By Peter Drennan*

A few weeks ago, I found myself staring at yet another set of company records where IRD debt had metastasised from a manageable shortfall into something terminal. The pattern is depressingly familiar: a slow month, a decision to defer PAYE "just this once," and then, six months later, a balance that's doubled while the directors weren't watching. It got me thinking about a question that rarely gets asked directly: purely from a cost of capital perspective, how expensive is IRD debt actually?

I'm not talking about the legal exposure (that's significant), or the ethical dimensions (no comment), or the fact that PAYE is money you've already deducted from your employees' wages and are holding on trust. I wanted to isolate the finance question: if Inland Revenue has become New Zealand's largest involuntary lender to small business (and I'd argue it has) what interest rate are they charging?

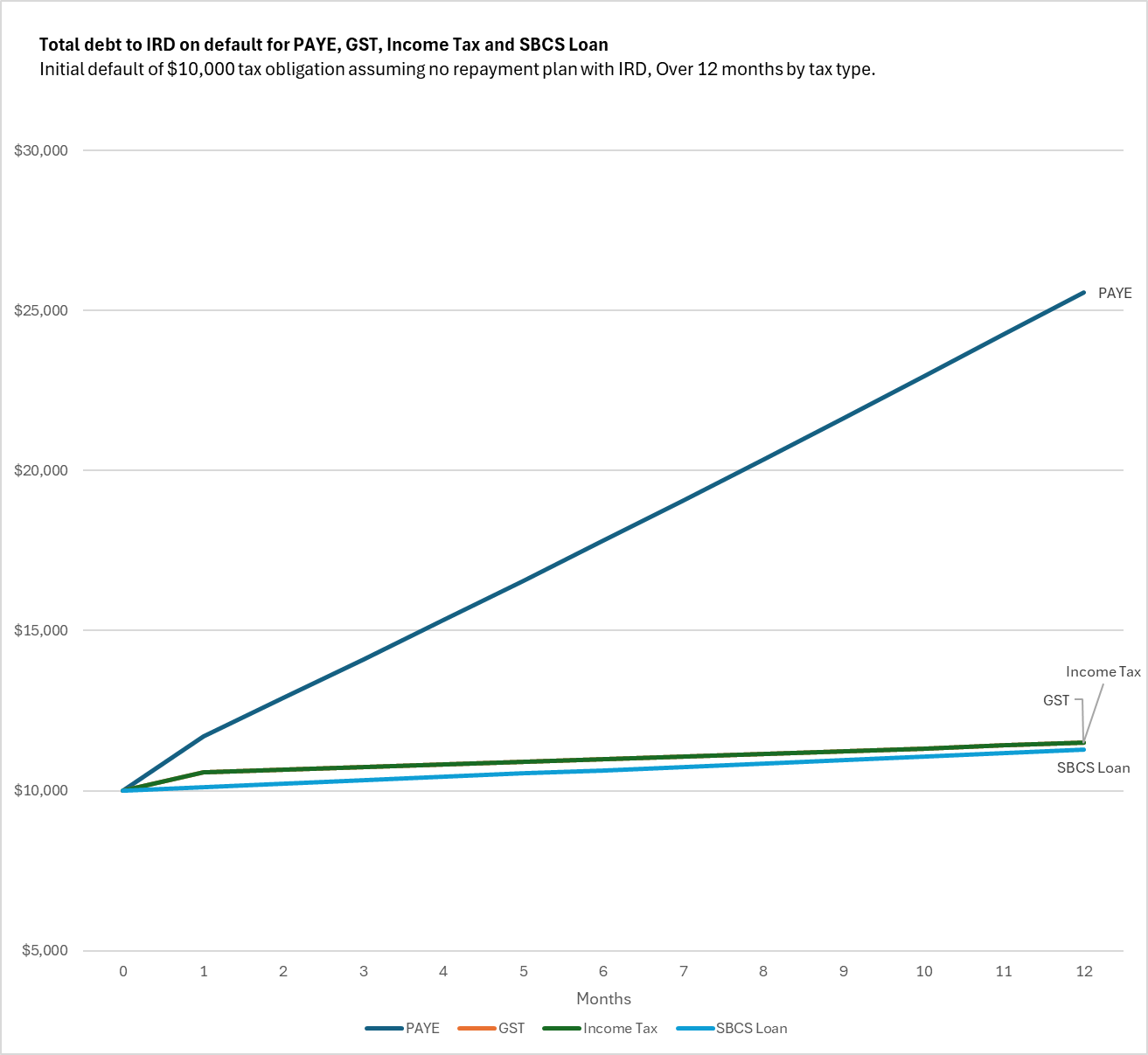

To find out, I modelled a $10,000 default across four categories of IRD obligation: GST, PAYE, Income Tax, and SBCS Loan (‘Small Business Cashflow Scheme’ colloquially known as ‘COVID loans’, now reaching their five-year maturity). The assumption was deliberately stark: no payment arrangement, no engagement with IRD, just straight default for twelve months. What does the final bill look like when you account for late payment penalties, non-payment penalties, and Use of Money Interest (UOMI).

