Late last week, Inland Revenue released its draft long-term insights briefing (LTIB) Stable bases and flexible rates New Zealand’s tax system for consultation. As discussed in previous podcasts, these long-term insight briefings are required to be prepared every three years by government agencies.

As Inland Revenue explains these briefings provide information on long-term trends, risks and opportunities as well as possible policy responses.

Importantly the briefings are developed by departments independently of ministers and are not current government policy. Briefings discuss the pros and cons of various options responding to these trends and consequently promote public debate.

Long-term fiscal pressures ahead

We’ll see quite a few of these, Treasury has one due which will be highly important as it will almost certainly tie into the themes of this Inland Revenue because as the LTIB’s executive summary explains

“The key motivation for this LTIB is that New Zealand, like other developed countries, faces long-term fiscal pressures. In particular the ageing of the population will place upward pressure on superannuation and healthcare expenditure over time…the fiscal system will be more resilient if the tax system can easily adapt to changing revenue needs over time.”

Against this background, the key question explored in the LTIB is how to design “a durable tax system” to cope with these pressures. According to Inland Revenue

“…a durable tax system is one with a stable core structure while providing the flexibility to adapt to changing revenue needs or the different distributional objectives of different governments over time. Given this key question, the focus in this LTIB is on taxes aimed at raising revenue.”

Given the current Government’s ideology raising this matter puts the cat amongst the pigeons.

The LTIB runs to 132 pages, including seven pages of references. There are also a couple of interesting Analytical notes, one on the tax treatment of risk and lock-in, and the second an overview of the data and methodology used to create the land data considered in Chapter 6 of the LTIB.

There’s an enormous amount to consider because basically this LTIB is similar to the briefs given to the three tax working groups this century. All started on the basis of what revenue is needed, what represents a stable tax system and what are the risks, opportunities, etc.

Given the scope of the LTIB I’m not going to discuss the LTIB today in any detail. Instead, I will bring you a separate podcast episode with a couple of guests bringing different perspectives to discuss the key issues.

Climate change adding to the fiscal pressures?

Since the Cullen Tax Working Group report in 2019 there’s increasing emphasis on the fiscal pressures ahead, with the main discussion around rising superannuation and health costs. My personal view is the costs of our changing environment will be the crunch point forcing changes to the tax system.

We are experiencing major flooding very regularly now with the Nelson Tasman Region hit very hard this past week. Taranaki also copped heavy rainfall and tornadoes on Thursday and Friday. (Ironically, this is after the Government in March declared a medium-scale adverse event for the Taranaki region because of hot, dry conditions and below average rainfall).

We're now into winter so we may see more bad weather events. These events are putting pressure on local councils to maintain stop banks and other flood defences. Councils are under strain with many having inadequate rating bases to maintain the infrastructure necessary.

Consequently I think a whole rethink of our approach to local government financing and the need for central government support to manage the risk is going to become more and more paramount within this decade.

GST changes?

There's obviously much to digest but helpfully, there is an 11-page summary, which I would recommend to anyone who's interested in tax read as a starting point. Away from the main theme there are quite a number of interesting issues raised in the LTIB. I spoke to Newsroom about the intriguing discussion around potential alternatives for GST and for making it less regressive for low-income earners.

An important briefing in uncertain times

In my view this is one of the most important briefings Inland Revenue have done in a while. I would expect it to generate quite a lot of interest and submissions. It should also be considered as a companion to Treasury’s forthcoming long-term insights briefing on the forward fiscal position.

I think both briefings will point to the need to cut our coat according to our cloth. This may mean tax increases, but there will also be hard decisions around superannuation, for example.

There are other funding strains including an international situation which is not looking terribly great. NATO has just announced it's increasing defence spending to 5% of GDP, which is well into Cold War era levels. This commitment puts pressure on our government, as it would require a near tripling of the defence budget to match NATO.

