By Chris Trotter*

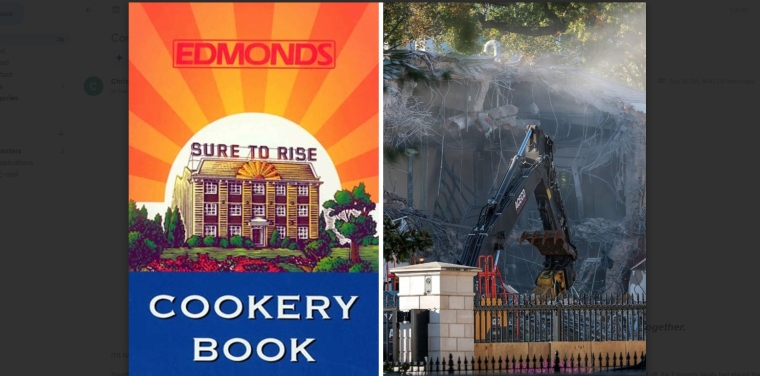

Its image graced a national bestseller. Indeed, the Edmonds family’s Christchurch factory could lay credible claim to being one of New Zealand’s most iconic buildings.

Standing amidst lovingly maintained gardens in the midst of Woolston’s industrial sprawl, the factory’s façade was an architectural oddity – as if a cottage had taken too many steroids. To top it off, the Edmonds family had placed their company’s slogan on the façade’s roof in letters three metres high.

“Sure to rise” was a reference to the company’s baking powder but, over time, New Zealanders would invest it with meanings of their own.

How does a building become iconic? Truthfully, the answer has very little to do with architecture. A building becomes iconic by virtue of being seen. It was the family’s decision to put the façade of its Woolston factory on the cover of the Edmonds Cookery Book – a publication whose 4 million sales meant that it could be found in just about every New Zealand kitchen – that transformed the building into a national icon.

It is, therefore, entirely understandable that when the building was demolished New Zealanders were crushed. No amount of submitting, or protesting, or last-minute appeals, made the slightest difference.

Edmonds had fallen victim to the quintessential corporate raider, Ron Brierly, in the 1980s. The century-old family company was very far from being the first to be asset-stripped and reduced to rubble, but the unique place it occupied in the national imagination meant that its destruction could not avoid making headlines.

Also unavoidable was the way in which the building (bowled-over and its gardens bulldozed flat in a matter of hours as local residents scrambled to rescue what they could of its contents) came to symbolise the way pre-1984 New Zealand had been flattened to make way for Roger Douglas’s free-market future. When those three-metre-high letters came crashing to the ground in 1990, everybody understood that “old” New Zealand would not rise again.

What stirred these thirty-five-year-old memories? It was the ruthless destruction of another iconic building – the East-wing of the White House in Washington DC. Somehow, heavy demolition equipment had made its way onto President’s Park – a supposedly federally-controlled National Park – and in a matter of hours reduced this 1942 addition to the White House complex to a pile of rubble.

Now, bowling-over an edifice that had stood beside the Executive Residence for a mere 83 years may not seem all that important. After all, the White House (so called for the white coat of paint applied to mask the extensive charring caused by British soldiers during the War of 1812, is an impressive 233 years old.

But that, surely, is the point. Every president since George Washington’s immediate successor, John Adams, has occupied the Executive Residence for the duration of his presidency. It has become an integral aspect of the office of president – alongside the Oath of Office and the Inaugural Address. So much so that the words themselves, “the White House”, have achieved synecdochical status. When a journalist declares “the White House said today”, they are referencing the president and his staff.

Prior to the present incumbent, no American president has remodelled and/or added to the Executive Residence and its attached edifices without first securing the active participation and explicit consent of Congress. The White House belongs to the American republic and its citizens, meaning the presidents who inhabit the residence do so ex officio – by virtue of their office – they do not own it, and they cannot, or, at least, they should not, change it without first consulting both the government and the people of the United States.

What, then, does it mean that the East Wing of the White House has been demolished in the absence of formal public consultation, and without congressional approval?

The actions of the 45th President, Donald J. Trump, can be construed in only one way. That he believes himself to be the effectual owner of the Executive Residence, and that he is, by virtue of that ownership, perfectly entitled to knock down anything he goddamn pleases. Trump does not believe himself to be a tenant of the American people, but the sole executor of their estate.

As legal cover for this latest – and all the other – assertions of Executive Authority, Trump will doubtless refer his critics to Article Two of the US Constitution. This is the article setting forth the powers and responsibilities of the President of the United States. It’s first sentence is unequivocal:

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”

Proving that “executive Power” does not encompass knocking down parts of the Executive Residence might prove unexpectedly difficult. That all previous administrations have interpreted those words in the light of the customs and practices of their predecessors, and according to the general expectations of the American voter, in no way binds the incumbent to do likewise.

Executive power may yet turn out to mean: wanting to knock down the East Wing of the White House, and having the authority to do exactly that.

If that is what the Supreme Court of the United States affirms the first sentence of Article Two to mean, then in every circumstance what the President of the United States wants, the government of the United States is bound to give him. To “execute” is, after all, to “put into effect”. Historically, the Supreme Court has taken that to mean putting into effect the laws, regulations, and declarations of Congress. But today’s Supremes may yet choose to make history, rather than follow it.

