Here's my Top 10 items from around the Internet over the last week or so. As always, we welcome your additions in the comments below or via email to bernard.hickey@interest.co.nz.

See all previous Top 10s here.

My must reads are #1 and #2 on how new technology changes a lot of things.

1. Good thing or bad thing? - I'm fascinated with the amazing pace of technological change and how it's transforming the way we work, how our economy works and the way humans interact.

It's not all good. Or all bad.

But it is a thing.

So this Nautilus piece on how we'll be able to record, database and search everything we and everyone else has ever said is thought provoking.

It means we could check exactly what we said to that supplier in a phone call last year. Or whether the minister really did say before the last election the exact opposite of what he or she is promising now.

It's both scary and exciting. And it would change the way we think about what we're about to say.

Much of what is said aloud would be published and made part of the Web. An unfathomable mass of expertise, opinion, wit, and culture—now lost—would be as accessible as any article or comment thread is today. You could, at any time, listen in on airline pilots, on barbershops, on grad-school bull sessions. You could search every mention of your company’s name. You could read stories told by father to son, or explanations from colleague to colleague. People would become Internet-famous for being good conversationalists. The Record would be mined by advertisers, lawyers, academics. The sheer number of words available for sifting and savoring would explode—simply because people talk a lot more than they write.

With help from computers, you could trace quotes across speakers, or highlight your most common phrases, or find uncommon phrases that you say more often than average to see who else out there shares your way of talking. You could detect when other people were recording the same thing as you—say, at a concert or during a television show—and automatically collate your commentary.

2. Use it or lose it - One implication of not having to bother to remember what was said is that it could allow our brains to atrophy. Possibly.

In his book The Shallows, Nicholas Carr argues that new technology that augments our minds might actually leave them worse off. The more we come to rely on a tool, the less we rely on our own brains. That is, parts of the brain seem to behave like muscle: You either use it (and it grows), or you lose it. Carr cites a famous study of London taxi drivers studying for “The Knowledge,” a grueling test of street maps and points of interest that drivers must pass if they are to get their official taxi license. As the taxi drivers ingested more information about London’s streets, the parts of their brain responsible for spatial information literally grew. And what’s more, those growing parts took over the space formally occupied by other gray matter.

3. Does migration really help the economy? - Michael Reddell over at Croaking Cassandra has been doing some excellent work digging into the numbers and arguments behind New Zealand's surprisingly lax and high migration levels.

He has found that most of the migrants coming aren't nearly as skilled as we might think and the economic value they add is not as high as we all assume.

Officials explicitly recognise that large proportions of the people we give permanent residence approvals to (eg lots of family approvals) can’t really be expected to add anything much economically, and many represent a significant net fiscal cost. Officials note that a large proportion of skilled migrant category approvals are to former students in New Zealand, while observing that a large proportion of those have fairly low-level qualifications, and “we seem to have become less effective in retaining the skilled graduates we want”.

MBIE notes that “we are seeing a higher proportion of recent migrants (temporary and permanent) employed in industries with overall low or declining productivity. In particular, we are seeing temporary migration increasingly becoming a structural feature of the workforce – with certain sectors (eg dairy) increasingly relying on a ‘permanent pool’ of temporary migrant labour”.

