By David Skilling*

The inflation trajectory, and the accompanying monetary policy response, is one of the big economic and market uncertainties for the year ahead. But beyond the near-term issues, the structural environment for inflation and monetary policy is also changing.

Double digit inflation provides a taste of some of the pressures ahead as economic and political regime change continues. Our 2023 outlook paper noted pressures for an ‘unravelling of the macro policy order’ as the global economy moved onto a wartime footing. The disinflationary environment of the past few decades is being replaced by new realities.

Transitory inflation

My basic view is that the inflation surge since 2021 was largely due to several post-Covid dynamics: global supply chain frictions; the strength of the rotation of consumer spending from services to goods; the exit of large numbers of workers from the labour force (either temporarily or permanently); as well as aggressive macro stimulus, particularly fiscal policy.

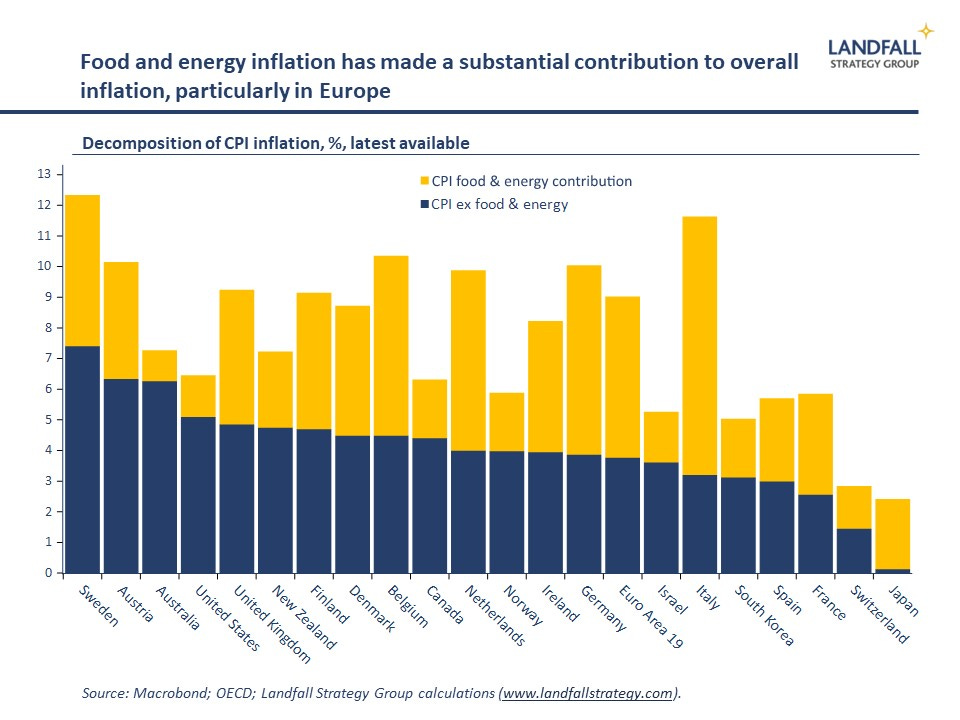

The severity of the supply side shocks, coupled with a strong economic recovery, led to multi-decade highs in inflation across advanced economies. This inflationary process was strengthened and lengthened by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: food and energy prices surged, particularly in Europe.

