A capital gains tax that applies interest to gains accumulated before an asset is sold would align with New Zealand’s principles-based regime, an international tax expert told Treasury.

Michael Keen, a former deputy director of the International Monetary Fund’s Fiscal Affairs Department and university academic, gave a public lecture at the Treasury on Wednesday.

He was responding to Inland Revenue’s recent long-term insight briefing which looked at how to design a “durable” tax system which could respond to fiscal pressures.

Keen said this should be about establishing a set of stable tax bases which could be adapted to meeting changing revenue needs and distribution priorities.

“Underlying that is the cruder question of, well, if New Zealand had to raise more revenue, how would you best go about it? We know there are these fiscal pressures, where might the money come from if needed?”

There could be a need to raise almost another 6% of gross domestic product to cover the rising cost of healthcare and superannuation by 2060. This could be met through policy reforms, improved efficiency, higher taxes, or some combination of all three.

Keen didn’t give any particular policy prescription as his talk was focused mainly on technical aspects of his tax design research. However, he did drop hints about using GST, user levies, and an advanced capital gains tax to widen the revenue base.

While he didn’t speak about these at length, the economist and tax expert said it was best to start with user fees, corrective taxes, and taxes on economic rents as these improved the market allocation of resources.

This means things like road user charges and co-payments for public services, excise taxes on things like emissions, alcohol, and tobacco, and (theoretically) excess profits above the necessary return to incentivise an investment.

But those taxes aren’t generally enough to run a government or meet distributional needs and so policymakers turn to more “distortive” taxes — those which may worsen market allocation.

‘Please don’t change!’

