By Peter Drennan*

When the High Court placed six Chance Voight (CVI) entities into interim liquidation on 9 December 2025, many observers noted the procedural similarities to the Du Val collapse of 2024. But as someone tracking these matters closely, I think the more interesting question isn't whether the cases look similar, it's whether Chance Voight will ultimately follow Du Val into statutory management, one of the most rarely-deployed weapons in New Zealand's regulatory arsenal.

Having spent time mapping the corporate structure and reviewing the land title records, I'm increasingly persuaded that two factors may push this matter toward statutory management: the sheer complexity of the corporate web, and the extent of related-party dealings visible even in the public record.

Have you heard of a guy named Bernie Whimp?

A question I asked a Christchurch lawyer with a recently issued SuperGold card. "You mean Bernard Terence Whimp," he replied with a smile, before noting that we only recall middle names when someone reaches a certain level of notoriety.

It seems everyone in the Christchurch business community knows of Whimp's schemes. Of the various people I've chatted to about him, the most positive take I heard was that he's like a catfish that makes our regulatory regime swim faster. Indeed, his activities prompted two legislative changes.

The first closed a loophole he exploited while banned as a company director: he structured his operations through limited partnerships with himself as general partner—a role not then covered by the director prohibition. The second addressed his "low-ball" share schemes, in which he made unsolicited offers to retail investors at prices below market value, or with payment deferred over 10 years (which significantly reduced the net present value of apparently generous offers). Parliament closed the unsolicited offers loophole in December 2012 and the limited partnership loophole in September 2014.

For a more detailed timeline of Whimp's prior history, see the appendix at the end of this article.

Chance Voight

So now to 2021. Whimp launches Chance Voight, another of the CVI entities (Chance Voight Investment Partners Limited) appears to have been registered in 2018, the chancevoight.com domain shows active content from 2021.

With Chance Voight, Whimp leaned into his prior experience. The Chance Voight website explains the unique opportunity for investors:

“I’m establishing CVI Partners as a specialist equity/securities investment firm, buying and selling stakes in worth-while companies whose shares are listed on the ASX, buying dollars for 50 cents, with the aim of compounding investment capital at 20% pa or better, over multiple years.”

It appears that Chance Voight was quite successful at raising capital, with a reported $45.3 million raised since 2021.

FMA investigation and interim liquidation of Chance Voight

Much could be written on what exactly was offered to investors, and the line between bold marketing and illegal activity, but let us fast forward to the present. The Financial Markets Authority (FMA) has been investigating Christchurch-based Chance Voight Investment Corporation (CVI)and its associated entities, a group that appears to comprise around 27 companies and limited partnerships, for several months. The FMA issued four compulsory information requests under section 25 of the FMA Act. According to the Court, it was "not satisfied with the responses."

On 9 December 2025, Associate Judge Lester placed six entities into interim liquidation, while Justice Harland simultaneously granted asset preservation orders against Bernard Whimp and Hanmer Equities Ltd (a CVI subsidiary). PWC were appointed as interim liquidators.

Three days later, the defendants tried to stay the liquidation process—essentially asking the Court to prevent public notification and pause the interim liquidators' work. That application was declined. As Judge Lester noted, the directors "were not able to provide... an explanation to address the concerns raised by the FMA."

The interim liquidators must now deliver their initial report to the Court by 26 January 2026.

The Du Val playbook

In August 2024, Du Val Group followed a similar trajectory: FMA concern, court-ordered interim receivership, asset preservation orders, an interim report to the Court, and then, just 19 days after the initial court orders, the Governor-General (on ministerial advice following an FMA recommendation) placed Du Val corporations into statutory management via Order in Council.

Statutory management is a different beast entirely. Under the Corporations (Investigation and Management) Act 1989, it essentially removes a corporate group from normal insolvency processes and hands control to statutory managers with extraordinary powers. The FMA can recommend this path when either:

- The corporation is or may be operating fraudulently or recklessly, or

- It's desirable for creditor/public protection and those interests cannot be adequately protected under the Companies Act 1993 or in any other lawful way

That second limb is crucial. It's the "ordinary law is inadequate" test.