Submissions are open until 1st September and once Inland Revenue has received and considered submissions it will then finalise and present the briefing to Parliament. The LTIB asks submitters to consider the following nine questions:

Get to it! And stay tuned for our special episode coming soon.

Has the G7 just killed the global minimum tax?

Speaking of international developments, the G7 met last month but its meeting was largely overshadowed by the Iran-Israel War and President Trump's need to attend to that. However, what eventually came out of the meeting is a development which, in my view, spells the end of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (the OECD) international tax agreement known as the Two Pillar solution.

This initiative has generated ferocious pushback from American multinationals and the tech companies in particular, who really seem to have captured President Trump's ear. They felt this was directed mainly at American multinationals. As the biggest boys on the block that’s hardly surprising.

Although much heralded it had become increasingly obvious to me, at least, that the Two-Pillar Solution was under enormous political pressure and it really could only work if the Americans signed up to it. However, once President Trump was re-elected, he made it clear any countries levying taxes deemed unfavourable to the United States could be the subject of retaliatory tariffs.

What the G7 have now come up with is described as a compromise on the Pillar Two global minimum tax rate of 15%. It basically says that American multinationals will not be subject to the Pillar Two proposals. Instead they will be subject to what’s described as “a side-by-side system.”

There's an interesting post on this development by Pascal Saint-Amans for Bruegal, a European think-tank. Saint-Amans was the director of the Centre for Tax Policy Administration at the OECD from 2012 until 2022.

He played a key part in the role in the advancement of what we now call the Common Reporting Standards of tax transparency, and he was also involved in the early stages of the Two-Pillar Solution. It's therefore very interesting to see his take on the news.

He notes that the removal of the global minimum tax for US companies means there are issues around competitiveness as a result. But he also discusses the American Global Intangible Low Tax Income regime (GILTI) which is a quasi-minimum global tax. GILTI applies to US companies who have undertaxed profits declared abroad with an average effective tax rate below 10.5%. (That differs from what was going to Pillar Two which is 15% and was calculated on a country-by-country basis).

The US has basically carved out exemption for itself, but apparently also included in the huge One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which has just been passed by Congress there are measures relating to the GILTI regime which lifts the average tax rate to 14%.

What next?

Although the US Treasury announcement says the “side-by-side system would include a commitment to ensure any substantial risks that may be identified with respect to the level playing field, or risks of base erosion and profit shifting, are addressed”, the G7 move probably derails the Pillar Two process.

One of the reasons it wasn't popular with the multinationals was because it was highly compliance intensive. Whether it would have raised the level of tax people expected, up to US$200 billion annually, we will never know.

I think the announcement will open the door to tax agencies around the world putting increased pressure on the transfer pricing activities of multinationals and the large US multinationals in particular. We could see more cases similar to the Australian PepsiCo case involving deemed royalties I’ve previously discussed.

The G7 announcement is definitely a big setback for the push towards a global minimum tax but I also think it's another shot in the long running battle between tax authorities and tax planners.

Student loan scheme

Last Thursday I spoke to Checkpoint’s Lisa Owen on Radio New Zealand about Inland Revenue’s management of the student loan scheme.

RNZ was reporting on the pressure that many overseas borrowers felt about their debts and Inland Revenue’s approach which includes threatening those who are non-compliant with potential arrest at the border once it has obtained a District Court order. Since 1 July last year, 89 defaulters have been warned that they could be subject to arrest when they come back.

I've been looking at this issue for some time now and Inland Revenue’s handling does seem to be increasingly heavy-handed. That said it is partly constrained in some areas, such as writing off interest for example because of the way the scheme was designed.

Nearly 80,000 overseas borrowers are in default

Inland Revenue has improved its debt collection from overseas based borrowers with a 43% increase in repayments since July last year compared to the same period in the previous year.

However, According to Inland Revenue as of 30 April, there are 113,733 overseas borrowers, 71% of which of whom are in default owing $2.3 billion, including over a billion dollars in interest and penalties.