What I expected to be a straightforward exercise (pull some penalty rates, build a spreadsheet, write it up) turned into hours of close reading through IRD guidance documents and the Tax Administration Act 1994. The penalty architecture is considerably more baroque than I'd appreciated. So after hours of research, I have nicely formatted chart confirming exactly what accountants and people in business already know: PAYE debt is bad.

The Divergence: What the Numbers Actually Show

What a boring chart, honestly I was hoping for more. GST and Income Tax are identical, and they are pretty similar to SBCS loan defaults. GST and Income tax, you pay about $1,500 in interest and penalties on your $10,000 default. The SBCS loan is a little lower at around $1,300. That's expensive relative to, say, a bank facility, but it's not catastrophic.

PAYE, meanwhile, has rocketed past $25,000. More than 150% growth in twelve months!

Why the divergence? The answer lies in section 139B(2B) of the Tax Administration Act. When the late payment penalty rules were reformed in 2017, Parliament explicitly removed the monthly 1% incremental penalty for GST and Income Tax, but retained it for PAYE and other employer deductions. They also levy a 10% monthly non-payment penalty. The policy rationale isn't hard to discern: PAYE represents funds held on trust for employees and the Crown. From IRD's perspective, non-payment isn't really "late payment"; it's closer to misappropriation.

Effective Interest Rates: Where It Gets Genuinely Interesting?

Here's where I went down a painful rabbit hole, that I'm not entirely convinced was productive, so perhaps a ‘ferret burrow’? I still have my doubts as to exactly how interesting this is for readers, but here we go.