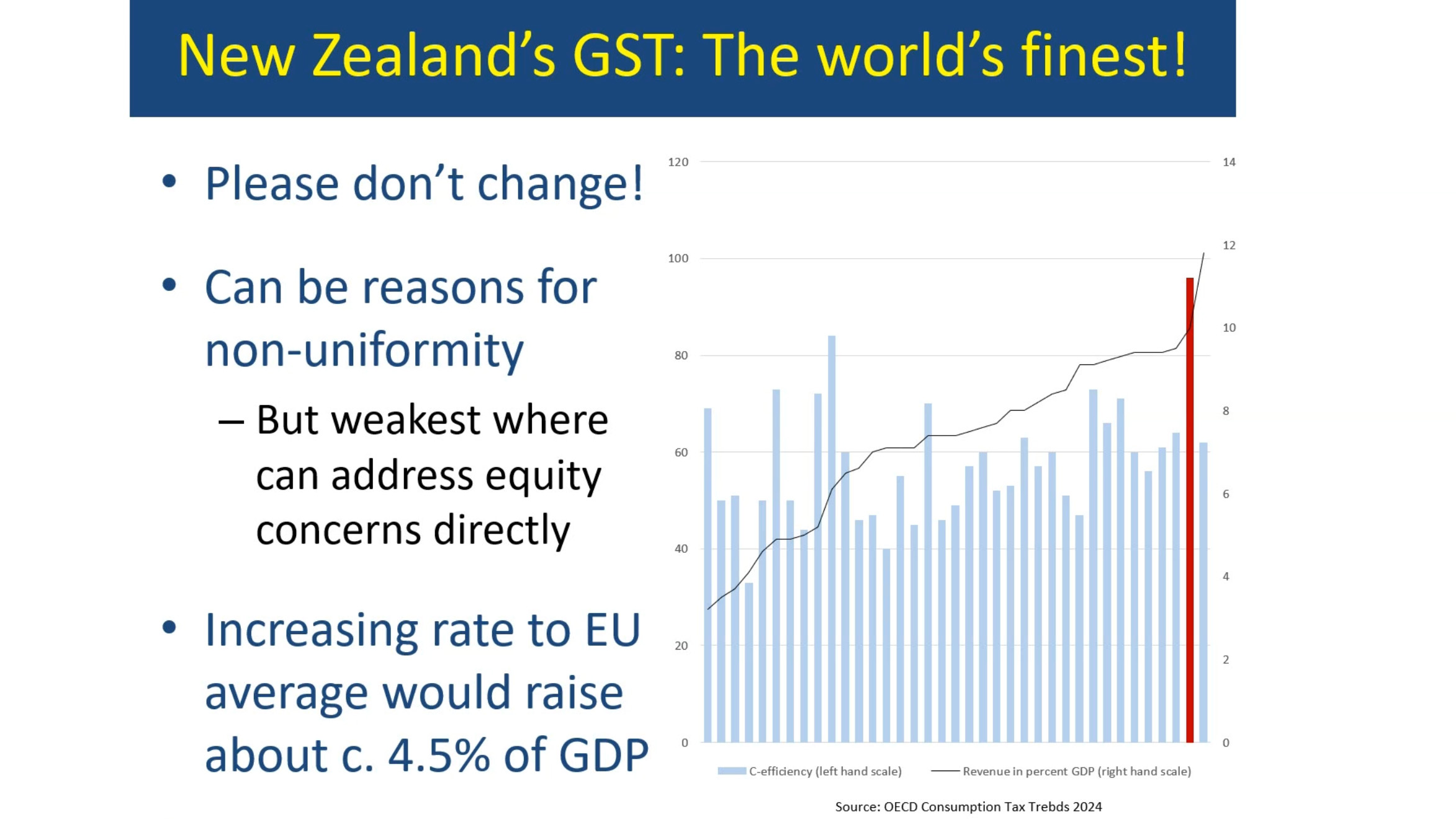

Like many tax experts, Keen heaped praise on New Zealand’s comprehensive GST regime and implored policymakers not to mess it up.

“GST, well, I just want to say, don’t change it. Not much more to say about that… it’s pretty amazing, really, with a rate of 15% that you’re right up there with [such] a broad base. So don’t change it.”

The European Union’s average consumption tax rate was 22%, although often with carve outs and exemptions for various products and services. New Zealand could raise roughly 4.5% of GDP by lifting GST to that same rate, Keen said.

But a higher rate would likely require an offset for low income earners such as a means-tested tax credit, a flat payment to eligible groups, or a smart-card which deducts GST at purchase.

In its insight briefing, Inland Revenue modelled the possibility of raising $5 billion annually by lifting GST to 18% and providing a tax credit to families earning less than 60% of the median disposable income.

However, Keen focused most of his speech on the absence of a comprehensive capital gains tax, which he saw as being a flaw in New Zealand’s otherwise excellent tax regime.

“New Zealand's principle-based income tax is based on the idea of a comprehensive income tax. That is, a tax on income from all sources added up to which you apply a progressive tax schedule,” he said.

And any textbook description of a comprehensive income tax base would include accrued capital gains as a form of income, whereas New Zealand taxes only certain capital gains.

It would make more sense to pass a law saying everything is subject to a capital gains tax and then list whatever exemptions were seen as beneficial or politically necessary, Keen argued.

“All I can do is put that thought in your mind. In terms of the politics of going in that direction, I'm going to be agnostic and even more ill-informed than on other topics”.

Living ‘the high life’ tax free

Many experts have encouraged New Zealand to broaden its capital gains tax base. Keen echoed these voices and spent a portion of his talk discussing a technical variation on the tax.

One complaint about CGT is that it is only paid when an asset is sold. This encourages owners to hold onto businesses or properties when it might otherwise be more efficient to sell.

Economists call this “the lock-in effect” and it reduces investment efficiencies and makes revenue earned from capital gains unpredictable. But it also creates equity problems.

“Wealthy people can have unrealized capital gains. They might want to borrow against those gains. And, you know, live the high life without, without incurring a [tax] liability,” Keen said.

Depending on inheritance tax settings, unrealised assets may be able to be passed onto the next generation to borrow against without ever being properly taxed.

“So taxation on realisation rather than accruals, as currently done, creates both these efficiency and these equity issues,” Keen said.

One way to address the problem is to tax gains when an asset is sold but also to charge interest on the liability as it builds up.

