By Bernard Hickey

Any New Zealander who lost money in our finance company collapses of 2006-08 will know how many individual investors in China's shadow banks will be feeling right now.

It's a sense of foreboding and in many cases disbelief.

Some will be hoping it all works out and that the Government will bail them out. That worked in New Zealand for South Canterbury Finance, but not for most. Others will be blissfully unaware, as most New Zealanders were through 2006 and 2007 as the carnage unfolded quietly inside the balance sheets of these finance companies and as banks quietly withdrew their support. Some Chinese investors have already started complaining to the banks that distributed them, and in one case, to the Police.

The parallels between New Zealand's shadow banks and China's shadow banks are close, albeit on massively different scales.

New Zealand's finance companies were largely unregulated and their lending was mostly to closely connected property developers. They gathered deposits from savers by offering interest rates of 10% or more. They existed because savers believed they would never fail and they filled a gap left by banks who thought such lending was too risky.

China's shadow banks are very similar. They have been largely unregulated, although that is beginning to change. They also have boomed because they offered savers much higher rates than the repressively low rates offered by China's state-owned banks. These shadow banks, which are called trusts or Wealth Management Products (WMPs), are also exposed to just a few or single loans and they use their names to present an image of strength and dependability. Remember 'Provincial Finance' and Hanover Finance's 'Weathering the Storm.'?

One big difference is the connection between these trusts and government-guaranteed banks. In China these trusts are often sponsored and marketed to clients through banks, although they are carefully kept off balance sheet and are in theory not guaranteed.

The best example is the shadow bank in the news this week because it's due to default on Friday January 31. The "Credit equals Gold Number One" (yes that is the actual name translated into English) trust account was marketed by state-owned ICBC to its high net worth customers and raised US$500 million. The trust then lent all that money to a coal miner that went bust in 2012 and ICBC has been vague on whether it will pay it out, saying it is not responsible for paying it out when the account matures on Friday.

Here's a backgrounder from Bloomberg and one from Reuters, which suggests ICBC will blink and pay out. As recently as this week the chairman of ICBC told reporters in Davos that the potential collapse of the shadow banks was a "very good opportunity to educate the investors" about how it was not government guaranteed.

China's shadow banks and WMPs now owe depositers more than US$5 trillion or more than 50% of Chinese GDP. They are now responsible for more than 30% of all Chinese lending and more than US$660 billion of the deposits in these shadow banks are due to mature this year.

This is where the big difference between China's shadow banks and New Zealand's finance companies lies. At their peak New Zealand's finance companies had collected around NZ$10.5 billion of deposits or about 7% of GDP and 4% of all lending. China's shadow banks are, therefore, a much bigger deal relative to China's economy than our finance companies were to ours.

The fear, as outlined here by George Soros in a Project Syndicate commentary, is that any crisis in the shadow banking sector will spill over into the Chinese economy, which has been powered since 2008 by massive credit growth.

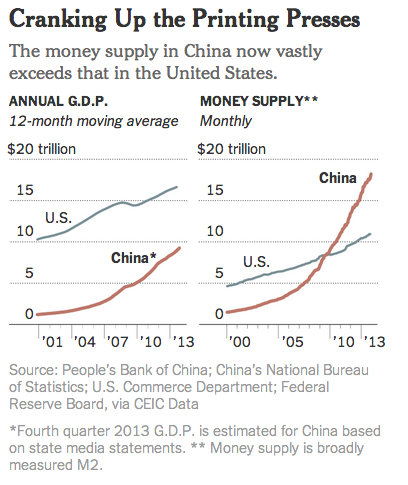

This New York Times backgrounder and chart explains just how stunning the credit growth has been.

It shows that China's money supply has tripled since 2006. Shadow bank lending has more than tripled in the last three years.

This explosion of bank and non-bank lending helped China avoid the worst of the Global Financial Crisis. Lending inside China almost doubled to 220% of GDP between 2008 and the end of 2012. No developed or developing nation has grown credit that quickly in that short a time without some sort of bust soon after.

Reserve Bank Governor Graeme Wheeler told Parliament's Finance and Expenditure select committee in November that China's shadow banking system was probably the greatest risk for New Zealand's economy, given that China was now New Zealand's largest trading partner.

Here's what he said back then:

One of the things that I was reading recently was a report by Fitch, which is one of the rating agencies, which in essence said that if you look at the housing exposure, or the lending exposure if you like, in the US banking system, it totals roughly around US$15 trillion and it has taken the American banking system 235 years to get there. The Chinese banking system, which includes the formal banking system and the shadow banking system, has got to a delta of US$14 trillion in 5 years.