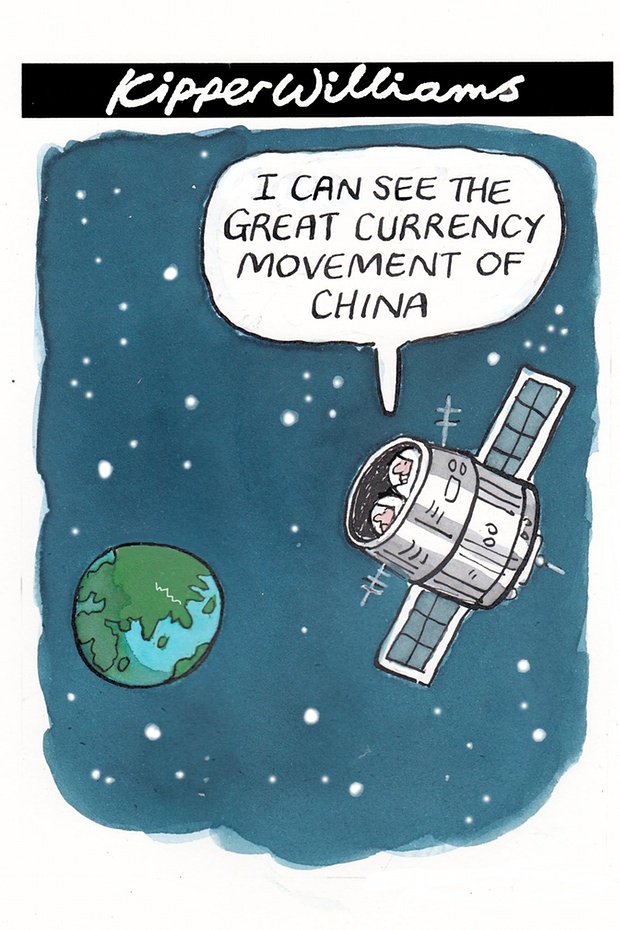

4. Capital outflows - The initial thought on hearing about China's stock market wobbles and the apparent slowing of economic growth there is that this will reduce the investment intentions of Chinese residents, or that they might hunker down and reduce investments in overseas assets.

It turns out it's doing the exact opposite.

The FT reports a survey it did of wealthy residents in China in July that found 60% said they planned to increase their overseas holdings over the next two years. Their first priority was to invest in overseas property.

With uncertainty rising at home, China’s rich have started looking elsewhere to store their wealth.

“China’s policy changes so quickly,” said a businessman in Shenzhen who would only give his name as Mr Huang. “I am worried about the safety of my wealth.”The survey found that 47 per cent of so-called high net worth individuals had earmarked more than 30 per cent of their assets for investment overseas.

The top reason for overseas investment, cited by more than 38 per cent of respondents, was to make it easier to get their children into good schools. As wealthy parents race to send their kids abroad to receive western education, many are buying apartments in college towns.

“The focus of China’s high net worth families has shifted from making as much money as you can to protecting your wealth,” said Shang Dai, chief executive of Kuafu Properties, a New York-based developer that draws funds from Chinese investors.

Many parents are buying properties to make sure their children have a slot at top schools.

5. The problem with driverless cars? - Cars with drivers. I'm excited about the prospect of driverless cars, but I wonder if they're really going to happen.

This New York Times piece looks at some of the challenges.

Google, a leader in efforts to create driverless cars, has run into an odd safety conundrum: humans.

Last month, as one of Google’s self-driving cars approached a crosswalk, it did what it was supposed to do when it slowed to allow a pedestrian to cross, prompting its “safety driver” to apply the brakes. The pedestrian was fine, but not so much Google’s car, which was hit from behind by a human-driven sedan.

Google’s fleet of autonomous test cars is programmed to follow the letter of the law. But it can be tough to get around if you are a stickler for the rules. One Google car, in a test in 2009, couldn’t get through a four-way stop because its sensors kept waiting for other (human) drivers to stop completely and let it go. The human drivers kept inching forward, looking for the advantage — paralyzing Google’s robot.

6. A third deflationary wave - Deflation and or low inflation seems endemic at the moment and this piece in the FT from FIdelity's Dominic Rossi argues the world economy is on the brink of a third deflationary wave as emerging markets slide. Last night's hints from the ECB that it will expand QE tally with this idea. Even 2.75% seems remarkably high for our OCR in this environment.