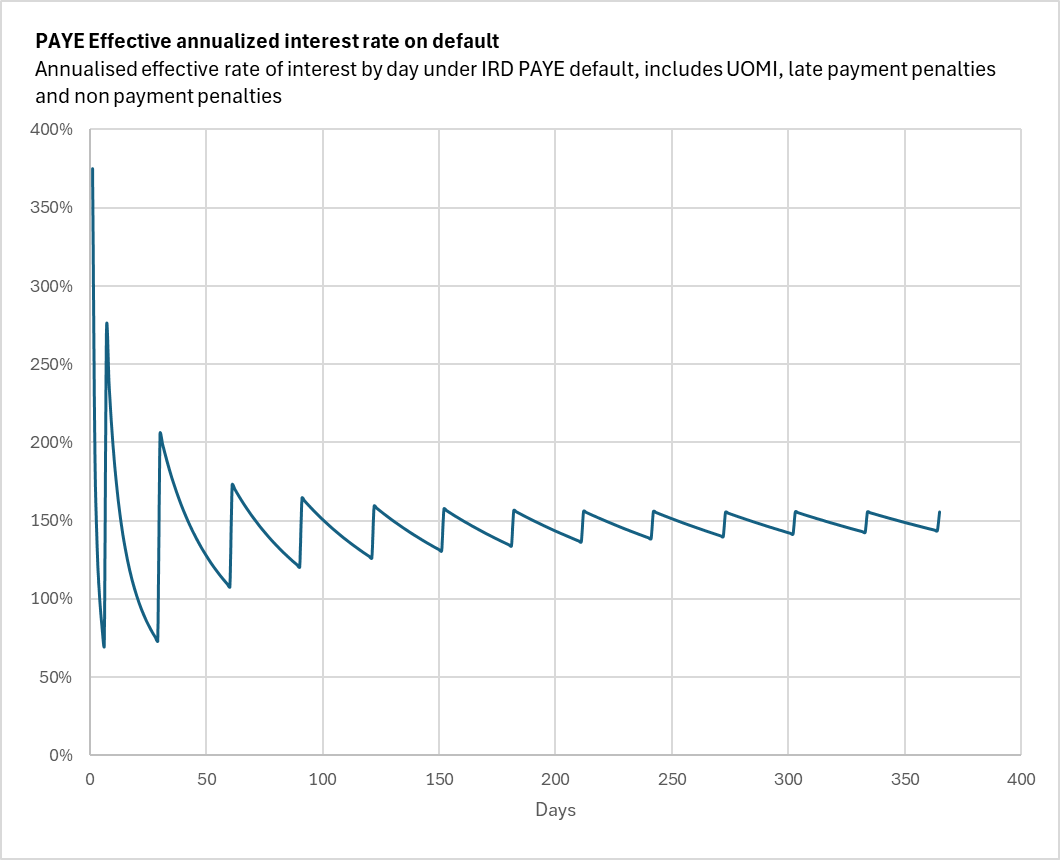

The penalty structure front-loads costs dramatically. You get hit with 1% on day one, then 4% on day seven, and (for PAYE) another 1% every month thereafter, and non-payment penalties of 10% per month. But what does that actually translate to in annualised terms? If you're comparing IRD debt to your overdraft facility or a finance company loan, you need an apples to apples comparison.

