Early last month, Inland Revenue issued a draft interpretation statement The Commissioner's duty of care and management under Section 6A of the Tax Administration Act 1994. This is a largely unchanged update of the previous interpretation statement issued in 2010.

This might sound a little arcane, but Section 6A, and the related section 6 of the Tax Administration Act are, in my mind, two of the most important sections in the tax legislation. As the interpretation statement puts it, “these are important provisions governing the day-to-day operation of Inland Revenue and the exercise of the Commissioner's power of the under the Inland Revenue Acts.”

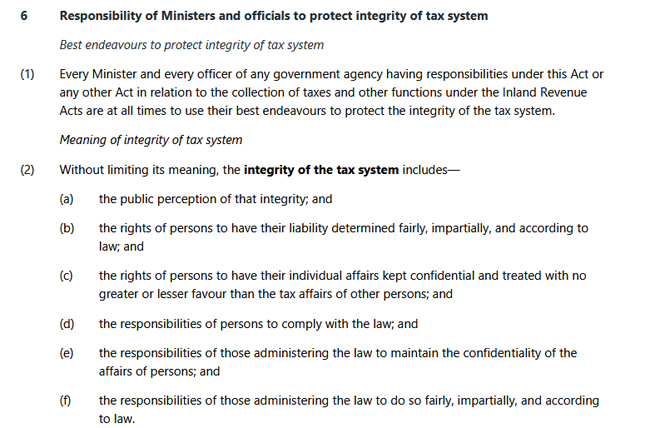

So, what are these provisions? As you can see Section 6 requires Ministers and officials to “protect integrity of tax system” including “the public perception of that integrity.”

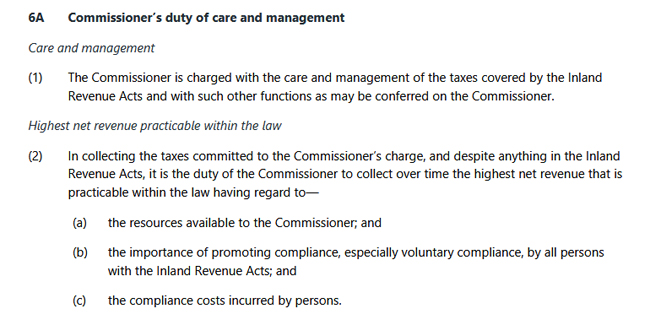

Section 6A then sets out the Commissioner’s duty of care and management.

What does “care and management” mean and why are these provisions here. is it there? The opening two paragraphs of the interpretation statement explains it as follows:

“A reality of modern tax administration is that the Commissioner must operate the tax system with limited resources. This means the Commissioner cannot always collect every last dollar of tax owing in every case. As a result, the Commissioner must decide how to best use his resources to maximise the taxes collected and to foster the integrity and effective functioning of the tax system.

The Commissioner’s resource allocation and management decisions can affect the integrity of the tax system, including taxpayers’ perceptions of that integrity. What one taxpayer may consider as flexibility that achieves a practical and sensible outcome, others may consider as inconsistency or favouritism.”

What has this got to do with Mickey Mouse?

Setting out the history as to how this section gets here is very interesting, and that's where Mickey Mouse comes into play. It might be no surprise to find out the actual origins of Mickey Mouse's involvement in our tax system go back to the UK and a case known as the Fleet St Casuals[i] case.

This was a decision by [the British] HM Inspector of Taxes to reach a settlement with casual workers in the Fleet Street printing industry who had not been compliant with meeting their tax obligations. Instead the workers had “engaged in the process of depriving the Inland Revenue of tax due on their casual earnings.”

As part of this the casual workers had falsified their identities and addresses when collecting their pay so that HM Inspector of Taxes could not assess and collect tax due. Apparently, Mickey Mouse of 1 Sunset Blvd was a regular worker and there were several similar such aliases employed. When the HM Inspector of Taxes investigated, they found there was around 6,000 workers who had not been compliant at all, and many of them had provided false addresses. Chasing down every amount of tax due was impracticable. So, a settlement was reached.

When this became known it attracted the ire of the National Federation of Self-Employed and Small Businesses, and they took a case against the Commissioner of Revenue, on the basis that they were being unfairly discriminated against. The Federation sought out a writ of mandamus to basically compel the Commissioner to assess and collect all taxes properly owed.

The case eventually reached the House of Lords, who held that the Commissioner had a “wide managerial discretion under Section 1 of the Taxes Management Act.” It was therefore within the exercise of the Commissioner’s care and management to reach settlements, even though not all the tax due would be collected.

