The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (the OECD) has just published its Tax Policy Reforms 2025. The report is intended to provide comparative information on tax reforms across countries and the latest tax reform trends.

This year's edition focuses on tax reforms introduced or announced during the 2024 calendar year in 86 jurisdictions. This broad scope makes it such a fascinating report as it gives insights and very interesting data on what trends the OECD are seeing and how other countries are adapting their tax systems to particular challenges.

Key trends

The first conclusion was that after 2023 marked a turning point away from the broad tax relief measures seen during the pandemic and the subsequent period of inflation, 2024 solidified that trend with a mix of rate increases and targeted tax support across all major tax types.

“High levels of debt coupled with the significant emerging spending needs relating to climate change, ageing and in some countries, increased defence spending has meant that jurisdictions of all income levels have adopted strategies to mobilise more revenues.”

Rising cost of climate change

In short, we're not alone in realising that we've got issues coming down the path. I do find it interesting that while the debate in New Zealand has focused on the increasing costs of superannuation and health care, the OECD executive summary references climate change first. Although we definitely face future issues around changing demographics with rising superannuation costs and related health care costs, the immediate expenses in relation to climate change are arriving now.

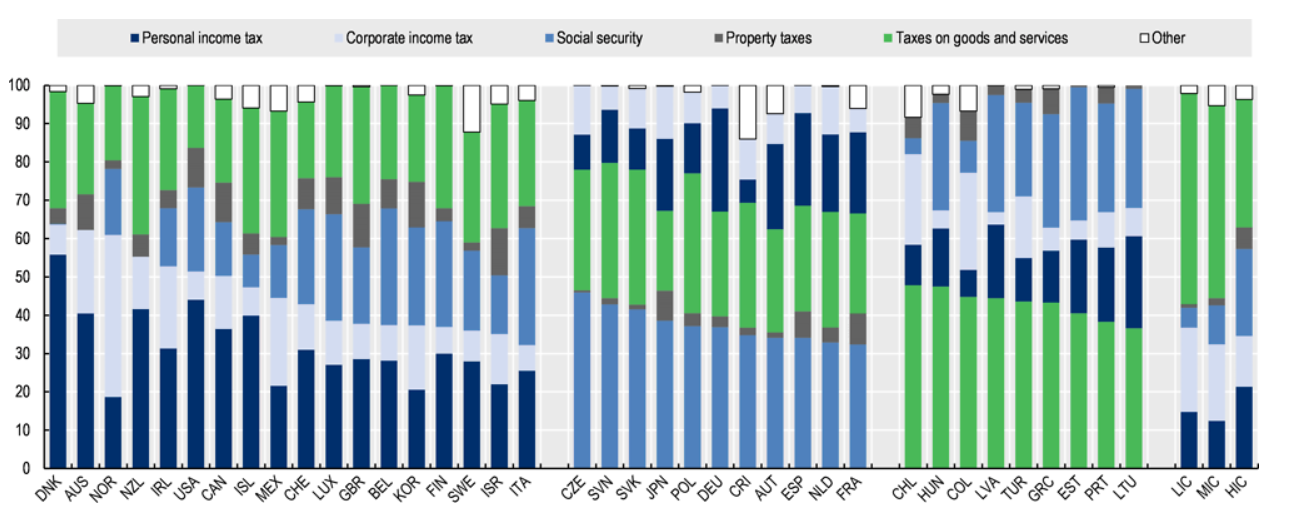

Figure 2.2. Tax structures in 2022 (as a % of total tax revenues)

Widespread tax and social security increases and base-broadening

According to the OECD, during 2024 more jurisdictions raised their top personal income tax and capital income tax rates than in previous years, “often to generate revenue or enhanced tax progressivity.” This also applied with social security taxes, another area where our system is a bit of an outlier. Almost all other OECD jurisdictions do have such taxes where they represent upwards of 25% of the total tax take.

According to the OECD, social security contribution rate “increases remained widespread and amid rising health and ageing-relating spending”. Meanwhile social security base broadening measures included focused on increasing maximum contribution thresholds and expanding the range of covered income, whereas based narrowing measures targeted specific types of workers or sectors to stimulate labour force participation.

ACC increases

Although we don’t have a general social security tax New Zealand is noted as one of the countries increasing their social security contribution rates during 2024. What the OECD is referring to here is ACC, where levies were increased by 5% with further increases set to occur in the next two years. These increases were announced in late 2024 and in case you missed the detail they are as follows:

|

Year |

Levy rate (GST inclusive) |

|

1 April 2027 to 31 March 2028 1 April 2026 to 31 March 2027 1 April 2025 to 31 March 2026 1 April 2024 to 31 March 2025 |

$1.83 per $100 $1.75 per $100 $1.67 per $100 $1.60 per $100 |

It’s likely many haven’t noticed these changes because they are deducted through PAYE, so they are one of those unknown tax increases (like bracket creep) which happen without many realising.

