By David Skilling*

‘War is a mere continuation of policy by other means’, General Carl von Clausewitz.

As we end a turbulent 2022, I have been thinking about what firms, investors, and governments should be positioning for in 2023 (and beyond). This year, together with Mike O’Sullivan (long-time collaborator and Landfall Strategy Group Senior Advisor), we have prepared a paper on key dynamics that will shape the year ahead.

This note sketches out our view on these dynamics.

2023 is likely to be another volatile year. This ongoing turbulence reflects not just idiosyncratic shocks, but also a regime change in the global economic and political system.

After the end of the beginning

Our core thesis is that the global economy is moving onto a ‘war time’ footing, with increasing, broad-spectrum strategic rivalry between the big powers reshaping the global economic and political system. The key domains for this strategic competition relate to economics, finance, and technology – extending well beyond military competition.

Increasingly, government policy across multiple areas will be deeply shaped by this strategic competition, from macro policy to industrial policy and the net zero transition. In turn, economic outcomes, the business environment, and markets, will also be affected. 2022 was the ‘end of the beginning’ for the new regime, and these realities will powerfully shape 2023. The global economy has been relatively depoliticised – but politics is firmly back.

Previous episodes of regime change have had big impacts on investment returns, profitability, and national outcomes. New approaches are needed to prosper in this new context.

We identify five major themes associated with this regime change and their implications for firms, investors, and policymakers: from a changing globalisation model to the return of the state and changed macro policy settings.

Globalisation & strategic autonomy

Although the death of globalisation is exaggerated, globalisation is changing in structural ways. Economic factors are partly responsible, supporting reshoring and nearshoring. But domestic politics and geopolitics are much more disruptive factors in reshaping global flows.

In domestic politics, there is a growing push for strategic autonomy and independence in key sectors. Industrial policy has crossed into protectionism. The Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act in the US are two examples, with sweeping local content provisions. The EU and numerous national governments are likely to respond with industrial support packages of their own through 2023. And China will continue to strengthen its development of national champions.

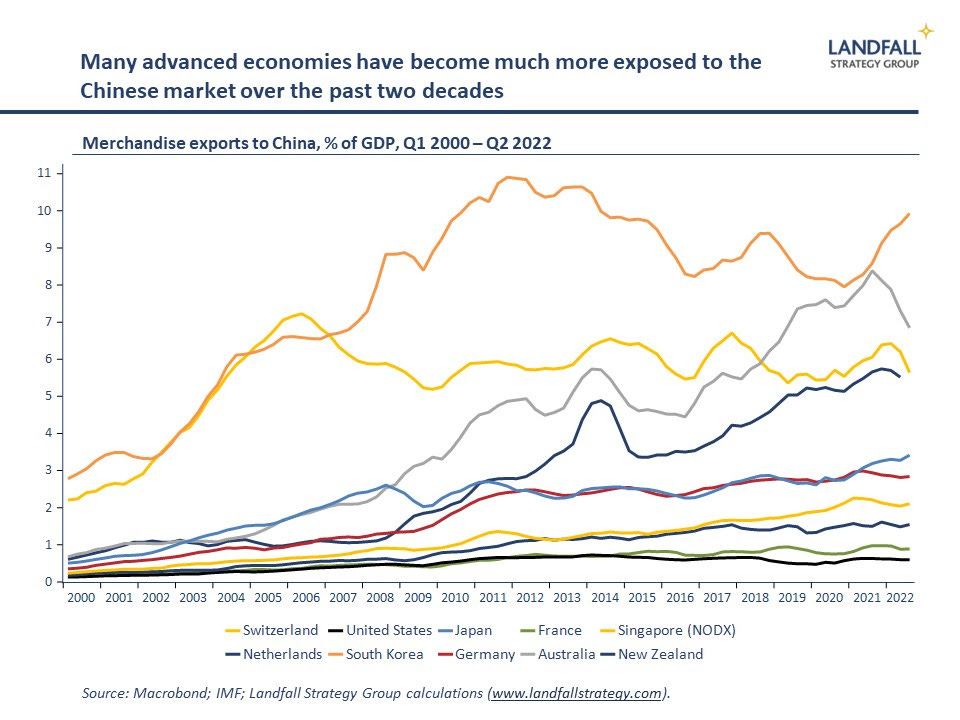

Relatedly, growing geopolitical rivalry between the US/West and China will powerfully shape global flows. The US has imposed restrictions and sanctions on China, notably on semiconductors, and is looking to decouple parts of its economy. Similarly, Europe and others will continue to reduce economic exposures to China, albeit in a more gradual manner. China’s policies also push in the same direction – reinforced by observation of Western-led economic sanctions on Russia.

