By Andre Castaing, David Crow and Sharon Zollner

Summary

- Recent rises in global interest rates have driven local long-term rates higher too. The direct impact of long-term rates on economic activity is less in New Zealand than in the US, but that’s not to suggest they don’t matter.

- Rising US rates have strengthened the USD and caused NZD to depreciate, loosening New Zealand financial conditions.

- On the other hand, higher long-term rates slow global growth, which will negatively impact the New Zealand economy. In addition, sharp rises in long-term rates may increase global financial stability risks.

Higher long-term rates, same OCR

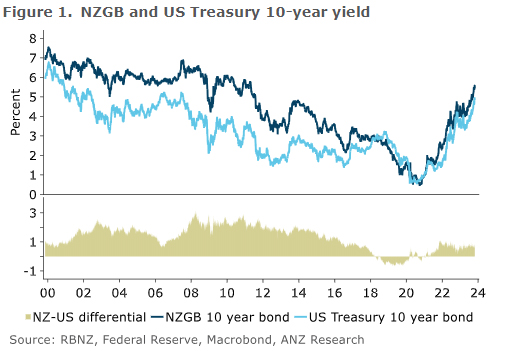

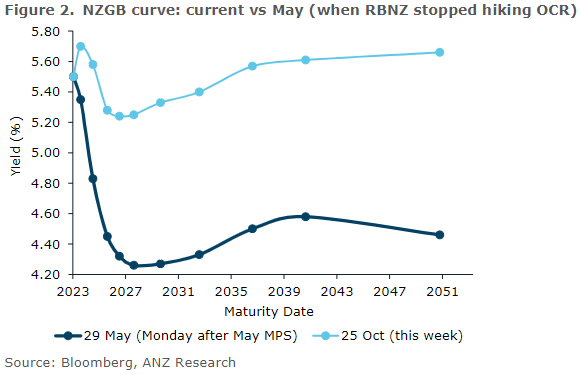

Since the RBNZ called a top in the OCR in May, long-term NZGB bond yields have continued to push higher (figure 1), led by moves in US bonds. The bellwether 10-year Treasury bond yield pushed through 5% for the first time since 2007 this week. There has not been a singular clear catalyst for US long-term rates rising. The Fed’s “high for longer” rhetoric, oil and other medium-term inflation risks, rising term premia, lower Treasury purchases by China, and increased bond supply from quantitative tightening and US fiscal deficits have all played a role.

Direct effects of long-term rate rises on the NZ economy

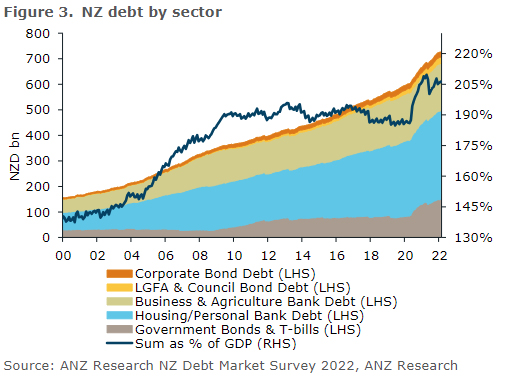

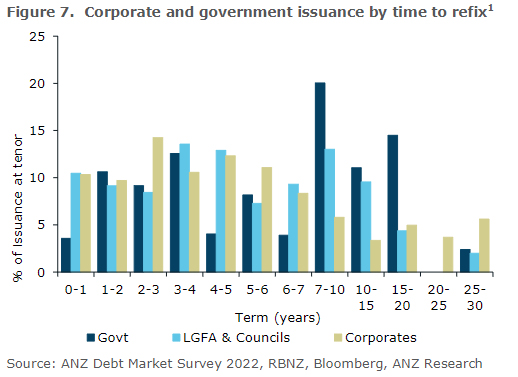

When considering the impact of higher long-term interest rates on the New Zealand economy, it is useful to split the discussion into the three main groups of borrowers: households, corporates, and local and central government, all of which have different shares of issuance (figure 3).