Included in this group are 24,000 who have debt which is more than 15 years old and who apparently aren't registered with myIR and don't have a repayment plan in place. (It’s actually quite difficult to register for myIR in some circumstances if you're overseas). Apparently, this group owes $1.3 billion, including penalties and interest of $696 million.

What is the purpose of the Student Loan scheme?

I think there's a whole heap of things around the scheme that need to be reconsidered. First of all, what are we trying to do here with the student loan scheme?

Set up in 1991, and deeply unpopular at the time, it is now over 30 years old. That’s long enough for us to revisit the objectives behind the scheme, and how are they being achieved?

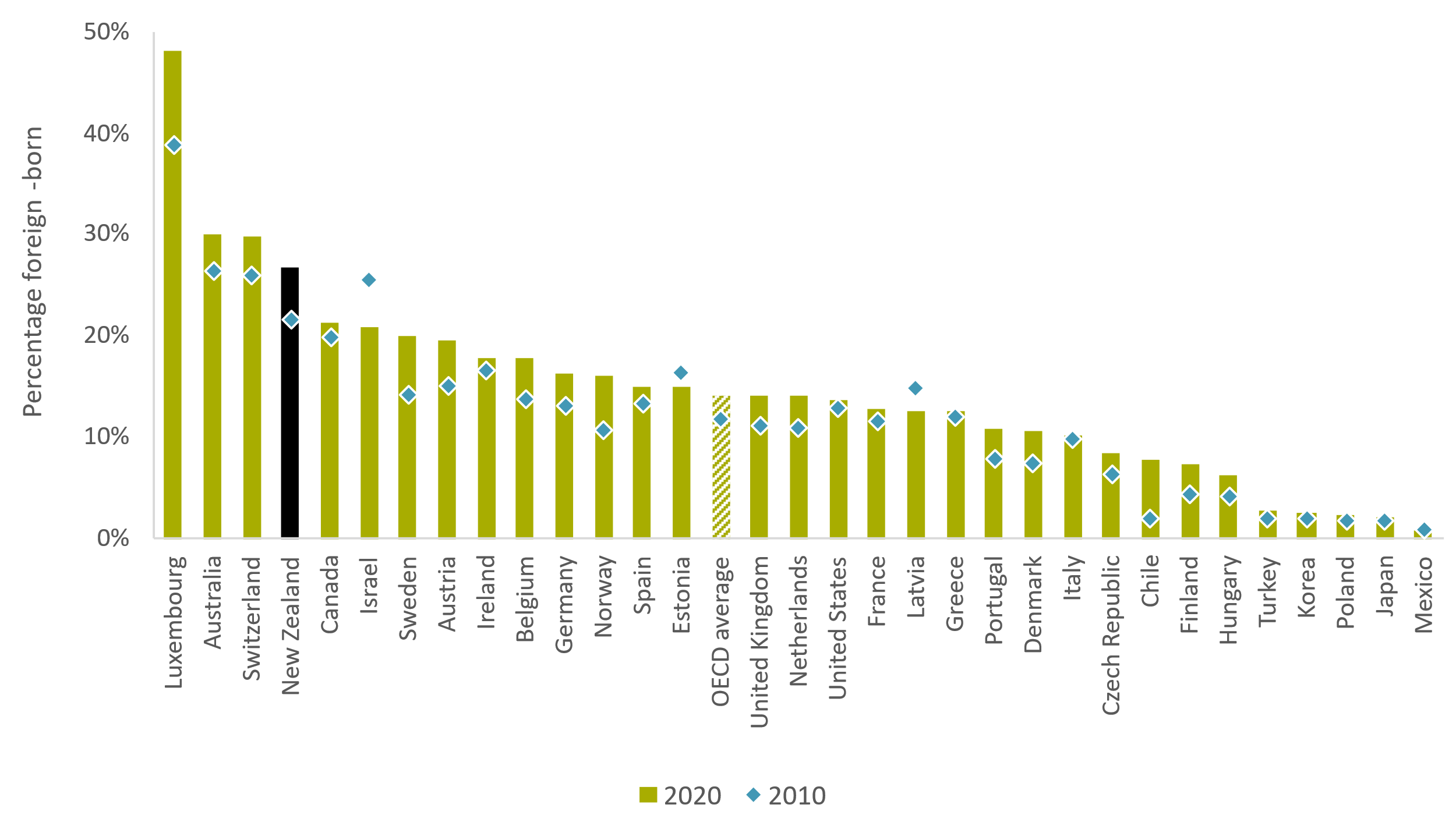

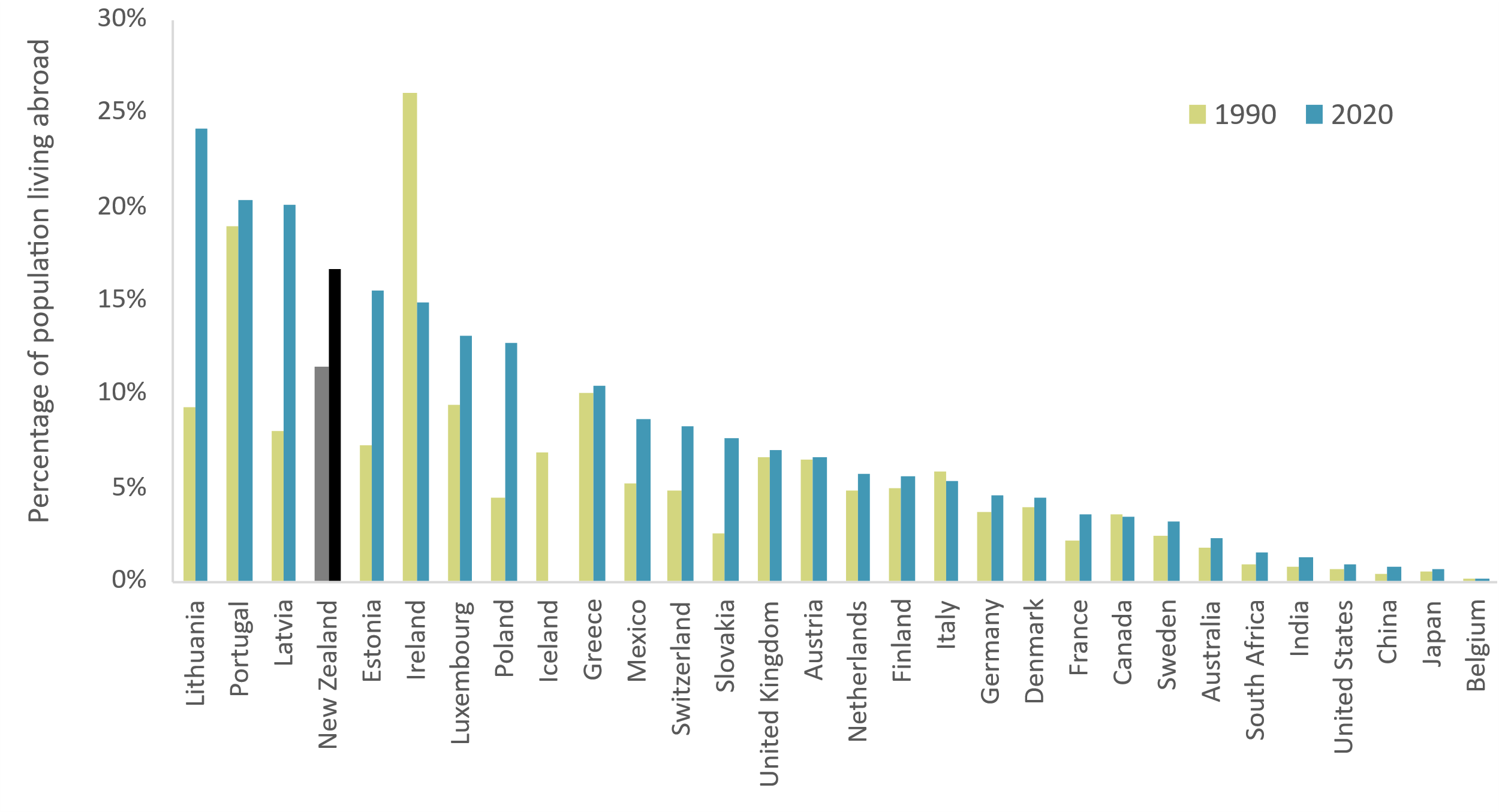

When I was on the Small Business Council and looked at the question of skills and our constant need for migrants, I was struck by two apparently conflicting statistics: first, the very high proportion of the population who like me were born outside New Zealand (28% according to the 2023 Census); the second, that there are now almost a million Kiwis abroad, making us one of the largest diaspora in the world.

It seems to me we've got something going on in our economy and our incentives which are pushing people offshore even though at the same migrants are required to fill skills gaps.

(New Zealand Productivity Commission, Immigration: fit for the future, 2022)

(New Zealand Productivity Commission, Immigration: fit for the future, 2022)

A penal regime?