Plenty happening with GST/VAT

I found the section on Value Added Tax (VAT) or GST one of the most interesting. As the OECD notes the use of reduced VAT rates/exemptions as a policy instrument remained widespread in 2024.

“In almost all jurisdictions, governments apply reduced VAT rates or exemptions, most often intended to reduce the tax burden on essential products such as food, healthcare, education and housing. Reduced VAT rates were also used as a means of supporting certain sectors, such as sports, tourism, culture and agriculture.”

In addition, many jurisdictions continued to use targeted temporary VAT rate reductions as a tool to cushion price increases on specific products or as part of support measures in response to natural disasters. (An interesting idea but probably not practical here).

By contrast to the single all-inclusive 15% GST rate applicable here there's a lot of tinkering that goes on in other countries around applying zero-rating. For example, the UK extended zero-rating on menstrual products to include reusable period underwear. Over in Ireland, it reduced the VAT rate on the supply and installation of heat pumps from 23% to 9%. Ireland also extended zero rating on the supply and installation of solar panels for private dwellings to include schools.

As we discuss below GST/VAT is an efficient revenue raiser which is why Estonia raised its VAT rate from 20% to 22% to help rebalance its general budget. Similarly, Singapore has been gradually increasing its VAT rate. On the other hand, ten countries increased their VAT registration thresholds to support small enterprises.

Inflation and GST/VAT

The report notes Luxembourg previously lowered their standard rate of VAT to 16% to help deal with inflationary pressures. In 2024 the rate was raised back to 17%. I've often thought because it directly affects spending, VAT/GST is something that could be used to better target dealing with inflation rather than through interest rates.

Overall, it’s interesting to see the very active use of GST/VAT for public policy purposes

Going against the trend

Many jurisdictions increased taxes on tobacco, alcohol and sugar sweetened beverages, although we are noted as going against the trend in relation to heated tobacco products. By contrast sixteen countries including Canada, Ireland, Spain and the United Kingdom, implemented or announced increased taxes on tobacco products to improve public health and raise revenue.

Fuel excise taxes and expanding carbon taxes

Another notable shift according to the report was the move away from temporary fuel tax reliefs towards increases in fuel excise taxes. For the second consecutive year, high-income countries, and we are included in that list, “continued to strengthen explicit carbon pricing…with several increasing carbon tax rates or expanding their scope to include new sectors such as international shipping and agriculture.”

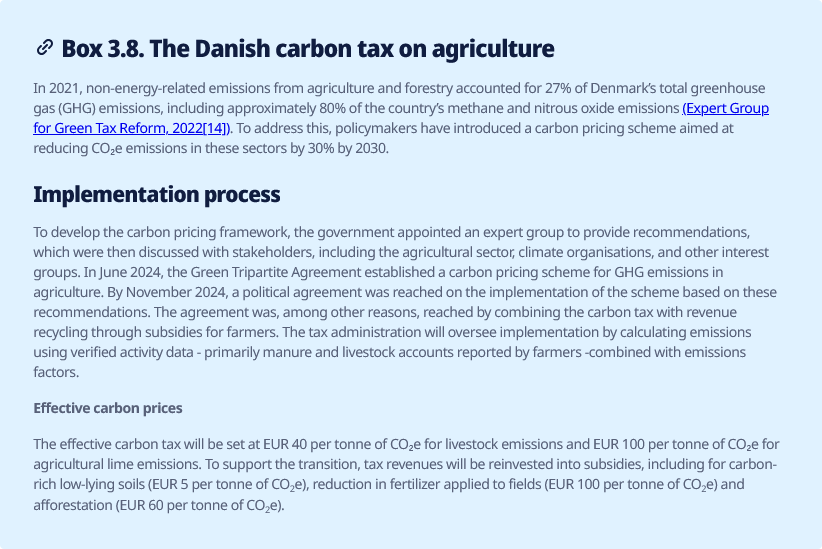

A carbon tax on agriculture – the Danish example

Something which will probably horrify farmers is Denmark’s carbon tax on agriculture aimed at reducing CO2 emissions from agriculture and forestry by 30% by 2030.

