By David Skilling*

Reading through a small mountain of 2026 outlook documents over the past few weeks, I was struck by the relative tightness of the consensus outlook. 2026 is widely expected to look much like 2025 in terms of economic and market outcomes. This includes a general sense of optimism in the global economic and market outlook for 2026 (AI, supportive macro policy). AI is seen as the major risk factor to this broadly upbeat assessment, along with some concern about inflation.

There are many reasonable aspects in this consensus view. But this consensus underplays the consequences of the broader regime change that is underway. The key risks and opportunities for the global economy in 2026 are geopolitical and political in nature rather than primarily economic. 2026 will likely be a disruptive year of accelerating structural change in the global economic and political context.

There are of course many possible developments in the year ahead that will matter. I select five dynamics that are not sufficiently reflected in the consensus view.

This is an abbreviated version of a note sent to clients last week. Get in touch if you would like to discuss these issues in more depth, and their implications.

1. Trans-Atlantic rupture

The Europe/US relationship has been under growing pressure in 2025: US tariffs; tech regulation; Trump Administration interventions in European domestic politics; differences over Ukraine; and more. And recent US action and rhetoric around Venezuela and Greenland create deep risks for Europe.

The European approach to these tensions has been to respond cautiously to avoid a blow up with the Trump Administration. But to the extent that the Trump Administration continues in this direction, as seems likely, these accumulating tensions are increasingly likely to cause a rupture in trans-Atlantic relations as Europe responds.

This will have first-order economic and market implications. European/US trade and investment bilateral flows are the biggest in the world. Some European derisking from the US would be likely in terms of trade flows.

