Financial bubbles are notoriously difficult to define in real time – until the moment they burst. To say with any conviction whether we are in one now, one must understand the magnitude and intensity of today’s AI investment boom, as well as the timing of the potential bubble’s end.

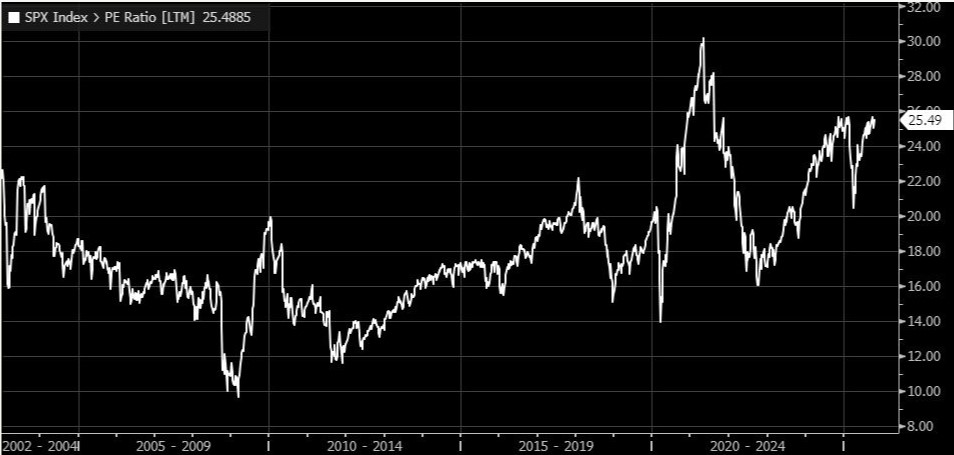

There are at least four ways to determine when a bubble is building in financial markets. The first is to look at valuations. Even when conventional valuation metrics such as price-to-earnings (PE) ratios reach excessive levels, the market might excuse this by focusing on new metrics to justify overvaluations.

For much of the past 25 years, the average PE ratio across the S&P 500 has been 16x, whereas now it is 25x. But this increase can be justified by focusing on the potential for new productivity gains from AI, or on products with a national-security value – such as semiconductors, which will be protected and ultimately backstopped by the government.

Moreover, some commentators argue that existing indicators like GDP simply are not capturing new sources of growth potential in the economy. For now, the fact that expected equity returns are higher than bond returns means that equity valuations are indeed “rational,” even if they seem high.

A second factor to consider is the prevailing narrative, which usually revolves around the message that “this time is different.” A bubble is almost always buttressed by belief in a new paradigm or emerging technology – whether it be the internet, the Japanese production process, electricity, railroads, or canals. The typical narrative creates a mental bridge between what actually is (current cash flows) and what could be (forecasts of future revenues).

The bridge is what lures investors to buy into a possible upside. While they may start by focusing on the rationally calculable growth forecasts of the business, the next step is to buy into an irrational story about an imminent economic transformation. This is when investing becomes overly one-sided, because it becomes hard to argue against the prevailing narrative.

Just in the past month, two start-ups have garnered eye-popping valuations by tapping into the AI narrative. Nano Nuclear Energy was valued at $2.3 billion despite having no revenue or even a license to operate; and the data-center energy supplier Fermi, which was founded only in January 2025, was valued at $14.8 billion.

Much like the 1980s Japanese bubble and the 1999-2001 dot-com bubble, the situation today may reflect a good, old-fashioned misallocation of capital, as everyone chases the new, shiny technology. The obvious risk is that investors will not get anywhere close to the returns they seem to expect.

A third indicator of a bubble is hidden leverage. Not only have investors and speculators continued to pile into overvalued stocks, but an increasing number have done so with borrowed money.

One finds growing leverage throughout the shadow banking system; but the greater concern, perhaps, is the risk embedded in financial products, such as leveraged exchange-traded funds. Even more ominous, the explosion of zero-day options (single-day bets on an equity’s price movement) suggests that more retail investors are engaging in leveraged trades whose risks they may not know how to manage.

This growing leverage – a common feature of bubbles, most notably the 2008 global financial crisis – implies that speculators, and the overall economy, are inherently exposed to more risk than they are aware of. According to FINRA, margin debt – the amount lent to investors by their brokers – reached a record high of US$1.06 trillion in August, a 33% year-on-year increase.

Lastly, a common feature of bubbles is circular dealing between companies. Many market participants are scrutinising recent deals in which Nvidia has agreed to invest $100 billion in OpenAI, which will use the money to pay Oracle, which will then buy chips from Nvidia. These sorts of arrangements were a major contributor to the Japanese equity bubble in the 1980s.

Assuming we are indeed in a bubble, the next question concerns when it will deflate or burst. While this inevitably requires guesswork, there are some important indicators to watch.

One is market sentiment. Currently, retail investors are driving a lot of the stock-price momentum, whereas institutional sentiment is neutral, meaning they hold Big Tech stocks but are not adding to their positions. But since retail is a relatively small share of the overall market, such exuberance can drive only a limited amount of asset-price inflation.

Another indicator is positioning. In simple terms, we will know that the bubble is inflating further if the institutional bid strengthens and becomes a long position, because this signals that institutional investors are giving up on other assets such as bonds, gold, or underperforming sectors (health care) and allocating more capital toward risk-on AI assets.

