Last week, it emerged that the Finance Minister, Nicola Willis has sought advice from Inland Revenue and Treasury on whether New Zealand's major banks are paying enough tax.

According to a release on policy work being undertaken by Treasury and the Reserve Bank, the Finance Minister “and the Minister of Revenue have commissioned Inland Revenue to review whether income tax settings are applying correctly to banks for potential consideration at Budget 2026.”

This is a clear implication that some changes may be ahead, or are being considered for next year's Budget, which coincidentally is also an election year.

“A wide range of options”

It appears Inland Revenue are considering, “a wide range of options.” What’s often brought up with banks is whether they have excessive levels of profits and therefore should be subject to a windfall tax.

The debate around excess profits and windfall taxes frequently arises. As the Greens rather ironically pointed out, Margaret Thatcher introduced a surcharge for banks in the early 1980s, when the monetarist policy that the British Thatcher government had adopted meant that increases in interest rates would naturally flow through to higher profits for the banks.

Thatcher, together with Chancellor of the Exchequer (Finance Minister) Geoffrey Howe took the view that as the banks were profiting from monetarism they should pay additional tax as a result. However, windfall taxes are highly problematic in terms of defining

Clearly it would be perhaps appropriate to align settings with Australia. An alternative therefore might be to adopt the Australian bank levy.

A 0.6% levy on banks with liabilities over A$100 billion has been in place since 2017 and there have been calls to increase it. If you're aligning the treatment of the big four banks with what their parents are subject to in Australia, then politically you have probably removed one objection to any such surcharge.

Another area which could be considered are the thin capitalisation rules. That is, the level of debt that banks would be allowed to carry and still claim deductions.

The general rule is that if the debt/asset threshold exceeds 60% then interest restrictions are put in place.

There is a lot going on in this space around the world. Last year the OECD’s corporate tax statistics report said that there are now over 100 interest limitation rules in place, which is up from 67 jurisdictions having such rules in 2019.

Obviously, the Government considers there is some scope for tweaking the tax rules, but this is a political matter and ACT leader David Seymour has already put the kibosh on that. Whether that means the Government will not proceed, or that it reaches out to see if it can get cross party support on any proposals, we'll have to wait and see. This is an interesting development which we will watch with some interest.

FamilyBoost scheme changes

The Finance Minister also announced on Monday that there would be changes to the FamilyBoost scheme which gives eligible families a rebate on fees paid to early childhood education centres. Take up has not been anywhere near as high as was expected or promoted when the proposal was made.

In recognition of this, the Government decided to revamp the scheme and has lifted the threshold for maximum eligible income from $45,000 per quarter to $57,286 per quarter. In other words, from $180,000 per annum to $229,000 annual household income.

The amount that can be increased has gone from 25% to 40%, up to a maximum of $1,560 per quarter. There's also a reduction in the abatement rate from 9.75% to 7% for household income over $35,000 per quarter.

The intention is that these changes will come into effect for childhood education costs incurred in the current quarter from 1st July to 30th September onwards. Legislation will come be coming through on this.

As the tireless Craig Renney, Chief Economist for the Council of Trade Unions, has noted, this change is very generous and is weighted towards higher income families.

What about Working for Families?

Looking at the increased abatement thresholds coupled with reduced abatement rate, I do not understand why the Government has done nothing in relation to increasing the abatement threshold for Working for Families, which still remains at $42,700 for total family income.

Although there were changes in this year’s Budget (including an increase in the abatement rate to 28%) this threshold has not been changed since 1st of July 2018, seven years ago now.

The Government is sending mixed messages. Both measures - Working for Families and FamilyBoost - help working families, but it appears only high-end families have the issues of abatements and the impact of high effective marginal tax rates addressed.

There would probably be greater cost involved in lifting thresholds and/or reducing abatement rates for Working for Families, but whoever said politicians would be consistent in their approach?

To me the changes create a weird scenario. But FamilyBoost was a Government election commitment, so it's understandable the Government is trying to make it more accessible.

Inland Revenue releases submissions

At the start of this year there was a lot going on in relation to the not-for-profit sector, with many thinking the Government was looking to change the tax treatment of this sector and in particular the exemption from business taxation for businesses run by charities.