The Danes propose recycling the tax revenue into subsidies, including for carbon rich, low lying soils, reduction in fertiliser applied to fields and afforestation. I consider environmental taxes have a big role to play in climate adaptation, but my firm view is they are recycled to mitigate the effect of transition to a lower carbon economy.

Corporation tax trends

In 2024 more jurisdictions increased corporation tax rates than reduced them for the second consecutive year. It therefore seems the long-running downward trend in corporate income tax rates has halted or is reversing. That said, the OECD noted “many governments continue to prioritise support for investment”, such as the Investment Boost in this year's budget. Governments continue to offer tax incentives for investments, particularly in research and development, clean technologies and strategic sectors.

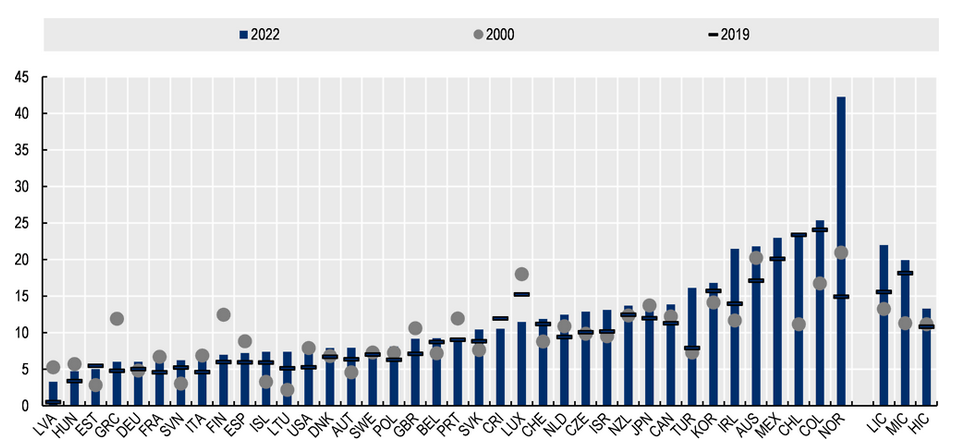

The report notes there are continuing wide disparities in corporate income tax (CIT) revenue across countries particularly between low-income countries where CIT represented 22% of revenue in 2022 compared with 13.3% in high-income countries. At 13.69% we’re slightly above the OECD high-income average but quite some way below Australia’s 21.814% in 2022.

Corporate income tax revenues as a percentage of total tax revenues

According to the OECD the average combined rate was 21.1% in 2024, which is down from 28% in 2000. Three countries (Austria, Luxembourg and Portugal) cut corporate tax rates in 2024, but five, Chechnya, Iceland, Slovenia, the Slovak Republic and Lithuania all increased their corporate tax rates.

Small business measures

The report discusses the wide range of incentives for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), which is very interesting to see. Several jurisdictions have specific incentives or tax rates for SMEs with the look-through company and shareholder-employee regimes being the closest comparison.

The report noted in relation to research and development incentives that “on average SMEs benefited from higher tax incentives due to the preferential tax treatment specifically aimed at smaller firms.” As noted above we typically don't have such measures but arguably if you want to lift New Zealand’s productivity, specific incentives for SMEs is perhaps something worth considering.

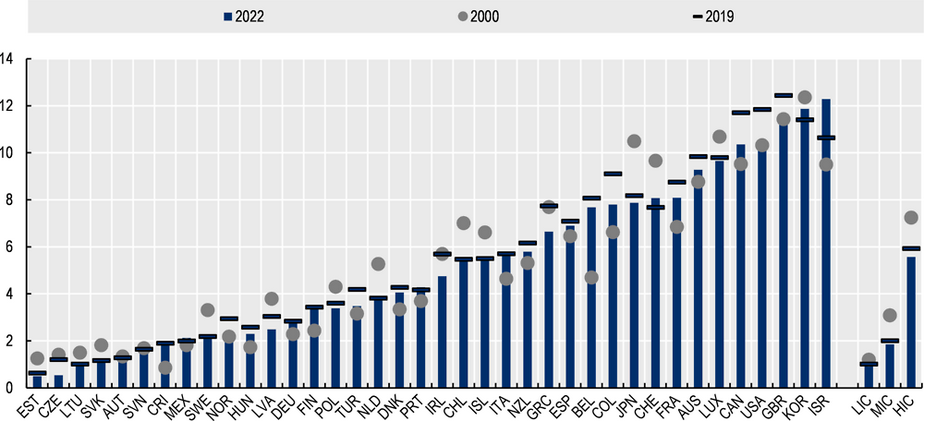

Property tax reforms

This section covering property taxation includes not just real property, but also capital taxes. Here the trend was predominantly focused on rate cuts and base narrowing measures. These measures were designed to make housing more affordable, simplify property tax systems and encourage investments. Where property tax increases did occur, “they were primarily driven by the need to raise revenue and address equity or fairness concerns.”