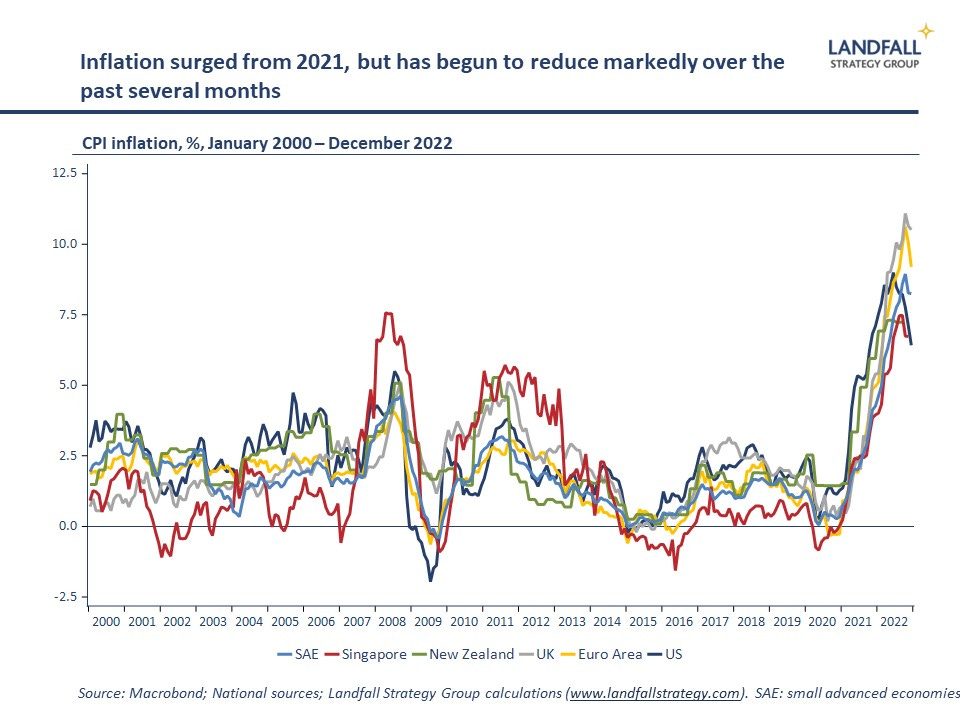

By extension, my view is that inflation will reduce as these factors moderate (I’m in the ‘team transitory’ camp). Indeed, many inflationary dynamics are currently unwinding: as noted last week, global supply chain costs are easing; food and energy prices are reducing; and consumer demand is rebalancing back towards services, removing a source of friction.

Inflation surprised on the way up, and it’s likely to surprise on the way down. Inflation has begun to reduce sharply from its peaks.

Core inflation remains well above target levels, but I see little evidence of a wage/price spiral or a meaningful de-anchoring of inflation expectations across advanced economies.

Tighter monetary policy is required to address inflationary pressures due to excess demand. But central banks need to be careful not to overdo the tightening response, using monetary policy to address supply side shocks (from energy prices to post-Covid labour markets).

Wartime inflation

However, at the same time as transitory inflation is coming down, other structural drivers of inflation are picking up that will lead to sticky inflation at higher trend levels than over the past few decades.

Over much of the past few decades, there has been a relatively benign inflation environment: the deflationary effects of globalisation; the massive expansion of the global labour force, as China and other emerging markets integrated into the global economy; positive demographics; technology; and so on. But many of these deflationary factors are either weakening or reversing, creating a less benign environment.

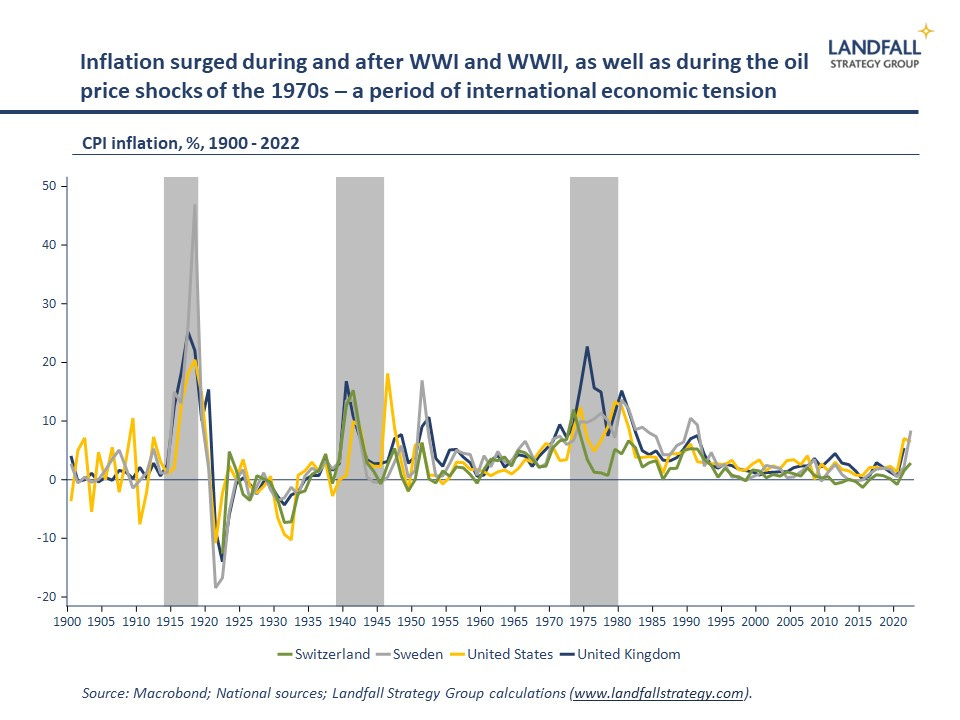

Beyond these factors, the inflation outlook will be shaped by the shift to a ‘wartime’ global economy. The economic dynamics unleashed in response to rising geopolitical tension will shape the inflation context: pressures for substantially higher government spending (increased military spending, industrial policy, the energy transition); more rapid economic decoupling in pursuit of strategic autonomy; increased supply chain frictions and risks; and so on.