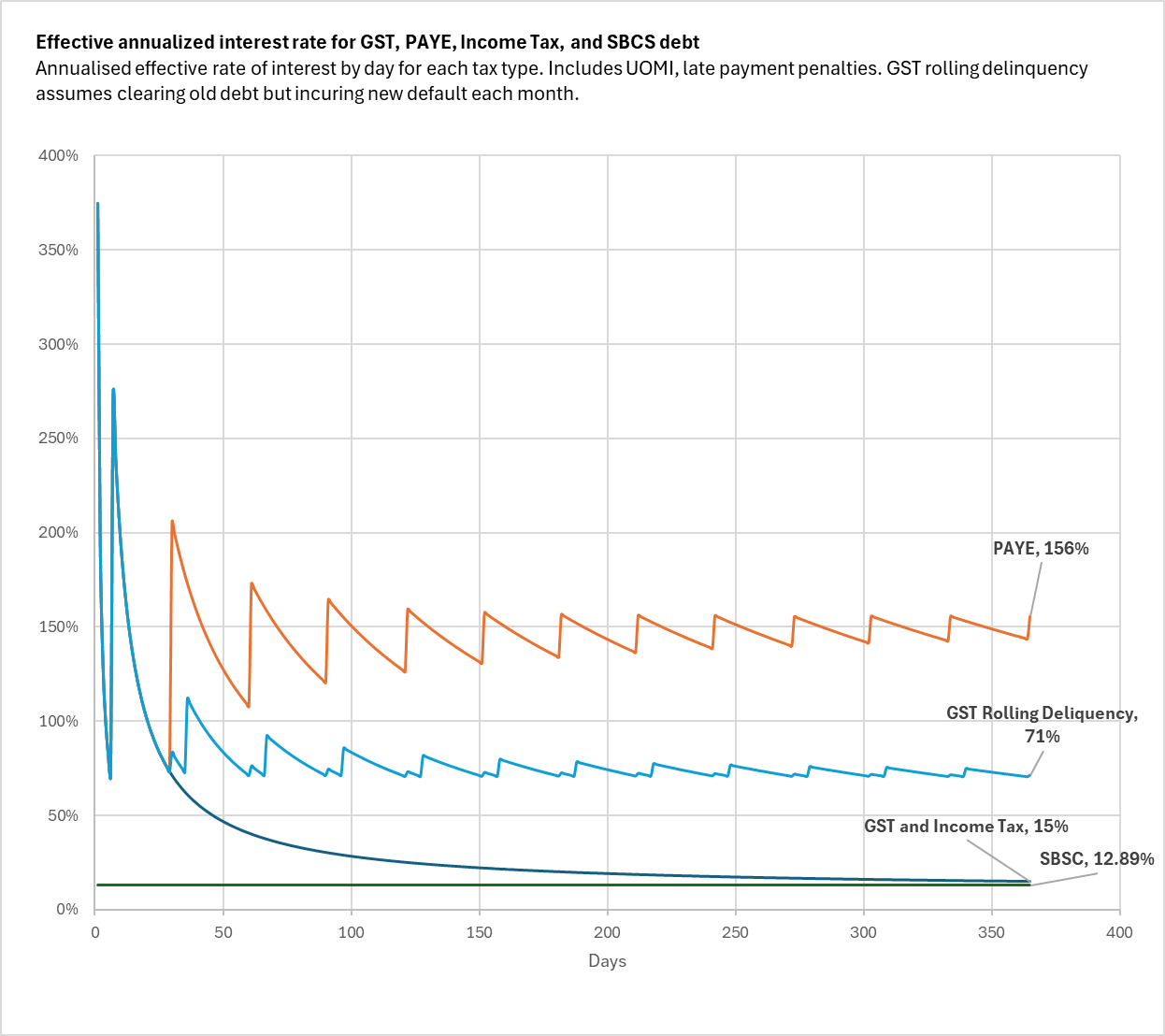

So in a valiant effort to generate a more interesting chart, I calculated the effective annualised interest rate by day for each debt type.

That initial spike above 350%? That's the day one 1% penalty expressed as an annual rate. (If you borrow $10,000 and pay $100 in "interest" after 24 hours, the annualised equivalent is astronomical, though admittedly somewhat artificial as a real-world comparison.) The rate drops sharply, spikes again around day seven when the 4% penalty lands, then sawtooths through the year as each monthly incremental penalty hits the growing balance.

By year-end, it's stabilised around 156% per annum.