This third deflationary wave will mean that world GDP will continue to operate at a level below potential output. Downward pressure on prices will persist and a supply-side contraction in developing nations will be required before prices stabilise. A further fall in potential global output is now unavoidable. The adjustments to GDP forecasts are still ahead of us.

Consequently an economic landscape, formed of low nominal growth and low interest rates, will shape the developing world as it has shaped the developed world for some time. Those who hoped the secular opportunities of developing nations would insulate them from these woes will need to rethink.

Nor will a fresh round of competitive devaluations offer an escape route from these supply side adjustments. On the contrary, this would only intensify these price and volume shocks. A tightening of US monetary policy, and a stronger dollar, comes to the same thing. Either of these policy options would lower aggregate demand at a time it is already too low.

7. History does repeat - One of the big questions for those who think about global economics and New Zealand's future is whether China can avoid repeating Japan's mistakes.

We all remember Japan's astonishing rise through the 70s and 80s. Then its stock market and land markets crashed, heralding an era of stagnation that has lasted 20 years and is still dragging on.

Gillian Tett looks here at where China can avoid history repeating.

If you want to see what can happen when a government tries to prop up stock and land prices, Tokyo’s story is sobering. It shows that not only do interventions carry a financial cost (since they rarely work for long), but that they can be a lasting drag on investor psychology.

Consider the parallels. In the past two decades China has delivered impressively high economic growth by investing heavily to build an industrial export machine. This was supported by a bank-centred, state-controlled financial system that channelled cheap funding to favoured industries at the expense of consumers. The price of money, in other words, was set by autocratic fiat.

This is roughly what Japan also did in the decades after world war two (although such state control was more subtle and indirect in Japan than in China).

But Japan’s model changed from the 1970s onwards. As the country’s economy matured, Japanese companies had less need for bank-supplied cheap credit, and, as it grew wealthy, investors started hunting for places to put their cash. The government slowly started to move away from a bank-dominated, tightly controlled financial system towards something that had the trappings of capital markets open to the outside world. However, Japan’s pace of liberalisation was belated and uneven (if not downright arbitrary) and asset price bubbles developed as capital swirled around.

Monetary policy and exchange rate swings made the problem worse. So, by the end of the 1980s, stock and land prices had soared — in much the same way that they have in China, as Beijing has also tiptoed towards patchy liberalisation and embraced some capital market structures.

8. Trust is everything - Tett's conclusion was that Japan's bureaucrats who had tried to prop up the markets in the early 1990s eventually lost the trust of investors as banks who had not repriced assets at lower market levels eventually had to fess up in the mid 1990s. Stagnation ensued for 20 years.

By the mid 1990s share prices seemed to have stabilised at lower levels. But in 1997, when news seeped out that the banks were sitting on massive unrecognised losses (which later totalled almost $1tn), a financial crisis erupted, and asset prices slid. By that point, the system was also plagued by a pernicious lack of trust.

After a decade of (largely futile) meddling, investors no longer believed that Japanese bureaucrats were as powerful as they had seemed in the decades after the second world war. But they did not have much faith in “market” prices either, since everyone knew these were being propped up. Japan was thus in a limbo: the traditional pillars of faith that once supported asset values had crumbled, but there was nothing else to replace them.

Nobody really knew the “clearing prices” of assets, as traders like to say, or how far prices might fall if markets were free. Investors were haunted by an uneasy fear that bad news could seep that would push prices down again.

9. Totally John Oliver on Native Advertising.

10. Totally Clarke and Dawe - The anonymous leaker has a very shiny head....

38 Comments

#6 Even 2.75% seems remarkably high for our OCR in this environment.

Please feel free to firm up a justified rate to defer one's consumption today and offer the use of uncommitted funds to others wishing to participate in pass the bubble asset.

0.125% + core CPI sounds fair. (Insert mumvo jumbo about inherited wealth being nasty)

What's our uncommitted labour pool like?

I'm thinking if some of those opportunities opened to what the market serves, it would fill gaps that must, because of shortages, result in those value-add opportunities going unfilled.