What made Du Val a statutory management case?

The Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (MBIE) cabinet materials released under proactive disclosure requirements are illuminating here. The interim receivers' report (restricted from publication) identified three key concerns that drove the statutory management recommendation:

- Accounting irregularities and related-party balances requiring investigation and recoverability analysis

- Complex corporate structure making it difficult to treat entities separately

- Risk from multiple competing insolvency processes, the view that orthodox liquidation/receivership wouldn't adequately preserve investor interests

There was also a policy rationale: statutory management suspends existing insolvency processes so that one team can deal with the affairs holistically, rather than having multiple liquidators, receivers, and creditors fighting over the carcass in parallel proceedings.

Du Val had approximately $250 million in external liabilities and around 120 investors. The scale, complexity, and interconnection of the group made statutory management the preferred tool.

Red flag #1: The complexity of the corporate web

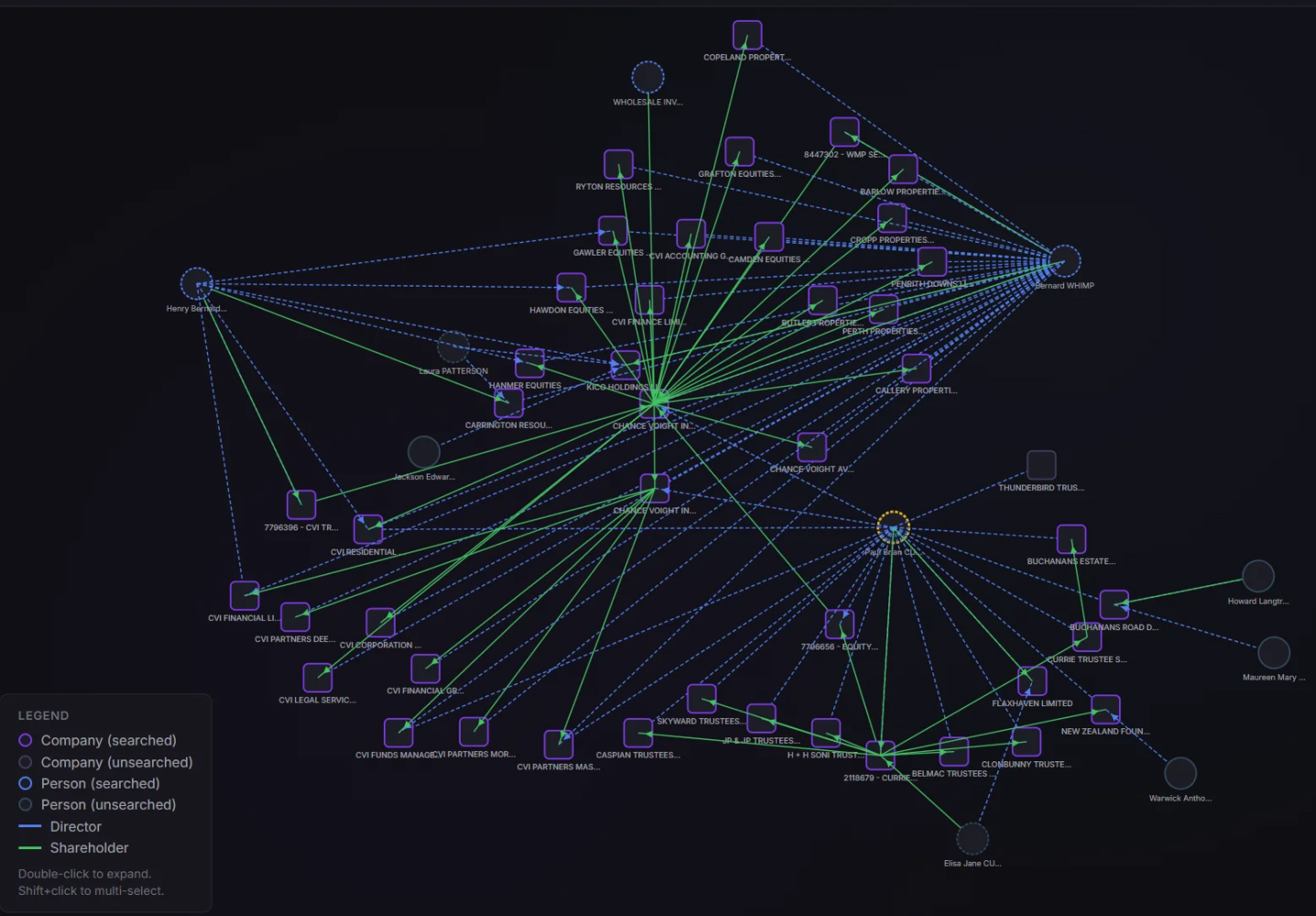

I've created a network graph showing the entities connected to Chance Voight through director and shareholder relationships. I'll be honest: I don't expect readers to interpret this diagram. But that's rather the point. If a web of corporate structure looks like it was created by a gang of spiders hopped up on methamphetamine, that’s a problem for standard insolvency processes.

The purple boxes represent companies. The green lines show shareholder relationships. The blue dashed lines show director connections. The CVI network is complex, but here's the thing: this map only shows registered companies. It doesn't include limited partnerships or trust structures, which are notoriously opaque by design. The court documents reference approximately 27 entities in the wider group. The actual beneficial ownership picture is almost certainly more complex still.

Why does this matter for statutory management? Three reasons:

First, complex webs make normal insolvency processes less efficient. When you have multiple entities with intercompany loans, cross-guarantees, and shared assets, unwinding each company separately becomes extraordinarily difficult. Which entity actually owns what? Where did investor money go? Whose creditors have priority over which assets? These questions become exponentially harder when you're trying to answer them across dozens of related entities.

Second, complexity increases the scope for fraud and misappropriation. The more entities in a structure, the more opportunities for funds to be moved around in ways that benefit insiders at the expense of investors. Money that enters one fund can exit through a loan to a related party holding company, which then pays it out as management fees or dividends to another entity. Tracing these flows requires looking at the whole picture, not individual pieces.

Third, complexity increases the risk of competing insolvency processes. If different CVI funds end up with different liquidators, you get multiple professionals all trying to recover from the same pool of assets, all incurring fees, all potentially litigating against each other over priority. That was a specific concern flagged in the Du Val materials—and it applies here with force.

The Court noted that Chance Voight used a "single bank account" for "all group transactions" since November 2024, with investor monies apparently being "pooled" into the holding company. Its hard to determine whether that is speaking just to the entities placed into interim liquidation, or also includes other group companies. But that language suggests the economic reality is one integrated enterprise, regardless of how many separate legal entities appear on paper.

Red flag #2: The related party transactions

The MBIE cabinet materials on Du Val specifically flagged "related party balances" as requiring investigation and recoverability analysis. Based on what's visible in the public record, Chance Voight appears to have similar issues, and perhaps more extensive ones.

Maria Slade's reporting for BusinessDesk has referenced a former employee who noted that an entity may have made related party loans of $6 million to $6.5 million, with questions raised about whether these were properly documented. That alone would be a significant concern. But even without access to internal records, the land titles tell a revealing story.

