By Lisa Marriott & Edward Willis*

If you look at the justice policies of the main political parties you’ll see references to gangs (ACT), violent criminals (National), greater investment in policing (Labour), social justice (Green Party) and problems with the criminal justice system (Te Pāti Māori).

What you won’t see is any reference to white-collar crime. This could perhaps be because New Zealand doesn’t have a lot of it. But a more realistic view is that we don’t invest in detecting, deterring or punishing white-collar crime. We don’t even really talk about it.

Take cartels as an example. Cartels are essentially where two or more businesses agree not to compete. This affects competitive markets and hurts consumers, causing increased prices (via price fixing) or decreased supply (by restricting output).

But cartels are notoriously difficult to detect due to an absence of formal arrangements and their inherent secrecy.

Leniency for whistleblowers

Cartel activity was criminalised in 2021 in Aotearoa New Zealand. Anyone found guilty can now face a prison sentence, along with substantial financial penalties.

However, the rules offer generous leniency and immunity provisions for cartel participants who reveal the existence of the cartel to the Commerce Commission. The commission won’t take legal action against the whistleblower if they cooperate in the prosecution of the other cartel members.

The aim of these provisions is to destabilise cartels by encouraging whistleblowing. They serve as a deterrent because they make joining a cartel riskier by increasing the likelihood of getting caught. Requiring the whistleblower to cooperate in a prosecution increases the likelihood of successful cases due to the evidence that can be presented to the court.

Along with this leniency, the whistleblowing firm may remain anonymous and not suffer the reputational damage attached to other cartel participants. The disclosing individual or firm also retains all the benefits of the offending.

Where a firm is involved in cartel behaviour, any leniency or immunity granted is typically extended to directors, officers and employees involved in the conduct.

By the numbers

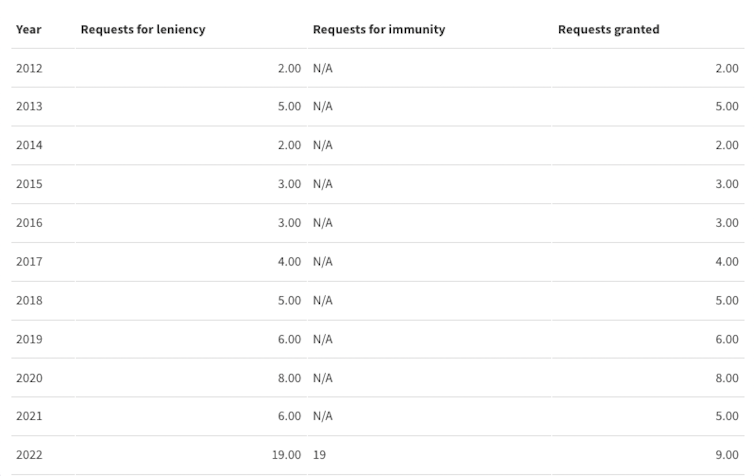

Such provisions have existed since 2004. Before criminalisation in 2021, leniency was automatic for self-reported cartel activity where there was no existing investigation, if the whistleblower met certain conditions, including admitting and stopping the bad behaviour and providing evidence for any prosecution.

Since 2012, 106 firms or individuals have been charged with anti-competitive conduct.

Our data shows an upward trend in leniency applications and a significant increase in applications for leniency and immunity in 2022 after criminalisation. Requests for leniency averaged 4.4 per year prior to 2022 but increased to 19 in 2022. We found that 43 of the 44 requests for leniency prior to 2022 were granted, while nine of the 19 requests in 2022 were granted.

A further concession made to cartels is the adjustment of penalties when it’s decided firms can’t pay the financial penalty that would otherwise apply. While not unique to cartels, four of ten recent anti-competitive cases had penalties reduced when the company claimed it couldn’t pay.

In one case, potential financial penalties ranged between NZ$400,000 and $650,000. In the end this was reduced to $62,500 based on what it was determined the company could pay.

The problem with leniency

The situation raises several questions and issues. First, the messaging is problematic. Offering leniency implies a certain level of acceptance by the community.

As cartel activity is often described as the most serious form of anti-competitive conduct, it’s difficult to reconcile this with an absence of sanctions for those who admit participating in it.

Secondly, there’s the question of equality of treatment in our justice system. Is it fair that only certain (white-collar) offenders enjoy leniency provisions? Anyone participating in cartel conduct can apply for immunity or leniency. This is not the case for those engaged in other criminal activity.

Third, is justice served when a firm can retain the benefits from the historic cartel activity and incur no formal sanction? This can mean the party that engages in the most serious misconduct, such as instigating the cartel, can avoid sanction. Meanwhile, less culpable participants are punished.

Fourth, there’s the problem of reducing or removing financial penalties. We acknowledge the Sentencing Act requires the court to consider the ability of an offender to pay. But we also suggest a market outcome is achieved if a financial sanction results in an offending firm ceasing to trade.