It subsequently backed away from that although the issue of the taxation of mutual transactions of associations, clubs and societies is still under review.

Last Monday (it was a busy old day) Inland Revenue proactively released the submissions it received on the issues paper Taxation and the Not-for-profit Sector it sent out for consultation in February. It received 826 submissions, which is quite a number, and it has published all these submissions where permission has been given. It's also produced a four-page summary of the common themes in the submission.

One was that consultation needed more time, which I totally agree with. Others felt the Government was looking at the wrong end of the issue in that not-for-profits provide a net benefit, not a net cost for the Government, because they save government expenditure.

Another was that the issues paper lacked clarity about what was the problem to be addressed, with many submissions suggesting the focus should be on the bad actors. All good points in my view.

What about the charity business exemption?

On the charity business income exemption, there were differing views as to whether in fact charities had a competitive advantage.

Economists generally agreed with Inland Revenue‘s view that no advantage existed. But other submitters disagreed. There were questions about the complexity of defining the issue at stake, with some submitters skeptical about how much revenue could be raised.

There were also suggestions that maybe a minimum distribution rule could be a more effective policy response.

There was a mixed response on the issue of donor-controlled charities. As usual, some acknowledged there were concerns on this, but others thought again that the existing regime was rigorous enough and any changes would impose increased compliance costs.

On the vexed issue of not-for-profits and friendly society transactions, the view was that these should be removed from the system and member subscription should remain non-taxable.

In relation to a de-minimis tax free threshold “There was near universal support from those that submitted on the mutuality topic that the $1000 income tax deduction was too low and should be increased.”

Overall interesting to see these responses. As noted above, consultation has just closed on the application of the mutuality principle to transactions of associations, clubs and societies. There has been strong pushback on this as well so it will be interesting to see what emerges.

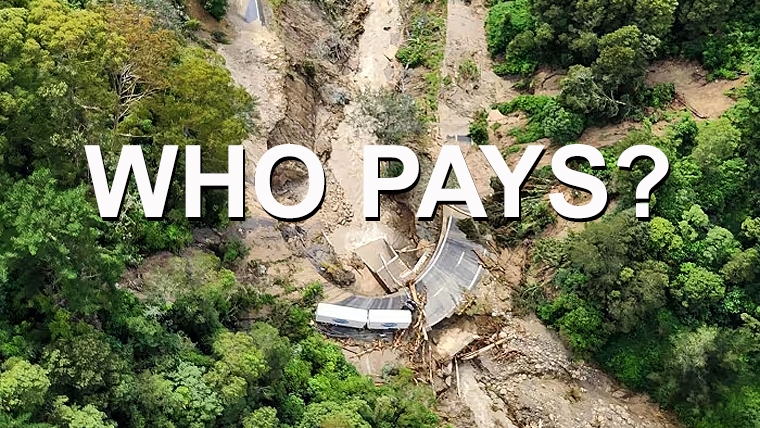

Climate adaptation – who pays?

And finally, this week, on Wednesday the Independent Reference Group on Climate Adaptation released its report, A proposed approach for New Zealand's adaptation framework.

This is a group that's been put together to give the Government some guidance on developing a framework for dealing with climate adaptation. It's a short report, only 16 pages and well worth the read.

The report’s opening paragraphs dive right in:

“The group considers there to be an urgent need to change the way New Zealand adapts to climate change. New Zealand is already experiencing the impacts of climate change, but it is currently underprepared. This is leading to larger and more frequent recovery costs, unmanaged financial strain and disproportionate impacts on some groups.

Climate change will continue to bring substantial financial costs for the country. Failing to act or delaying decisions will not avoid or reduce costs that New Zealand governments, businesses and individuals face.

That's an on the nose and in my view accurate summary of the position we face. As I'm recording this podcast the Nelson/Tasman region is under a state of emergency for yet another storm that is expected to hit in the next few hours. This is just the latest experience of the “impacts of climate change.”

Achieving “a consistent approach”

The report considers that “New Zealand needs a consistent approach to decision making that is well informed about the risks.” To achieve this approach, it suggests there are three key areas which need to change.