The Organisational Review of Inland Revenue

Back in 1981, when the House of Lords decided the case, there was no such equivalent provision in New Zealand. During the overhaul of our tax system in the 1980s and early 1990s, the Valabh Committee concluded that a similar measure was needed. Subsequently an organisational review of Inland Revenue was carried out by a committee chaired by Sir Ivor Richardson, the late great tax jurist. This was a highly important review if now somewhat lost in the mists of time.

The Organisational Review’s 1994 report concluded a similar discretion to that of the UK was needed and this led to the introduction of sections 6 and 6A of the Tax Administration Act. (The Organisational Review also prompted a substantial overhaul of the dispute process which is another story).

The thrust of Section 6 and 6A is Inland Revenue has some discretion about how far it can use its resources to collect tax, but in doing so it is bound by keeping the perceptions of the integrity of the tax system. A key point that is repeatedly made clear is that discretionary care and management does not mean that Inland Revenue can override or ignore tax law that exists. Nor do sections 6 and 6A give the Commissioner of Inland Revenue the ability to issue what might be called extra statutory concessions.

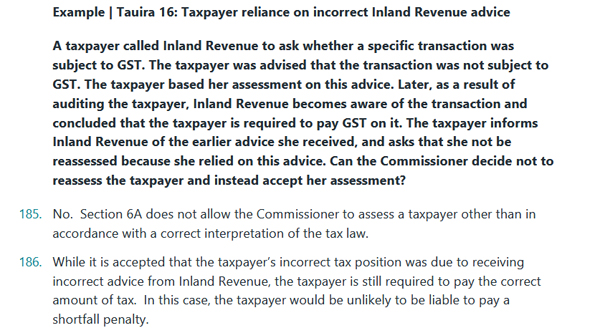

The interpretation statement includes a useful appendix setting out the history of the provisions. There's a separate handy reading guide accompanying it as well for those who want to avoid wading through the full 59-page consultation. As is now common, the interpretation statement contains 17 examples illustrating how the Commissioner might use his discretion. This example will sound familiar.

The response given in the above example is what I would expect to see. Although it addresses the issue of a shortfall penalty, what about use of money interest? Would the Commissioner have discretion to remit that interest? The example doesn't cover that, but it's something that a taxpayer might raise an objection about. Obviously, everything is fact dependent and Inland Revenue may be able to point out that key facts were not provided at the time of the initial inquiry.

As I said, this is a highly important document. Even though the practical effects on day-to-day taxpayers may not seem significant, it's good to see it updated.

What about Inland Revenue mistakes?

On the other hand, I have to say that the emphasis on Section 6A does overlook the question of whether operational practices of Inland Revenue may be a breach of Section 6. In other words, Inland Revenue does something operationally, which may be correct under the law, but actually is highly disruptive to taxpayers because it failed to process matters promptly or incorrectly.

What happens then, and also regarding the matter of costs that are incurred by the taxpayer? How does that affect the integrity of the tax system or taxpayers’ perception of the integrity tax system?

This is an interesting area and one where I think we ought to see more case law involved. But as this updated paper points out, there's only been four tax cases since 2010 where there has been some reference to section 6A so it is yet to be tested. Consultation is open until 26th May

Inland Revenue’s clampdown on the property industry

Speaking of Inland Revenue and reassessments, last week Inland Revenue released a press release proclaiming its latest success in the clamp down on under-declared income and GST.

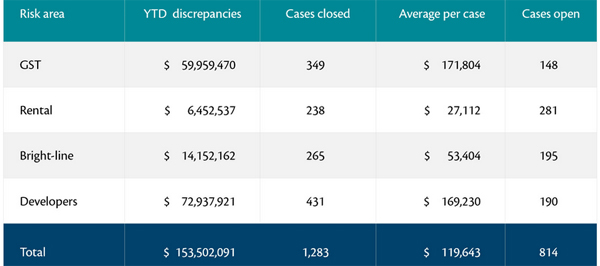

According to the press release, it has uncovered more than $150 million in undeclared income tax and GST from the property sector. This initiative is part of the additional $116 million funding given to Inland Revenue in last year's budget. According to the press release, the $153.5 million discrepancy for the first nine months of the current financial year is almost the same as the total $156.8 million figure for the whole of the year ended 30th June 2024.

Now, there are four risk areas identified here. GST, rental, bright line and developers. The majority of the discrepancies relate to GST and developers.