Households

In the US, homeowners typically pay a mortgage rate that is fixed for up to 30 years, with the right to repay early without penalty. This leaves homeowners in an enviable position both when interest rates rise (they have the option to stay fixed and ride the cycle out, as long as they don’t move house), and when interest rates fall (they have the option to repay and refinance at a lower rate). Importantly, though, new mortgage borrowers are fully exposed, meaning that just like in other countries, new home buying and building as well as durables purchases tends to reduce as mortgage rates rise, dampening economic activity and inflation.

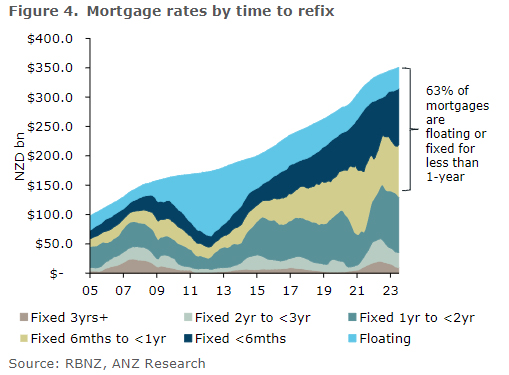

Contrast that to New Zealand, where borrowers generally have the ability to fix out to a maximum of five years, and as figure 4 shows, tend to fix their mortgages for only one or two years. That leaves existing borrowers far more exposed to short-term rates, and less exposed to long-term rates.

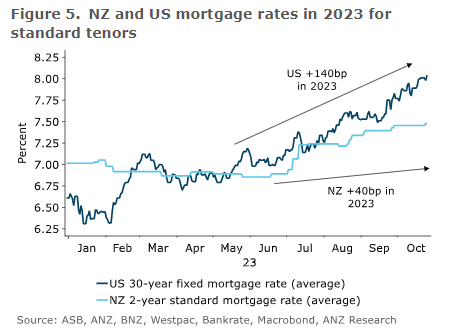

And as figure 5 shows, New Zealand short-term mortgage rates have increased by far less than US long-term mortgage rates this year. Over 2023, the benchmark wholesale rate for US 30-year mortgages has risen around 1.4% points, more than the rise in the US federal funds rate (the equivalent of the RBNZ’s OCR). US policy makers are counting this as extra contractionary pressure that reduces the need for further policy rate hikes. For example, Mary Daly, president of the San Francisco Fed, indicated that the rise in long-term yields to date is roughly equivalent to one 25bp hike in the US.

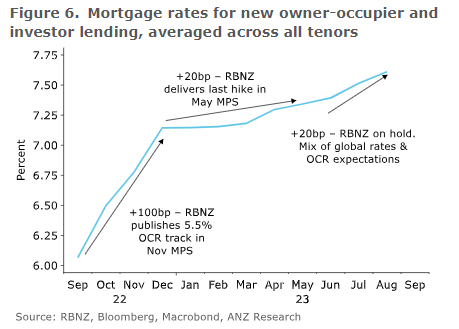

On the other hand, New Zealand’s mortgage rates for 2-year fixings have had much more moderate increases over 2023 (figure 5), with moves primarily reflecting evolving expectations of where the OCR will average over the next two years. Quantifying precise contributions and proving causality is difficult, particularly when yield curves are moving in similar ways, but changes in US long-term rates have almost certainly contributed to recent rises in New Zealand swap rates and by extension mortgage rates. Since the May MPS, the average mortgage rate paid by owner occupiers and property investors on new lending (including those rolling over fixed terms) has risen by about 20bp (figure 6), which has occurred in the absence of OCR increases.