History shows that periods of war, both hot and cold, tend to be inflationary. And although the ‘war’ is likely to be mainly economic rather than military, inflationary pressures will still manifest – particularly given the likely disruptions to a deeply integrated global economy. The Great Moderation and post-Cold War peace dividend, which provided the context for the inflationary environment of the past few decades are in the rearview mirror.

Trend inflation that is sticky above the 2% targets is more likely than not. The current inflation surge will moderate, but will be replaced by structural inflation pressures: ‘war by other means’ will mean expanding demand as well as supply-side constraints.

Policy debates

These dynamics will lend strength to several monetary policy debates. There are a few lines of active discussion that I have been struck by.

First, expect more focus on the inflation target. Keeping trend inflation at or below 2% in this environment will require increasingly tight monetary policy, which is not economically or politically sustainable. There is already an active debate about whether a higher target – say 3% – may be more appropriate. As inflation remains sticky above 2% over the medium-term, this debate will intensify.

Second, the recent experience of countries has highlighted the use of non-monetary levers. France, for example, has used (government financed) price caps on energy bills to control inflation. On some estimates, this has reduced headline inflation by ~3%. Other countries have also implemented price caps, imposed windfall taxes on profits, managed wages through tripartite arrangements, released strategic petroleum reserves, and so on.

There is an increasingly active debate on strategic price controls (Isabella Weber) as well as on the use of non-monetary policy levers (Olivier Blanchard and Paul Krugman). Structurally higher inflation will provide impetus to this debate, as has been the case in previous wartime situations.

And third, growing political debate about the extent of central bank independence is likely. Central bank independence was one of the institutional markers of the emergence of the new policy regime from the late 1980s/early 1990s, and will come under pressure in a new global strategic context.

The government’s growing borrowing requirements as spending demands increase – from military spending and industrial policy to the net zero transition – will create a need to find buyers for this debt. Pressures for ‘fiscal dominance’ will grow in some economies as governments require/encourage central banks to provide greater fiscal space (low rates, buying government debt, and so on).

Monetary policy is not immune to political realities. As discussed in our 2023 outlook note, if policy institutions are in tension with changing strategic priorities, it is likely that it is the institutions that will give. Inflation is importantly a political phenomenon, and monetary policy will be subject to political influence.

What this means

Significant changes are likely in the operation of monetary policy. Nominal interest rates will continue to increase, as we move away from the QE environment implemented in response to below-target inflation. Indeed, negative interest rates have all but disappeared from the global economy: with Japan the latest to move above the zero threshold.

But the more accommodating monetary policy stance - a higher inflation target, increased reliance on other instruments to control inflation, and perhaps a measure of financial repression - means that policy rates will likely be lower than would otherwise be expected given higher inflation.

So expect higher trend rates of inflation, as a consequence of changing global economic dynamics, government responses to strategic competition, as well as more accommodating monetary policy. My guess is that inflation will be controlled, but that there will be greater comfort with inflation in, say, the 3-4% range.