2023 will be a year in which we move into much more explicit political competition and tension in globalisation, with a more fragmented global economy emerging rapidly. The recent G20 meetings put some guardrails around the US/China relationship, removing some of the tail risks, but the logic of strategic competition remains intact. Firms and countries will need to make deliberate choices.

The return of the state

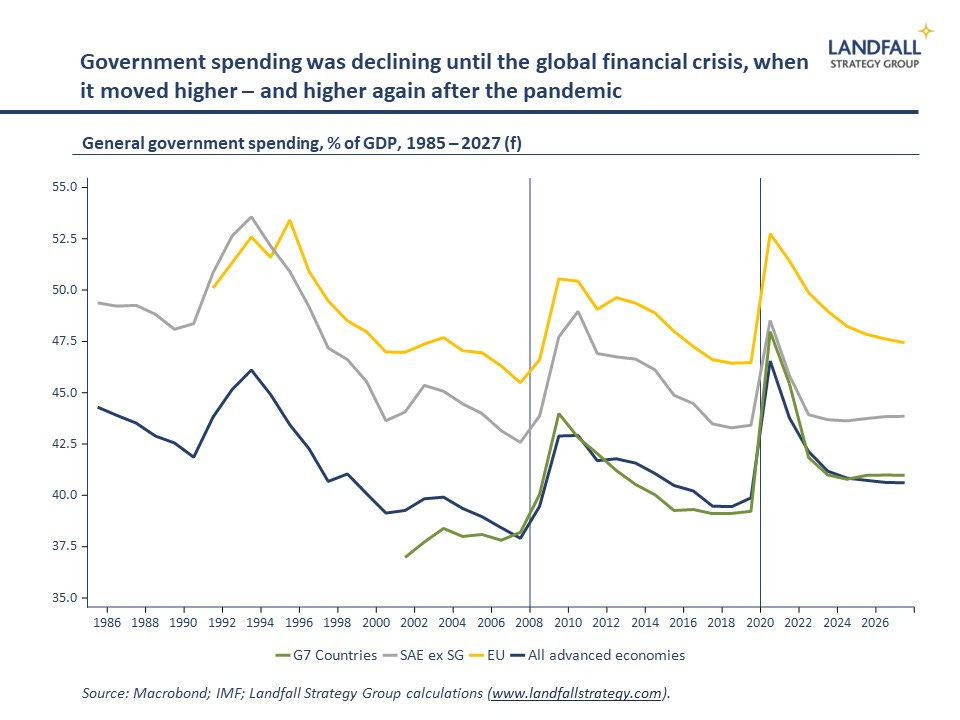

After a few decades of declining government spending, interrupted by the global financial crisis, the size and role of the state is expanding. The pandemic and energy crisis support packages reflect changing expectations on the role of government and will be difficult to reverse, particularly into a slowing economy.