In practice, investors would accrue an annual tax obligation on their capital gains but could defer payment until sale, with interest added, removing the incentive to hold assets purely to avoid tax.

Keen said this would be straightforward for publicly traded assets with clear market prices, but more complicated for privately held ones. In those cases, the tax could be based on an assumed rate of return each year, with liabilities calculated that way.

The tax expert admitted this type of policy had only been tried once, in Italy in the 1980s, and had failed. But he thought it may be possible with more advanced technology and systems.

“I, at least, find it surprising that people don't talk more about these schemes,” he said.

A well-designed capital gains tax would also reduce the need for wealth taxes, which aren’t common in other jurisdictions and are more distortive than alternatives.

“If you have a proper tax on capital income, including dealing with unrealised capital gains, what does a wealth tax add? And I think the answer will be, not much.”

47 Comments

I have no doubt that labor will bring in a CGT ... but just for the votes.

Dishonest politics at it's finest.

And now for the exemptions -

Family home?

Farm?

land owned by a Maori?

Charity owned land

Next.....

Then try and define each

Bet you a bottle of red it will target only property. Farm prices will boom and there will be a debt bubble.

property meaning what?

NZ already has wealth tax exerted on property by way of local councils largely apportioning their rates calculated on value. However they try to obfuscate it, the fact remains the higher the value of your home the higher the amount of rates you will pay. A wealth tax or a CGT on property that is based on an estimate of value obviously would rely on who exactly arrives at the relative value. New Zealand courts have long needed to consider cases that present fickle, arguable and plainly inaccurate valuations of just about any commodity you can think of. But in terms of property values you would just need to refer to the multitude of such disagreements in the courts over Canterbury EQ claims.

"the fact remains the higher the value of your home the higher the amount of rates you will pay. " not quite. rates are set by multiplying the rateable value, usually called CV, by the rate per dollar of CV. If your rateable value goes up the council could quite easily lower the rate per dollar of CV to maintain constant rates. Never going to happen. Councils want more and more money so the product of your rateable value and rate per dollar of CV will invariably go up. If your rateable values go down in general all the council does is change rate per dollar of CV to maintain the same or increased revenue as they are want to do.

To keep it to the basics, consider this then. Two residential properties in Christchurch, side by side. Same sized sections, structures and street frontage. One pays annual rates $10,946.70 the other $5,790.87. The difference being the former is a new house, a rebuild caused by the earthquakes. Now if that is not a result of assessing rates predominantly by value then what is it. One thing for sure seeing as both household have the same number of occupants it is certainly not based fairly on goods and services provided which then provides for central government to further the distortion and inequity by collecting GST over the top of it all.

OK. I see where you are coming from. I'm used to rates being based on land value, NP and some other councils. Chch and others are on land plus improvements. Perhaps there needs to be two rates. One for land and one for improvements. I don't know how many new builds there were in ChCh since the earthquake but I should imagine in the last ten years the council revenue from rates jumped by massive amounts. Appears not much different from other councils.

Always amazes me that almost everyone agrees that Aotearoa GST is the best, often due to it's comprehensive broad nature.

Then they suggest the need for another tax, but let's allow all these exemptions.

Surely the learnings from GST is no bloody exemptions.

In hindsight everybody might agree, but I expect that would be a different story if we were trying to bring GST in today.

Concessions required moreso to get us fickle voters onside.

And then they complain that food is more expensive than overseas where it is exempt.

It is always a income problem. Never a spending problem

Too right, means test super and do away with gold card

I never understood why old people living in million dollar mansions needed free bus fares just so they could leave the Volvo in the garage.

I can understand why they want live in a big house and only use 2 rooms.

CGT on unrealised capital gains for residential housing but exclude the home you live in. I buy a house to live in, not for its capital gains. If various local and central govt policies over decades have lead to high land/house price increases then don't come to me for CGT in the house I live in. Any other house/dwelling tax it on unrealised capital gains, just like many shares are taxed on unrealised gains.