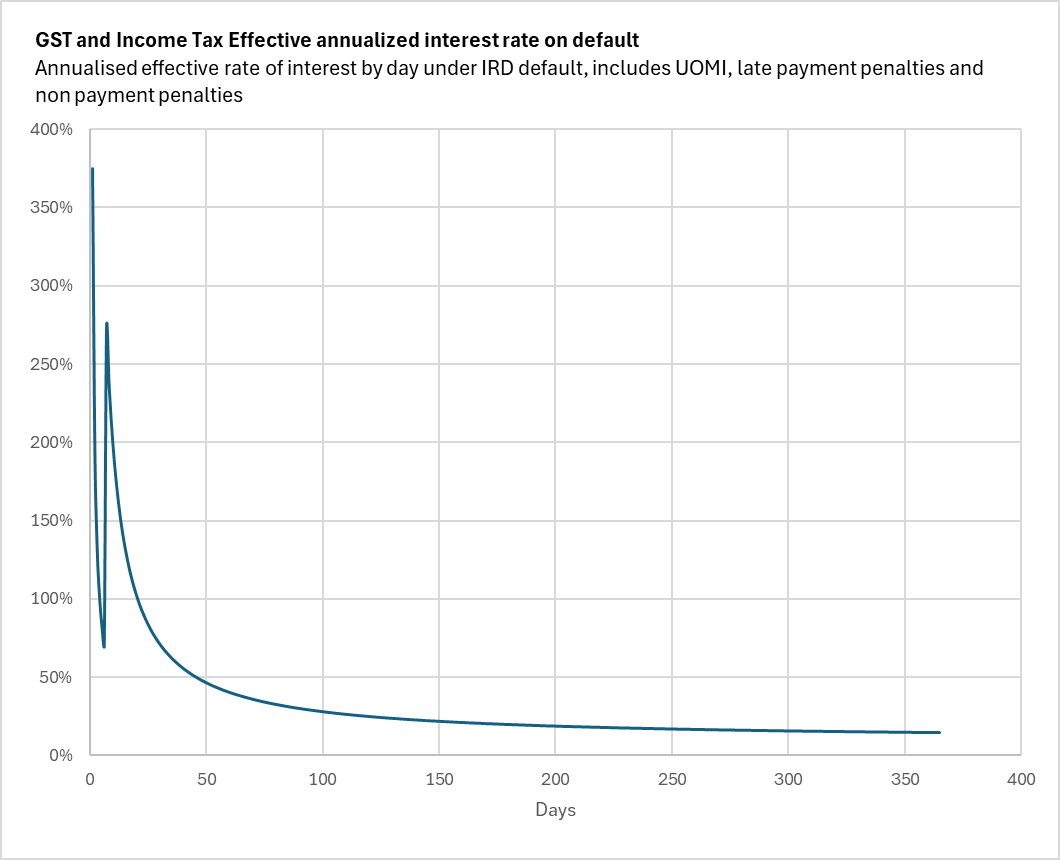

Now, what about GST and Income Tax you ask!?

Now that’s a nice chart. We see the same initial spikes appear, with days one and seven being just as punishing as PAYE in percentage terms. But because there are no further penalties after day seven, the curve simply decays toward the underlying UOMI rate of 9.89%.

“Why is this interesting?”

This was the question posed by my wife on Saturday when I forced this revelation into her consciousness.

Well, once you've absorbed the initial penalty hit, the marginal cost of carrying GST or Income Tax debt is relatively modest. If your business can access capital at less than 10%, then yes, pay IRD and be done with it. But if you're already running an overdraft at 12 to 15%? The pure finance calculation suggests leaving the GST debt in place might actually be cheaper than drawing further on the facility. (I want to be clear: this is not advice. Go back to the throat-clearing at the start of the article regarding morality and legal consequences. But as a finance exercise, the numbers are what they are.)

As for the SBCS loan chart, I won't bother including it, it’s a very boring chart. It's a flat line at 12.89% (UOMI plus the 3% standard loan rate). No penalties, no spikes, no sawtooth. Just 20 minutes of chart formatting I will never get back.

The Hidden Trap: Rolling GST Delinquency

Here's where maybe we are edging towards something interesting to us uninteresting people.