The current regime looks excessively penal when compared with Australia, for example, where the level at which you are required to make repayments is now A$67,000 Australian, about NZ$72,000 New Zealand, or three times the current threshold of $24,128 which the Government has frozen for four years as part of this year’s Budget. Once someone is earning more than $24,128 in New Zealand, 12% is deducted in student loan repayments.

The obvious incentive for people to go offshore is the opportunity to earn more money. Furthermore, their repayments are much less, even if interest is now payable.

For example, if someone with a $40,000 student loan goes to Australia, they are no longer are subject to the 12% deduction but instead, because their loan is between $30,00 - $45,000, they are required to pay at least $3,000 a year.

If they remained in New Zealand and were earning NZ$80,000 per annum, their loan repayments would have been $6,704 (12% of the difference between $80,000 and the threshold of $24,128). By moving to Australia, they are at least $3,704 better off through lower student loan repayments, even if their Australian income remains the same.

Incidentally in Australia, the student loan repayment amounts don't reach the10% maximum until you're earning close to the equivalent of NZ$180,000.

Compared with Australia our present scheme is problematic because it deducts too much, too soon meaning student loan borrowers are another relatively low-income earners facing high effective marginal tax rates.

Does the rationale behind the scheme remain valid?

What is the purpose of the scheme? Back in 1990-91 the rationale for introducing student loans was that free tertiary education was unfair because those who benefited could generally expect higher income over their lifetime. It therefore seemed not an unreasonable approach to ask them to make a contribution.

But times have changed. That gap between the expectation of what you would earn having tertiary education and not having tertiary education has narrowed in some cases.

Remember, this scheme is now 34 years old. So is its rationale still valid? Does it help drive borrowers overseas, so that we as a country lose skills and the benefits of investing in tertiary education? I look at our large diaspora and wonder.

How has Inland Revenue managed the scheme?

Then there's the question of Inland Revenue’s management of Student Loan debt. There was an interesting interview with Kathryn Ryan of RNZ late last year during which an Inland Revenue official remarked that many of the student loan borrowers they're talking to now are into their 40s and 50s.

Putting aside whether the borrowers had either forgotten about, or didn't realise they had, these obligations, this raises the question about how Inland Revenue allowed such a situation to develop.

Remember, there’s 24,000 overseas based borrowers with debt that's more than 15 years old.

Is it actually fair that new borrowers are copping it from Inland Revenue for its previous inaction? As I said to RNZ, I think there's enough here to perhaps warrant the Auditor General looking at the whole question of how the scheme has been managed.

Fit for purpose?