Corporates

Another key difference between New Zealand and the US is that New Zealand does not have such sophisticated or liquid corporate public debt markets, with the majority of lending to New Zealand companies occurring through banks at shorter tenors (figure 3). That tendency is especially evident in the SME sector, where in some cases, businesses are funded by mortgages over founders’ or owners’ family homes. Therefore, changes in long-term rates are unlikely to affect the hurdle rates (how much a project needs to return to break even) for new corporate investments.

Government

There is a direct cost to taxpayers and ratepayers from the lift in long-term yields, given that as figure 6 shows, both central and local government spread their borrowing across a range of tenors out to 20 years or even longer, including an upcoming 2054 bond syndication.

But central government has deep pockets: the higher debt-servicing costs will essentially be rolled into future borrowing requirements, rather than requiring the Government to slash its spending immediately. The impact is real, but with debt levels that are still low in a global comparison, there isn’t a big negative immediate impact via this channel. For example, according to the IMF, New Zealand’s net debt was 20% of GDP at the end of 2022, compared to 32% for Australia, 92% for the UK and 94% for the US. Net debt is expected to grow, but at 20% of GDP, even with 5% coupon payments, the total interest cost is only around 1% of GDP, compared to multiples of that for other countries.

Some councils, on the other hand, are very leveraged and will have less flexibility to look through this rise in funding costs. Local governments have fewer funding avenues than central government and the rapid rise in debt-servicing costs may require higher property rates, fewer local services or further postponements of infrastructure maintenance, especially in regions that already have high levels of debt. This may be a different reaction to central government, who face less trade-offs and constraints in terms of issuing more government bonds to cover the shortfall. However, the incoming Government’s appetite to increase issuance beyond the Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Update (PREFU) projection remains to be seen, as do any changes to the funding model for local government.

Overall

The short-term fixings in New Zealand markets, especially for mortgages and bank business lending, means that the direct effects of the rise in long-term rates are likely to be much smaller for the RBNZ than the 25bp or so ‘free’ tightening for the Federal Reserve, since a limited amount of economic activity is priced off these long-term rates.

Indirect effects of long-term rate rises on NZ

While direct effects may be limited, the New Zealand economy isn’t immune to higher long-term US rates slowing our economic activity through weaker demand for our exports. We would expect this effect to be larger than the direct channel, but still small in terms of the overall economic picture. This is because the Fed is characterising these increases in term rates as roughly equivalent to a 25bp hike in the fed funds rate that otherwise may have been required. To the extent the Fed is able to trade off one end of the yield curve with the other, direct impacts on the US economy should be limited. There may be some nuanced impacts on the monetary policy settings for other trading partners in Asia, but they are beyond the scope of this note.

Lifts in US rates at either end of the yield curve can impact the NZD. If moves in the NZ yield curve don’t roughly keep pace (by OCR hikes at the short tenors or moves in bond yields at the long tenors), the decreased relative attractiveness of NZ rates can see the NZD materially depreciate – one of the challenges of being a small open economy. In practice the impact isn’t precise nor predictable, given everything else that influences both currencies and investors’ decisions about where to park their money.

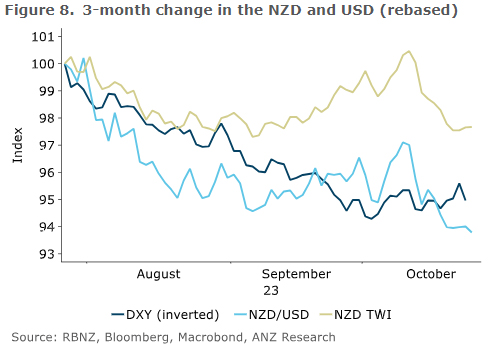

Recent flows have caused NZGB yields to rise by a similar amount compared to their US Treasury counterparts, meaning long-term rates’ effect on the NZD will have been somewhat muted. The lack of a premium for short-term rates won’t be doing much to make NZ a popular investment destination (given New Zealand’s policy rate has tended to sit above that of the Fed on average over history), but neither will the trade deficit nor commodity risk.