Considering debt is rising (as servicing is getting easier), where is all the money going?

With no little disposable money left, what are the majority of people supposed to be buying these days? (apart from rates, power, phone, and insurance bills)

"where is all the money going?"

To our creditors - we have to borrow or sell assets equivalent to our current account deficit of around 4% of GDP. We haven't had a current account surplus since 1973 - forty two years and counting. During the GFC the government was the big borrower but the parcel has now been passed to Kiwi households, farms and businesses. Essentially, we are borrowing to pay the interest bill, if and when we get a return to more normal interest rates watch that CA deficit blow out. Lovely!

Simple, here is the justification. When ppl think they can make 15%~20% per annum for no work / production frankly a 10% OCR would not matter. In fact since no other business endevour would survive a 10% OCR it would be worse as there would be no other businesses left. End result a sure collapse.

The cure for this stupidity is just like the south sea bubble 100s of years ago, and what will happen, a financial wipeout and probably Govn bailouts and many decades of payback by the tax payer. Then ppl being bankrupt and having lost everything will then think like my grandparents and parents and avoid debt as they saw what happened to those that did not.

I worked in a NZ business that survived 15% plus interest rates in the late 70's early 80's as did most NZers my age.

The method of QE most of the world has been undertaking, seems unlikely to succeed at a global level at all. Reducing interest rates takes liquid income off the upper middle class (being those with savings accounts and term deposits) but increases the relatively illiquid wealth of those with shares and property. It is no particular surprise that this process does not materially increase consumption, which would be required for productive investment to gain any traction.

You sense that the QE undertaken by Japan and Europe, and to some extent China, is a competitive devaluation ploy mixed with a "lets grab as many foreign assets as we can for free" play. At a global level competitive devaluations will not increase consumption, although any one country not playing the game will find themselves asset stripped, or more in debt.

At some stage the main powers will revert to helicopter QE- direct funding of government deficits, which in turn will fund infrastructure, or tax cuts. Such QE will have a far more direct and positive impact on consumption, and get the world moving again.

At that point, New Zealand should undertake its share, endeavouring to keep the exchange rate and current account at a Goldilocks level.

Tax cuts sound nice. I take it this means that you are pro National with their tax cuts and anti labour with their ever increasing taxes?

Wouldn't need either if the govt had the gumption to collect what's really owed by the weathy ($6 B estimated by IRD) and the corporates.

Economically, if demand is less than capacity, then tax cuts would normally be an effective way to boost consumption. The most effective in this regard are almost certainly tax cuts at the bottom of the income stream, and so applying to all. I was referring to any country, but regardless, Is that National or Labour here? I sense National are a pretty much steady as she goes do nothing conservative government. And sometimes such a government is all you want. If change is ever required you would probably have to look elsewhere.

Note that infrastructure spending can be a similarly effective means to soak up spare capacity; and even Bill English has noted that NZ has a long list of infrastructure projects to undertake.

Is NZ currently working at way below capacity? Probably not materially; but there is a clear sense in the markets that some global wheels are falling off. If they do, and unemployment here ticks up materially, then there should be a combined fiscal and monetary response. The worst response is our time honoured one of selling assets or borrowing offshore to fund a lifestyle at times when we are not earning that lifestyle.

At some stage the main powers will revert to helicopter QE- direct funding of government deficits, which in turn will fund infrastructure, or tax cuts.

I posted a link earlier today claiming the BoJ is monetising more than the annual issuance of domestic government debt. How do you propose it should undertake a more direct funding operation?

I would hate to think you may be an advocate for something that might involve extinguishing the best rags to riches trade ever. It certainly made Bill Gross a billionaire just clipping the ticket of others money while he engaged the process on their behalf.

Stephen,

To the extent I have followed and understood your links, they prove my point. (So you and I are probably closer in thinking than either of us may have suspected; it's only at the solutions where I suspect we diverge.)

