget sustainability, and economic resilience. Or whether this will just be another pointless talkfest.

Early indications are not encouraging. This week the Australian Council of Trade Unions, the country’s peak union body, proposed a 4-day working week (on the same pay and conditions) as the key to boosting productivity. According to ACTU president Michele O’Neil, ‘shorter working hours are good for both workers and employers’.

This follows the Victorian state government announcing two weeks ago that it will legislate to give employees the right to work from home at least two days per week. Again, this move is justified on the grounds of boosting productivity.

These ‘ideas’ will make for some interesting discussion between union and business leaders.

Tax reform was initially expected, rightly, to be a major focus of the Roundtable. There is widespread agreement that the federal budget is far too reliant on income tax revenue. Many previous reviews and reports have recommended a range of reform possibilities including increasing the rate of GST (10%) and its scope (current exemptions include food, health, and education), imposing higher taxes on the mining sector, and reducing various tax concessions for superannuation, trusts, and capital gains.

However, here too, early indications are disappointing. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has hosed down expectations on imminent tax reform. When questioned by a reporter last week, Albanese replied that ‘the only tax policy that we're implementing is the one that we took to the election’. And that was minor tweaking rather than major reform.

The problem for Australia, like so many liberal democracies, is that the government is constantly under pressure to increase spending. It usually fails to resist that pressure but without implementing any corresponding increase in revenue. The result is a significant structural deficit and rising debt.

As a percentage of GDP, Australia’s debt remains reasonable compared to many similar developed nations. However, there are numerous fiscal threats, including the rising cost of debt servicing, the explosive 8-10% annual growth in the $50 billion National Disability Insurance Scheme, the escalating cost of aged care for an ageing population, and the potential blowout in the cost of defence (with the Trump administration pressuring Australia to dramatically increase its spending).

The position is aggravated by runaway spending in some Australian states. Victoria and Queensland are each projected to have debt of around $200bn by 2029. This profligacy is only possible because of an implicit guarantee from the federal government.

Interest in the outcome of the Roundtable has been heightened by the release this week of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s latest ‘Statement on Monetary Policy’. For the third time this year, the RBA cut the cash rate – this time by 25 basis points to 3.6%, the lowest rate in two years.

Market expectations are for two further 25bps cuts by February 2026.