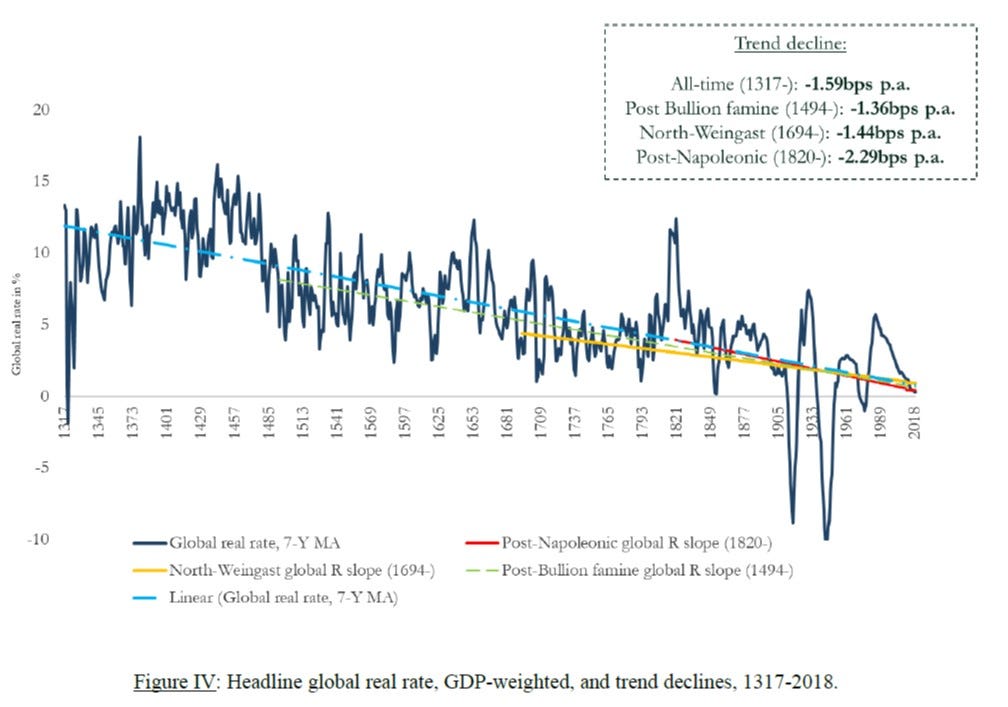

Together, this means that real interest rates will likely remain under downward pressure. [As an aside, this is consistent with the very long term negative trend in real interest rates documented by striking Bank of England research!]

Monetary policy will adapt to new global economic and political realities. However, this transition will be bumpy, with experimentation, policy lags, and over/under-shooting. And not all economies will move at the same speed: small economies, which have fewer degrees of policy freedom than large economies, are likely to follow not lead. Although I think there is clear direction of travel, there will be turbulence ahead.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

**Get in touch (by reply email or at contact@landfallstrategy.com) if you would like to access the full paper referred to in the article above.

28 Comments

Good article! People have a tendency to extrapolate what is happening forever.

And very poor understanding of economic forces led current government to exponentially expand the inflationary affect by its multidude of policy mistakes hammering business supply side of the economy.

If you make it so difficult for such a wide range of businesses to operate freely, from self imposed labour shortages, to silly endless regulations and compliance costs and restrictions, that simply and amazingly restricts the amount of supply and the cost of supply.

Do that while demand is bouncing back from Covid and people are coming back to country, its 101 Economics, massive price increases accross the board.

Good article. I am also in Team Transitory.

I am firmly of the view that the Ukraine War extended this inflationary phase much longer than we would have otherwise experienced.

There will be turbulence ahead and some might not be able to digest it and puke.

We need a reset and this is probably the right time for a reset.

Additionally all the leaders in the world are acting childish at the moment.

Fighting with each other solves nothing except making a few rich nations more richer who have their whole economy based on selling military hardware to others.

How can 7-8 billion of world population sustain itself by isolating each other. There is a big mismatch in the world with a few nations having huge amounts of resources. World can never progress by isolation, it can only by co-operation.

Centuries of history suggests that "fighting with each other" significantly reduces population pressures because a lot more people are dead & life expectancy is severely diminished. 100 years ago the world population was 1.8-2B, roughly a quarter current. Even after WW2 it was only 2.5B, Its the relative peace & cooperative prosperity since thats trebled the population & resource demand.

I love the use of the word transitory. 6months, a year, two years, five years. Never really defined with a time scale and the reason for selecting a particular time scale.

Only a transitory recession.

I think we would have been back to inflation of circa 3-4% if not for the war.

it will be down to that sort of range within 6 months as our economy slumps big time. Supply side inflation might keep it up around 3.5%, even if demand side inflation is dead and buried.

Historians also use the word transitory to describe the brief period of 160 million years that dinosaurs walked the Earth.

I think the word flux is better than transitory.

If anyone remembers, at the start of covid beef got really cheap, because hospo wasn't buying any and less was exported.

That sends a message to dry stock farmers to breed and raise less calves.

Now things are picking up, and there's less cows of the right age. So prices increase. Maybe farmers are raising more stock, but then the economy also isn't looking flash. And inputs are now more expensive, no labour, etc.

Takes 18-24 months to raise a beefie, sometimes more.

Multiply this by every other sector of agriculture and you can see that the 'transitory' state will take years.

What a great article David, I have rarely read an article I agree with so much.