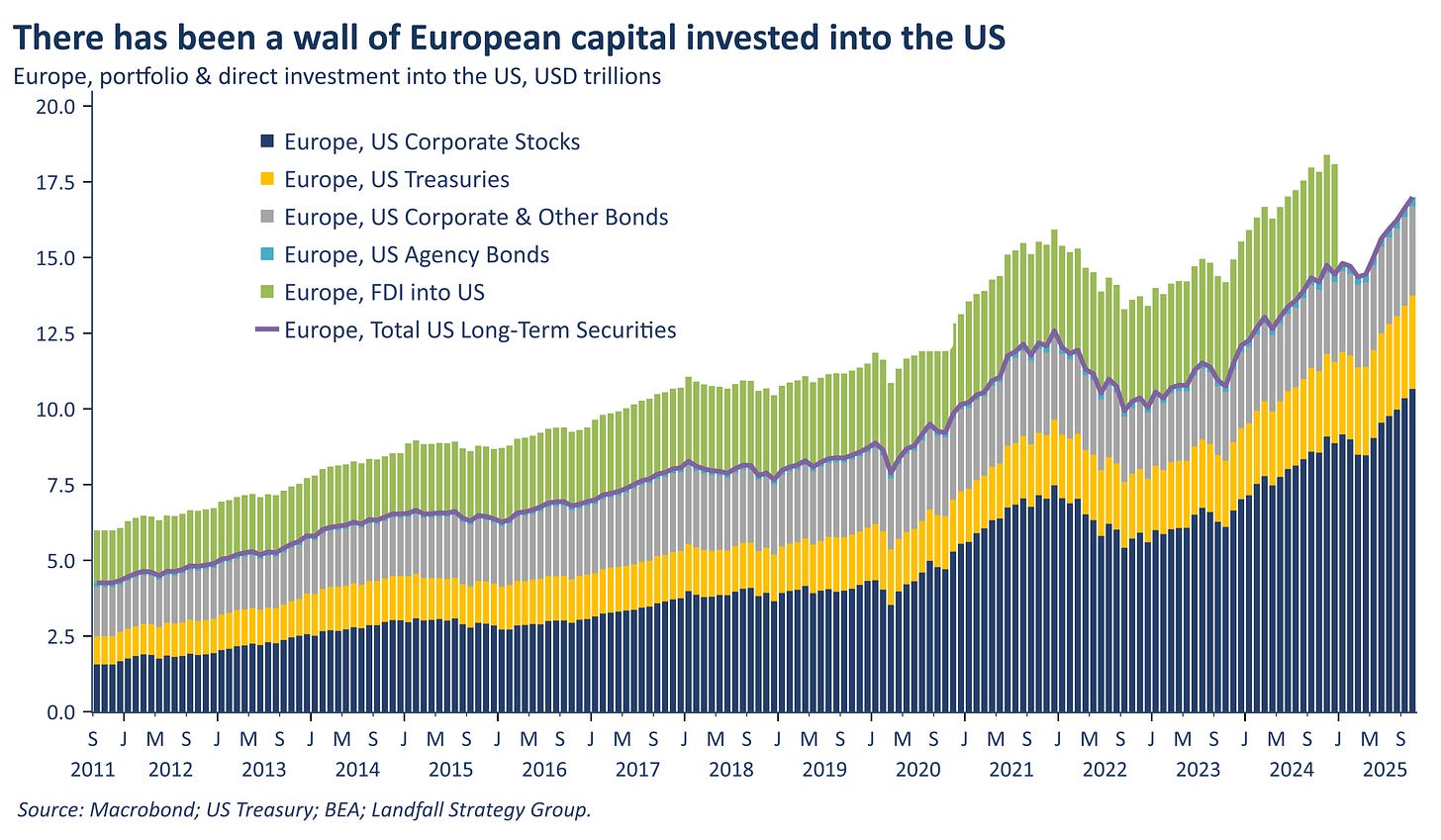

Another important part of a plausible European response to a rupture with the US is to reduce the allocation of capital to the US. European investors have $17 trillion invested in US portfolio securities, about half of the total foreign investment. In addition, there is $3.6 trillion in European direct investment into the US.

It was already likely that Europe would be exporting less capital to the US in response to growing European investment demand. The Draghi Report, for example, identified €800 billion/year in required strategic investment, >4% of EU GDP. A bilateral rupture would reinforce this dynamic materially. In important ways, European capital allocation decisions have supported US economic and market exceptionalism: a weakening or reversal of this process would be consequential.