According to the OECD property taxes continue to make up a relatively small share of total tax revenues in most countries, although significantly more important in high-income countries where they averaged 5.6% of total tax revenues in 2022. (Perhaps surprisingly, New Zealand sits at this average).

Property tax revenues as a percentage of total tax revenues

As always, a fascinating report to review with plenty of detail and policies to consider. Well worth a read.

Yeah, nah, definitely maybe – what do the public think about capital gains tax?

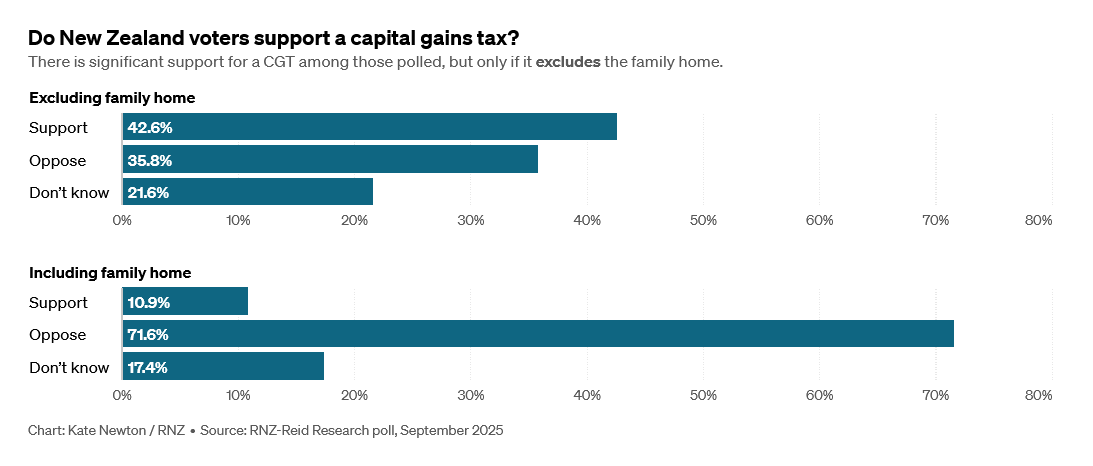

Moving on, a recently released RNZ-Reid Research poll gives an indication where the public stands on capital gains tax. The headline summary is a plurality support it, so long as it doesn’t include the family home.

Of interest here is the relatively narrow plurality in favour and the over 20% “Don’t knows.” So very much up for debate it appears.

Happy 40th Birthday, Australia’s CGT

Saturday 20th September was the 40th anniversary of Australia introducing its CGT. When considering a CGT, we have 40 years of evidence from our closest neighbour as a counterfactual. If a CGT was as dire an issue a problem for our economy as its opponents often suggest, then we should be richer than Australia and have higher productivity. However, the objective evidence points the other way. That's not to say that introducing CGT will immediately improve our productivity, but it should mean that more capital is deployed more effectively.

Yes, Australia's CGT comes with great complexity, but that complexity is all around the world. On the issue of complexity, I think it's also a relativity point. If Australia, which is our closest peer economy has it and we don't, then this is where relative efficiencies come into play. Are we more efficient and productive than those economies because we don't have that complexity? My view is the evidence is our productivity is already falling behind so arguing CGT inhibits efficiency and productivity is not necessarily true. If other countries consider they need to have a CGT for a variety of reasons beyond simple revenue raising, then that is something we should factor into our thinking.

An international perspective on our tax system

Talking about future tax changes it so happens that the Tax Policy Charitable Trust with the help of key sponsor Tax Management New Zealand brought down guest lecturer Professor Michael (Mick) Keen for a couple of lectures on the topic, firstly at Treasury in Wellington and then in Auckland.

Professor Keen is a very interesting gentleman who is a former Deputy Director of the Fiscal Affairs Department at the International Monetary Fund (the IMF). During his time with the IMF, he led missions to over forty countries, so he has a great breadth of experience. Currently, he is Ushioda Fellow at the University of Tokyo.

I attended the presentation he made to the Tax Policy Charitable Trust in Auckland which was followed by a panel discussion with Aaron Quintal (Tax Partner, EY), Robyn Walker (Tax Partner, Deloitte) and Kelly Eckhold (Chief Economist, Westpac). As you’d expect it was a fascinating event.