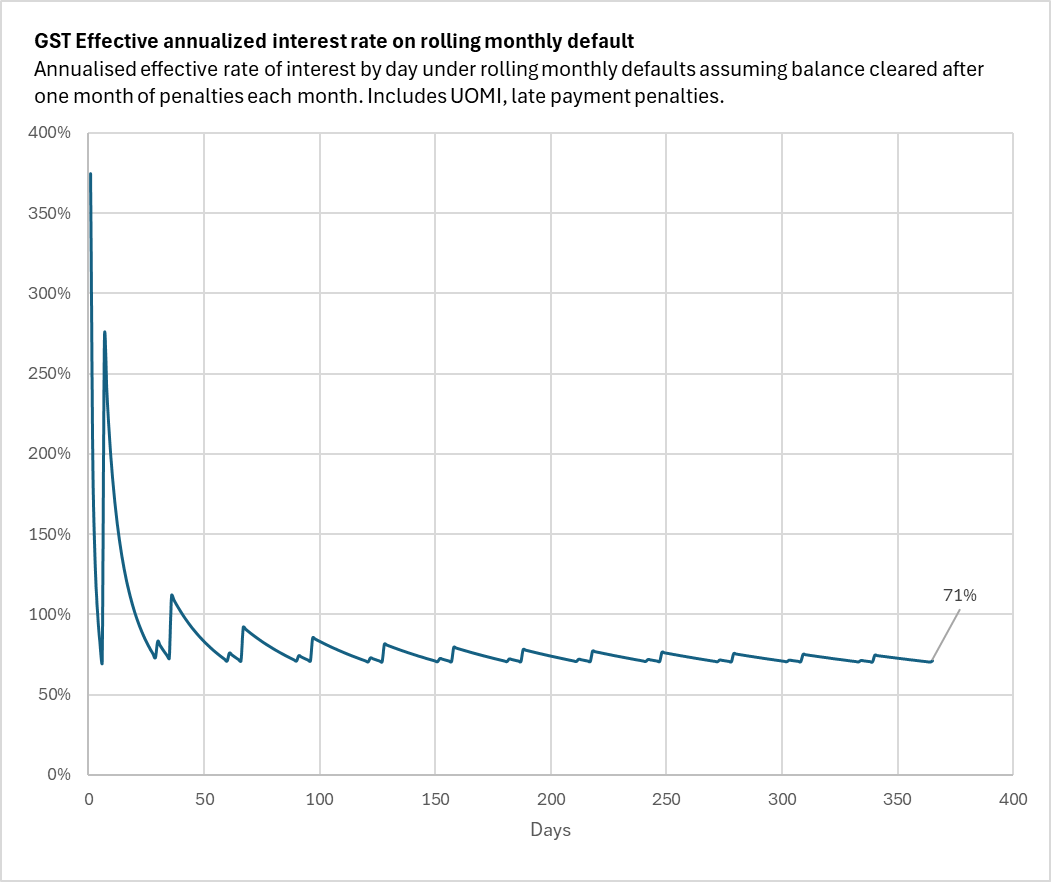

Knowing that GST penalties are front end loaded, I modelled a different scenario: the perpetually one month behind business. This is the company that always pays its GST, eventually. They clear last month's debt each cycle, but they're always running 30 days late on paying the last return. They're not accumulating arrears; they're just chronically behind.

Is this a realistic scenario? In its pure form, probably not, since a taxpayer this consistent would likely qualify for (and benefit from) a payment arrangement with IRD, and many businesses don’t return monthly. But in my experience, plenty of businesses run some version of rolling delinquency: cash flow timing issues, administrative slippage, the perennial optimism that next month will be different. The pattern is more common than you'd think (albeit less extreme).

Rolling delinquency is costly.

See that sawtooth pattern? Each spike is a new GST return triggering fresh day one and day seven penalties. Because the business keeps hitting those front loaded penalties on new debt every month, the effective rate never gets a chance to decay toward UOMI. Instead, it settles out at around 71% per annum.

Let me say that again for the 7 readers that made it this far: 71% effective interest for the privilege of being perpetually one month behind!

That's over $7,000 in penalties on what is effectively a $10,000 timing difference. The business isn't going deeper into debt (they're just always running late) and yet the annualised cost is nearly half as expensive as a full PAYE default.

The combined picture looks like this:

PAYE at 156%. Rolling GST delinquency at 71%. Single GST or Income Tax defaults trending toward 15%. SBCS loans flat at 12.89%.

What This Means in Practice

So what should a business owner actually do with this information? Other than always pay your taxes. (I’m nervous that the 7 readers that make it this far all work at the IRD.)