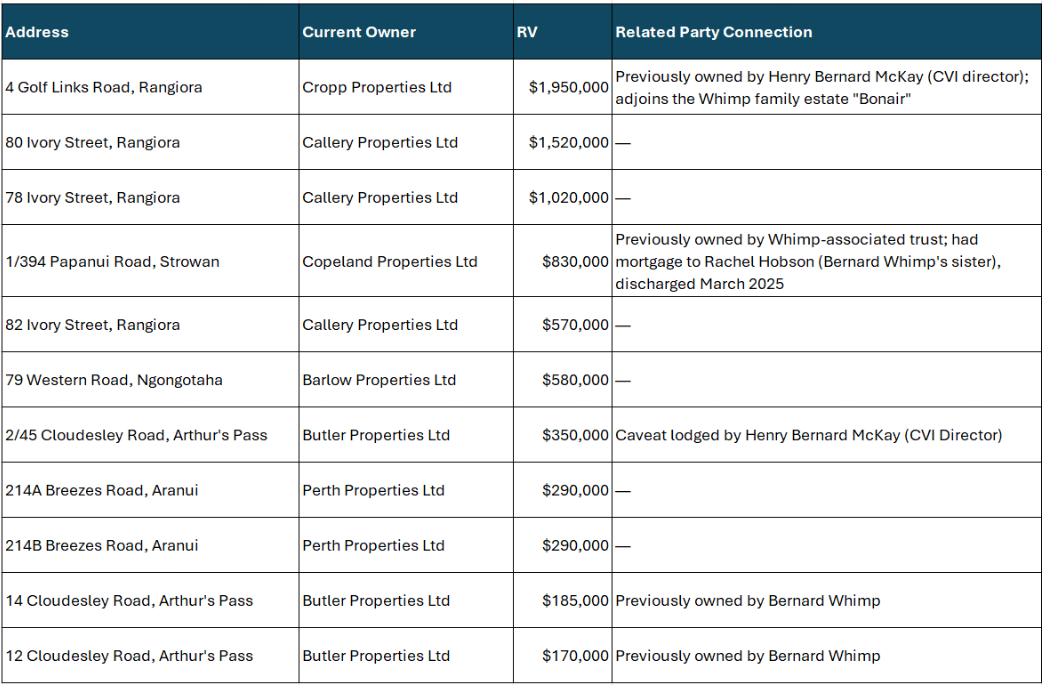

I've identified properties that are subject to registered mortgages held by two of the CVI funds—CVI Partners Mortgage Fund Limited and CVI Partners Mortgage Income Fund Limited. These funds hold mortgages over various other CVI subsidiaries. All properties in the table below appear to be owned by CVI subsidiaries, with mortgages to the CVI funds.

A few observations jump out.

The total rateable value is around $8 million. The court documents reference investor deposits of approximately $45.3 million since 2021. Even allowing for other assets not captured here, the gap between what investors put in and what appears to be securing their investments is a concern. However to be fair to Whimp, CVI claims to have been investing in shares, so significant equity positions may be held in addition to these mortgages.

