On Tuesday the Reserve Bank of Australia raised the cash rate by 0.25% - from 3.6% to 3.85%. This ends a short-lived cycle of rate cuts that began less than a year ago.

While markets expected the move, it makes the RBA one of the first central banks in an advanced economy to start hiking interest rates.

What prompted the RBA to move ahead of its counterparts in the US, the UK, Canada, and New Zealand? The spectre of rising inflation.

The latest inflation data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics revealed that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 3.8% in the year to December 2025, up from 3.4% in the November year. The trimmed mean, the RBA’s preferred measure of underlying inflation, was up 3.3% for the year versus 3.2% a month earlier.

Both figures exceed the RBA’s target range of 2-3%. According to Tuesday’s Statement on Monetary Policy, the bank now does not expect inflation to return to that range before 2027.

GDP growth and household consumption are stronger than previously anticipated by the RBA. This, combined with tight labour market conditions, has increased capacity pressures in the economy and lifted the price of many goods and services.

A rise in interest rates is bad news for borrowers. And it’s also bad news for the federal government coming so soon after three RBA rate cuts in 2025. Borrowers who were just starting to enjoy the reality of falling interest rates, and would-be borrowers who were getting ready to buy their first home, will be alarmed by this turn of events.

That’s not good for the government. Particularly, as last year it was very quick to claim the credit when the RBA cut rates.

There’s a strong argument that government policies are partly to blame for the RBA’s latest move. With the economy already operating at close to capacity in recent years, increased government spending has been expansionary. It has pushed up the price of many inputs, particularly labour, and crowded out the private sector.

This view has been expounded by many respected economists including HSBC chief economist Paul Bloxham and AMP chief economist Shane Oliver. Unsurprisingly, Treasurer Jim Chalmers disagrees.

Within half an hour of Tuesday’s rate increase Chalmers was posting on X.

We know many Australians are doing it tough which is why we continue to roll out responsible cost of living relief, including a further tax cut later this year and another one next year.

The irony of this sentiment will not be lost on many economists. It’s the government’s ongoing ‘roll out’ of ‘responsible cost of living relief’ that is part of the inflationary problem. The government has ‘spent’ billions of dollars on non-means tested electricity rebates. This year it’s introduced cheaper prescription medicines for all and heavily subsidised childcare three days a week even for non-working parents. It’s promising more ‘cost of living relief’ in the May budget.

All this government largesse is stimulatory at a time when the RBA is worried about capacity pressures in the economy. This scenario of government fiscal policy in conflict with RBA monetary policy is unfortunate.

Of course, the RBA does not directly criticise the government. Its latest Monetary Statement notes that recent growth in public demand was ‘in line with expectations’. However, it also points out that ‘budget estimates of the fiscal balance provide a more comprehensive view of developments in fiscal policy than public demand alone’ and that ‘the consolidated government deficit will continue to widen in 2025/26’.

Indeed, according to Treasury forecasts government expenditure will reach 27 per cent of GDP in the current financial year, a level not seen since the 1980s. Furthermore, budget deficits and rising debt are now forecast for the next ten years. There’s no end in sight to the red ink.

There’s plenty of expert advice on what the government should do. The IMF’s November statement identifies the need for ‘greater spending efficiency’ and ‘continued efforts to tackle fiscal and structural challenges’.

The OECD’s January economic survey also calls for ‘improving spending efficiency’. It states that ‘safeguarding fiscal sustainability will require a sustained consolidation effort at both the national and state levels to curb existing deficits and address longer-term pressures’.

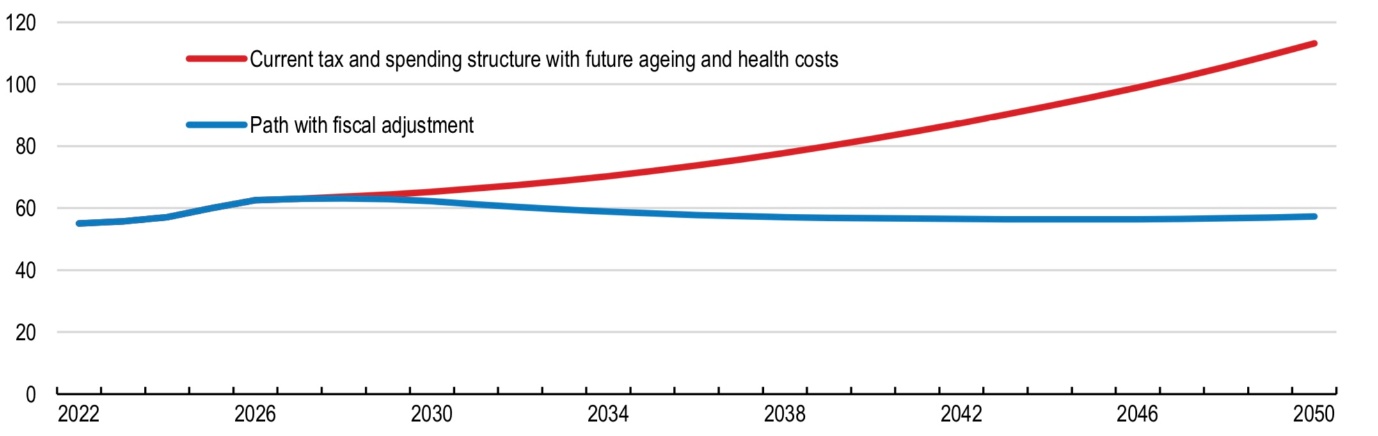

Australian gross public debt as a % of GDP

Source: OECD

It’s a grim picture. And the red line could climb higher still if, as seems likely, the coming decades bring their share of pandemics, financial crises, and geopolitical shocks.

Unfortunately, curbing deficits is not on the Labor government’s agenda. And to be fair it isn’t on the agenda of the opposition either. The policies that the supposedly ‘centre-right’ Liberal/National coalition took to the election last May were equally profligate.

The sad reality is that fiscal discipline is not a vote winner. Electoral bribes have become standard practice and ‘cost of living relief’ is just the latest iteration.

In their defence, politicians argue that Australia’s fiscal position is positively robust compared to most other developed countries. That’s true, but not thanks to the country’s recent crop of politicians. It simply reflects Australia’s remarkable mineral resources from iron ore, coal, and uranium, to lithium, gold, and rare earths.

Whatever the world needs, the ‘lucky country’ seems to have it.

It’s worth remembering where that label came from - Donald Horne’s 1964 book of the same name. He described Australia as ‘a lucky country run mainly by second rate people who share its luck’.

A prescient view of Australia’s political class in the twenty-first century.

*Ross Stitt is a freelance writer with a PhD in political science. He is a New Zealander based in Sydney. His articles are part of our 'Understanding Australia' series.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.