The priority order is clear. PAYE comes first, always. At 156% effective interest with monthly compounding, it's not financing; it's a financial emergency. And that's before you factor in potential criminal liability under section 143 for directors who knowingly apply PAYE funds to other creditors.

Second priority: don't let GST become a rolling problem. A single late GST return is painful upfront but manageable over time, as the effective rate decays toward UOMI as the months pass. What you want to avoid at all costs is the perpetual one month behind pattern. At 71% effective interest, rolling GST delinquency is the hidden trap in this analysis: it doesn't feel like a crisis, but the cumulative cost is extraordinary.

Among the remaining options, the differentiation is less dramatic. Single GST and Income Tax defaults are treated identically under the penalty rules (both tracking toward approximately 15% by year-end). SBCS loans in default are marginally cheaper at 12.89%, with no penalty volatility.

One pattern worth emphasising: the front loaded penalty structure punishes frequency more than duration. A business that's consistently seven days late across six bi monthly GST periods is paying those initial 1% and 4% penalties six times over. Even without monthly compounding, that adds up to an effective rate far worse than a single default left to mature.

The actionable takeaway? From a financing cost perspective, if you're in a rolling delinquency pattern with IRD for a debt other than PAYE, the single most valuable thing you can do is break the cycle. Get current on one return, even if it means carrying a larger balance on older debt. Contact IRD about a payment arrangement (section 139BA provides meaningful penalty relief for taxpayers who engage proactively). The month to month pattern feels manageable, but the cumulative cost is anything but.

Some final caveats

I'm reliably informed that SBCS default interest is non deductible, which would affect the after tax comparison. I confess I've reached the outer limits of my tolerance for this corner of tax administration; talk to your accountant on the deductibility question.

And very importantly, before business owners run straight into the arms of our nation’s high interest lenders: IRD debt in most cases don’t have recourse to your personal property, while most lenders will want your house as security, it’s not all about the interest rate.

Peter Drennan is a practising lawyer and leads Waterstone’s Christchurch office. Waterstone specialises in recovery and insolvency work and provides consulting and advisory support to companies in financial distress or considering turnaround strategies.

6 Comments

When I could see that my business was getting itself into trouble, I immediately ceased trading. There are two main causes (in my experience) of ballooning tax debt:

1. Companies continue to trade (often recklessly or are already insolvent in legal terms) when it's they obvious they are past the point of no return.

2. The IRD allows these companies to continue trading when they should be applying to the courts to have them wound up much sooner.

Most small businesses are not viable. They wouldn't attract any capital investment and are generally a lifestyle option for their owners. That means there's always a fine line between treading water and insolvency.

Agreed. Perhaps a six monthly record of solvency could be worthwhile. It would allow people to be fully informed wether they do business...or not.

Kitchen Things comes to mind....

An interesting analysis for me would be the level of tax debt recovery from delinquent businesses.

My perception is that at a basic level, those unpaid Ird liabilities enable spending in other areas. Equating to compliant taxpayers funding perhaps an artificial competitive position for their goods/services in the marketplace; or maintaining lifestyle.

Either way, if there is $100k owed to IRD (without added penalties) then meeting that shortfall in funding to the crown falls on all other taxpayers. If, in the end 50% of that debt is recovered (through liquidation/bankruptcy) it still leaves a considerable burden on compliant taxpayers.

So, what is the actual recovery of delinquent tax?

Another perception is that this is white collar crime attracting wet bus ticket punishment. I reckon the penalties should be more severe for tax delinquency (fraud) than other non-IRD related fraud. Because tax fraud is against all New Zealand taxpayers.

I believe fraud is when you under state profits to IRD on accounts, rather then failing to pay the required amount due to lack of funds (technically insolvency), I guess continuing to trade insolvent is also applicable here as a crime.

How many tax liquidation are out there...?

I believe it offensive to not pay tax on time on the basis it's the cheaper option to not pay.

It's a social obligation, not a purchase decision.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.