From your link, the Japanese have printed enough yen to buy US1.2 trillion of bonds from Japan's biggest pension fund (which for all I know is probably government owned, although that doesn't really matter). The pension fund has bought Japanese and foreign stocks with it. In other words they have printed their way to $1 trillion worth of free foreign assets, all the while keeping the yen down to boost local competitiveness. Smart for them; a problem for anyone else losing their assets and competitiveness. I note unemployment there is 3.4%. They are at capacity. But it is not through consumption. They are addicted to an export led model. There is very little about their current QE that would boost local consumption, and therefore inflation.

If the Japanese really wanted to cause domestic inflation, it would be relatively easy to do. Print money, and give it the people in tax cuts. But they are enjoying high employment, a good lifestyle, and buying up the world's assets. Why would they stop? Until the US or China tells them to, probably.

In other words they have printed their way to $1 trillion worth of free foreign assets

Every printed Yen remains a liability on the BoJ's balance sheet until the purchased securities are redeemed or sold.

I remain sceptical of the BoJ undertaking helicopter drops of YEN directly into the wallets of the citizen's at this juncture. Equally, any action in this direction would create a collective national liability demanding further sovereign debt issuance to redeem it. Hardly a winning trade. Read more

Stephen,

I have been known to be incorrect before, and may well be in this case, so happy to be corrected if that is the case. But it seems an important principle to be clear on, and here are the facts as I understand them.

Sometime in the past- probably over the last 25 years- the Government of Japan has issued debt to fund itself, and the Government Pension Investment Fund has bought at least $1.2 trillion of government bonds to help fund the government. Although the pension fund sounds government owned, it no doubt has real liabilities to pensioners, now and in the future. Nevertheless this was a debt from the government to the government.

Now, from your link, the Bank of Japan (the central bank) has bought back $1.2 trillion of these bonds, writing cheques to the Pension Fund of $1.2 trillion, out of printed money. The debt is now in theory from the government to the Bank of Japan (which is also the government). In the meantime the Pension Fund has had real cash of $1.2 trillion to buy local and foreign shares and property.

Am I missing something? The government of Japan has certainly no more debt than it had before, and in fact I would say less- the Pension fund had real liabilities, the BOJ has none. A debt from the government to the BOJ is not a debt at all. In the meantime they own $1.2 trillion more in assets, mostly foreign. And it all helped keep the Yen competitive.

This is international theft on a grand scale, and at some stage if no one else complains about the Japanese, we frankly should play our share.

The Pension fund has the same liabilities, half of which are now funded from assets that can move to zero value. The taxpayers have the same liabilities to service since the same value of JGB's remain outstanding and those who sold the risky securities to the GPIF have the cash. That cash is the liability on the BoJ's balance sheet and until it returns it remains, unless it is absorbed from the community by early government redemption of the BoJ's puchased JGB's. But that would defeat the QE objective.

The outcomes are not to be admired.

Non-regular employees rose to 37 percent of the workforce last year from 15 percent in 1984, according to the health ministry. As economic growth stalled, companies became less willing to hire full-time workers, turning instead to part-timers who are easier to lay off and often receive less pay and fewer benefits. Read more

#3. No. immigration does not help New Zealand.

Correct - 'no immigration' would not help NZ

# 11. US jobs numbers well down on predictions, but on a bright note their Labor Dept. said they would likely revise them up. Talk about having a bob each way - and some mugs actually take these stats. seriously! http://www.bbc.com/news/business-34154579

Good migration point. We are producing record numbers of grads, but the higher skilled they are, the more likely they are to leave overseas. Training lower -medium skilled nz ers ironically may be a better investment!

But for some lower skill areas, maybe we are too relaxed about temporary migration. The worse the employer/industry, the more likely they are to turn to temp migrants, rather than training and holding domestic workers.

Higher number of grads....