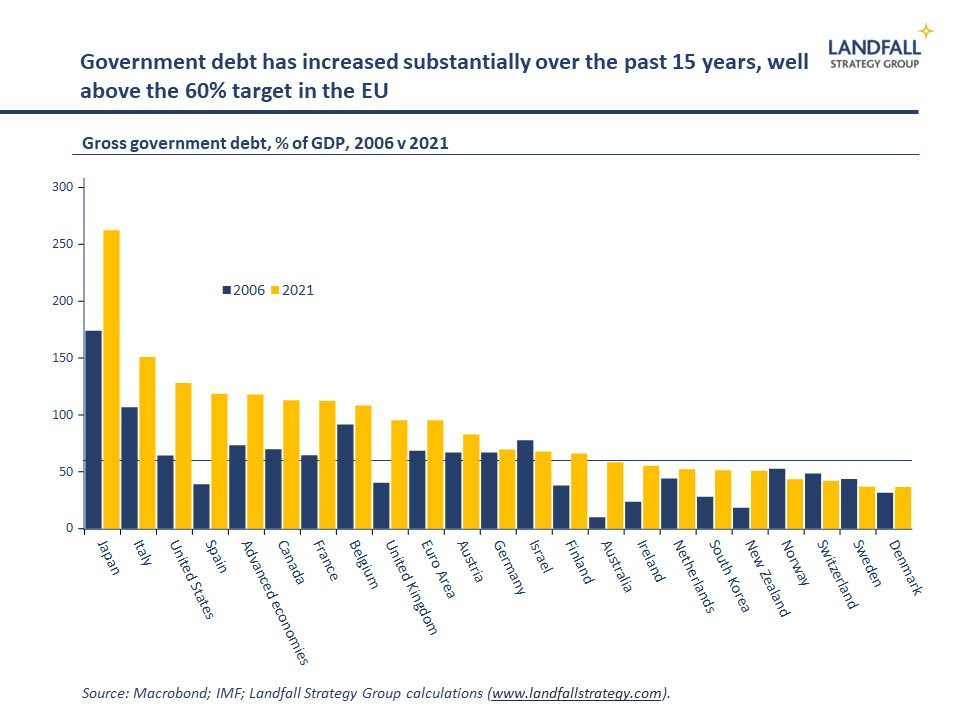

And beyond the pressures for transfer payments and the costs of an ageing population, strategic competition will lead to increased government spending. Many governments have committed to raise military spending to 2% of GDP (or more); significant investments are being made in the net zero transition; and there is increased spending on industrial policy initiatives.

Beyond financial support, governments will also take a more expansive role in trade and regulatory policy to support key strategic sectors and building national champions.

There will be pressure to increase tax revenues to fund this spending. Wealth and asset taxes will become more prominent, together with windfall taxes and higher corporate taxes. An increasingly progressive tax system is likely. Efforts to reduce international tax competition, such as the OECD’s minimum corporate tax rate agreement, are consistent with this.

Given the magnitude of the likely increases in government spending and investment, the quality of those decisions will make a substantial difference. State capability will become a core driver of national competitive advantage.

Democracy fights back – and the autocratic recession

The strategic competition between big powers has sometimes been framed as democracy versus autocracy. This is not an entirely accurate framing, but it does capture something. As some Western political systems have stumbled over the past several years, they have often been compared to apparently high-performing autocracies like China.

Yet as we look into 2023, democracies are on the comeback after a period of ‘democratic recession’. The centre is holding and populism is broadly on the retreat. Across Europe, reasonably centrist parties are in dominant positions. The US remains deeply divided, but the centre is also stronger. This dynamic is partly because democracies have been responsive to popular preferences through challenging times (Covid, energy crisis); and it may be that the increasingly evident strategic competition has led to greater seriousness.