Defaulting developers under increased scrutiny

The press release also revealed Inland Revenue is focusing on defaulting developers because

“…we're also seeing a pattern of property developers claiming significant refunds as they incur costs upfront but then failing to file and pay once properties sell.

Where we expect a GST payment from a property sale and we don’t see the sale in the return, we contact the developer to make enquiries.

If there is no response or no return filed, we will take enforcement action quickly.”

This is unsurprising and will be an ongoing project. As noted above, Inland Revenue got $116 million over four years in last year's budget. I would expect it to get more in this year's budget, but who knows at this point?

Five proposals to improve the tax system

Last month I had the very great privilege of speaking to Inland Revenue’s Policy Advice Division. They asked me to present to them some of my insights about the tax system and on communicating tax policy. It was a fascinating session around those wide-ranging topics. The Q and A session was particularly interesting and entertaining. Again, my thanks to Inland Revenue for inviting me along. It was an enormous privilege to speak to you all. I thoroughly enjoyed it, and I hope you did too.

Now, one of the questions was “if you're in charge of tax policy for a day, what changes would you propose?”. I put forward the following five proposals.

Number one – introduce a capital gains tax

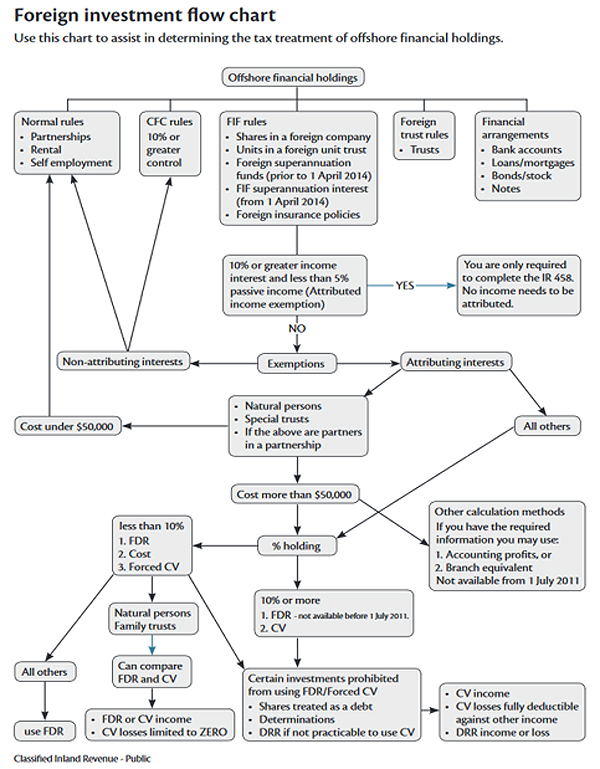

Firstly, I would introduce a capital gains tax, and I would do so as much for economic efficiency and clarity as for raising revenue. I don't accept the argument that it's too complex. Anyone who looks at the Foreign Investment Fund and financial arrangement regimes, both of which trip up experienced taxpayers and practitioners, can't honestly be saying a CGT would be too complex.

At present there's a large part of our tax system, particularly in relation to property transactions, that contains some rather subjective definitions around a person’s intent or work of a minor nature. Those are subjective terms and perhaps unsurprisingly, in my experience non-tax specialists people tend to think tax should be pretty much cut and dried. It is therefore surprising for them to discover there is so much potential subjectivity involved.

But I also think that when you consider how our economy has developed over the last 40 years leading to over investment in property (in my opinion and that of economists such as Bernard Hickey and Associate Professor Susan St John), then trying to shift the allocation of capital away from investing in property would be a good thing. I'm not saying capital gains tax would solve that issue overnight, but it would be a start.

Second - time for the “Fair Economic Return”

My second suggestion would be the fair economic return (FER), which is something that I've talked about before which I’ve developed alongside Susan St John. How it operates is that above a certain threshold, a set percentage will be applied to the net value of a person’s residential property. I see this alongside a capital gains tax as a twin track approach to address the issue of better allocation of capital.

Furthermore, as the Tax Working Group noted in its discussion of the deemed return method (on which FER is based), it would initially raise more revenue than a CGT, and we need to raise revenue. The Government's books are clearly under strain, and this will increase. That was something I talked to Inland Revenue Policy about where I saw the strains manifesting. Cost cutting is part of managing the books, but in my view, tax increases are inevitable.

Third, mandatory indexation of income tax thresholds

The suggestion I have, and this has been a bugbear of mine for quite some time, is automatic indexation of income tax thresholds. To me, this is primarily about transparency and addressing the issue of fiscal drag (when inflation pushes taxpayers into higher tax brackets).