More often it is obtaining the trade/professional qualification that is the work prerequisite. And full time + student debt is not the only way to reach such.

We think there is/ has formed a bubble in the cost of uni education. That and mixed up with the value of residency.

As for immigration.where are all the phds the policy should be attracting?

Interesting UK perspective on the damage super low interest rates are doing:

http://moneyweek.com/how-super-low-interest-rates-are-ruining-the-econo…

What utter crap she speak.

Wow just wow....LOL

and these talking heads ppl listen to, interesting....dangerously so.

Super low interest rates encourage ppl to put money into things that may not be good investments, but surely the free market knows best?

In Auckland housing is currently paying 15% per annum? while running a real business, um no a few %. So if rates climbed, running a real business would be a total no while even at a 10% interest rate making 15% with 5% net for no effort still makes sense, until it goes wrong of course. the solves mis-allocation how?

I agree with her Steven...

Steven - there seems to be merit in each of the examples she has chosen. Rather than just call her crap, why don't you explain to us why she is wrong about each example (one of which, the shale oil bubble and the cheap debt used to finance it, made possible by ultra low rates, you yourself have ranted on about at length). We all realize you are in mortgage debt up to your eyeballs Steven but at least try and produce a coherent counter argument to each of her examples. I won't hold my breath.

Indeed

One day, someone here will attempt an explanation of how the NZ economy would behave if the RBNZ cut OCR interest rates by 2%, from 3% down to 1%

What would happen?

Who would be the winners?, and, Who would be the losers?

Give it a shot steven

What is clear is that savers with banks would be the losers as savings interest rates continue to quickly decline.

And those wanting to 'invest' and speculate in the Auckland housing market would be the winners with lesser interest to pay.

And those overseas with money to inject into Auckland properties would be able to ratchet up the property prices as the NZ $ declines and their money is worth relatively more.

And those who have resisted 'investing' in property may now evaluate whether it is time to get their money out of banks and into property - especially with OBR looming as the punishment for saving.

How this affects the overall economy is perhaps another story, but the short term consequence would be gasoline poured on the property bubble at the expense of anyone wanting to save money without becoming a property 'investor'.

The issue is when there is a substantial return ie 10%+ for no effort beyond borrowing, buying an asset and sitting on it just who is going to run a real business that struggles to make that. Yet those businesses are what counts, make the interest rates so high business gives up and that will be pretty ugly.

I dont disagree that this is crazy and wrong btw which is what I think it is your saying, just that raising interest rates will hasten an unwinding of the stupidity. Sadly I see no obvious way to stop this bar some sort of legislation which too many voters will not allow.

Borrowers would win and savers would lose..... in a country like Aussie or NZ much below 2% and you are pushing on string.... even if OCR was 1% what do you think business borrowing interest rates would be.... 5-6%? not much lower then now and you would find that while borrowing was cheap, it would be hard to borrow...... its an emergency setting.

I see 1y BNZ 4.3% ish can see a 3% handle pretty soon, looks to me like Aussie may lead us down here... its been pretty fast and loose in Aussie, residential investors have to stump up a massive 10% now I believe .. what could possibly go wrong?

“equity valuations appear high at a time when the outlook for earnings growth is poor”<\b>

funny this seems to be correcting nicely another 20% and we will be there maybe by end oct...

Indeed partially a long term RB policy disaster that has come to this, exasperated by successive do nothing as we dont want to lose votes Govns. When this pops, oh boy is this going to be unpleasant. I wonder how many ppl will be 'fesing up to their own greed and mistake(s) as opposed to blaming the Govn and everyone else. Or maybe I am wrong and we'll just keep growing for ever, no worries.

Modifying the OCR is a pretty well tried and true method of warming a slowing economy and cooling and too fast one.