1) Yes, there is a transitory element to inflation which is starting to reduce now, people dismissing some inflation as being transitory, because it lasts one year, don't understand that CPIs are measured on a yearly, comparative basis.

2) Yes, there is a basic structural change for higher inflation for the reasons you have given

3) Yes, the central banks won't be able to bring inflation back down to current targets, most being 2% (I have stated this multiple time) and central banks WON'T be able to raise rates until inflation reaches target of 2% (because it will cause too much damage to the economy). Therefore, and this is the central point IMO, as I have stated before, there will at some stage, be a readjustment upwards of what the target inflation rate is. Around 4% would be my best guess.

4) In terms of interest rates, I believe this will mean that in 1 - 3 years time, they will drop from their current highs by about 2% to stabilise at about 3 - 5% for retail interest rates.

It’s difficult to predict, however I’d suggest a target of 3% inflation would have retail rates a little higher than 3%. I imagine the ocr a little higher to keep downward pressure, and retail rates 1-1.5% above that. There is a lot of spending power to wade through, so an eventual “settled” period where retail rates are 5-6% maybe? Slowly trending down. Who knows how long that lasts but would mean the next cycle would hardly be as dramatic as the current mess

Well put.

Also, They won’t need inflation to be down to 3% to justify OCR cuts. Employment and financial stability are key parts of their official mandate. Both will be tested, and rising unemployment in particular will allow them to cut the OCR, provided inflation is back around 3.5-4%.

The kind of commentary that I come to this site for!

Something people don’t talk about much is the impact of bonuses on the economy. They have been pretty good last few years but not likely to be As common or as much this year.

Together, this means that real interest rates will likely remain under downward pressure

Typically this should be bullish for assets like gold and silver. But we know that the Western ruling elite have been actively suppressing the price of gold -- something that the BRICs appear to want to end.

Looking forward to a transitory 6 to 8 % increase in the NZ super this year.

Well just bought some pure pork sausages from the butcher now $20kg and a few months ago were $16. The inflation is NOT transitory because the effect of it is permanent. Unless prices actually start to fall then inflation was not temporary and transitory implies it was just a blip, well its no longer a blip.

"The inflation is NOT transitory because the effect of it is permanent. Unless prices actually start to fall then inflation was not temporary"

I understand your statement Carlos, but I think it's incorrect. By your example if your sausages still cost $20/kg next year, then there is no more inflation, hence the inflation over 2022, from $16/kg to $20/kg, can be called as transitory. The price of goods or services doesn't need to return to its original level, in order for inflation to be transitory.

Inflation measures the price increase, not the price per se.

If David had any skill at predicting the future he would work for a hedge fund rather than a consultancy.

Poor comment JB, no need to attack the writer based on his employment. Also I think his article above is very pertinent, I guess time will tell how correct his predictions are.

Disgusting comment. Completely uncalled for. House Mouse does this too. Attacks the writer of the article. Low self esteem perhaps. You know the people who write these articles read the comments. Our recently departed PM complained about this kind of stuff, and a lot worse. It needs to stop. Perhaps Interest.co.nz could set a high bar with this, zero tolerance?

Which article writer have I attacked personally? If I have, very rarely.

If Javaboy made good posts his account would last longer than a couple of weeks.

David is a sought after financial consultant , with his own company , and offices around the world ...

... you have ? ... perhaps your own mop & a bucket ....

Have to say I agree with a lot of this - despite my negative comments on this author's articles before (sorry). Key point here for me is that price increases are happening because it is getting more expensive to produce some goods or provide some services. No need to panic! If getting product X from A to B to provide service Y now requires 50 hours more labour, and more money for the Saudis selling oil, then the resultant price is the new price - suck it up. Adjust. As wise people have said before... the best cure for inflation is higher prices.

Or lower expenses.

Once (or if) the economy hits the skids, those with the most inflation adjusted pricing (or wages) might find themselves out in the cold.

A few things not mentioned in this article that I think should be considered as being less transitory.

De-globalisation, manufacturing leaving China?

De-carbonisation. There is a big step shift begun in electrifying vehicle fleets around the world. Here in NZ we are going to pay for this by planting pine trees (or overseas investors are at least?).

Infrastructure deficit. For example, regardless of where 3 waters issues as an example get fixed from, they have to be paid for and across the country many councils are in the same boat and at the same time. Power distribution is probably the same. We all see daily the decline in roading infrastructure. We'll all be competing for materials and expertise to fix these things at roughly the same time.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.