2. China shock 2.0

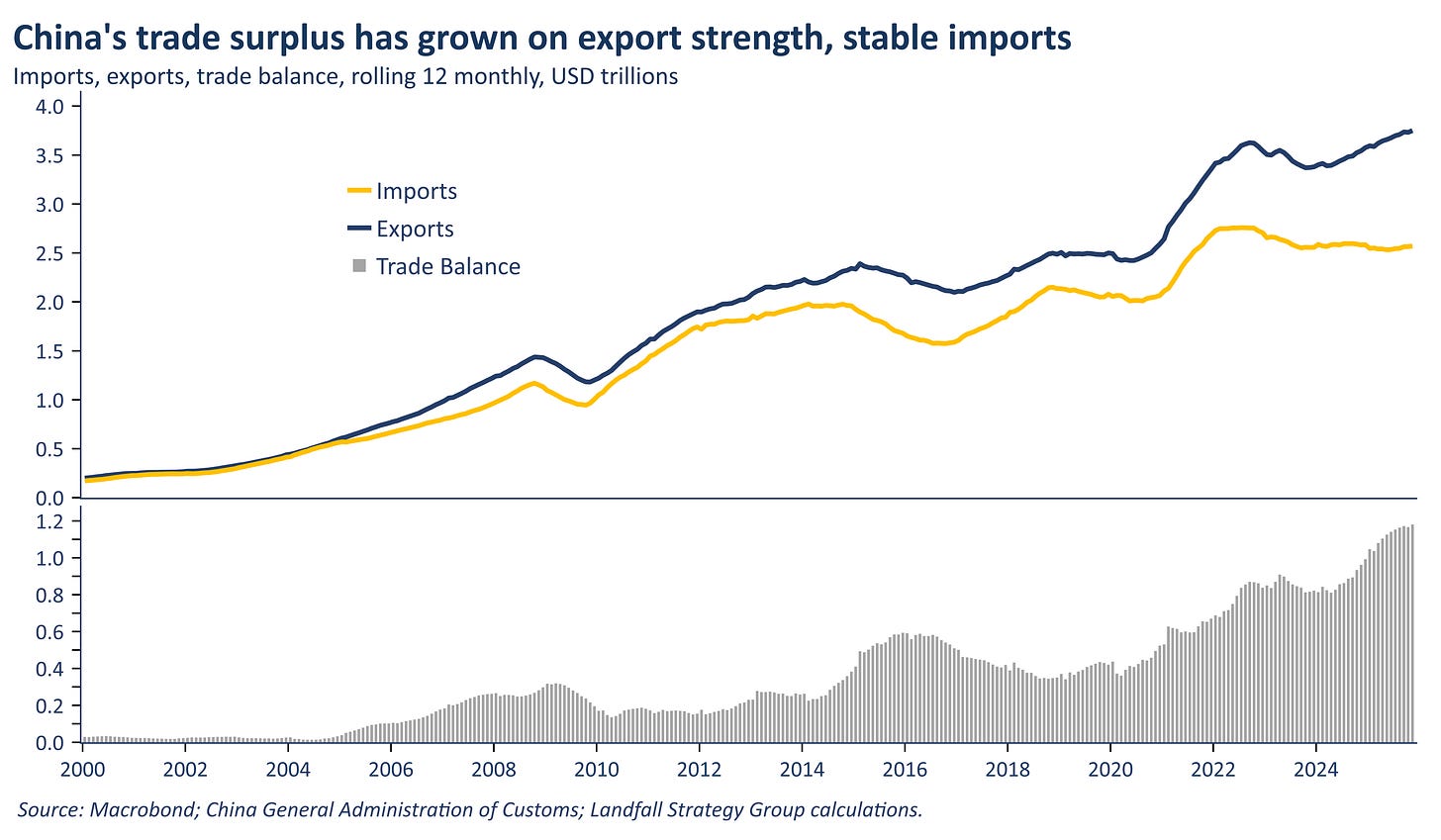

The impacts of China’s mercantilist approach to economic policy have become more evident through 2025. In the year to September 2025, China’s merchandise trade surplus was $1.2 trillion, or ~6% of GDP. China’s recent policy statements indicate ongoing commitment to developing export strengths as well as import substitution.

The scale of China’s industrial policy effort, combined with some export displacement due to US tariffs, means that many economies are being confronted with a wall of Chinese goods. The impact on industrial structures and labour markets across many parts of the global economy is likely to be consequential. Further barriers on Chinese exports are likely.

In response, it is likely that China will adapt aspects of its export-led growth model. There are two particular measures that are possible through 2026.

First, increased Chinese FDI into countries with which China is running trade surpluses. Investing in production facilities that create employment and activity in destination markets is one way of reducing the bilateral trade surplus and defusing some political pressure.

Second, to the extent that China adapts to place more weight on foreign investment rather than export income, there is more space for a revaluation of the CNY. On most measures the CNY is deeply undervalued, another source of international frustration with China. Upward pressure on the CNY in 2026 is more likely than is commonly assessed.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to receive my free public notes on global macro & geopolitics.