The thing to point out is all else being equal. So if we stayed at 3% and we saw dis-inflation coming the "classic" action is to drop the OCR. The thing is to consider is the cause of the dis-inflation so over-powering that dropping the OCR slightly yas little effect. So the response has to be adequate for the size of the problem coming.

ie you dont use a peas shooter to stop an elephant you use something like a H&H375 or bigger (I dont hunt elephants)...

Winner and losers at what stage of the play?

Have a look at the Great depression, at the start the obvious losers were the stock brokers and financiers jumping out of windows, that didnt effect most ppl in main street initially. If you have savings in a bank, well look how many banks went out of business and ppl lost everything.

So the response of dropping the OCR is to avoid a recession and worse a depression where most everyone loses.

I terms of raising the OCR at the wrong time we have Sweden for how that didnt work and arguably NZ as well.

What else is there? for me to try and show you everything I have read? all I have listened to? for 9 odd years now.

So OK what do you suggest we do? raise rates? CPI inflation is already around the zero mark, the effect of raising will cost ppl jobs as the economy will shrink. If that happens what business invests and hence borrows off the saved?

What are you considering is a fair return on a deposit account? for almost no risk? (lets ignore the moral hazard of that for now) 7%? Surely then a business that has a considerable risk has to make your 7% back plus the bank margin 2%? plus then an actual return, what 20%? 7% for you and 11% for the business doing all the work and taking all the risk? is that really a fair split? cant say I see it as so.

Dont then.

and no you are wrong on all counts.

"And they know that the slowly accruing consequences of super-low rates are pretty nasty. It’s just that none of them want to go down in history as the guy who popped the great asset price bubble of the 2010s. Who would?"

um more like they dont want to be the guys and gals that caused a Second Great Depression. As the saying goes (paraphrase) those who dont know history are doomed to repeat it, and examples abound.

as I believe you have said before.

Stop it. I have told you before, you do not know what you are talking about and have never been in a position to do so. Your understanding of money stops at the gold coins jangling in your pockets.

Ah right I dont follow the Libertarian/mises/austrain school of economic thought so.......I dont know anything.

So really you dont like me disagreeing with you, oh dear.

Oh and I follow the likes of Paul Krugman and Steve Keen who most definitely have been there and have predicted this mess very well following Keynes and Minsky.

.

I am concerned the Silver Fern Farms is selling 50% for 100mil its like fonterra selling 50%, it seems nuts to me, for farmers to want to sell value added companies, isn't value add the place to be if you are a commodity chain....

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=115…

IT Guys - understand the state of Silver Ferns, surviving and rightfully under pressure from banks to improvng their falling equities levels over a number of years. Basically if NZers can't front with the cash, and thats obvious they can't or don't want to, and if you want to have a meat company or some value still left in it, invite anyone to provide that cash for you.

Commodity Fillet steak (regarded by some as the best) is typically $45 to $48 a kilo, Silver ferns so called value added sends the price the meat they sell to substantially above that like $62 a kilo. I suspect there is a feeling by consumers that there is value added and there is what ppl consider overpriced if not a ripoff. Now I have tried their products on occasion when its been discounted to the commodity price on the shelf and well, um no. ie sure there is value added but there has to be a real value, added. Not a bit of extra labour prep and a 30%+ mark up for a fancy bag and logo.

How long has the model struggled for and has been of a concern from watchers? So they are selling a stake, that is typically for 3 reasons? growth, realisation of value by investors and desperation. So is their business viable? How much debt is there? how much profit have they made? Will it be seen as a brave experiment or a misguided belief in marketing over value?

Well said billsay, and who will be complicit in the disaster that many can see coming, not only for those trying to survive on fixed interest, but the pension funds globally with contractual obligations that will drive either bankrupcy of public pensions, or bail-out and even more public debt and then MUCH higher rates when all faith in Govt paper is extinquished? - answer, including in NZ, central banks and the Govts pressuring them to bail out borrowers who are demanding even more record low interest rates to afford the over-priced assets that they alone have elected to buy.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.