Last week, the Biden Administration issued a formal advisory warning to US firms operating in Hong Kong. It said developments like the new National Security Law in Hong Kong meant that ‘the risks faced in mainland China are now increasingly present in Hong Kong’. The ‘one country, two systems’ approach, the formulation agreed for the handover in 1997, is de facto over.

Developments in Hong Kong often illustrate the state of the US/China economic and political relationship, as I have noted before. And recent developments suggest three broader insights on the state of the geopolitical environment.Last week, the Biden Administration issued a formal advisory warning to US firms operating in Hong Kong. It said developments like the new National Security Law in Hong Kong meant that ‘the risks faced in mainland China are now increasingly present in Hong Kong’. The ‘one country, two systems’ approach, the formulation agreed for the handover in 1997, is de facto over.

Bearing the cost

First, neither the US or China show any sign of reducing tensions – with both being prepared to absorb the associated costs. The ongoing extension of mainland Chinese political and legal practices into Hong Kong is leading to an exit of meaningful numbers of Hong Kongers and foreigners, risking its status as a global hub.

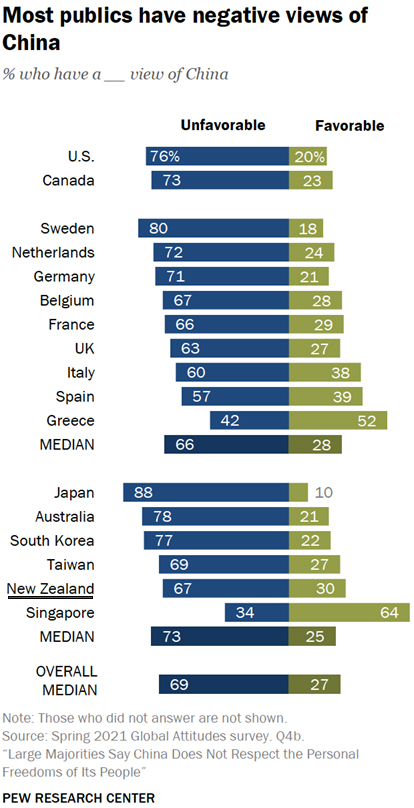

Elsewhere, Chinese regulators unexpectedly restricted ride-sharing company Didi, sending its just-listed US shares down by ~25%. This will likely chill future Chinese listings in the US. And although President Xi recently claimed that he wanted a reset in China’s relations with the rest of the world, bilateral economic sanctions (e.g. Taiwan, Australia) and wolf warrior diplomacy continue. This contributes to ongoing weakening in China’s international reputation, according to the latest Pew survey.

A number of Western countries are also prepared to absorb the costs of more fractious relationships with China. The comprehensive investment agreement (CAI) between the EU and China was halted after sweeping Chinese sanctions against European politicians and institutions. The UK recently announced that it was reviewing the Chinese purchase of semiconductor firms. And Secretary Yellen dismissed the possibility of restarting the US/China Strategic Economic Dialogue.

These events suggest that a range of countries are willing to bear economic costs associated with this geopolitical rivalry. Under President Xi, China will likely continue with this approach for some time.

Indeed, China will argue that the costs are manageable – IPO activity in Hong Kong remains strong, for example, as are Western financial flows into Chinese markets. And bilateral US/China trade flows are growing healthily.

And the consensus policy view (particularly in the US, but more broadly) on China has changed from a focus on engagement to an explicit recognition of strategic rivalry. It is one of the few issues on which there is a measure of bipartisan agreement in Washington.

Economic rivalry: from defense to offense

Although there are obvious hard power dimensions to the rivalry between China and the US (and others), with military spending increasing, this is importantly a conflict that is playing out in economic, financial, and technological domains. It is war by other means. Both are aiming to build positions of strength in the commanding heights of the C21 global economy.

There has been a marked rotation of emphasis over the past year, particularly in the US, from defensive measures to more positive, forward-learning measures. The first stage of the economic rivalry, notably under the Trump Administration, was about imposing tariffs on Chinese exports, various economic sanctions, and restrictions on investments into sensitive sectors.

Although the process of implementing competing tariffs has now largely ended, there are many residual barriers and new restrictions are being imposed. But the policy focus is moving to more positive measures. Massive amounts have been legislated (and more proposed) in the US for investment in infrastructure and innovation in the US. Priority areas include AI, big data, 5G, semiconductors, and so on.