An absence of tax drives investment to that tax free 'opportunity'

Have a quiet ponder what that might cause and the problems we currently have in NZ re productive investment.

Agree.

However the statement below casts a big shadow on his idea - he needed to develop this further. Saying 'he thought' is not what an expert needs to come up with.

The tax expert admitted this type of policy had only been tried once, in Italy in the 1980s, and had failed. But he thought it may be possible with more advanced technology and systems.

The last untaxed frontier in NZ is property. Its tax free gain nature is why so many over invest in it. With a side order of forcing the pace of inflation to make it stack. In effect keeping the tax free gain and socialising the tax paid loss. Aussie are introducing a tax on implied gain and a lot of speculator noise over there on this.

So same here...or just a simple land tax.

Cant see Nat's bring this in, and if the Lab Grn, TPM crazy brigade get back in who knows.

New Zealand can't squeeze income earners any harder, we're going to have huge trouble looking after our ageing population without some sort of asset tax. CGT won't raise enough revenue so realistically we're looking at a wealth tax, property tax or land tax - the latter being our best option. Timid tweakers like Michael Keen are becoming irrelevant to the discussion.

"going to have huge trouble looking after our ageing population" - how are that ageing population going to afford a land tax?

- Sell their property and downsize, factoring in some of the profit to afford the land tax

- Reverse mortgage

- Sell an investment property to maintain their own home

- Sell other investments

- Continue working (many are)

Plenty of options for them to use. Millennials will be forced to regardless by necessity so it is only fair that all of the capital gains made by current retirees be tapped to fund the support they need. It isn't equitable to lump everything on current workers.

While many before them may have had their cake and eaten it, the buck needs to stop. Nobody wants to pay more tax, but people need to in order to fund healthcare and pensions.

Many old people have little other than the family home. Changing the tax treatment dramatically will make them dependent on the state. These people have done little wrong, they retired with a home and then expected to live off NZ super.

A reverse mortgage will only last so long.

Downsizing often doesn't yield much after real estate commissions and moving costs.

Long before we organise the method of implementation wouldn't the logical process be to have an honest conversation (and agreement) about what the purpose (goal) of the economy is?

The trouble is convincing the heavily ingrained vested interests that they need to lose something to benefit the majority. We have generations that have worked to provide a better life for the next, and currently we have a generation or so that have much, and will do anything to prevent relinquishing any part of it for the greater good.

Will I be able to claim an annual loss for my Wellington property dropping in value since I bought it?

Thought not.

I guess rents will rise faster when values go up because owners will have an annual tax bill so will need to raise funds from the users of their assets. The only way this won't happen is if even more people vote with their feet so values will plateau.

As I read his suggestion, the answer would be yes - as the tax owing is accrued (until sale of the asset) - both losses and gains would be part of the accrual. If at sale you are under water in terms of the accrual, my proposal would be that your tax would be zero rated. In other words, no gain, no pain - but no refund for an investment that lost money. If the latter were the case (a refund) - everyone would spend more than a property's market value in order to get the refund :-).

.

So the government would take, but not give? On that alone this'd lose my vote. Taxing unrealised value gains on property would end up displacing people from their homes, or in the case of relationship break-ups, prevent them from being able to buy new homes. Nothing less than destructive for people.

And we get back to the basic concept of how money works in the economy. My view is tax those who profit most (tax where the money is going); like taxing the banks for all the profits they make from their mortgage portfolios, and the property investors and landlords.

No, it would not displace people from their homes, as the tax is but an accrual - due only on sale of the asset. In the case of a relationship break up. one could write the tax law such that on sale of the asset under the relationship property act - each partner takes a 50% accrual forward on their replacement asset.

One can write laws in anyway one wants in order to make the tax as equitable as possible.

The property market is moving the way it is is due to the government failing to regulate it properly. I'm with NigelH above, any appreciation is a consequence of the government's failure to regulate the market and CGT will not achieve that.