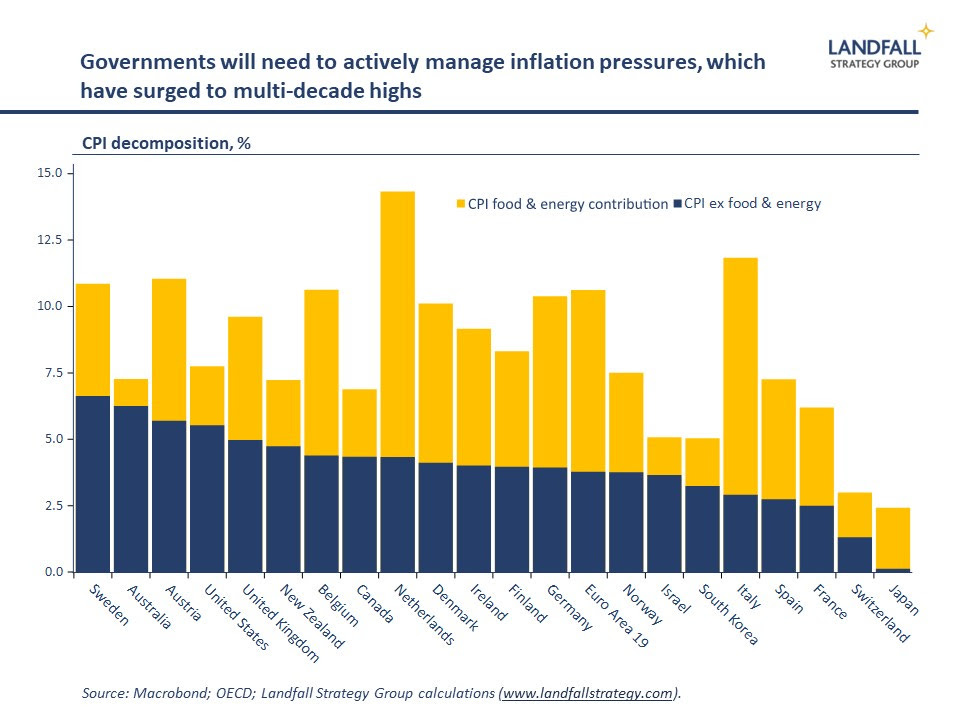

There are of course challenges to democracies. One of the biggest challenges in 2023 will be managing the redistributive implications of high inflation: real wage growth is negative, household budgets are squeezed and borrowing costs are increasing. High inflation is weighing on public support for governments.

In contrast, an ‘autocratic recession’ is more likely. China will face major political issues through 2023, most notably getting out of the Covid corner it has painted itself into. And the Chinese economy is slowing structurally, with increasing youth unemployment. Iran is struggling with poor economic and social outcomes and political discontent. And the Russian economy is likely to struggle to a much greater extent in 2023.

China, Russia, and other autocracies were on the offensive over the past decade, sensing democratic weakness. But democracies now have more reason for confidence in their model.

Macro unravelling

Strategic competition will also contribute to an unravelling of the macro policy order.

We expect inflation to drop in 2023 but to remain stubbornly above target – including for structural reasons, such as frictions on globalisation and higher government spending. As a result, interest rates will also remain at a high plateau. This will create a range of macro risks, as pressure is placed on leveraged parts of the global economy.

At the same time, the shift to a war-time economy will challenge the current macro policy regime: fiscal rules with a focus on fiscal sustainability, and independent central banks with a price stability target. Higher government spending and investment will run into the constraints of fiscal rules and central bank inflation targets.

If the choice is between strategic priorities and existing macro policy institutions, it is likely the institutions that will give. There will be a shift from policy rules to policy discretion: a relaxation of fiscal rules and softer inflation targets, perhaps with diminished central bank independence. QE will be difficult to end. Higher trend inflation is likely as macro policy remains accommodating.

By way of analogy, the US decision to unilaterally exit the gold peg in 1971 was due to the tension between its strategic policy objectives (domestic spending, the Vietnam and Cold Wars) and macro policy rules. Similar pressures will become more evident in 2023.

The USD will remain dominant, but there may be some changes in the global financial system. As one example, it seems unlikely to us that the HKD peg can be sustained given the rivalry between the US and China.

The commanding heights: the technology & energy revolution

Technology is commonly thought to dominate the commanding heights of the global economy, and national economic policy is often focused on developing an edge in technology. China, the EU, the US, and others, are increasingly investing in strengthening strategic autonomy in leading technology sectors. Through 2023, we will see increased government capital flow into strategic areas of technology.

Economic sanctions and restrictions are being placed on technology flows and investments between the competing blocs – and this will strengthen through 2023, drawing in a broader range of countries. Choices will need to be made. There are costs to global economic fragmentation due to the push for strategic autonomy. But as in other domains, competition between countries can be a good thing – creating sharper incentives for investment and innovation (as during the Cold War).

In addition, energy remains a core element of competitive advantage. The US is advantaged with its high measure of energy independence relative to Europe – which is currently facing competitive pressures, particularly in energy intensive sectors.

Energy investments, particularly renewables, will be accelerated in 2023 for several reasons: in response to the current high prices and supply concerns; as a matter of industrial policy; to comply with net zero targets; and as a matter of strategic autonomy. Economies that can rapidly move to renewables (electricity, green hydrogen) will be advantaged.

Those countries and firms that can combine technology leadership as well as security of supply of critical flows of commodities and energy will out-perform. As technology and energy are increasingly framed in strategic terms, the pace of change will increase markedly, generating significant investment opportunities.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

**Get in touch (by reply email or at contact@landfallstrategy.com) if you would like to access the full paper referred to in the article above.

19 Comments

A fairly good summary.