3. US as EM

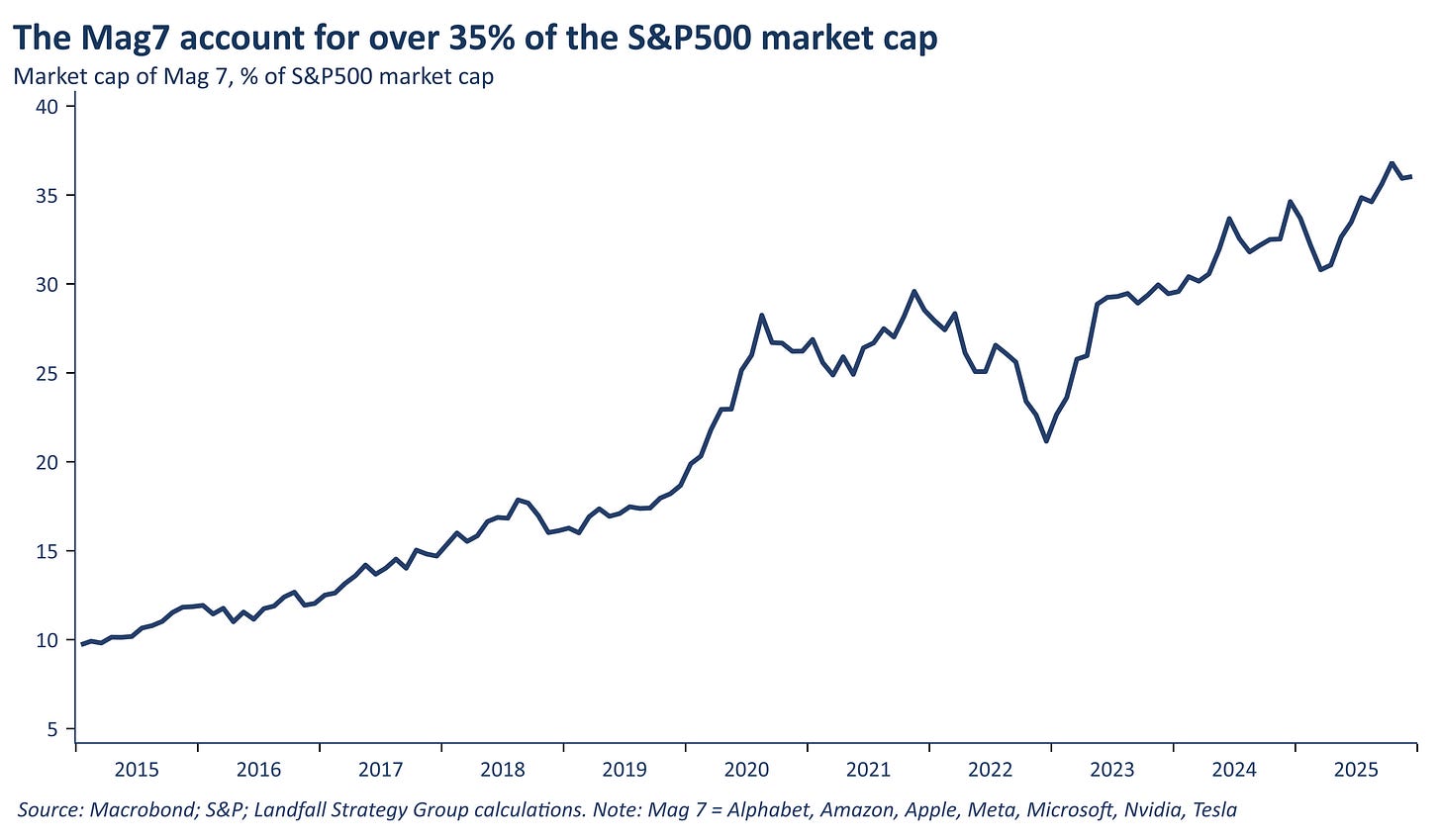

The US economic and market outlook is widely-recognised to be sensitive to the AI outlook. AI-related investment made a material contribution to the strong US GDP growth in 2025; and over 40% of S&P500 performance in 2025 was driven by the Mag7.

But the more consequential set of risks facing the US economy are political risks. The resilient performance of the US economy in 2025, together with a view that political forces will increasingly constrain President Trump’s second term, have reduced the salience of political risk. But this Administration is distinctive in many ways, and it is as likely that an institutionally-unconstrained and emboldened President will increasingly swing for the fences in both economic and geopolitical domains.

As a few examples: the process of nominating the next Fed Chair this year is likely to play out in a disruptive way that weakens Fed independence. And the Trump Administration is likely to act to further weaken fiscal sustainability. Mr Trump is increasingly weighing in on commercial decisions, ensuring that decisions reflect his personal views (from M&A deals to wind farms). And as the US government becomes increasingly engaged on industrial policy, there will be increasing scope for political interference.

The US will become a less predictable, riskier place to invest, with characteristics increasingly reminiscent of emerging markets. Policy risk will increasingly offset the substantial forces of innovation and dynamism in the US economy.