And then there's the differing repayment rates and thresholds relative to other jurisdictions. If we are competing for global talent - which we hear frequently - it seems to me that works both ways, and we also want to hold on to skills here.

In that context maybe we should be looking at our repayment thresholds and levels. Looking at Australia’s scheme once you crossed that A$67,000 (~NZ$72,000) threshold, your repayments start at 1%.

Compare that with someone here who's earning a third of the Australian threshold and is expected to pay 12% above the threshold. It seems to me that with such heavy repayments there are not a lot of incentives for borrowers to stay in New Zealand if they want to get ahead and purchase a home.

In conclusion, although it’s understandable Inland Revenue is taking action to collect long-term debt, I think this scheme is deeply unsatisfactory now. After 34 years we need to pull back and look at the wider picture of the scheme’s objectives and the issue of interest and penalties.

These have been levied extensively, yet we've got $2.3 billion in default interest and penalties. As I said to Lisa Owen, it's time to think differently.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā.

11 Comments

If they remained in New Zealand and were earning NZ$80,000 per annum, their loan repayments would have been $6,704 (12% of the difference between $80,000 and the threshold of $24,128). By moving to Australia, they are at least $3,704 better off through lower student loan repayments, even if their Australian income remains the same.

Does this include with the additional interest charged on the loan over the year period Terry?

Remember, there’s 24,000 overseas based borrowers with debt that's more than 15 years old.

Is it actually fair that new borrowers are copping it from Inland Revenue for its previous inaction?

I'd say it is entirely fair that those who have not been fulfilling their duty to pay of their loans to be called in and raked over the coals. A loan is a loan, nobody can deny they were told they have to pay it back, they had to sign legal documents confirming so, abdicating all deniability.

I would think that if there was a threat of bein stopped at the border, then either 1./ People would never come back or 2./ They would actually pay their loan down for risk of bein held at the border should they have the likes of a family death and need to attend an NZ funeral etc. So far we have seen a large uptick in repayments form overseas student loan holders, so enforcement is working.

It's really hard to feel sympathetic to the borrowers upset over student loans when you and yours have been forced through the mill and suffered the extra 12% tax. It hurts, but it's done.

And I'm really unsympathetic to the but we didn't realize brigade.

That number of overseas defaulters, while big is surely only a very small percentage of the total loans. Which everyone else is paying off or paid.

The current system seems to be hell bent in driving people offshore.

With the level of default we need some teeth. Mum and dads house as security or surrender your passport till its payed off. Dont want to do that ...go somewhere else and study (pay international fees), or work part time and study part time and pay it off. If there are less students, we need less universities so be it. We are probably over burdened with to many Tertiary institution anyway.

Problem is that the University is not driven to cut cost, to act more efficiency and so forth because it has a subsidised guaranteed customer base.

If you want an example of how good and cheap (free) education can be, direct your kids (or yourself) to the excellent Kahn Academy.

Then try mentioning it to their teachers - in my experience they don't want to know, its too much of a threat.

Khan Academy | Free Online Courses, Lessons & Practice

Wow, brilliant analysis and commentary on the issues around the student loan scheme.

Why do none of our government's see fit to review these kinds of big issues to determine whether something 30+ years old is still fit-for-purpose?

In my UBI exercise, the student allowance scheme would be scrapped. I hadn't considered student loans - as in theory they are not a 'cost' to taxpayers, but this consideration is really worthwhile;

https://www.interest.co.nz/public-policy/133744/what-do-you-get-when-yo…

In theory, I'd be more inclined to make tertiary education fees-free, via government scholarship, for those qualifying under some system of entrance standard (a combination of secondary GPA + a standardised test related to the area of study).

Student loans would then only be needed/available to those not pre-qualifying for the fees-free scholarship.

Student fees are paid by Govt from the annual Govt budget when students go to college. They are a direct expense. When loans are agreed, an asset is added to the Govt balance sheet. As loan repayments are made, this asset is reduced in value. There is no revenue from repayments. The asset is just marked down.