The West is sort of eating itself, getting lost in culture wars and Red Team vs Blue Team, aging, losing chunks of its manufacturing base, but our information apparatus known as the 'news' has a commercial necessity to sell us on hysteria. It does seem like Putin has watched too much Fox News and overestimated how weak the Western alliance is.

Regardless, this country needs more strategically minded leadership. We've conducted 3 decades of neoliberal economics, but a large amount of that seems to be totally dependent on debt, and open and unrestricted global trade. Maybe we shouldn't take that of as much of a given.

At the same time, the shift to a war-time economy will challenge the current macro policy regime: fiscal rules with a focus on fiscal sustainability, and independent central banks with a price stability target. Higher government spending and investment will run into the constraints of fiscal rules and central bank inflation targets.

The shift to a war-time economy - really? NZ cannot afford hospitals, how will weapons fit into the struggle for infrastructure expansion.

At least we have the refinery for fuel security......

Exactly - US Security Strategy’s Empty Narrative

The war time economy for NZ is Europe first, NZ second. Not actual weapons but other economic shoot yourself in the foot.

Europe has it's own problems:

The Yellow Vests at 4 years old: their 3 greatest historical achievements

Pretty sure most Demons would creep up from the basement, if they are coming down from the attic you are already in Hell.

It's be great if the government made a sarin soman tabun factory. At least then I'd have a job here. Doesn't seem like a labour / green initiative, and to be honest weapons seem like a zero sum game in terms of wealth creation. I guess if you’re exporting them it’s okay.

"We've conducted 3 decades of neoliberal economics, but a large amount of that seems to be totally dependent on debt, and open and unrestricted global trade."

(From above, and it was supposed to be Replied to!)

Well put. And along those line, from Mauldin this morning:

Federal Reserve policy has been the bull’s best friend for 20 years now, and maybe 40 years if we count since Volcker and the Greenspan Put. It’s easy for people who made a lot of money in these conditions to convince themselves that higher rates and QT are aberrations that will surely end soon....I suspect we are going to need a new vocabulary to describe the 2020s economy and beyond. It has been, and will remain, unlike anything we have ever known or seen

Totally we are very distorted here, so much investment only works if your cost of funds is only 2-3%, its worth noting that historically once inflation reaches 5% it can take a decade to get it back to 2%, we are seeing that pressure in NZ pay settlements now. Together with de-globalisation base cost of funds is probably 2-3% higher then it was , add in green energy costs... we could see a base global rate of 5% for a long time here as all the mis allocation of investment unwinds.

Got to like Gold here IMHO for the next 10 years.

Renewables to run the big US, EU and Asian grids is magical thinking: the Europeans first have found wind and solar simply isn't reliable enough for a grid's base load, and basing your gas requirements to meet the gap on your enemy wasn't that smart while you virtue signal 'green', thus renewables were malinvestment for the highly populated sectors of the world: the future green has to be nuclear for those big populations, esp once Centrus Ltd demonstrates the first generation small reactors next year in US (under contract with US Govt) running on HALEU. But to fill the gap in the meantime, they will require a lot more gas (LNG) especially, oil and coal to get them through than there will be supply for. With US petroleum reserves on a 36 year low, this round of WEF clone Western governments, Ardern, Trudeau, all the EU governments almost and Biden don't seem to have the ability to think even medium term strategically for their own survival. And with a militarised China and Russia, and growing India dependent on them for energy, there are dark times coming for the so-called free economies of the West (albeit, Ardern, Trudeau, etc, have used Covid emergency powers to destroy freedom in the West anyway, so there's not much left of hope. Eg, Ardern has legislated co-governance unconstitutionally under an unnecessary urgency so there could be no debate, or at least that's what the all powerful Maori caucus learned from Covid: legislation under urgency = autocracy under Mahuta-corp).

We're stuffed, but if oil ever gets back below $60brl US first quarter of next year, buy hydrocarbons for medium term and nuclear long term. The real problem for Kiwi investors being the USD will start going into permanent decline once the Russia/China/India bloc deliberately delink from USD mid 2020's to trade based on the value of the commodities they extract and hold within their own countries. (Oh yeah, buy resources/commodities, esp copper and the rare earths, from about mid next year - or now if you don't mind taking a bit of a loss short term).