Firstly - New Zealanders need to have fair warning about the way natural hazards could impact them, so they can make informed decisions too.

Secondly - New Zealand should take “the broadest interpretation of a ‘beneficiary pays’ approach to funding the increased investment and risk reduction because of climate change. This would mean that those who benefit most from these investments contribute more.”

Finally, people and markets should adjust over time to a change in climate. The adjustment is already happening. Insurers have been raising premiums and making it clear that there are areas where the insurance risk is greater than they are comfortable with.

The question that the report raises is the length of this transition period beyond which “people should not expect buyouts”. In its view

“The Group acknowledges there is no right answer to how long a transition should take. However, the Group considers that a transition period of 20 years would appropriately balance the need to spread costs with creating the right incentives to act.”

Who pays?

However, the report is pretty silent about the meaning and extent of what it refers to as “financial assistance” which, it suggests, does not continue beyond the transition period. Neither of the words ‘tax’ or ‘levy’ appear in the report and in my view, that’s kicking the can down the road.

The report is right to highlight the scale and urgency of climate adaptation, but it should have gone further and said, “we need to prepare for this, we suggest that it's going to need either higher taxation or a climate levy.”

By doing so, the issue comes up for discussion. Instead, it has rather ducked that point.

This has drawn criticism from a climate policy expert, Professor Jonathan Boston, who said phasing out government assistance for climate adaptation and property buyouts would be “morally bankrupt.”

Although he agrees we should not be creating incentives for people to stay in risky areas, he feels that a 20-year transition period is not long enough, and ongoing government support will be needed. I agree with both those points.

The costs of climate change are happening now

The issue of how governments manage rising superannuation and health costs is important. But I think the more immediate financial impact we have to address is climate adaptation.

And unfortunately this report, although it clearly spells out the risks that we're facing and the need to develop a framework to respond, ducks the key question of “who's going to pay for this, and how do we finance that transition?”

As I have said repeatedly, this is going to involve some form of tax increase or specific levy.

The cost of climate adaptation is an issue where we really do need all the politicians to put party politics aside and address the longer-term issues - that climate adaptation will involve huge costs which presently falls on local councils who are in no position to fund the burden.

It is going to require central government support, in the form of specific tax or levy.

And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day and best wishes to everyone in Nelson/Tasman, or anywhere else affected by the bad weather.

5 Comments

Another pile of economic garbage which is considered smart thinking in NZ. The government can easily and without any fiscal or monetary problem fully fund mitigation and restoration for disaster relief at any time now or in the future. Just as it has always done in the past.

In WW2 did the government concern itself with how it was going to pay for the defense costs or was it more concerned with how to protect the country from invasion and disaster? There were no fiscal or monetary constraints because in the real world they don't exist.

The article above and the many similar to it are based on complete economic fabrications and flat out lies.

No, the Government cannot 'easily fund' indefinitely.

As Luxon has articulated (not that I regard him as being above average).

The problem is that money is underwritten by energy, and by resources to apply that energy to. We are approaching the limits to growth in both, if not over them already.

Funding was really 'allocation energy and resources'.

And those have hard limits.

Keynes,

One of the defining features of MMT is its insistence that as long as government's debt is denominated in its own currency, there is no upper limit on the state's monetary borrowing. In other words, public debt is irrelevant; a country's central bank can always avoid default by printing more money.

It's a nice theory, but runs into the real world, as for example, the UK found out in 1976 when Dennis Healey, the Chancellor had to request a loan from the IMF. The country was experiencing high inflation and a substantial balance of payments deficit. Investors lost confidence in Sterling and the pound fell sharply. Why not just print more money? Quite simply. as Gilt yields rose above 15%, the Treasury ran out of buyers.

Clinton ran into the same problem in 1993. I could produce other examples. The issue is confidence. With a fiat currency, confidence is what keeps the ship afloat.

Owners enjoy the amenity of adjacent beach, river, or other location amenity. That comes with associated risks. Losses are either covered by the owner in a user pays model with insurance premiums set to manage risk, or socialised over the rest of NZ via tax.

The foolish bag holders are normally the..... bag holders

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.