Finally, while it can be argued that leniency provisions help detect cartels, it can also be argued that an absence of leniency provisions deters cartel activity due to the potential for sanctions.

What appears to be a focus on detection rather than deterrence is inconsistent with the approach taken with most other criminal activity. There may well be responses to these questions and issues that prove satisfactory to the community. But they are not obvious.

We need a public debate about why certain types of white-collar criminals have a standing offer of immunity or leniency for confessing to their bad behaviour and divulging the details of others who may be complicit. Justice is challenged when people engaging in the same activity receive different sanctions, and any pretence of getting tough on cartel crime is undermined.![]()

*Lisa Marriott, Professor of Taxation, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington and Edward Willis, Associate professor, University of Otago. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

14 Comments

Would you prefer to be the victim of a violent crime, or financial crime? The general public care more about feeling safe in their homes and communities, than they do about some things costing more money. It doesn’t have the same political power as preventing violent crime, and most of us are sick of seeing the lenient sentences or non-sentences handed out to violent offenders.

Why should those at the bottom respect laws if those further up don't?

I'm sick of seeing lenient treatment for both violent crime and financial crime (incl labour law violations, tax evasion etc.).

You think harsh penalties apply to violent crime in Aotearoa? Most of us would say sentences are often an insult to victims and no real punishment for offenders.

Given many (most?) peoples horror at the pathetic sentences handed down for often horrific violent offenses, I feel these two academics' research on white collar crime is a bit of a waste of effort.

Certainly anti competitive behaviour is something which must be discouraged even to the point of criminal sanction in extreme cases. However, it needs to realised that both the Commerce Commision and the FMA exert day to day surveillance to a point far beyond what private citizens would tolerate if say the police popped in to run the ruler over one's private activities.

I can certainly agree that monopoly power needs careful and effective oversight, and one might observe this applies to both public and commercial monopolies. (I would advance the point that many government fees amount to almost extortion)

But in general, competition, public choice, and, as the authors note, internal whistle blowing act to a reasonable degree as policing of bad commercial behaviour.

If you are rich you can beat a kid with a bed post and get moved to another expensive school. If you are poor you get expelled and end up on the scrap heap. If you are rich you can admit to using class A drugs (Prince Harry) and get away with it. If you are poor, you are jailed or deported. The law in most countries is there to protect the state not the individual. If you are part of the establishment you can get away with anything.

Seeing the victims of fraud in my many years as an accountant showed me that white collar crime has a huge cost. Of course, white collar criminals have access to quality lawyers. And the enforcers are low skilled, overworked, poorly resouced. We let these criminals off, and they continue to have no stain of criminal prosecution against their name. I could mistakenly call it racist. But in reality, it is just privilege. Repellent privilege.

They don't get let off. They get found not guilty. As you say, probably due to your reasons as given. But the poor violent people, in spite of being found guilty, are given very similar sentences to the white collar not guilty defendants. Why would this be?

Try using facts instead of repeating your bigotry.

Yeah...we let them steal huge amounts from workers and hardly lift a finger as the company is transferred into their spouse's name and they carry on with just a small extra cost of doing business.

Financial crime, modern slavery etc have huge costs to society but the "tough on crime" rhetoric never seems to extend to these criminals. But enabling so much financial crime also contributes to the conditions that grow higher volumes of violent crime - i.e. family and community breakdown from financial hardship.

Disgusting also our open toleration of tax evasion in the property sector over these last decades, especially given our problems now with undermaintained infrastructure and inability to get and retain adequate healthcare and other important workers. Moral rot.

I believe in the broken windows approach. Which means every crime is regarded as important, both in prevention, investigation, response and penalty.

Don't care if it is a cartel or a load of kids in a stolen car. Handcuffs for a start. No name suppression.

Those kids in the car are often repeat offenders. So are the commercial fraudsters, big and small. So behind a fence until it's clear there is no possibility of repeat. Thus bail is rare.

Plenty of stories of theft in an office, and then the same thief in another office. Glengary Wines in Mount Eden was ramraided two nights in a row. Police got the offenders both times. And get this - was the same kids.

To paraphrase a Canadian auditor friend: "it's not that New Zealand is necessarily less corrupt than other places, it's just that Kiwis are spectacularly crap at noticing it"

We run on cosy arrangements.

We do not punish ram raiders, petty criminals, gang members, why do you want to single out poor white collar criminals... seems racist

Perhaps the authors should have spelt out WHY leniency was given rather than making sweeping conclusions based on that leniency. There could have been a multitude of reasons and factors for leniency which would make their argument half baked at best. Typical of half baked academics who have never had to do business in the real world, making conclusions based on statistics only.

The main reason for leniency is privilege.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.