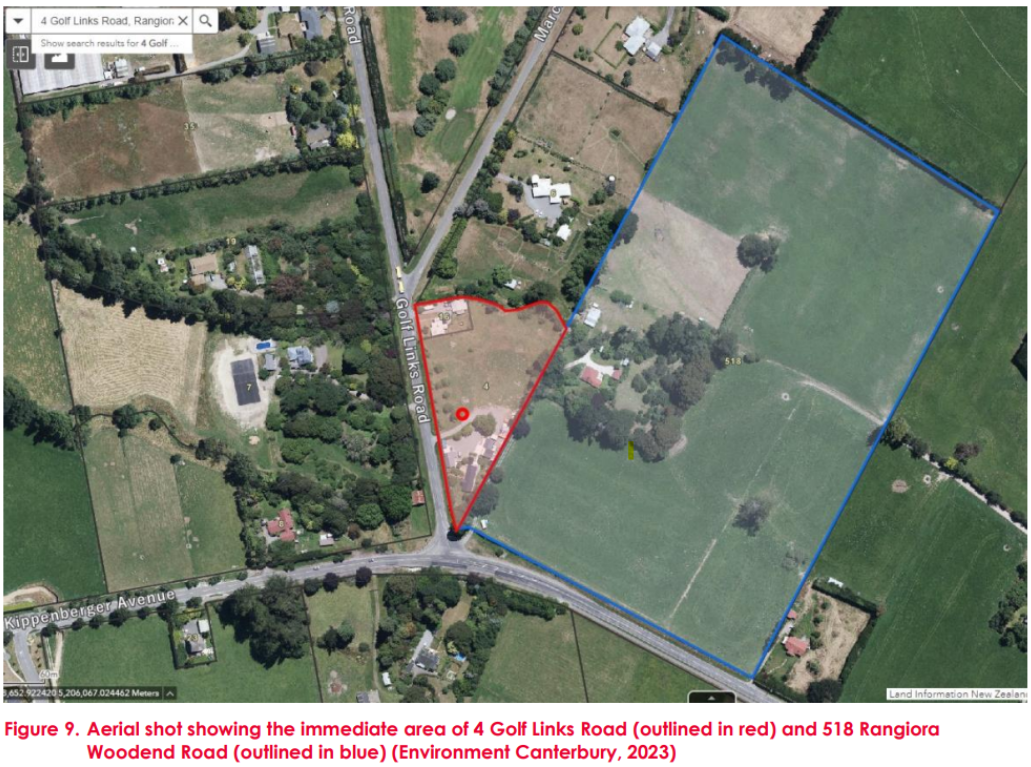

Multiple properties have clear related-party histories. Properties at 12 and 14 Cloudesley Road were previously owned by Bernard Whimp before ending up with Butler Properties Limited (who then mortgages them to CVI entities). The Papanui Road property passed through a Whimp-associated trust and at one point had a mortgage to Whimp's sister, Rachel Hobson. The Golf Links Road property (the most valuable in the portfolio), was previously owned by Henry Bernard McKay (former director of various CVI entities) and sits directly adjacent to "Bonair," the Whimp family property at 518 Rangiora Woodend Road. Various records indicate that Bernard Whimp and his sister have been seeking rezoning of the Bonair land to allow redevelopment.

And there's more that isn't in this table. Consider 54 Cloudesley Road, Arthur's Pass. That property was once owned by Bernard Whimp, later sold to a Chance Voight subsidiary, then in early 2025 was sold back to Bernard Whimp with a new mortgage registered to his sister. That transaction pattern raises obvious questions about whether investor funds were being used to benefit insiders. And with a registered mortgage now to Bernard Whimp's sister, this would be a difficult transaction to unwind for a liquidator given the relatively low value of the property.

I want to be clear: these are just examples based on public records. The interim liquidators will be examining internal accounting, bank statements, and transaction records that aren't visible to outside observers. But just based on what we can see from (Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) records, the related-party transactions are striking.

What this means for statutory management

The Du Val experience provides a clear template. When the MBIE materials explained why statutory management was appropriate, they emphasised:

- Accounting irregularities and related-party balances requiring investigation

- Complex corporate structure making it difficult to treat entities separately

- Risk that multiple competing insolvency processes would harm investors

Based on the public record, Chance Voight likely ticks the first two boxes, and possibly the third.

The corporate structure is demonstrably complex, dozens of entities linked through overlapping director and shareholder relationships, with trust and limited partnership structures adding further opacity. The fund pooling and single bank account usage described in the court judgments suggests economic integration that the legal structure obscures.

The related-party connections are extensive in the property record. Properties securing investor mortgages have histories involving Whimp, his sister, his associates, and connected trusts. Former employees have raised questions about undocumented related-party loans. Transaction patterns visible in land titles show assets moving between Whimp personally and group entities in ways that warrant scrutiny, and with significant scope for direct personal benefit for Bernard Whimp, Henry McKay, and other Whimp family interests.

Is there a risk of competing insolvency processes? This is uncertain, the property holding companies are all subsidiaries of CVI, so could be placed into liquidation. While there are examples of competing mortgages, that particular issue seems less of a concern than the Du Val case where significant financing was obtained from third party lenders for developments. So on this point the case for statutory management could fail, with a wider court ordered liquidation with pooling orders preferred.

The 26 January inflection point

The interim liquidators' report, due 26 January 2026, will be decisive. If their findings mirror the pattern I've outlined here, complex structure, related-party entanglement, assets of uncertain value or provenance, and a determination that ordinary insolvency processes can't deliver an orderly outcome, expect the FMA to recommend statutory management.