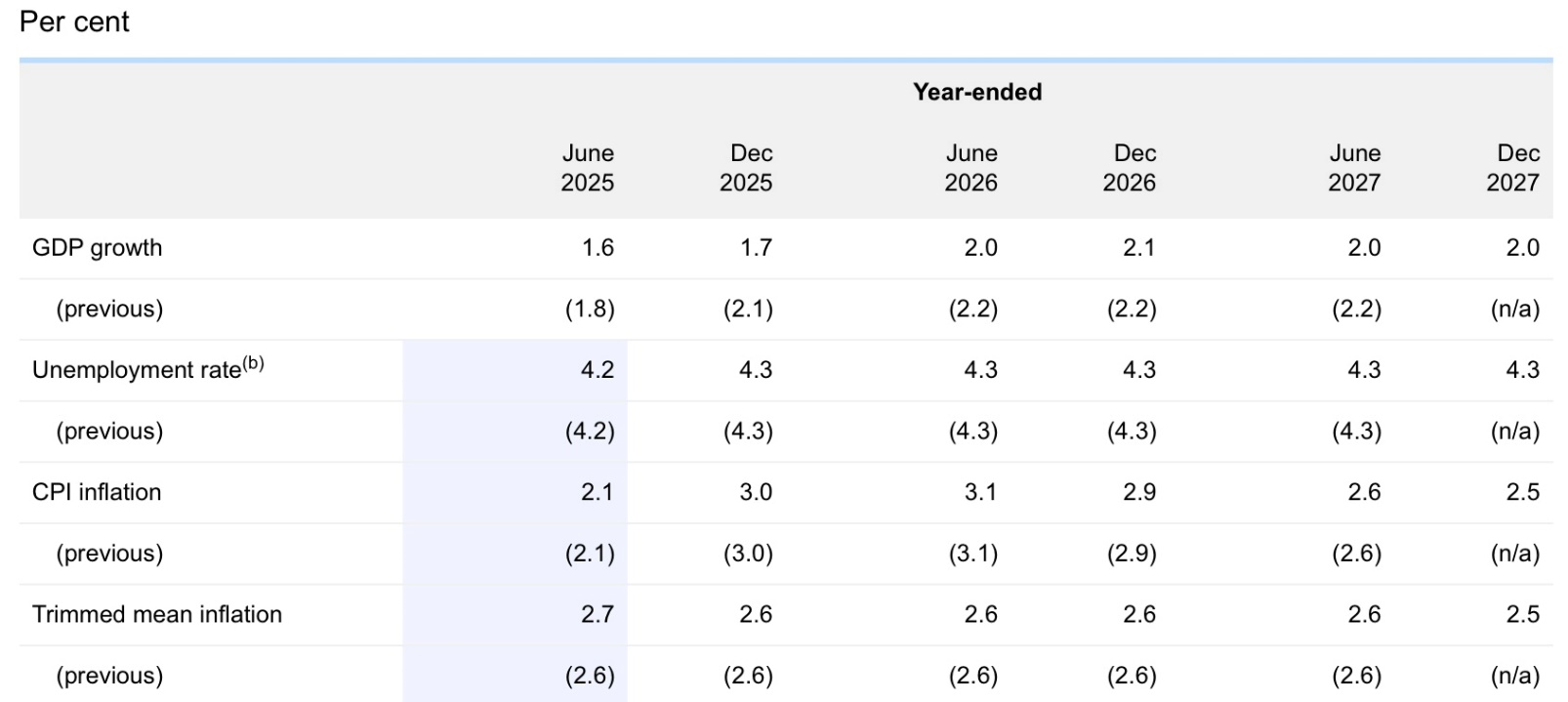

The key takeouts from the RBA statement are that inflationary pressures have eased and are now within the bank’s acceptable range of 2-3%, and labour market conditions have eased with unemployment expected to stay at around 4.3%.

Output Growth, Unemployment, and Inflation Forecasts

Source: RBA

However, the RBA’s updated forecast for GDP growth is a timely reminder of the importance of productivity – ‘GDP growth is expected to settle at a lower rate than previously forecast over the medium term, due to the lower outlook for productivity growth.’