An accrual over time could just as easy see the tax bill swallowing up the majority of a sale amount. Trusting the politicians to create a 'fair' tax is like trusting a thief to keep his hands to himself in a toy shop. the only version of 'fair' they understand is when they profit.

Assuming each person can afford to use the proceeds to buy another property to live in.

In practice, investors would accrue an annual tax obligation on their capital gains but could defer payment until sale, with interest added, removing the incentive to hold assets purely to avoid tax.

Great alternative concept to widen the tax base, particularly given our outsized investment in real estate and the fact that we have no inheritance tax. Very simple to administer.

Much preferred to a GST increase as a means to raise more revenue - with the 'targeted' tax breaks for lower income households. Too complex.

And definitely, the government needs to seriously consider widening that tax base to collect more revenue - it isn't going to come from "growth".

Most own investment owned by a company, owned by a trust. "Owner" dies and trust has new beneficiaries (children etc). In effect benefits transfer but owner ship does not. Equals no tax to pay... There will be a million other combinations of avoidance as we have had in the last few decades, with the weakest of statements "I did not mean to make a gain" equaling no tax to pay.

This is why it needs to be a land tax paid quarterly. Any beneficiary legislated to be clearly tagged for tax responsibility. Nil avoidance possible. Very transparent. Foreign based tax payers (avoiding paying tax in NZ), can be hit with a higher rating.

Again, one can write the tax law in any way you want to thwart avoidance. In fact, I've often wondered why our trust laws allow folks to put residential property assets in trust anyway. The only benefits of doing so to my knowledge are purely for tax avoidance reasons (or to qualify for taxpayer subsidies), or to try to protect such assets from creditors. Neither of which as reasons make any moral sense to me.

My Mum after her cancer diagnosis thought, bless her cotton socks, that putting the house into a trust would secure it from the clutches of her replacement.

Her replacement?

Father's new wife after mother passes away.

My mother had the same plan and the trust is still operating even though my father is now in a retirement village and no new wife will eventuate (the trust loaned the sale proceeds to my father so he could buy his "right to occupy").

Ah, I get it now. Hadn't ever considered that, but sounds like a legitimate reason for a trust ownership structure.

Totally the case.

Then we have the incentive it gives politicians to create inflation. Inflation as a tax and more inflation = more tax.

Care to define inflation?

Vapor created money every time the banks lend on a mortgage. This is not money from deposits, the banks just "magics" it into being in their computer system. Also referred to as increasing the money supply. Assume finite goods, but more money chasing it, eg...coffee is $5, then $7, then $9 and so on and so on.

I often explain by way of the game monopoly. No inflation due to fixed issued notes.

The banks may 'magic' money into existence but what do you define as inflation?

The banks can 'magic' money into existence and we could have zero/negative inflation....unfortunately the term "inflation" is misused and misunderstood....what most appear to be currently concerned about is 'the cost of living'....and that is understandable, however there is much less widespread concern when 'inflation' in the cost of assets (i.e. housing) appears.

'Inflation' is a feature of the current model....seems odd to complain that we are more than achieving our targets.

the affect of an increasing money supply.

If interest on imputed gains is charged, does it also mean you get tax credits if your capital asset depreciates, the way residential property is at the moment, and will the costs of protecting the asset's value (maintenance) be tax deductible?

If not, it would be signally unjust, and if so it creates a great deal of complexity.

The author did not suggest any interest (on accrued gains) be charged.

"One way to address the problem is to tax gains when an asset is sold but also to charge interest on the liability as it builds up."

"In practice, investors would accrue an annual tax obligation on their capital gains but could defer payment until sale, with interest added, removing the incentive to hold assets purely to avoid tax."

Oops, missed that. Don't know that such a tax should be designed for the purpose of dis-incentivising folks not to "hold" assets. What's wrong with holding assets, particularly if they are generating an income.

My thought is that widening the tax base and design of said tax, should simply have the objective of raising more revenue. The beauty of an accrual proposal is it is broad-based (every property asset is treated the same) and collection on sales will accelerate in the short/medium term as the boomer generation downsizes and/or passes on.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.