4. Fiscal dominance

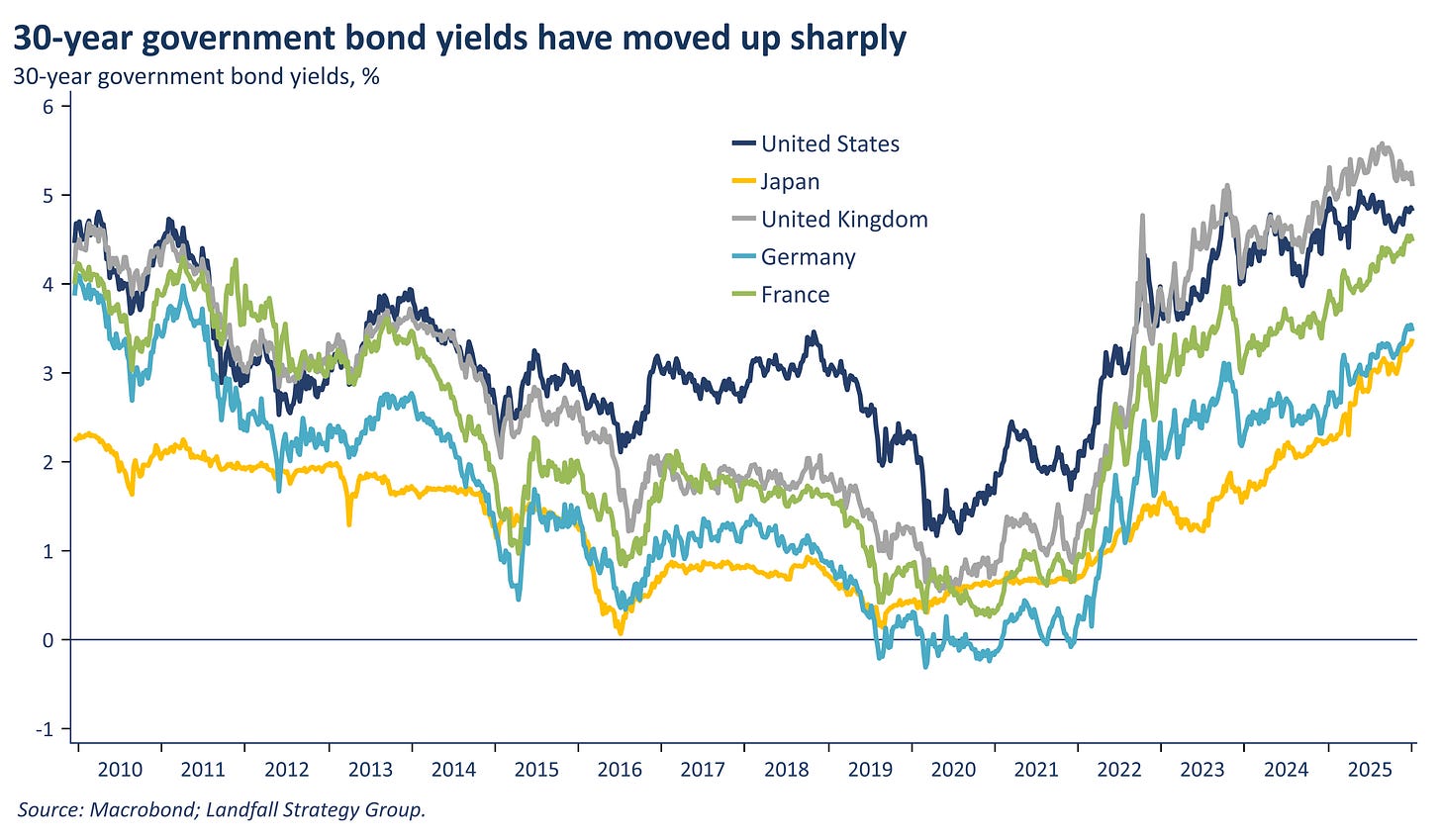

Yield curves steepened across advanced economies in 2025, as markets repriced risks around the fiscal outlook. 30-year government bonds have moved up sharply, even as shorter-term rates have reduced on expected rate cuts by central banks.

Looking into 2026, this is likely to continue. There is little chance of meaningful fiscal consolidation given higher borrowing costs, aging populations, strategic investment imperatives, as well as sharp political constraints on cutting spending or increasing taxes.

Given these realities, 2026 will likely see a more explicit integration of fiscal and monetary policy – with central banks more directly involved in financing government borrowing. In the US, the Fed has already reversed the quantitative tightening process and is purchasing US Treasuries again. The Fed balance sheet is likely to begin to grow again as a share of GDP. These dynamics will extend beyond the US, with the ECB and BoJ continuing to buy government debt in the context of worsening fiscal situations.

In the near-term, this will provide additional fiscal space – but watch for a shift up in inflation expectations, and a further steepening of yield curves. More broadly, this rewriting of the macro policy consensus will inject material risk into the global economy and financial markets in 2026.