The ballroom Trump intends to erect on the site of the now demolished East Wing will be huge. Judging by the preliminary drawings that Trump’s staff have made available, the structure will dwarf the rest of the White House complex. Indeed, it will rival the ballrooms of Versailles, and glitter with even more gold. According to the President, this gargantuan edifice will be funded by America’s tech billionaires and, when completed, will accommodate 999 guests.

During his in/famous “Checkers” speech of 1952, Richard Nixon, then Dwight Eisenhower’s running-mate, told the American people that his wife “Pat doesn’t have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat”.

Those words were not just the words of a Republican vice-presidential candidate, they were also, and more importantly, the words of a republican.

Vast edifices, paid for by fabulously wealthy aristocrats, to secure the favour of the man who ordered their construction – on the not unreasonable grounds that if he has the power to build things, then he must also have the power to much, much more – have historically been the special preserve of kings and emperors, not democratically-elected and democratically-accountable presidents.

No less than the ruins of the Edmonds factory, the ruins of the East Wing of the White House are symbolic of the passing of an old order, and the arrival of a new one. But if Trump’s imperial ballroom is sure to rise, then equally the American republic and American democracy, as the world has come to know them, are sure to fall.

*Chris Trotter has been writing and commenting professionally about New Zealand politics for more than 30 years. He writes a weekly column for interest.co.nz. His work may also be found at http://bowalleyroad.blogspot.com.

13 Comments

I quite approve of those aristocrats who paid for York Minster, Durham and Ely cathedrals. They left impressive edifices built when the average home was a mud hut. They are a reason for visiting the country of my birth. However there is little in the UK built by their democratically elected govts that are worth visiting.

What edifices does NZ possess that encourages the return of Kiwis on holiday?

At some point people realised we could take the resources and labour needed to build one cathedral and use it instead to convert 10,000 mud huts into solid brick homes. Not hard to understand why the latter will always be more popular in a democracy.

At some point people realised we could take the resources and labour needed to build one cathedral and use it instead to convert 10,000 mud huts into solid brick homes. Not hard to understand why the latter will always be more popular in a democracy.

All respects to your clarity of thought sir / madam / them_they.

Natural ones?

Probably wouldn't have survived the earthquake anyway as Woolston was hit particularly badly. Pulling it down early might have even saved some lives.

And Presidents on both sides have long bemoaned the lack of conference facilities at a place that hosts a lot of conferences and has needed to semi-permanently install marquees, which are less than adequate for a number of reasons including security. And remember this guy nearly had his ear blown off recently and has dodged a few other bullets.

Sometimes it's ok to be practical. Not everything has to have an ideological moral.

Sheesh.

This isn't about being practical - this is about grandiosity.

And the bigger worry is that half the (greatest the world will ever see, but visibly decaying) hegemony voted for it.

Twice.

The greatest buildings have been built with a singularity of vision that democracies typically don't allow, so maybe tying institutions to builds isn't such a good idea as it ties us to a past and, when it's in the government sphere, with a focus on not offending anyone and concomitant lack of vision.

It's why there are several Guggenheim museums that include some of the most iconic buildings of the 20th and 21st centuries: they were funded by private money with a singular vision and architects turned loose by their clients. And these are publicly accessible spaces, not personal palaces.

In contrast we get Te Papa, which is a piece of beige committee design that doesn't work cohesively as a museum and that no-one cares enough about to protest when an apartment development screened the view of it from the harbour. It was a gigantic missed opportunity.

Notably, the government-managed selection process rejected the Ian Athfield-Frank Ghery proposal for the Museum of New Zealand in the early stages. Frank Ghery went on to deign the Bilbao Guggenheim and the Disney concert hall. Ghery even found something to delight in the use of something as prosaic as bricks.

Most people sort of miss the point of CT article I suggest. The real point is what does "Executive Power" really mean?

Recall that after his first term Trump claimed he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue, and he wouldn't lose any voters. It is clear that is the view he appears to have of the limits of his executive privilege - that there are none, despite laws and legal precedent to the contrary (in some instances). The GOP caucus in the house are essentially backing him on this.

Trump as President has immunity full stop. Thus he can do as he wishes and given his state of self bestowed infallibility, anyone else can simply like it or lump it

"Trump as President has immunity full stop." That is what he wants and what the Republicans in control of the house have essentially given him, But US Law and the constitution says otherwise. The three houses (Senate, Congress and the Executive Office) are supposed to be checks on each other.

He seems to be backing away from seizing power for at least a third term, so whatever he is replaced with will face the problem of how to deal with what he did while in office and his obvious corruption.

Looking at Polymarket, Trump is a 5% chance to win the 2028 election. That suggests comfortably over a 10% chance he will run if he's physically able. There's another 3% from junior Trump family members.

For something that will really scare some around here, AOC is at 9% to win. And amusingly, Buttigieg and Kamala Harris are both just trailing Dwayne Johnson at 3%.

The people of Dunedin are easily influenced by the smart guys.

Thousands of old rotting houses in Dunedin. And a monster stadium.

Give the people circuses. They will fall for it every time.

And soon the good people of Christchurch will be joining the party thus ensuring that ratepayers of both cities are subsidizing the 250 people who turn up to watch rugby each week over the winter.

The vastly unpopular Stadium cost most of the councillors who voted for it their jobs at the next election, but by then all the contracts were signed. The lasting legacy are maintenance and debt servicing financial haemorrhages and a lot of public bitterness that seems to have permanently changed Dunedinite's view of the council.

We really, really need recall legislation and binding referendums for local government to stop them going out of mandate.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.