With most people only just beginning to learn about AI’s capabilities, it remains to be seen what new business models will emerge. As time passes, sophisticated professional investors will come to a better understanding of AI’s value and where cracks in the prevailing euphoric narrative may lie.

For now, there is a reasonable argument to be made that a bubble has only started to form. Judging by current market sentiment and positioning, the AI story seems closer to the 1996-97 stage of the dot-com bubble than to 1999-2001. The speculative behavior and valuations that we saw in the late 1990s have yet to be matched today.

Moreover, while the dot-com bubble was based on numerous startups, many of which with valuations that ultimately collapsed to zero, the AI boom revolves around global technology leaders like Nvidia and Alphabet, with established revenues and track records. That means there will be a higher floor under any drop in asset value, which suggests that the bubble is more likely to deflate than to burst violently.

Dambisa Moyo, an international economist, is the author of four New York Times bestselling books, including Edge of Chaos: Why Democracy Is Failing to Deliver Economic Growth – and How to Fix It. This content is © Project Syndicate, 2025, and is here with permission.

16 Comments

Print print print, pump pump pump. End of the day debt without supporting income is speculative gambling.

Role the dice.

The top 10% of American households own approximately 87% of all stocks and mutual fund shares in the U.S,, with some sources citing figures as high as 93% for the top 10% in certain periods. This means that while about 62% of Americans own some form of stock (directly or through retirement accounts), the vast majority of stock market wealth is concentrated among the wealthiest households (https://news.gallup.com/poll/266807/percentage-americans-owns-stock.aspx)

Not sure how this looks for Aotearoa.

So arguably the bubble is concentrated in few hands. And you could even argue the fallout would be greater among the rich than for the great unwashed if the bubble burst.

Top 20% of NZ households own 82% of financial assets. Next 20% own another 10%.

Top 20% of NZ households own 82% of financial assets. Next 20% own another 10%.

Makes intuitive sense.

Where would we find the data for this Jonny?

Probably need need to adjust that stat for age to make it meaningful. Pretty hard for the student flat to crack the 1%.

Wealth inequality in the US (and reflective of many other parts of western society) has exploded since the 1980's - 1990's. Top 1% (or even top 10%) wealth is increasing exponentially while the general population grind away on struggle street.

The wealth and income inequality is now back to where it was in the Gilded Age after being more or less eliminated post WW2 through to the 1980's. The gap between the rich and the poor is now back where it was in the 1920's which created the conditions/set the scene for the great depression. ie favouring one group too much over another (asset owners and capital growth over creating real world productivity and just rewards for labour/those willing to work hard (instead of speculating on asset prices)).

In NZ you need 8m net assets to be in top 1 percent. Australia and Britain are similar

That's beggar all, a lot less than I expected for Aus and UK

In NZ you need 8m net assets to be in top 1 percent. Australia and Britain are similar

8 million Kiwi pesos barely buys an average house in Sydney.

Aha, ok. But 23 aussie pesos only buys 26 kiwi pesos, until recently it was much closer to parity.

You're also seeing the trend of the Uber rich splashing out on big trophy homes in Auckland. This will probably increase under the Labour CGT model and the coalitions foreign buyer exemption.

Time will tell

I wonder if its as simple as those successfully self employed who spend time learning to select and control their own investments, vs those that rely on others for both activities.

I personally think government and central bank policies have in the past 3-4 decades been enabled to greatly reward capital (leveraged debt speculation) over labour (and I'm no socialist btw!)

If the system is better balance so that you get rewarded accordingly for working hard (labour), instead of vastly more rewards in recent decades for those speculating with debt to buy assets like companies and real estate, then wealth/income equality will resolve itself - as it appeared to do from the 1930's through to the 1980's. But nobody wants to face a pain similar to the 1930's in order realise that something dramatically needs to change - until then we hide our heads in the sand like ostriches and pretend that 'everything is going just fine' while deep down we know something is seriously broken economically/financially.

You published this graph earlier this year which illustrates that convincingly

Independent_Observer | 10th Mar 25, 6:01pm

Interesting chart from Hussman - wages from incomes vs corporate profits (adjusted relative to GDP).

Like the housing market, something appeared to break in the 1990s where massive $$ flowed into asset prices or corporate profits in comparison to remuneration to workers.

https://x.com/hussmanjp/status/1898780388316909754?s=46&t=MUwQeKa7MkEJ7…

I see AI being more profitable and crypto less so when the coming wave of cheap fusion power arrives.

And perhaps oil & gas will be priced out?

I see AI being more profitable and crypto less so when the coming wave of cheap fusion power arrives.

Investing in companies like IREN has been far better than rat poison and even Nvidia.

We are indeed in a dangerous bubble.

some additional drivers:

* Excess Liquidity provided by Central Banks and Government Borrowing since the GFC in 2008.

* Share markets are dominated by passive ETFs that in turn are governed by the performance of the MAG7.

* Markets have lost sight of fundaments and are driven by Flow and Mechanics.

In summary we have a debt/margin fueled euphoric rally with a positive feedback loop.....UNTIL?

Expect a 30 to 50% correction/bust.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.