It's all easy, looking back. Where we go from here is all that matters.

Former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown expressed regret at not implementing tougher regulations during his tenure of chancellor between 1997 and 2007, responding to "relentless pressure" from the City not to over-regulate. We know in retrospect what we missed.....We didn't understand how risk was spread across the system, we didn't understand the entanglements of different institutions with the other and we didn't understand even though we talked about it just how global things were, including a shadow banking system as well as a banking system.That was our mistake, but I'm afraid it was a mistake made by just about everybody who was in the regulatory business.

The UK Financial services are desperately trying to go back to the future

UK banking rules in biggest shake-up in more than 30 years - https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-63905505

Hmmmm..

”Behind it all lies the City of London, anxious to preserve its access to the world’s dirty money. The City of London is a money-laundering filter that lets the City get involved in dirty business while providing it with enough distance to maintain plausible deniability . . . a crypto-feudal oligarchy which, of itself, is. . . captured by the international offshore banking industry. It is a gangster regime, cloaked with the “respectability” of the trappings of the British establishment. . . . guaranteed protection. No matter just how nakedly lawless their own conduct.”[20]

“The City is often now described as the largest tax haven in the world, and it acts as the largest center of the global tax avoidance system. An estimated 50% of the world’s trade passes through tax havens, and the City acts as a huge funnel for much of this money.”[21]

Here is an important website that contains many links related to the City of London and its use of tax havens to launder money.[22] Link

Brexit locked this in place.

Audaxes,

Well said. Nicholas Shaxson wrote about this in his book Treasure islands. The Finance Curse also by him is well worth the effort.

The article looks to me like a pretty good take on the forces at work.

"Those countries and firms that can combine technology leadership as well as security of supply of critical flows of commodities and energy will out-perform. "

Well, NZ should do really well then, given that we are so centrally located, energy independent, have easy access to all the resources we need and are pushing back the frontiers of science and tech every day.

Rob,

"energy independent". Where on earth did you get that idea from? You do know that we import almost all our petroleum based products don't you? And now that Marsden has closed, we are even less secure than before.

":have easy access to all the resources we need and are pushing back the frontiers of science and tech every day." I suggest that you look at the stats for what we import. Then you wouldn't write this sort of nonsense.

I don't always agree with David but this article is quite sound in its theory. The big issue for me is trust, or the lack of it, both in its macro & micro form. Hard earnt & easily lost, trust is up for grabs as the 2020's unfold. Politicians have basically lost the trust of the people they govern, which was always the case in many countries, but is now coming very obvious within the democracies, unfortunately. What's better than a democracy you ask? I don't have the answer on me, but we better figure it out. And fast.

America is in for a big shake-up with the FBI now exposed as an extra arm of the DNC. This will blow next year & will be very interesting to watch unfold. American leadership is as bad as anyone's out there, but their systems are still very robust (in global terms) & if anyone can weather a storm, they can, as history has shown. The Yanks like to fight, even amongst themselves, so life with a GOP majority Congress & DNC President will be explosive (I'm picking). Sadly, the west is losing the battle from within, as the elite liberals slowly strangle everything & everyone, however, its very hard to hide these days & if any system can fix itself then its the democracies.

China has now picked all the low hanging fruit. From here on they will need ladders to reach higher for tomorrows lunch. Once again, the leadership is corrupt & like their commie cousins did (still do?) in Russia, back it up with many levels of state brutality. If the CCP can avoid a date of disaster with its own people (a Chinese civil war) then they might do quite well for a while. Longer term(?) the corruption will get them as it always does.

Europe will need to toughen up if it ever wants to remain at the top table. They still believe that they are at the centre of the universe but EU socialism is cooking the goose slowly but surely. No tourists, no income, especially since the energy crisis has hit. They need to get Russia back inside the building before China makes its move north, as without all that cheap energy Europe is going nowhere.

And life down under? I'm picking a new order of South East Asian human energy combined with all this part of the planet's natural resources to create something a bit different going forward. The Euro-Asian mix was always a perfect match, as Hong Kong (& Singapore) testified to for many decades. I'm suggesting that this combo will be very competitive as a future global partnership. I also think that the Yanks will see this & want to buy in as well, which would be almost unbeatable on paper. I just hope I'm right.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.