But so what?

One argument put forward by those less worried about the growth of China's lending and its shadow banking system is that, ultimately, China can fix its own problems because the various players involved are ultimately controlled by the central government. China's savers may not be the same as the Government, but they don't have much individual power, or even the vote.

Also, very little of China's debt is to foreign parties and its own 'national account' is very healthy with foreign reserves of almost US$4 trillion. China does not face the same debt-driven financial crisis faced by the likes of Thailand or South Korea or Russia in the late 1990s, who were all hammered when foreign creditors asked for their money back at the same time.

Many of China's shadow bank's loans were marketed by state-owned banks to state-owned companies, both at a local and national level.

The theory, say some, is that the Government could simply solve the problem by organising a large debt restructure where the slates are wiped clean and netted off against each other without the economy skipping a beat. China did a similar massive state bank debt restructure and recapitalisation in the early 2000s that didn't slow growth that much.

We've already seen ICBC appear to cave in to pressure to 'bail out' the off-balance sheet vehicle to keep the depositors whole. As we seen throughout the western world, central banks and Governments have an unlimited ability to use taxpayer resources and money printed out of thin spreadsheets to ensure banks stay solvent and party keeps rockin'.

In China, inflation is also not a problem, so the option of encouraging yet more lending by banks is not off the table. Even in the last year, China's authorities have blinked several times when credit stresses have forced interbank interest rates up and economic growth has slowed. Stability is valued above most other reform goals in China.

Are we immune?

Another argument is that even if a credit crunch causes an economic slowdown in China, it may not affect New Zealand that much. The explosion of credit in China in the last five years largely went into investment in infrastructure such as apartment buildings, roads, railways, power stations and airports.

That credit bought an awful lot of concrete and steel, which was produced with iron ore and coal mined in Australia.

However, Chinese consumers did not borrow money to buy the dairy products and meat that New Zealand has exported to China. They're also not borrowing to come on holiday here. China's consumers are still heavy savers.

Indeed, the Chinese Government under new leader Xi Jingping has said he is determined to rebalance the Chinese economy away from investment and more towards consumption. That would tend to favour New Zealand, which exports products and services for consumers, over Australia, which exports the raw materials used in investment. This internal shift in China is one of the reasons why the New Zealand dollar has appreciated so much against the Australian dollar over the last year.

We'll see. Doomsayers about China's ability to keep growing fast have been proven wrong time and again by China's leaders, who have pulled plenty of levers to keep the engine running. Although the biggest lever has been the credit lever and just about everyone, including China's leaders, say that lever(age) has to be relied on less and less.

A slump in lending by China's shadow banks may not end New Zealand's export boom to China.

But it is certainly worth keeping an eye on.

19 Comments

It would certainly be interesting to investigate the quality of the assets backing shadow lending. How much has quality cashflow,how much of the debt is being rolled over with more debt and how much interest is being serviced with new debt.

Thanks Hugh, China can probably contain its problems internaly, lets hope.

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/CHIN-02-240114.html

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Global_Economy/GECON-01-270114.html

This site is starting to bore me, its doesn't reload properly and I don't get the latest comments. So Im thinking of weaning myself off.

Andrewj,how will China deal with the situation without doctoring up some other scheme that simply shifts the problem? The only way,in my view, is massive asset devaluation and deleveraging.

They may decide to just, 'save themselves' and bugger the rest of us. They do have rather large reserves.

Asians in general are good at feeding themselves and Im just not sure just how much they need our milk imports, there are two obvious alternatives to baby formula.

Hugh, they are a command economy, even if at times it looks like a plutocracy,they have much more control than we do. They may just pull a few levers.

Have you read,' China in ten words'?

http://www.amazon.com/China-Ten-Words-Yu-Hua/dp/0307739791/ref=sr_1_1?s…

Its a pleasure to be of help Hugh. Im just about to sit down and read this

http://www.amazon.com/Tide-Sunrise-History-Ruso-Japanese-1904-1905/dp/B…

Interesting stuff Andrew. Is there a parallel with Japan in the 1930s? I hope not. It seems the Japanese central bank created lots of money and so allowed Japan to escape the depression early. However, when the time came to restrain the spending the Japanese finance minister was shot in his bed in a military coup.

Takahashi “brilliantly rescued Japan from the Great Depression through reflationary policies,” Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke said in a speech in 2003. His policy package increased the fiscal deficit, depreciated the currency and expanded the money stock, with robust growth and mild inflation for the five years from 1933, according to a research paper co-authored by Masato Shizume, an economist working for the BOJ.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-03/japan-finance-minister-models-…

Bill English better watch his step.