Overall, while the NZD is an important part of New Zealand monetary conditions (via imported inflation and exporter incomes), long-end yield differentials are not likely to have directly caused much of the recent depreciation in NZD, given New Zealand yields have broadly kept pace (figure 1, page 1).

However, they likely have indirectly contributed to the depreciation in the NZD (figure 8, over) via risk-off sentiment driving continued strength in DXY (the USD trade-weighted index). That said, this sentiment could reverse quite rapidly and has not caused material weakness in most NZD crosses, so may not have a large effect on NZ economic activity.

Financial stability

Higher US bond yields are generally bad for equities and other asset prices, so will help cool global growth via that channel too. But could it spill over into something uglier?

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank earlier this year provided dramatic examples of what can happen when financial institutions manage interest rate risk poorly. However, it’s not unreasonable to think that they are outliers; financial regulation is much stricter than it was pre-GFC. There are more safeguards against contagion between institutions and these recent collapses will have given risk managers a wake-up call on what can go wrong if they are not well hedged against rises in long-term rates. It’s not just banks that are in a better position than pre-GFC; US households are in much better shape too, in terms of their leverage.

Nonetheless, we are nowhere near the end of the process of finding out the consequences of a widespread misperception that central banks would keep rates super-low for many years. Banks, fund managers, governments, businesses, individuals and even central banks have been caught by surprise and will have made decisions that they regret with the benefit of hindsight. Given the size and speed of the global rates sell-off it would not be unsurprising if there’s more trouble to come.

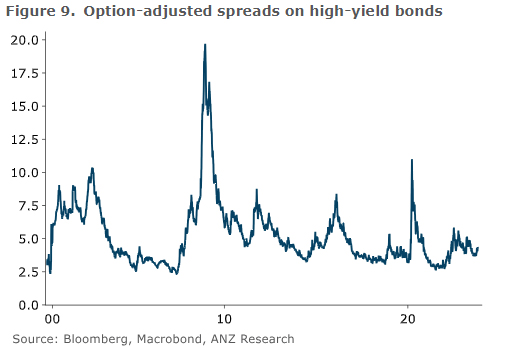

Among the myriad of potential sources of stress two stand out to us – US junk bond markets and private capital markets.

Junk bond markets have not been subjected to a period of sustained heighted credit risk and defaults since the Global Financial Crisis (figure 8), meaning there are many marginal firms that are still limping on. Some failures are inevitable, and it could trigger a broader repricing of risk of all kinds, seeing the borrowing costs of NZ Inc. lift independently of the outlook for monetary or fiscal policy.

Second, private capital markets grew exponentially during the 2010s as investors took on more risk in an effort to achieve decent returns in a world of near-zero policy rates. The sector is opaque and minimally regulated. Private assets have low liquidity, so many investors have decreased their total portfolio liquidity. That increases the risk of capital calls that could require destabilising fire sales of liquid assets like bonds and equities. It’s very difficult to gauge the extent of this risk, but whether it’s low or high, sharp increases in US bond yields (the asset against which all other risk is priced) will have raised it.

Financial wobbles are by their nature unforecastable in terms of both timing and magnitude and central banks can’t set policy for things that may or may not happen; they have to play the cards that are in front of them. Nonetheless, most market watchers would say long-term rates are more interesting than the short-term ones at present. It’ll be interesting to see what the RBNZ is looking at most closely in next Wednesday’s Financial Stability Review (FSR) and press conference.

Summing up

We don’t think the rise in global term rates will have a large direct effect on New Zealand’s economic activity or RBNZ OCR decisions given how little private sector borrowing occurs at tenors beyond three years. But to the extent they slow US and global growth, they matter.

On the other hand, it’s probably contributed to downward pressure on the NZD, which represents an easing of monetary conditions, all else equal. We don’t think the direct effect of interest rate differentials are a big driver currently, but the risk-off vibe associated with the sharp increases will have had an impact.