Statutory management is a controversial tool

My colleague Damien Grant, writing in Stuff, has expressed deep scepticism about statutory management as a tool—a view perhaps unsurprising from a libertarian who has spent his career in insolvency and understands the power conveyed by statutory management. While I share concerns about a regime that hands immense power to for-profit insolvency practitioners, I also see value in the mere spectre of statutory management serving as a check on repeat offenders who weaponise corporate complexity to the detriment of investors and the broader system.

The Du Val appointment was made by Commerce Minister Andrew Bayly, and it remains to be seen whether this reflects a particular ministerial temperament or signals a broader shift in the state's willingness to deploy this power. If Chance Voight follows the same path, we may have our answer.

Bernard Terence Whimp: Sourced Timeline (1998–2021)

1998 — Adjudicated bankrupt. (NZ Herald)

2001 — Bankruptcy discharged after reaching agreement with creditors. (NZ Herald)

December 2001 — Securities Commission prohibited the offer document for "Rosetta Terraces Contributory Mortgage," a scheme offered by General Mortgage, saying it was likely to mislead investors about the nature, type and level of risk involved. (NZ Herald)

June 2003 — Securities Commission ordered General Mortgage to cease acting as a contributory mortgage broker. A High Court affidavit identified Whimp as General Mortgage's "controlling manager." (NZ Herald)

30 October 2006 — Deputy Registrar of Companies prohibited Whimp from being a director or promoter of, or being involved directly or indirectly in the management of, any company for four years (to 30 October 2010) under s385 Companies Act 1993. (New Zealand Gazette)

September 2007 — A second, five-year director ban took effect (to September 2012) under s382 Companies Act 1993, triggered automatically upon conviction for offences connected with company management. (NZ Herald)

By October 2008 — Whimp had been convicted of burglary, removing records of a company in liquidation, and failing to supply records to a liquidator under the Companies Act. (Courts of New Zealand)

4 February 2009 — Supreme Court dismissed Whimp's application for leave to appeal his convictions. (Courts of New Zealand)

2010–2011 — While still banned from acting as a company director, Whimp operated through limited partnerships to make a series of "low-ball" unsolicited offers to shareholders in major listed companies including Vector, Contact Energy, TrustPower, Fletcher Building, Guinness Peat Group, DNZ Property Fund, and SkyCity. Some offers appeared above market price but with payment deferred over 10 years, significantly reducing net present value. (NZ Herald; FMA)

May 2011 — The High Court, on application from the Securities Commission/FMA, ordered the cancellation of share sale agreements, the return of shares to original holders, and made orders preventing Whimp from making any further offers of this kind. The FMA issued a public warning: "Offers from Mr Bernard Whimp may not be in your best interests." The FMA also issued a Warning Disclosure Order under s49 of the FMA Act 2011, requiring any future unsolicited offers from Whimp or associated entities to prominently display the FMA warning. This order binds Whimp and any company or partnership he may form in the future; non-compliance carries a penalty of up to $300,000. The warning remains live on the FMA website today. (NZ Herald; FMA Warning; FMA Media Release)

2021 — Whimp launched Chance Voight Investment Partners

Note: This analysis is based on publicly available court decisions, FMA releases, MBIE proactive disclosure materials, Companies Office records, and LINZ title data. It does not constitute legal or financial advice.

*Peter Drennan is Christchurch Manager at Waterstone Insolvency. This article first ran here and is used with permission.

9 Comments

Is it another red flag when the principal promotes themselves with a helicopter photo ?

Yes.

Could suggest a coat of arms emblazoned on it too - a screwdriver coiled in a snake.

Great (well researched article.

Wow. Smells like the only goodness to come out of this will be tightening legislation to close loopholes. Another names joins my "never do any business with" list.

Now this is journalism.

Less woke nonsense, and more of this real-world stuff.

Great read.

You have to ask where any auditors were in this process.

Also need to ask what is the source, calibre and whereabouts of the $45 mill or so capital raised.

It always amazes me how people can give money to invest to a crook like Bernard Whimp and others. Can they not use google? Or is it just greed and financial ignorance.

Either way it's sad. And there will always be people like Whimp only too keen to separate the gullible from their money.

CVI were actively involved in bowls sponsorship, thus targeting cashed up older folk.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.