I think the USA will honor its treatry with Japan and stand by them, those Nuc subs of the coast will keep China in a, talk only mode.

I see they are building two new aircraft carriers

http://swampland.time.com/2014/01/20/china-doubling-its-aircraft-carrie…

Yes, the US military see Japan and Taiwan as large aircraft carriers moored strategically off China.

I find it interesting that Ben Bernanke at al (including Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, surprisingly) think Korekiyo Takahashi was brilliant but fail to see the connection with the enabling of miltarism in their society. That's what government finance is all about, enabling the military. Much of the current financial mechanism was developed in Britain in order to fund the Napoleonic wars.

To me the US credit crisis was caused by the monetary response to the costs of US warfare. Greenspan kept the Fed interest rate low so Bush could afford to invade Iraq and Afghanistan. The housing bubble and the increased militarisation of US society (including the internal security regime, spying etc) was the result. It is easy for a central bank to bail out the government but the sections of society that benefit do not give up their privileges without a fight.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takahashi_Korekiyo

Takahashi continued to serve as Finance Minister under the administrations of Tanaka Giichi (1927–1929), Inukai Tsuyoshi (1931–1932), Saitō Makoto (1932–1934) and Okada Keisuke (1934–1936). To bring Japan out of the Great Depression of 1929, he instituted dramatically expansionary monetary and fiscal policy, abandoning the gold standard in December 1931, and running deficits.[3] Despite considerable success, his fiscal policies involving reduction of military expenditures created many enemies within the military, and he was among those assassinated by rebelling military officers in the February 26 Incident of 1936

Strangely enough,I've just been reading about the massive fiscal deficit Reagan and co were running during the Arms Race of the 1980s. This of course was a major contributor to our high interest rates at the time.

The scary thing is that David Stockman reckons the US now spends $650 billion on security, compared to $350 billion at the height of the cold war, both figures in todays dollars. As he puts it, the US presently has no industrial strength enemies. David Stockman was Reagan's budget adviser (until they fell out) so has credibility in that he understands how the US budget works (which is a vanishingly rare ability).

There are always threats and potential threats from a military perspective but the budget process is meant to restrain the funding of military endeavours where appropriate. The whole development of the parliamentary process is based on enabling military funding in times of war and on restraining it in times of peace.

When the central banks funds the government in times of economic difficulty it takes the pressure off the government to make the difficult budget reforms that led to the economic problem. Usually the military has been the main beneficiary of enlarged government spending up to this point.

Yes, well Britain clearly suffers from a form of Dutch Disease from the oustanding success of the world financial services (and money laundering?) centre located in the City of London. Perhaps they should move the government from the City of Westminster next door and locate it somewhere more central and representative like Birmingham.

Imagine what New Zealand would be like if it was run from Auckland.

Forget China - too big to fail and not really worth stressing over.

FYI here's the Head of Morgan Stanley's Emerging Markets and Global Macro research division with an Op-Ed in the FT titled "China's debt-fueled boom is in danger of turning to bust."

He points out no other emerging market has grown debt as quickly as China did and avoided a bust, or at least a very substantial slowdown, even those countries with big foreign reserves.

"Those who trust in China’s exceptionalism say it has special defences. It has a war chest of foreign exchange reserves and a current account surplus, reducing its dependence on foreign capital flows. Its banks are supported by large domestic savings, and enjoy low loan-to-deposit ratios. History, however, shows that although these factors can help ward off some kinds of trouble – a currency or balance-of-payments crisis – they offer no guarantee against a domestic credit crisis.

"These defences have failed before. Taiwan suffered a banking crisis in 1995, despite having foreign exchange reserves that totalled 45 per cent of GDP, a slightly higher level than China has today. Taiwan’s banks also enjoyed low loan-to-deposit ratios, but that did not avert a credit crunch. Banking crises also hit Japan in the 1970s and Malaysia in the 1990s, even though these countries had savings rates of about 40 per cent of GDP. Furthermore, there is no strong link between the state of the current account and the outbreak of credit crises."

It's a must read, I reckon.http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/cfcb0568-8749-11e3-9c5c-00144feab7de.htm…

Bernard , is it time to re-visit your call for a 30 % collapse in house prices ?

.... particularly in Auckland , houses are at such a stretched multiple to household incomes , plus FHB's and investors have so heavily loaded up on debt .... and the Reverse Bank is champing at the bit to raise the OCR .....

Is the time-bomb ticking at long last ?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.