The cost to the taxpayer of higher bond yields is also real, of course, but the spending impacts of that will be spread over many years, for central government at least. The impacts on local government could be greater, but this sector is small.

Finally, rapid rises in long-term rate do increase the likelihood of a severe tail risk event emerging in global financial markets, though this risk is very difficult to quantify, and household and firm balance sheets are in many instances in better shape than the period preceding the Global Financial Crisis. The RBNZ can’t set policy based on potential low probability, high-impact events, but will keep a watchful eye out for signs of stress emerging.

[1] This chart excludes agricultural and business lending by banks (around a quarter of total lending), due to data constraints on tenor. Typically these loans are floating or fixed for a short period. Refixing times tend to be fairly stable from year-to-year, but may have changed somewhat since our 2022 survey.

This article is here with permission. The original is here. The authors are economists at ANZ NZ.

7 Comments

The cost to the taxpayer of higher bond yields is also real, of course, but the spending impacts of that will be spread over many years, for central government at least.

Hi ANZ. Just letting you know that NZ Govt has about $160 billion of outstanding bonds with fixed coupon rates and around $20 billion of index-linked bonds (of which Govt / RBNZ owns half!) The weighted average interest rate on those fixed rate bonds is currently 2.44% so the debt is deflating quickly. Also worth noting that Govt / RBNZ owns more than $50 billion of those bonds and is happily paying itself interest for giggles.

Current forecasts for bond issuance (and the end of maturing bonds) might push the weighted average yield up to around 3% over the next couple of years. So, not sure how 'real' the impact on the taxpayer is - particularly given that the private sector is the recipient of the interest that Govt pay out. Govt debt = private sector assets remember.

Where the Govt is exposed to higher rates is on the $53 billion of settlement account balances held at RBNZ. ANZ own around half of those. Reserve balances are basically floating rate Govt debt with interest set at the current OCR. A glorious $8 million of interest per day flows from the Crown to the banks at the moment, so that's $4 million per day to ANZ. Kerching! No wonder your economists are in the news everyday calling for a higher OCR.

If you cared about the cost of interest to the taxpayer, you might want to suggest that RBNZ stop paying interest on some of those settlement account balances - like the ECB did in July.

The reason why bond yields are rising in USA is because the US Government is running large fiscal deficits. Treasury bonds are not safe anymore and a risk premium is being demanded.

I would like to see an article around how NZ would be impacted based on a 30yr UST of 7%.

I would suggest 10% mortgages are coming in 2024. I would also suggest the NZD will fall to 40c US as the USD rises. If our rates do not rise we will see very high imported inflation.

Many people in NZ will be financially destroyed especially those that borrowed at the Dec 2021 housing peak.

Oh and watch out for Japan. A currency crisis is imminent, they will have to sell their US treasury holdings to defend the Yen and this could destabilize the entire US Debt market with worldwide implications

Good post QG, certainly a lot more eloquent than "10% guaranteed" repeated ad nauseum.

You're making a classic mistake there in assuming that bond prices are significantly affected by deficit levels.

Janet Yellen is bang on right on this one - bond yields are rising because traders think that interest rates are going to be higher for longer. This is not a supply and demand thing - not least because deficit spending creates the reserve balances that are used to buy bonds.

If interest rates nudge higher to 10%, I would think that the share of home buyers might shift, less first home buyers, less NZ'ers buying, and a larger share of purchases of property by new immigrants, their money will be going a long way if the NZD keeps falling. Inventory will remain tight, and cash buyers will fight it out for the few properties available pushing prices ever higher. Inflation will stay elevated, rents higher, and investors still sit on the sidelines.

I think that's the best way out.

First thing we have to agree and accept is that our mortgage debt(private debt) is unsustainable.

To reduce the private debt government has to run deficit and build a sustainable economy or our trade deficit has to become positive . Bringing skilled migrants who can bring money along with them will offset those trade deficit.

Thankyou so much.

What a fantastic article this is!!!

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.