By Vitor Gaspar, Marcos Poplawski-Ribeiro, Jiae Yoo*

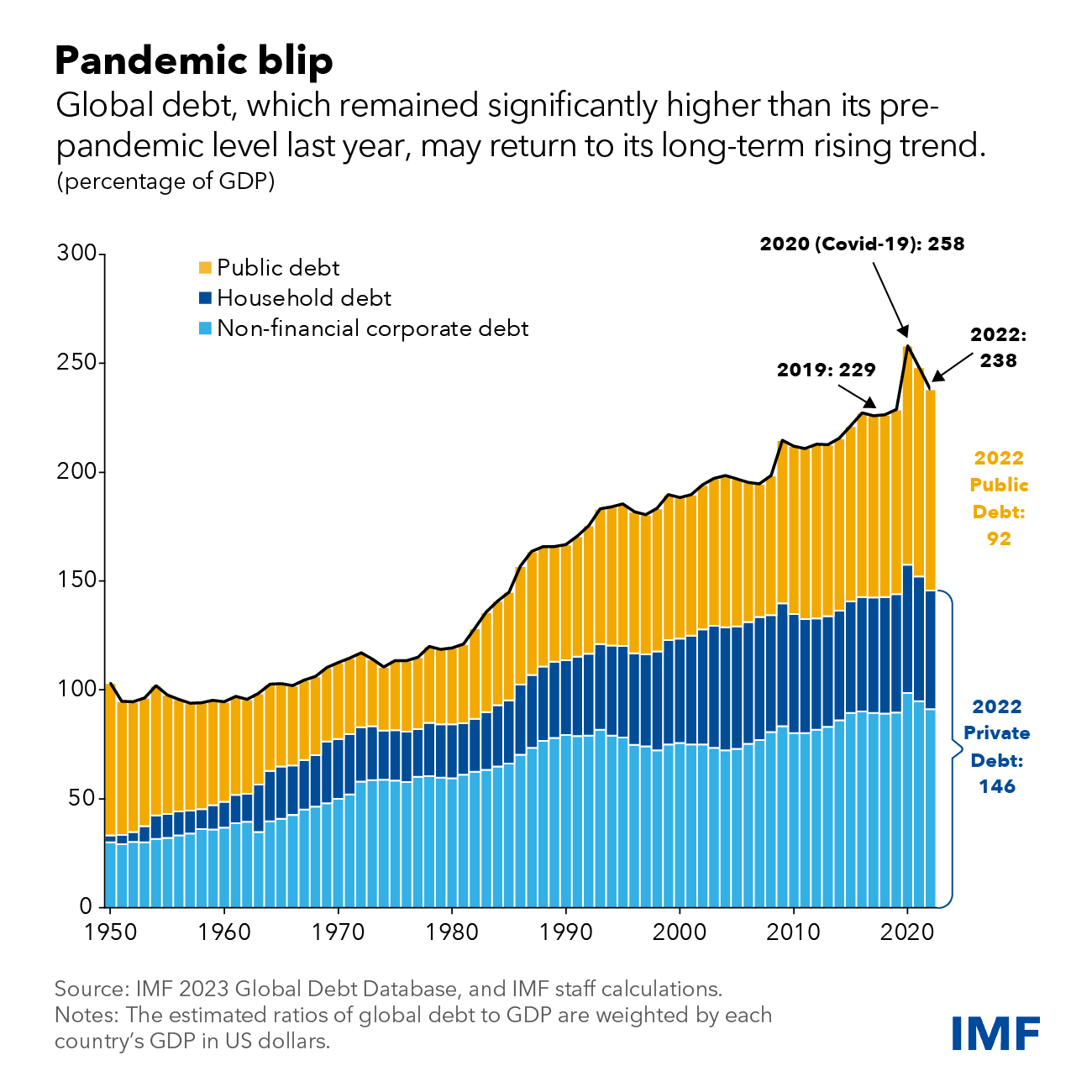

The global debt burden retreated for the second year in a row, even though it remains above its already-high pre-pandemic level, according to the latest update of our Global Debt Database. The total debt stood at 238% of global gross domestic product last year, 9 percentage points higher than in 2019. In US dollar terms, debt amounted to $235 trillion, or $200 billion above its level in 2021.

Policymakers will need to be unwavering over the next few years in their commitment to preserving debt sustainability.

Despite the economic growth rebound from 2020 and much higher-than-expected inflation, public debt remained stubbornly high. Fiscal deficits kept public debt levels elevated, as many governments spent more to boost growth and respond to food and energy price spikes even as they ended pandemic-related fiscal support.

As a result, public debt declined by just 8 percentage points of GDP over the last two years, offsetting only about half of the pandemic-related increase, as shown in our latest Global Debt Monitor. Private debt, which includes household and non-financial corporate debt, declined at a faster clip, dropping 12 percentage points of GDP. Even then, the decline was not enough to erase the pandemic surge.