Fiscal drag has been a tool which governments of both hues over the past 30 years have been very happy to use to disguise the actual tax take. It led to the position we saw last year, where in the first threshold adjustment since 2010, the adjustment was limited to inflation since 2017. In other words, a lot of inflation gains were locked in.

I think there's a lack of transparency about this process and it doesn't just extend to income tax thresholds. It also extends to other income tax thresholds, in particular around the financial arrangements regime which have not been adjusted since 1999. It doesn't apply to GST, however, because I think there are different issues involved with the GST threshold.

These thresholds wouldn't need to be changed annually as happens in the United States, but they could be changed no more than three yearly or when a threshold, say 5% inflation, has been breached. The key thing is these threshold changes would happen automatically unless the government of the day specifically legislated otherwise. If a government decides not to increase thresholds this decision goes through the regular Parliamentary legislative process and the government must then explain its decision.

Legalise and tax cannabis

I don't smoke, but around the world there has been a trend to legalising/decriminalising cannabis. The present criminal status of marijuana enables its supply to be captured by organised crime syndicates and those of you who know crime history will know that it was tax evasion that got Al Capone busted.

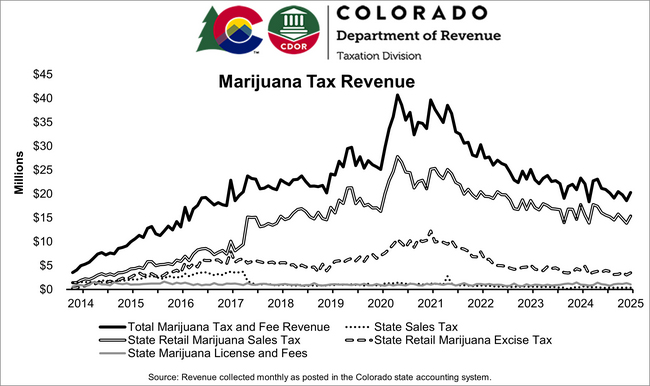

I think legalisation of cannabis is something that should happen and could be a useful revenue raiser. To give an example, Colorado, a state of about five million people, legalised cannabis in February 2014 and since then, its total tax collected has been over US$2.9 billion, roughly NZ$5 billion. In the year to December 2024, it collected US$255 million, about NZ$440 million.

Granted, the tax take from marijuana in has been falling in recent years. But that's because other states are legalising it as well. If I was Nicola Willis, I'm not sure I'd want to leave a potential $400 million plus per year lying around.

Finally, time for a Tax Ombudsman

Finally, I would establish a tax ombudsman and a tax advocate for small businesses and small taxpayers. This is a more administrative issue, but it's based on a report I was lucky enough to prepare for the Tax Working Group in 2018.

A tax ombudsman is common in other jurisdictions. For example, when preparing my report for the Tax Working Group, I spoke to the then Inspector-General of Taxation and Tax Ombudsman of Australia. It could be a standalone office, or it could be part of the Ombudsman's office. Either way, it would give taxpayers a second right of complaint against improper practises as they see it, by Inland Revenue. In that way it ties into our main story this week about Inland Revenue’s duty to preserve the integrity of the tax system.

The tax advocate together with changes to the dispute process would redress the imbalance between Inland Revenue and smaller taxpayers. Something I raised in my presentation to Inland Revenue, is that for a very litigious subject, we actually don't have many tax cases going through the courts (something Supreme Court Justice Glazebrook has also noted). I consider in many cases Inland Revenue wins because it is playing with a loaded deck. This is the result of the changes following the Organisational Review Committee. I think 30 years on from that review its time we had another look.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā.

[i] Inland Revenue Commissioners v National Federation of Self-Employed and Small Businesses Ltd [1981] 2 All ER 93

11 Comments

Always a pleasure to read Terry's comments. On his proposals:

1. CGT - not necessarily opposed but has anyone done any studies about whether CGT on residential real estate would be inflationary?

2. FER - not so keen as it is harder to understand, than say CGT, but fully agree that we need to raise more revenue. Not sure the numbers, but if FER would raise more revenue that CGT, one could just up the rate of CGT due on sale, perhaps.

3. Auto indexation of tax thresholds - an absolute no brainer. I like the idea of it being triggered when inflation reaches a certain percentage, but imagine what would happen if we had rampant inflation. So perhaps a timeframe might be 'safer'.

4. Legalise cannabis - for sure. I can't believe that commodity didn't get the nod during the referendum. Stupid leaving that potential tax behind AND at the same time largely leaving distribution with organised crime.