5. Reglobalisation

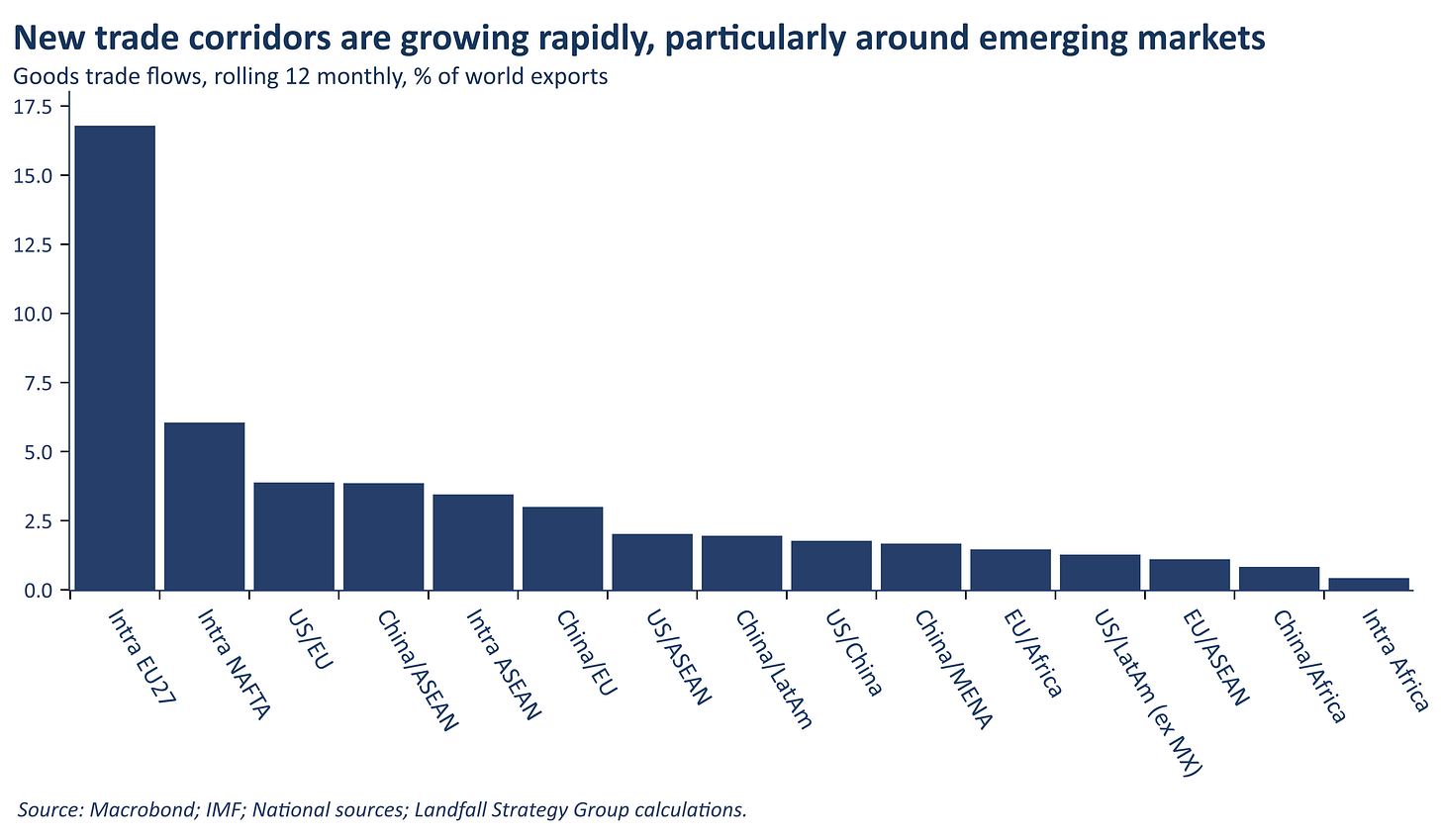

2025 has been a resilient year for world trade, a trend likely to continue in 2026 for several reasons. US tariffs, concerns about supply chain resilience, economic fragmentation on geopolitical concerns, have led to a reshaping of global trade flows rather than an unwinding.

But globalisation is being rewired. Global trade and capital flows will be increasingly shaped by geopolitical factors in 2026, with economies doing business with geopolitically aligned economies. State capitalism will also become more prominent, from the construction of vertically integrated global supply chains to government-led strategic trade and investment partnerships.

And new trade corridors are developing rapidly. World trade is tilting away from the US, a process accelerated by US tariffs; much of the strongest growth in trade corridors over the past several years is outside the Western world. New institutions are emerging that will shape trade and capital flows, from BRICS to RCEP.

Globalisation is not ending but is being powerfully reshaped, creating new sectoral and geographic growth opportunities.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

1 Comments

Perplexity a.i response to a question re the above bar graph on new trade corridors by country is quoted below-

'The underlying corridors imply that the EU has the largest associated trade flows, followed by China, ASEAN, and USMCA when totals are summed by participant bloc.

Totals by country/block

Rank Country/Block Total trade (% of world exports)

1 EU 21.8%

2 China 6.8%

3 ASEAN 6.8%

4 USMCA 6.0%

5 US 4.8%

6 Africa 2.1%

7 LatAm 1.8%

8 MENA 0.9%

Notes on method

-

Corridor values are first taken as shares of world exports, then split 50:50 between partners for bilateral flows and 100% to the bloc for intra-bloc flows.

-

These are approximate allocations, so totals are best read as indicative of relative scale rather than precise measurements.'

IMO this gives some perspective on who are the up and coming movers and shakers.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.