These investments are often explicitly framed around rivalry with China. In an April speech to Congress, President Biden said that ‘We’re in competition with China and other countries to win the 21st century… We’re at a great inflection point in history.’

These are the sort of measures that China has been making for some time: Made in China, the Greater Bay Area initiatives (including Hong Kong), and so on. And Europe is focusing on strategic autonomy, which has implications for strategic investment in innovation: from semiconductors to developing leading global competitive positions in the green economy.

This innovation-heavy policy approach is familiar to smaller economies. But this big power rivalry is likely to lead to competing technology and regulatory blocs, which will require other small countries to make hard choices – from 5G networks to M&A activity. And increasingly, the US is forcing some of these choices.

There are risks of getting caught in the crossfire. This will be a more challenging phase to navigate than the trade wars, which small open economies were able to navigate reasonably well; it was the direct protagonists that incurred the highest costs.

The silver lining to geopolitical rivalry

There are costs to global economic fragmentation, the disruption of supply chains, and so on. But as in other domains, competition between countries can be a good thing – creating sharper incentives for investment and innovation.

During the Cold War of course, geopolitical competition led to greater innovation (as well as the substantial costs). The most obvious example was President Kennedy’s commitment to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade, largely motivated by the rivalry with the Soviet Union.

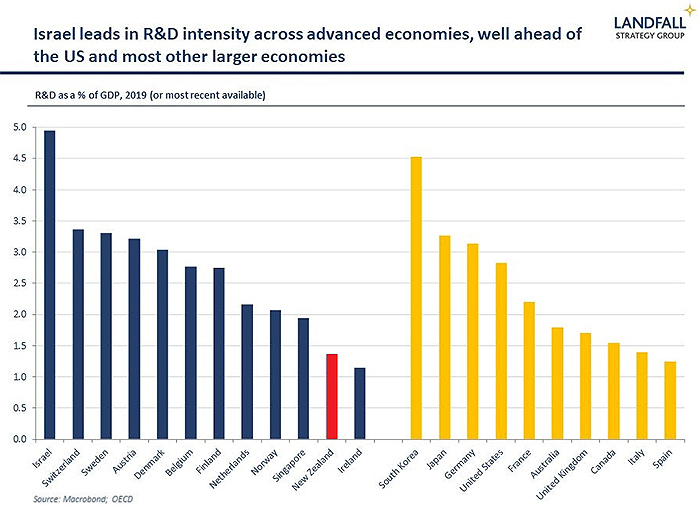

Israel is another example in which regional tensions have supported strong innovation performance, with spillovers from the defense innovation complex. Israel’s R&D spending is among the highest across advanced economies.

The shift to a more positive agenda that leads to more investment in human capital, innovation, and infrastructure can create economic upside at a national level, as well as for firms that are active in relevant sectors (although there are risks associated with aggressive industrial policy, creating national champions, and so on).

It would be nice to return to a focus on deep engagement between the major power blocs, but the reality is that geopolitical tensions will be a defining characteristic of the decades ahead. The silver lining may be more rapid innovation than would otherwise be the case.

David Skilling is the Founding Director of Landfall Strategy Group.

4 Comments

the political system and the quality of the political leadership in nearly all western countries will almost guaranty its countries irreversible decline in coming decades.

You are probably right about most of the politicians in western countries. Nobody with talent would want the relentless scrutiny they get from our voracious media. However the political system in western countries does permit change of leader and under stress sometimes the great leader appears.

Compare that to Emperor for life President Xi. It is possible that he is the most able person in the world but what is the process for replacing him when he becomes less mentally able or dies? And what if he is not really that able and achieved his position via family contacts, ruthless behaviour and luck. It is possible for even China to decline given a bad autocratic ruler - there is plenty of historic proof of that.

If you are familiar with some of the worst dictators of the 20th century, such as Stalin, Hitler, Gaddafi, Mao and Franco, you know Xi is no different. He is taking the People's Republic down that road. During the process, the United Front is getting more cues from Volksdeutsche.

"the reality is that geopolitical tensions will be a defining characteristic of the decades ahead."

Masterful understatement.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.