If you think our ageing challenge is big, at least we’re not Japan

Professor Keen began by praising Inland Revenue’s long-term insights briefing, for actually considering the coming demographic fiscal issues. Japan where he now resides also has an ageing population and its demographics are horrific. Furthermore, its government debt to GDP ratio is over 200%. Japan is facing major issues but, in his view, the Japanese policymakers just weren't willing to engage on the topic, whereas we were.

Professor Keen thought our tax system on the whole has an underlying logic to it. He particularly liked our GST system for its comprehensiveness “Don't touch it, it's fantastic.” In relation to the topic of CGT Professor Keen noted that it could complete our comprehensive income tax framework. He suggested that any CGT adopted should be inclusive with exclusions as an approach, rather than where we are at the moment, where it's exclusive with inclusions (and there are more inclusions than many realise). Most comparable jurisdictions have already implemented a CGT regime along the lines suggested. I did get the impression he was surprised at how much of an argument went on around the topic.

GST at 22%?

In the following panel discussion GST was seen as the area where if we are going to raise additional revenue then GST must rise. Professor Keen noted that if we were to increase GST to the average European rate which is nearly 22%, that would raise 4.5% of GDP, a huge sum of money which would go a long way to resolving future funding issues.

The big “But” to raising GST is mitigating its effect on lower income earners. We have an issue with this already in our system as I've discussed previously. We would need to bring in much greater targeted relief for those most adversely affected by an increase in GST.

Professor Keen noted that Inland Revenue’s view was that GST could go up to 17.5%, but any higher may hit potentially significant public pushback. This is interesting when you think about European rates of 25% and higher.

It was a very interesting presentation by Professor Keen. It's always good to get an international perspective on our system. We get a favourable tick basically because we have a very good GST system, a reasonably solid basis of policy making and we are trying to address these coming fiscal pressures.

And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.

16 Comments

If the home is exempt from any new tax then non homeowners should have a tax break on any investment up to the value of a family home.

That would make it fair.

No chance. Pull the ladder up.

Interesting to see that New Zealand ranks in the middle for property taxes. The common belief here, is that taxes in NZ favour property owners.

I think you may find that property tax describes TA rates in NZ....I doubt you will find many who believe they are favoured in that regard.

"I've often thought because it directly affects spending, VAT/GST is something that could be used to better target dealing with inflation rather than through interest rates."

How would this work? Economy is overheated, starting to see inflation, increase GST to reduce demand, and that in itself causes inflation.

Absolutely not to raising GST. It is an extremely regressive tax and should be reduced over time. The tax burden in NZ must be carried by a broader base and not just consumers and income earners.

Progressive taxation should be the model we look to for increasing revenue.

Progressive taxes creates compliance issues, requires an army of IR lawyers and accountants and distorts good business decision making which becomes a negative to productivity.

30% tax on $30k is $9,000 (and you can tweak the system and give back via family tax credits)

On $500,000 it is $150,000.

Who is carrying the burden?

Probably the guy who's missing out on food and shelter because of his tax rate, rather than the guy who has to downgrade his foreign holiday because of his tax rate.

The guy who cant afford shelter is being penalised due to the absence of a property tax on all assets - not because of the absence of progressive tax rates.

It's clearly both - in your regime he is paying 30% rather than ~15% in NZ and ~5% in the UK which has a tax free allowance.

As it stands we have a comprehensive tax, everyone pays. If we push past 15% the need to compensate lower income earners just creates a bigger distortion eroding it's comprehensive nature by stealth. We already have WFF and AS distorting the economy and tax system enormously .

And surely above 15% compliance becomes a exponentially bigger issue.

Tobin tax for the win.

Jeepers... Anything to avoid taxing the rampant engine of inflation called housing.

As the boomer wave crushes NZ, are we heading to see 50% gst and 60% income tax to keep the sacred cow of housing untouched. There would be no one left in NZ to pay tax.

And then what...

Perhaps the effects of a GST of 22% could be mitigated by a universal basic income to help pay for the basics of food and electricity. Targeted benefits have a tendency to create winners and losers.

Sounds like a money go around with a extra govt syphon on the side. No thanks.

We've heard your speel before on this

I do not get the push to exempt the family home. Is it just to make the policy popular enough to get it over the line? I believe all income should be taxed and I also believe tax policy should be as simple as possible. If we exempt the family home I can just see that as another way wealthy people use to avoid paying the tax. Just designate each property the family home before selling, bingo tax free capital gain.

It might make sense if it was part of a coordinated fiscal policy, but given the ad-hoc, siloed way we deal with the fiscal effects of government, the likelihood of that looks pretty slim.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.