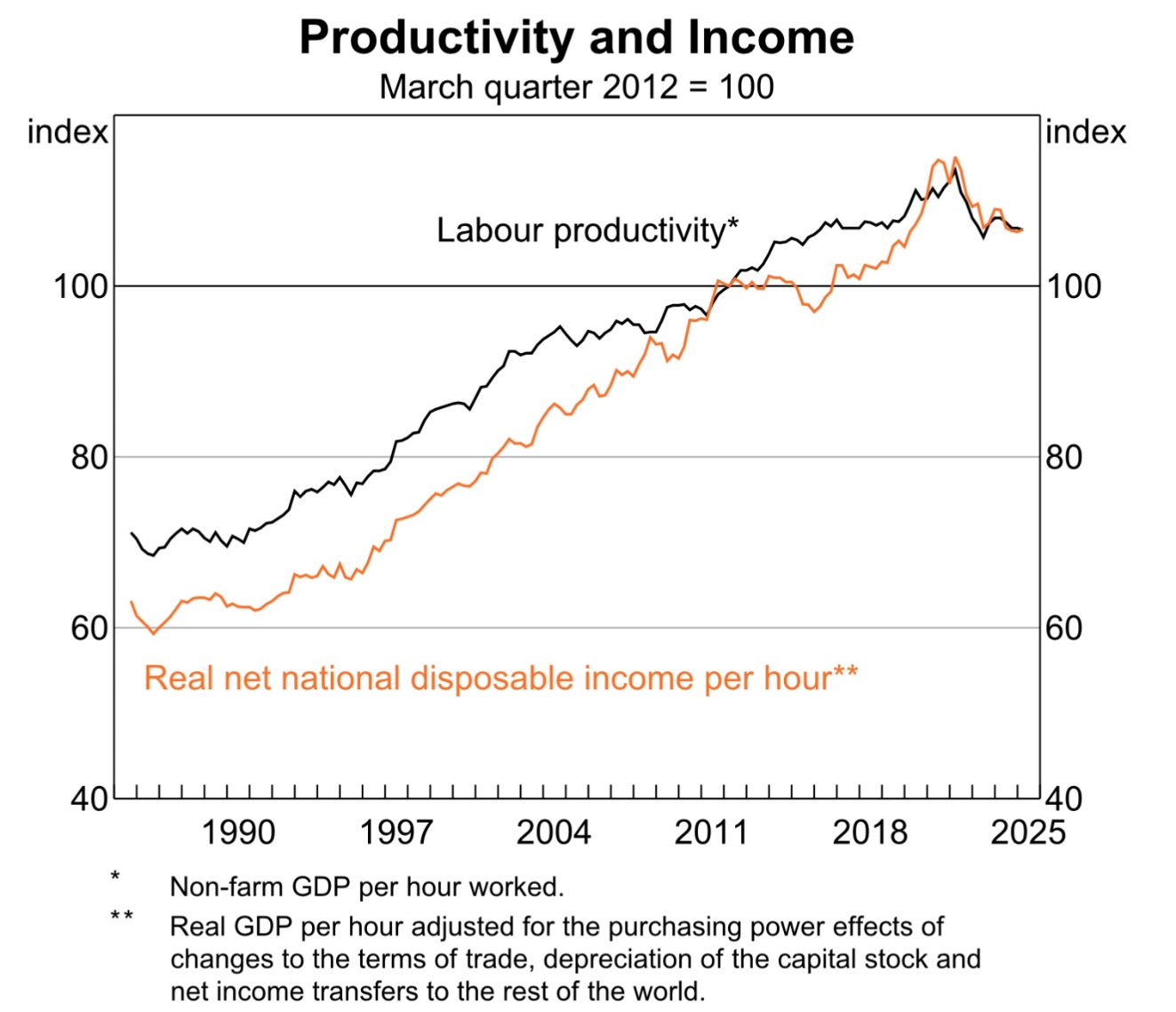

One section of the RBA statement should be compulsory reading for all attendees of the upcoming Roundtable – ‘In Depth – Drivers and Implications of Lower Productivity Growth’. It stresses that ‘Productivity is the key driver of growth in living standards over time’.

One graph says it all.

Source: RBA

What would a 4-day working week and a 2-day WFH guarantee do to that graph?

Another central topic at the Roundtable will be the ‘housing crisis’. House prices in Australia continue to rise, exacerbating the affordability problem, particularly for first home buyers.

According to Cotality, national dwelling prices rose by 0.6% in July, ‘the sixth straight month of gains, with the positive inflection aligning with the first (RBA) rate cut in February’. This week’s latest cut in the cash rate is expected to further stimulate house price growth.

Also of interest to the ‘Roundtablers’ will be this week’s data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. It reveals that in the June quarter the number of new housing loans to new owner occupiers rose by just 0.9%, but those to investors jumped by 3.5%.

So-called ‘mum and dad’ investors in the residential rental market are seen as a big part of the housing affordability problem of younger Australians. Many of those investors benefit from negative gearing and a capital gains tax concession.

These two features of the tax system will undoubtedly be debated at the Roundtable in the context of intergenerational inequality and the unsustainable federal budget. But given the government’s nervousness about the electoral implications of any kind of tax reform, no one will be holding their breath for change.

Like so many policy areas, it all looks too hard.

But Prime Minister Albanese’s Roundtable has raised expectations in many quarters. Unless it delivers, he may yet wish he’d never opened this particular Pandora’s box.

*Ross Stitt is a freelance writer with a PhD in political science. He is a New Zealander based in Sydney. His articles are part of our 'Understanding Australia' series.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.