Forces in debt trends

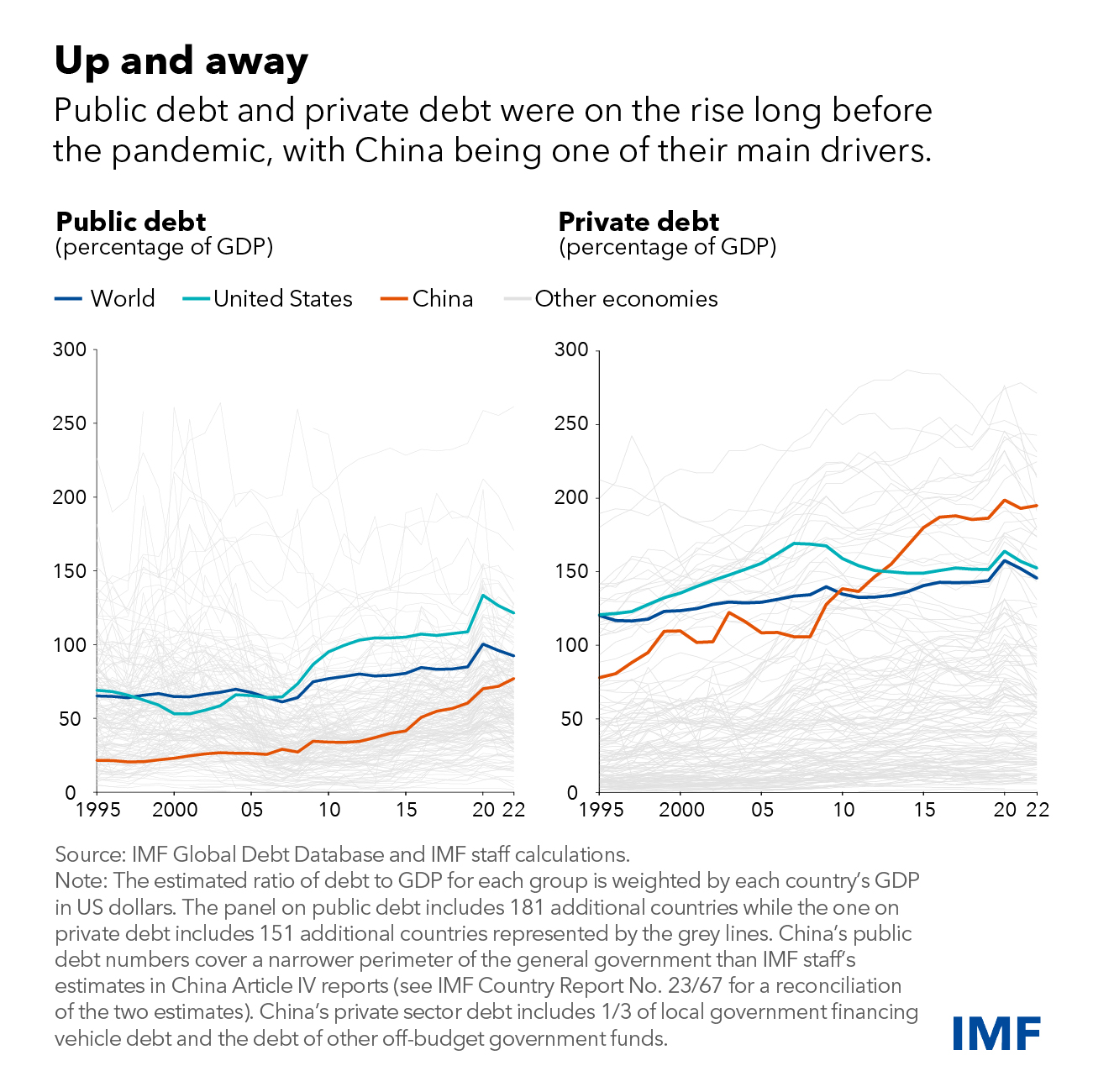

Before the pandemic, global debt-to-GDP ratios had risen for decades. Global public debt tripled since the mid-1970s to reach 92% of GDP (or just above $91 trillion) by end-2022. Private debt also tripled to 146% of GDP (or close to $144 trillion), but over a longer time span between 1960 and 2022.

China played a central role in increasing global debt in recent decades as borrowing outpaced economic growth. Debt as a share of GDP has risen to about the same level as in the United States, while in dollar terms China’s total debt ($47.5 trillion) is still markedly below that of the United States (close to $70 trillion). As for non-financial corporate debt, China’s 28% share is the largest in the world.

Debt in low-income developing countries also rose significantly in the last two decades, albeit from lower initial levels. Even as their debt levels, especially private debt, remain on average relatively low compared to advanced and emerging economies, the pace of their increases since the global financial crisis has created challenges and vulnerabilities. More than half of low-income developing countries are in or at high risk of debt distress, and about one fifth of emerging markets have sovereign bonds trading at distressed levels.

Tackling debt vulnerabilities

Governments should take urgent steps to help reduce debt vulnerabilities and reverse long-term debt trends. For private sector debt, those policies could include vigilant monitoring of household and non-financial corporate debt burdens and related financial stability risks. For public debt vulnerabilities, building a credible fiscal framework could guide the process to balance spending needs with debt sustainability.

For low-income developing countries, improving the capacity to collect additional tax revenues is key, as we discussed in our April Fiscal Monitor. For those with unsustainable debt, a comprehensive approach that encompasses fiscal discipline as well as debt restructuring under the Group of Twenty Common Framework—the multilateral mechanism for forgiving and restructuring sovereign debt—when applicable is also needed, as noted in the April World Economic Outlook.

Importantly, reducing debt burdens will create fiscal space and allow new investments, helping foster economic growth in coming years. Reforms to labour and product markets that boost potential output at the national level would support that goal. International cooperation on taxation, including carbon taxation, could further alleviate pressures on public financing.

Vitor Gaspar is director of the Fiscal Affairs Department of the International Monetary Fund, where Marcos Poplawski-Ribeiro is a deputy division chief and Jiae Yoo is an economist. This article was originally posted here.

4 Comments

So in the big picture and everything. NZ Inc is sweet as!

Let's crack open another $100b Bazooka!

How much of your retirement savings are tied up as someone else's debt that won't be repaid.

It's not the money you put in that counts, it's the value you get out.

There is no such thing as debt free money and all money is created as someones liability. Banks create new money when we borrow from them and governments also create new money when they spend and as their own liability. When we repay our loans to the banks this money is eliminated once more and government money is deleted again when we pay our taxes.

Man some of those grey lines are wild.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.