Govt could therefore wipe all student debts tomorrow and the impact would be a marking down of Govts financial assets by about $10bn. No lost revenue, just a write off. Govt would still have a very positive net financial worth.

If Govt wanted to do something positive to get the economy moving, this would be one of the most obvious moves. Labour should campaign on it (and guaranteed training/free uni/work/apprenticeships for youth of course).

Writing off creates an argument to write off other 'govt to citizen' debt, such as Welfare debt, Child Support debt, Tax Debt, Court Fines and reparation, kainga Ora debt, ACC debt and Legal Aid debt.

Comes to about $18.8. Pretty shocking the amount that student estimate figures range from $11.98 to $16 Billion.

Most people in general, and NZ economists and commentators in particular, have no clue about how a fiat currency monetary system works and it leads to fundamentally stupid economic policy choices and discussions.

The pettiness and barriers to entry created by our public institutions are costly and economically damaging, and yet we can't get enough of it.

The wizard said to the farmer - "I will grant you any wish, but whatever you wish for your neighbor will get two of. The farmer thought for a long time and then replied "take out one of my eyes".

Commercialisation of education has resulted in a plethora of courses and qualifications that are “lifestyle”, “ follow your passion” or “you must love your job” based, regardless of whether the end result is employability, which is leading to disappointment (including in my own close and wider family group) and resentment and concern at the level of debt incurred for the privilege.

The diaspora are complaining but are seemingly getting a better deal than their on-shore counterparts, so the question is whether the NZ based repayment obligation (at 12% capital repayment, interest free) is driving people offshore – Terry you conclude this is happening but there are many other factors responsible for Kiwis, of all ages, leaving.

And to give remission to the diaspora simply cos they are “over there” is not fair to those who have dutifully paid their loan off (whether here or there).

However agree the scheme including the application of fees to unproductive courses, needs review.

One thing wrong in our understanding of our diaspora is the weighting given by the huge percentage of it living and working in Australia. No one has official figures on this (eg, SNZ etc), so I slugged it out with all large and medium countries own Census data, where nationality is recorded - most in fact do this. Australia has numbers on us, I did this in 2021 to make this point to the Productivity Commission, who I found have no data sheet for the numbers they produce. At that time, ex-Australia, our diaspora was less than 3%, the same as the one the Commission shows for Australia. We kid ourselves a bit about this - I'm afraid we are not as exceptional as we like to believe. The diaspora ex-Australia is pretty standard. If you think about it, there are good reasons for this, the main one being how hard it is to get into and stay working in most other countries for a Kiwi, apart from Australia.

A diaspora is 'NZ-born, usually living abroad', and doesn't include the 'float' of working holiday people. After about 550k in Oz, 60k the UK, 20k the US and 15k Canada, the numbers per country shrink rapidly. I estimate ex-Australia, in 2021 they were around 130k. Against a 5.2mill population then, that's 2.5% for a meaningful 'diaspora - still under 3% at 150k ex-Australia. Australia in my view 'doesn't count' in the usual meaning of a far-flung adventurous population. You can come home to the folks for a weekend visit from everywhere substantial but Perth.

My point is not to deny great numbers of us are working elsewhere, but to show that Australia is about 80% of the total and needs us to think clearly about that. It's Australia that really matters in IRD tax terms by number of defaulters, perhaps not by value.

What might help is making some value judgements about the sort of skills we need and incentivising those by giving free rides through training to people doing things we need as a country - if and only if they stay in the country as practitioners for a specific period after they qualify.

We desperately need medical people, building trades, engineers and the like, and incentivising people to enter those professions is sensible, even if it has not been the New Zealand way.

I can also hear the screams from sectors that consider themselves essential to the country's functioning.

But do we need more lawyers, accountants, urban planners, accountants, administrative staff of all types, and the like when there is an AI-driven revolution going on in so many professions that will automate away so much currently human activity?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.