5. Tax Commissioner - I'd prefer a standalone officer of Parliament who would also manage the advocacy program. I have always felt the advocacy aspect of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment office, should provide advocacy/advice for individuals/members of the public trying to navigate the planning system.

I always enjoy your reasoned comments, Kate. So, my question is "Why not a simple land tax, rather than CGT?" Easy to administer, hard to avoid.

Would like to know your thoughts.

Thank you! I do very much favour land taxes - but as part of a whole re-design of our tax system, as opposed to an 'additional element' as in the context of Terry's 5 recommendations.

So, land taxes to offset, for example, labour (income) and company taxes.

The attractiveness about CGT is that it is always 'affordable', as one has already 'raised' it as a result of the sale of an asset (if one doesn't want to incur the tax liability; one can choose not to sell the asset) -

Whereas land taxes, like rates, are unavoidable as you say. One could exempt the family home (as has been proposed by some - and I think one of the Tax Working Groups did that), but then it becomes less efficient and much less a broad tax - such as income tax is.

In general, I'd rather society taxed capital and consumption, as opposed to labour and profit.

Isn't a land value tax on unrealised value very hard on those with an asset but little cash-flow?

To descend in to the particular: I'm thinking people who have a family home that's accidentally become worth a lot (I'm thinking of things like the old places in Grafton and other inner-city areas that were cheap buying in the 1970s or 80s, but now are worth astronomical sums), but are still trying to make ends meet on a pension and can do so only becasue they managed to retire their debt. I think the vision a lot of people have is of being forced to take out reverse mortgages to pay tax bills - which enriches only the banks - while they gradually lose what may have been a multi-generational home.

Their rates will be high if the place is worth a lot so they'd have the same situation regardless though right? Is it not the same argument if a pensioner is low on funding and can't afford rates, they already get rates discounts, and if they can't afford it they have to make life decisions: Sell other assets, downsize and sell up, reverse mortgage, etc.

FER - as a tax it's less efficient than LVT and whilst I think it's conceptually fair, I think that is a challenging claim to sell with the general public. What's more, the exemption threshold is unfair and means the tax entrenches advantages of single home owners over renters. It seems that many reform advocates are obsessed with bringing down multiple home owners rather than closing the gap for those with no assets at all - probably because they and their friends don't fall into that later group.

Anyway, in practice I think the politically viable way to shift tax burden off productive work and onto assets is something like a simple no exemptions LVT linked to government infrastructure spend and administered as part of council rates. Manifestly fair and efficient both economically and administratively.

Terry, I'd be curious to hear any arguments for why you favour FER / CGT over an LVT. It's certainly possible that I'm missing something in my assessment!

FER is blatant envy theft of private property. Conceptually identical to TOPs socialist policies of stealing from people who worked all their lives to provide a home for themselves and their families to handout to people who can't be bothered getting out of bed..

The reasoning is that in the long term most government investment flows to property owners, either directly via them enjoying the benefits of the infrastructure, or indirectly via being able to charge more rent to their tenants. That's not socialist envy, it's well established economic theory going back centuries and widely accepted by economists on both the right and the left. It's therefore totally fair that government investment should be funded by the property owners that it benefits, not by workers who don't get to enjoy the benefits of that infrastructure (or at least have to pay commensurately higher rent for the privilege of doing so).

I get that there could be complaints about "changing the rules of the game halfway through" because it means some people getting hit twice, but that aside I don't really see much of a case for income tax being fairer than FER. It is particularly bizarre that you complain about supporting those who don't work whilst backing the status quo which specifically targets those who bother to work for taxation.

The Green Party says...hold my beer

https://www.stuff.co.nz/politics/360688012/green-budget-would-see-88-bi…

I wonder if the Greens would be quite prepared for the consequences of implementing those policies.

For a start: capital and enterprise flight, higher borrowing rates for the country as a whole, the costs of administering things like asset registers, and justifying why things like wealth taxes are desired when they've been abandoned in other places becasue they don't work that well.

There are many people who view CGT as a revenue gathering exercise only. We already have CGT in some areas but not in others. Furthermore one has to be very careful on realised and unrealised gains. We already have unrealised CGT on some assets. There should be no unrealised gains of any form. The main reason I'd suggest for a limited CGT is to make an effort to level the investment playing field. Revenue gathering is a consequence of that.

No FER until there is drastic RMA, Building Act and regs and local council reg changes as to what you can do on your property. Definitely none on your primary residence where you live.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.